Call our 24 hours, seven days a week helpline at 800.272.3900

- Professionals

- Younger/Early-Onset Alzheimer's

- Is Alzheimer's Genetic?

- Women and Alzheimer's

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

- Dementia with Lewy Bodies

- Down Syndrome & Alzheimer's

- Frontotemporal Dementia

- Huntington's Disease

- Mixed Dementia

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Parkinson's Disease Dementia

- Vascular Dementia

- Korsakoff Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Know the 10 Signs

- Difference Between Alzheimer's & Dementia

- 10 Steps to Approach Memory Concerns in Others

- Medical Tests for Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Why Get Checked?

- Visiting Your Doctor

- Life After Diagnosis

- Stages of Alzheimer's

- Earlier Diagnosis

- Part the Cloud

- Research Momentum

- Our Commitment to Research

- TrialMatch: Find a Clinical Trial

- What Are Clinical Trials?

- How Clinical Trials Work

- When Clinical Trials End

- Why Participate?

- Talk to Your Doctor

- Clinical Trials: Myths vs. Facts

- Can Alzheimer's Disease Be Prevented?

- Brain Donation

- Navigating Treatment Options

- Lecanemab Approved for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease

- Aducanumab Discontinued as Alzheimer's Treatment

- Medicare Treatment Coverage

- Donanemab for Treatment of Early Alzheimer's Disease — News Pending FDA Review

- Questions for Your Doctor

- Medications for Memory, Cognition and Dementia-Related Behaviors

- Treatments for Behavior

- Treatments for Sleep Changes

- Alternative Treatments

- Facts and Figures

- Assessing Symptoms and Seeking Help

- Now is the Best Time to Talk about Alzheimer's Together

- Get Educated

- Just Diagnosed

- Sharing Your Diagnosis

- Changes in Relationships

- If You Live Alone

- Treatments and Research

- Legal Planning

- Financial Planning

- Building a Care Team

- End-of-Life Planning

- Programs and Support

- Overcoming Stigma

- Younger-Onset Alzheimer's

- Taking Care of Yourself

- Reducing Stress

- Tips for Daily Life

- Helping Family and Friends

- Leaving Your Legacy

- Live Well Online Resources

- Make a Difference

- Daily Care Plan

- Communication and Alzheimer's

- Food and Eating

- Art and Music

- Incontinence

- Dressing and Grooming

- Dental Care

- Working With the Doctor

- Medication Safety

- Accepting the Diagnosis

- Early-Stage Caregiving

- Middle-Stage Caregiving

- Late-Stage Caregiving

- Aggression and Anger

- Anxiety and Agitation

- Hallucinations

- Memory Loss and Confusion

- Sleep Issues and Sundowning

- Suspicions and Delusions

- In-Home Care

- Adult Day Centers

- Long-Term Care

- Respite Care

- Hospice Care

- Choosing Care Providers

- Finding a Memory Care-Certified Nursing Home or Assisted Living Community

- Changing Care Providers

- Working with Care Providers

- Creating Your Care Team

- Long-Distance Caregiving

- Community Resource Finder

- Be a Healthy Caregiver

- Caregiver Stress

- Caregiver Stress Check

- Caregiver Depression

- Changes to Your Relationship

- Grief and Loss as Alzheimer's Progresses

- Home Safety

- Dementia and Driving

- Technology 101

- Preparing for Emergencies

- Managing Money Online Program

- Planning for Care Costs

- Paying for Care

- Health Care Appeals for People with Alzheimer's and Other Dementias

- Social Security Disability

- Medicare Part D Benefits

- Tax Deductions and Credits

- Planning Ahead for Legal Matters

- Legal Documents

- ALZ Talks Virtual Events

- ALZNavigator™

- Veterans and Dementia

- The Knight Family Dementia Care Coordination Initiative

- Online Tools

- Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Alzheimer's

- Native Americans and Alzheimer's

- Black Americans and Alzheimer's

- Hispanic Americans and Alzheimer's

- LGBTQ+ Community Resources for Dementia

- Educational Programs and Dementia Care Resources

- Brain Facts

- 50 Activities

- For Parents and Teachers

- Resolving Family Conflicts

- Holiday Gift Guide for Caregivers and People Living with Dementia

- Trajectory Report

- Resource Lists

- Search Databases

- Publications

- Favorite Links

- 10 Healthy Habits for Your Brain

- Stay Physically Active

- Adopt a Healthy Diet

- Stay Mentally and Socially Active

- Online Community

- Support Groups

Find Your Local Chapter

- Any Given Moment

- New IDEAS Study

- RFI Amyloid PET Depletion Following Treatment

- Bruce T. Lamb, Ph.D., Chair

- Christopher van Dyck, M.D.

- Cynthia Lemere, Ph.D.

- David Knopman, M.D.

- Lee A. Jennings, M.D. MSHS

- Karen Bell, M.D.

- Lea Grinberg, M.D., Ph.D.

- Malú Tansey, Ph.D.

- Mary Sano, Ph.D.

- Oscar Lopez, M.D.

- Suzanne Craft, Ph.D.

- About Our Grants

- Andrew Kiselica, Ph.D., ABPP-CN

- Arjun Masurkar, M.D., Ph.D.

- Benjamin Combs, Ph.D.

- Charles DeCarli, M.D.

- Damian Holsinger, Ph.D.

- David Soleimani-Meigooni, Ph.D.

- Donna M. Wilcock, Ph.D.

- Elizabeth Head, M.A, Ph.D.

- Fan Fan, M.D.

- Fayron Epps, Ph.D., R.N.

- Ganesh Babulal, Ph.D., OTD

- Hui Zheng, Ph.D.

- Jason D. Flatt, Ph.D., MPH

- Jennifer Manly, Ph.D.

- Joanna Jankowsky, Ph.D.

- Luis Medina, Ph.D.

- Marcello D’Amelio, Ph.D.

- Marcia N. Gordon, Ph.D.

- Margaret Pericak-Vance, Ph.D.

- María Llorens-Martín, Ph.D.

- Nancy Hodgson, Ph.D.

- Shana D. Stites, Psy.D., M.A., M.S.

- Walter Swardfager, Ph.D.

- ALZ WW-FNFP Grant

- Capacity Building in International Dementia Research Program

- ISTAART IGPCC

- Alzheimer’s Disease Strategic Fund: Endolysosomal Activity in Alzheimer’s (E2A) Grant Program

- Imaging Research in Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Zenith Fellow Awards

- National Academy of Neuropsychology & Alzheimer’s Association Funding Opportunity

- Part the Cloud-Gates Partnership Grant Program: Bioenergetics and Inflammation

- Pilot Awards for Global Brain Health Leaders (Invitation Only)

- Robert W. Katzman, M.D., Clinical Research Training Scholarship

- Funded Studies

- How to Apply

- Portfolio Summaries

- Supporting Research in Health Disparities, Policy and Ethics in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia Research (HPE-ADRD)

- Diagnostic Criteria & Guidelines

- Annual Conference: AAIC

- Professional Society: ISTAART

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: DADM

- Alzheimer's & Dementia: TRCI

- International Network to Study SARS-CoV-2 Impact on Behavior and Cognition

- Alzheimer’s Association Business Consortium (AABC)

- Global Biomarker Standardization Consortium (GBSC)

- Global Alzheimer’s Association Interactive Network

- International Alzheimer's Disease Research Portfolio

- Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Private Partner Scientific Board (ADNI-PPSB)

- Research Roundtable

- About WW-ADNI

- North American ADNI

- European ADNI

- Australia ADNI

- Taiwan ADNI

- Argentina ADNI

- WW-ADNI Meetings

- Submit Study

- RFI Inclusive Language Guide

- Scientific Conferences

- AUC for Amyloid and Tau PET Imaging

- Make a Donation

- Walk to End Alzheimer's

- The Longest Day

- RivALZ to End ALZ

- Ride to End ALZ

- Tribute Pages

- Gift Options to Meet Your Goals

- Founders Society

- Fred Bernhardt

- Anjanette Kichline

- Lori A. Jacobson

- Pam and Bill Russell

- Gina Adelman

- Franz and Christa Boetsch

- Adrienne Edelstein

- For Professional Advisors

- Free Planning Guides

- Contact the Planned Giving Staff

- Workplace Giving

- Do Good to End ALZ

- Donate a Vehicle

- Donate Stock

- Donate Cryptocurrency

- Donate Gold & Sterling Silver

- Donor-Advised Funds

- Use of Funds

- Giving Societies

- Why We Advocate

- Ambassador Program

- About the Alzheimer’s Impact Movement

- Research Funding

- Improving Care

- Support for People Living With Dementia

- Public Policy Victories

- Planned Giving

- Community Educator

- Community Representative

- Support Group Facilitator or Mentor

- Faith Outreach Representative

- Early Stage Social Engagement Leaders

- Data Entry Volunteer

- Tech Support Volunteer

- Other Local Opportunities

- Visit the Program Volunteer Community to Learn More

- Become a Corporate Partner

- A Family Affair

- A Message from Elizabeth

- The Belin Family

- The Eliashar Family

- The Fremont Family

- The Freund Family

- Jeff and Randi Gillman

- Harold Matzner

- The Mendelson Family

- Patty and Arthur Newman

- The Ozer Family

- Salon Series

- No Shave November

- Other Philanthropic Activities

- Still Alice

- The Judy Fund E-blast Archive

- The Judy Fund in the News

- The Judy Fund Newsletter Archives

- Sigma Kappa Foundation

- Alpha Delta Kappa

- Parrot Heads in Paradise

- Tau Kappa Epsilon (TKE)

- Sigma Alpha Mu

- Alois Society Member Levels and Benefits

- Alois Society Member Resources

- Zenith Society

- Founder's Society

- Joel Berman

- JR and Emily Paterakis

- Legal Industry Leadership Council

- Accounting Industry Leadership Council

Find Local Resources

Let us connect you to professionals and support options near you. Please select an option below:

Use Current Location Use Map Selector

Search Alzheimer’s Association

- Who's at risk?

Reduce the risk of wandering

Take action when wandering occurs, prepare your home, who's at risk for wandering.

- Returning from a regular walk or drive later than usual.

- Forgetting how to get to familiar places.

- Talking about fulfilling former obligations, such as going to work

- Trying or wanting to “go home” even when at home.

- Becoming restless, pacing or making repetitive movements.

- Having difficulty locating familiar places, such as the bathroom, bedroom or dining room.

- Asking the whereabouts of past friends and family.

- Acting as if doing a hobby or chore, but nothing gets done.

- Appearing lost in a new or changed environment.

- Becoming nervous or anxious in crowded areas, such as markets or restaurants.

- Provide opportunities for the person to engage in structured, meaningful activities throughout the day

- Identify the time of day the person is most likely to wander (for those who experience “ sundowning ,” this may be starting in the early evening.) Plan things to do during this time — activities and exercise may help reduce anxiety, agitation and restlessness.

- Ensure all basic needs are met, including toileting, nutrition and hydration. Consider reducing – but not eliminating – liquids up to two hours before bedtime so the person doesn’t have to use and find the bathroom during the night.

- Involve the person in daily activities, such as folding laundry or preparing dinner. Learn about creating a daily plan .

- Reassure the person if he or she feels lost, abandoned or disoriented.

- If the person is still safely able to drive, consider using a GPS device to help if they get lost.

- If the person is no longer driving, remove access to car keys — a person living with dementia may not just wander by foot. The person may forget that he or she can no longer drive.

- Avoid busy places that are confusing and can cause disorientation, such as shopping malls.

- Assess the person’s response to new surroundings. Do not leave someone with dementia unsupervised if new surroundings may cause confusion, disorientation or agitation.

- Decide on a set time each day to check in with each other.

- Review scheduled activities and appointments for the day together.

- If the care partner is not available, identify a companion for the person living with dementia as needed.

- Consider alternative transportation options if getting lost or driving safely becomes a concern.

As the disease progresses and the risk for wandering increases, assess your individual situation to see which of the safety measures below may work best to help prevent wandering.

Home Safety Checklist

Download, print and keep the checklist handy to prevent dangerous situations and help maximize the person living with dementia’s independence for as long as possible.

- Place deadbolts out of the line of sight, either high or low, on exterior doors. (Do not leave a person living with dementia unsupervised in new or changed surroundings, and never lock a person in at home.)

- Use night lights throughout the home.

- Cover door knobs with cloth the same color as the door or use safety covers.

- Camouflage doors by painting them the same color as the walls or covering them with removable curtains or screens.

- Use black tape or paint to create a two-foot black threshold in front of the door. It may act as a visual stop barrier.

- Install warning bells above doors or use a monitoring device that signals when a door is opened.

- Place a pressure-sensitive mat in front of the door or at the person's bedside to alert you to movement.

- Put hedges or a fence around the patio, yard or other outside common areas.

- Use safety gates or brightly colored netting to prevent access to stairs or the outdoors.

- Monitor noise levels to help reduce excessive stimulation.

- Create indoor and outdoor common areas that can be safely explored.

- Label all doors with signs or symbols to explain the purpose of each room.

- Store items that may trigger a person’s instinct to leave, such as coats, hats, pocketbooks, keys and wallets.

- Do not leave the person alone in a car.

- Consider enrolling the person living with dementia in a wandering response service.

- Ask neighbors, friends and family to call if they see the person wandering, lost or dressed inappropriately.

- Keep a recent, close-up photo of the person on hand to give to police, should the need arise.

- Know the person’s neighborhood. Identify potentially dangerous areas near the home, such as bodies of water, open stairwells, dense foliage, tunnels, bus stops and roads with heavy traffic.

- Create a list of places the person might wander to, such as past jobs, former homes, places of worship or a favorite restaurant.

When someone with dementia is missing

Begin search-and-rescue efforts immediately. Many individuals who wander are found within 1.5 miles of where they disappeared.

- Start search efforts immediately. When looking, consider whether the individual is right- or left-handed — wandering patterns generally follow the direction of the dominant hand.

- Begin by looking in the surrounding vicinity — many individuals who wander are found within 1.5 miles of where they disappeared.

- Check local landscapes, such as ponds, tree lines or fence lines — many individuals are found within brush or brier.

- If applicable, search areas the person has wandered to in the past.

- If the person is not found within 15 minutes, call 911 to file a missing person’s report. Inform the authorities that the person has dementia.

Other pages in Stages and Behaviors

- Care Options

- Caregiver Health

- Financial and Legal Planning for Caregivers

Related Pages

Connect with our free, online caregiver community..

Join ALZConnected

Our blog is a place to continue the conversation about Alzheimer's.

Read the Blog

The Alzheimer’s Association is in your community.

Keep up with alzheimer’s news and events.

- Alzheimer's & Dementia

- Asthma & Allergies

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Breast Cancer

- Cardiovascular Health

- Environment & Sustainability

- Exercise & Fitness

- Headache & Migraine

- Health Equity

- HIV & AIDS

- Human Biology

- Men's Health

- Mental Health

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Parkinson's Disease

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Sexual Health

- Ulcerative Colitis

- Women's Health

- Nutrition & Fitness

- Vitamins & Supplements

- At-Home Testing

- Men’s Health

- Women’s Health

- Latest News

- Medical Myths

- Honest Nutrition

- Through My Eyes

- New Normal Health

- 2023 in medicine

- Why exercise is key to living a long and healthy life

- What do we know about the gut microbiome in IBD?

- My podcast changed me

- Can 'biological race' explain disparities in health?

- Why Parkinson's research is zooming in on the gut

- Health Hubs

- Find a Doctor

- BMI Calculators and Charts

- Blood Pressure Chart: Ranges and Guide

- Breast Cancer: Self-Examination Guide

- Sleep Calculator

- RA Myths vs Facts

- Type 2 Diabetes: Managing Blood Sugar

- Ankylosing Spondylitis Pain: Fact or Fiction

- Our Editorial Process

- Content Integrity

- Conscious Language

- Health Conditions

- Health Products

What to know about dementia wandering

Some people with dementia may wander away from their homes or caregivers if they experience confusion about where they are.

Dementia refers to symptoms affecting memory, communication, and cognition that result from underlying conditions and brain disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

This article explores who is at risk of wandering with dementia, the stage at which this behavior may occur, and the causes of wandering. It also looks at ways to reduce the risk of wandering and steps to take when wandering occurs.

Information for caregivers

As a person’s condition progresses, they may need help reading or understanding information regarding their circumstances. This article contains details that may help caregivers identify and monitor symptom progression, side effects of drugs, or other factors relating to the person’s condition.

Who is at risk of wandering?

A 2021 article relates wandering to “aimless locomotion behavior” and states that it is common.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association , all people living with Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia are at risk of wandering. This is because Alzheimer’s disease causes people to lose the ability to recognize familiar settings and people.

Wandering can be dangerous, and the risks it poses can prove stressful for caregivers and loved ones.

Signs of increased risk

A person may be at risk of wandering if they begin:

- returning later than usual from a regular walk or drive

- forgetting directions to familiar places inside and outside the house

- talking about fulfilling former obligations, such as going to work after retiring

- trying to go home even when at home

- becoming restless and pacing

- making repetitive movements

- asking the whereabouts of deceased friends and family

- appearing lost in new environments

- becoming nervous in busy places

Read more about other behavioral changes associated with dementia .

When does wandering occur?

The Alzheimer’s Association suggests 60% of people with dementia will experience wandering at least once. Some may do it repeatedly.

It notes that wandering can occur at any stage of dementia, but the risk may increase as symptoms progress.

It may be best for family or caregivers to speak with a doctor if they notice signs that a person may be at risk of wandering or if the behavior occurs.

People can seek support from organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association. It organizes support groups that offer a safe place for caregivers and loved ones of people with dementia to meet and share their experiences.

Find out more about the stages of dementia .

Why might people with dementia wander?

Researchers still do not know the exact cause of wandering with dementia, but they link it to the severity of cognitive impairment, including issues with:

- recent and remote memory

- time and place orientation

- the ability to react appropriately to a given conversation subject

They note that people with Lewy body dementia are more likely than those with vascular dementia to wander.

People with dementia who are receiving antipsychotic treatment , have comorbid conditions, or display behaviors such as arguing and threatening may also be more likely to wander. These conditions include depression and psychosis .

Potential causes

According to researchers, wandering behavior may have a neurophysical explanation that relates to the following:

- visuospatial dysfunction , which affects a person’s spatial awareness or ability to judge distances

- visuoconstructional impairment , which reduces the ability to accurately copy or draw objects, recognize shapes and patterns, and complete visual puzzles

- reduced topographical memory , which affects a person’s ability to locate where they are

They suggest it may also be an attempt to fulfill physiological or psychological needs, such as a response to stress, trauma, or loneliness.

Alternatively, it may be due to unfamiliarity with the environment, changes to medications or schedules, or a severe decline in cognitive function.

The United Kingdom’s Alzheimer’s Society provides further potential reasons for wandering, such as:

- memory loss

- confusion about the time at which the person usually performs activities

- pain or distress

- anxiety or agitatation

- a lack of physical activity

- continuing a previous habit

- searching for someone in the past

- feeling lost

How to reduce the risk of wandering

Caregivers or family members may be able to reduce the risk of wandering. However, they may not be able to guarantee that a person living with dementia will not wander.

The following strategies may help:

- providing opportunities for structured and engaging activities throughout the day

- identifying the time of the day when a person is likely to wander, such as the “ sundowner’s period ” as night approaches, and planning activities during this time

- ensuring the person’s needs for food, drink, and use of the bathroom are met

- involving the person in daily activities, such as folding laundry or preparing dinner

- providing reassurance when the person is lost, anxious, or disoriented

- using a GPS device if it is safe for the person to go out walking or driving

- avoiding busy places that may be stressful, such as shopping malls

- assessing the person’s reactions and feelings toward new environments

In the early stages

The Alzheimer’s Association suggests individuals with early stage dementia may benefit from engaging in the following with family or caregivers:

- deciding on a set time each day to check in with each other

- reviewing schedules and appointments together

- identifying companions who can support the person when others are not available

- considering transportation to avoid wandering

Learn more about early stage dementia .

Preparing the home

The National Institute of Aging suggests the following may help prevent a person with dementia from wandering away from home:

- keeping doors locked

- using loosely fitting doorknob covers

- removable gates

- installing devices on windows to limit how much they can open

- installing bells, alarms, or pressure-sensitive mats when the door opens

- securing outside areas with fencing and a locked gate

- keeping keys, shoes, suitcases, and other items that may trigger the instinct to leave out of sight

Safety measures

If the risk of wandering increases, the following safety measures may help :

- placing deadbolts on the door, out of sight, but only locking them when someone is in the house with the person

- camouflaging doors with the same colors as the walls

- supervising the person when they are in new or changed surroundings or a car

- creating a threshold in front of the door with paint or tape to create a visual barrier

- using night lights and safety gates

- monitoring noise levels to reduce excessive stimulation

- creating safe spaces to explore inside or outside the house

- labeling rooms with signs to explain their purpose

Alzheimer’s Association support groups may provide additional support and resources for caregivers of a person with dementia.

Read more about caring for someone with dementia .

Planning ahead

Families and caregivers may also benefit from having a plan in place in case of an emergency. This may involve:

- enrolling the person living with dementia in a wandering response service

- asking neighbors or other people to call if they see a person wandering

- keeping recent photos of the person to give to police in case of emergency

- getting to know the person’s neighborhood well and identifying potential hazards

- creating a list of places the person may wander to

The National Institute of Aging suggests it may also help to:

- make sure the person carries identification or wears a medical bracelet to let people know about their dementia

- sew labels on the person’s clothing to aid identification

- keep an item of the person’s worn, unwashed clothing in a plastic bag to aid in finding them with the use of dogs, if necessary

People can reach out to support groups and various organizations for additional advice.

Find out more about dementia support groups .

Taking action when wandering occurs

If a person with dementia wanders away from home, people can act immediately by taking the following steps :

- Start search efforts immediately and consider looking in the direction that relates to the missing person’s dominant writing hand first.

- Search the surrounding area and places where a person has wandered in the past, if applicable.

- Check local landscapes, such as ponds, tree lines, or fence lines.

- Call 911 if they do not find the person within 15 minutes and inform any other relevant local authorities.

People at any stage of dementia are at risk of wandering. Family and caregivers can look for signs a person may be at risk of wandering, such as forgetting directions, asking about deceased family members, or making repetitive movements.

Protecting a person from wandering may involve keeping the home as secure as possible and storing items that may trigger the instinct to leave the house out of sight.

Family or caregivers can also implement plans that allow them to act immediately in an emergency. For example, they may enroll the person in a wandering response service and create a list of places they may wander to. People should call 911 if they do not find a person with dementia who has wandered away from home within 15 minutes.

Last medically reviewed on December 14, 2023

- Alzheimer's / Dementia

How we reviewed this article:

- Agrawal AK, et al. (2021). Approach to management of wandering in dementia: Ethical and legal issue. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8543604/

- How can dementia change a person's perception? (2022). https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/how-dementia-changes-perception

- Lim TS, et al. (2010). Topographical disorientation in mild cognitive impairment: A voxel-based morphometry study. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3024525/

- Simons R. (2023). Exploring visuoconstructional impairment in dementia syndromes? https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/exploring-visuoconstructional-impairment-in-dementia-syndromes-125676.html

- Support groups. (n.d.). https://www.alz.org/alzwa/helping_you/support_groups

- Wandering and Alzheimer's disease. (2017). https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/wandering-and-alzheimers-disease

- Wandering and dementia. (n.d.). https://alzheimer.ca/bc/en/help-support/programs-services/dementia-resources-bc/wandering-disorientation-resources/wandering-dementia

- Wandering and getting lost: Who’s at risk and how to be prepared. (2023). https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-dementia-wandering-behavior-ts.pdf

- Wandering. (n.d.). https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering

- Why a person with dementia might be walking about. (2021). https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-dementia/symptoms-and-diagnosis/why-person-with-dementia-might-be-walking-about

Share this article

Latest news

- Microplastics found in food and water may spread from the gut to the brain

- Could HIV drugs help keep Alzheimer’s at bay?

- New guidelines recommend GLP-1 drugs such as Ozempic to help treat type 2 diabetes in adults

- Calorie counting as effective for weight loss as time-restricted eating, new study finds

- Mediterranean diet tied to lower hypertension risk, 20 years' worth of data show

Related Coverage

Some forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease and Lewy body dementia, may have a genetic component. Single genes may cause the condition in some…

Treatment for dementia agitation may include medications and creating a supportive, comforting environment.

It can be difficult to know how to talk with someone with dementia. Learn more about different communication techniques and how to get started.

Jobs that do not require as much mental engagement as other types of work are associated with higher rates of cognitive impairment after age 70…

Researchers are reporting additional health risks associated with prescribing antipsychotic medications to people with dementia

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Sundowning: late-day confusion, i've heard that sundowning may happen with dementia. what is sundowning and how is it treated.

The term "sundowning" refers to a state of confusion that occurs in the late afternoon and lasts into the night. Sundowning can cause various behaviors, such as confusion, anxiety, aggression or ignoring directions. Sundowning also can lead to pacing or wandering.

Sundowning isn't a disease. It's a group of symptoms that occurs at a specific time of the day. These symptoms may affect people with Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia. The exact cause of sundowning is not known.

Factors that may worsen late-day confusion

- Spending a day in a place that's not familiar.

- Low lighting.

- Increased shadows.

- Disruption of the body's "internal clock."

- Trouble separating reality from dreams.

- Being hungry or thirsty.

- Presence of an infection, such as a urinary tract infection.

- Being bored or in pain.

- Depression.

Tips for reducing sundowning

- Keep a predictable routine for bedtime, waking, meals and activities.

- Plan for activities and exposure to light during the day to support nighttime sleepiness.

- Limit daytime napping.

- Limit caffeine and sugar to morning hours.

- Turn on a night light to reduce agitation that occurs when surroundings are dark or not familiar.

- In the evening, try to reduce background noise and stimulating activities. This includes TV viewing, which can sometimes be upsetting.

- In a strange or not familiar setting, bring familiar items, such as photographs. They can create a more relaxed setting.

- In the evening, play familiar, gentle music or relaxing sounds of nature, such as the sound of waves.

Some research suggests that a low dose of melatonin may help ease sundowning. Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone that induces sleepiness. It can help when taken alone or in combination with exposure to bright light during the day.

It's possible that a medicine side effect, pain, depression or other condition could contribute to sundowning. Talk with a healthcare professional if you suspect that a condition might be making someone's sundowning worse. A urinary tract infection or sleep apnea could be contributing to sundowning, especially if it comes on quickly.

Jonathan Graff-Radford, M.D.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Alzheimer's prevention: Does it exist?

- Todd WD. Potential pathways for circadian dysfunction and sundowning-related behavioral aggression in Alzheimer's disease and related dementia. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2020; doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00910.

- Sleep issues and sundowning. Alzheimer's Association. http://www.alz.org/care/alzheimers-dementia-sleep-issues-sundowning.asp. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Managing personality and behavior changes in Alzheimer's. National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/managing-personality-and-behavior-changes-alzheimers. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Francis J. Delirium and confusional states: Prevention, treatment, and prognosis. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Graff-Radford J (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. April 7, 2022.

- Tips for coping with sundowning. National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/tips-coping-sundowning. Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Reiter RJ, et al. Brain washing and neural health: Role of age, sleep and the cerebrospinal fluid melatonin rhythm. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2023; doi:10.1007/s00018-023-04736-5.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Alzheimer's Disease

- Assortment of Products for Independent Living from Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Day to Day: Living With Dementia

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Healthy Aging

- Give today to find Alzheimer's cures for tomorrow

- Alzheimer's sleep problems

- Alzheimer's: New treatments

- Alzheimer's 101

- Understanding the difference between dementia types

- Alzheimer's disease

- Alzheimer's genes

- Alzheimer's drugs

- Alzheimer's stages

- Antidepressant withdrawal: Is there such a thing?

- Antidepressants and alcohol: What's the concern?

- Antidepressants and weight gain: What causes it?

- Antidepressants: Can they stop working?

- Antidepressants: Side effects

- Antidepressants: Selecting one that's right for you

- Antidepressants: Which cause the fewest sexual side effects?

- Anxiety disorders

- Atypical antidepressants

- Caregiver stress

- Clinical depression: What does that mean?

- Corticobasal degeneration (corticobasal syndrome)

- Depression and anxiety: Can I have both?

- Depression, anxiety and exercise

- What is depression? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

- Depression in women: Understanding the gender gap

- Depression (major depressive disorder)

- Depression: Supporting a family member or friend

- Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Did the definition of Alzheimer's disease change?

- How your brain works

- Intermittent fasting

- Lecanemab for Alzheimer's disease

- Male depression: Understanding the issues

- MAOIs and diet: Is it necessary to restrict tyramine?

- Marijuana and depression

- Mayo Clinic Minute: 3 tips to reduce your risk of Alzheimer's disease

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Alzheimer's disease risk and lifestyle

- Mayo Clinic Minute: New definition of Alzheimer's changes

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Women and Alzheimer's Disease

- Memory loss: When to seek help

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- Natural remedies for depression: Are they effective?

- Nervous breakdown: What does it mean?

- New Alzheimers Research

- Pain and depression: Is there a link?

- Phantosmia: What causes olfactory hallucinations?

- Positron emission tomography scan

- Posterior cortical atrophy

- Seeing inside the heart with MRI

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Treatment-resistant depression

- Tricyclic antidepressants and tetracyclic antidepressants

- Video: Alzheimer's drug shows early promise

- Vitamin B-12 and depression

- Young-onset Alzheimer's

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Sundowning Late-day confusion

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Diseases & Diagnoses

Issue Index

- Case Reports

Cover Focus | June 2022

Wandering & Sundowning in Dementia

Preventive and acute management of some of the most challenging aspects of dementia is possible..

Taylor Thomas, BA; and Aaron Ritter, MD

Alzheimer disease (AD) and related dementias are complex disorders that affect multiple brain systems, resulting in a wide range of cognitive and behavioral manifestations. The behavioral symptoms often have clinical analogs in idiopathic psychiatric disorders and are frequently referred to as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) of dementia. Many therapeutic strategies for NPS are borrowed from treatment of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) commonly used to treat major depressive disorder may also be prescribed for depressive symptoms in AD. This strategy has been deemed the “therapeutic metaphor” and has shown varying degrees of success in clinical trials. 1

Clinicians face significant challenges, however, when there is no suitable metaphor to guide treatment for behaviors that emerge solely in dementia. This is particularly problematic for 2 of the most burdensome behavioral manifestations of dementia—sundowning (the worsening of symptoms in the late afternoon and early evening) and wandering. Despite being among the most impactful behaviors in dementia, there is very little research evidence to guide therapeutic approaches. This review provides a brief update of the current literature regarding wandering and sundowning in dementia. Using evidence-based approaches from the research literature, where available, and best practices adopted from our own clinical practice when little evidence exists, we outline a practical treatment algorithm that can be used in the clinic when facing either of these common and problematic behaviors.

Wandering Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Wandering is a complex behavioral phenomenon that is frequent in dementia. Approximately 20% of community-dwelling individuals with dementia and 60% of those living in institutionalized settings are reported to wander .2 Most definitions of wandering incorporate a variety of dementia-related locomotion activities, including elopement (ie, attempts to escape), repetitive pacing, and becoming lost. 3 More recently, the term “critical wandering” or “missing incidents” have been used to draw distinctions between elopement and pacing vs wandering and becoming lost. 4 Critical wandering episodes have a high mortality rate of 20%, placing this symptom among the most dangerous behavioral manifestations of dementia. 5

The risk of wandering increases with severity of cognitive impairment, with the highest rate in those with Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores of 13 or less. 6 Individuals who frequently wander (ie, multiple times per week) almost always have at least moderate dementia. Few studies have compared wandering rates among people with different types of dementia. 7 Experience from our clinical practice suggests that wandering is most common in AD—where spatial disorientation and amnesia are common clinical features—but can also occur in moderate to advanced stages of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Lewy body dementia (LBD). The presence of comorbid NPS (eg, severe depression, sleep disorders, and psychosis) may increase the likelihood of wandering. 8

Causes of wandering are not well understood. Some hypothesize wandering emerges from disconnection among brain regions responsible for visuospatial, motor, and memory functions. A positron-emission tomography (PET) study of 342 individuals with AD, 80 of whom were considered wanderers, found a distinct pattern of hypometabolism in the cingulum and supplementary motor areas among wanderers. Correlations between specific brain regions and the type of wandering (eg, pacing, lapping, or random) were also seen. 9

A relatively larger body of research informs psychosocial perspectives on wandering with 3 scenarios identified in which wandering behaviors commonly emerge, including 1) escape from an unfamiliar setting; 2) desire for social interaction; and 3) exercise behavior triggered by restlessness or lack of activity. Other factors that increase wandering behavior include lifelong low ability to tolerate stress, an individual’s belief that they are still employed at a job, and a repeated desire to search for people (eg, dead family members) or places (eg, a home where they no longer reside). 10

Managing Wandering

There is little empiric evidence to inform treatment approaches to wandering in dementia. Nonpharmaceutical interventions that promote “safe walking” instead of aimless wandering are preferred initial approaches. Several “low tech” options with low associated costs and negligible side effects have some evidence for use, including exercise programs, aromatherapy, placing murals and other paintings in front of exit doors, or hiding door handles. 11 More recently, the explosion of discrete and affordable wearable devices that have global positioning system (GPS) tracking ability have significantly expanded the number of “high-tech” options available to address elopement. These include GPS tagging, bed and door alarms, and surveillance systems. Few have been tested in prospective, placebo-controlled studies, however, making it hard to make firm conclusions regarding efficacy. 12 The ethical implications of using these technologies—including potential infringements on privacy, dignity, and autonomy of individuals—are seldom considered in clinical trials or clinical practice. 13

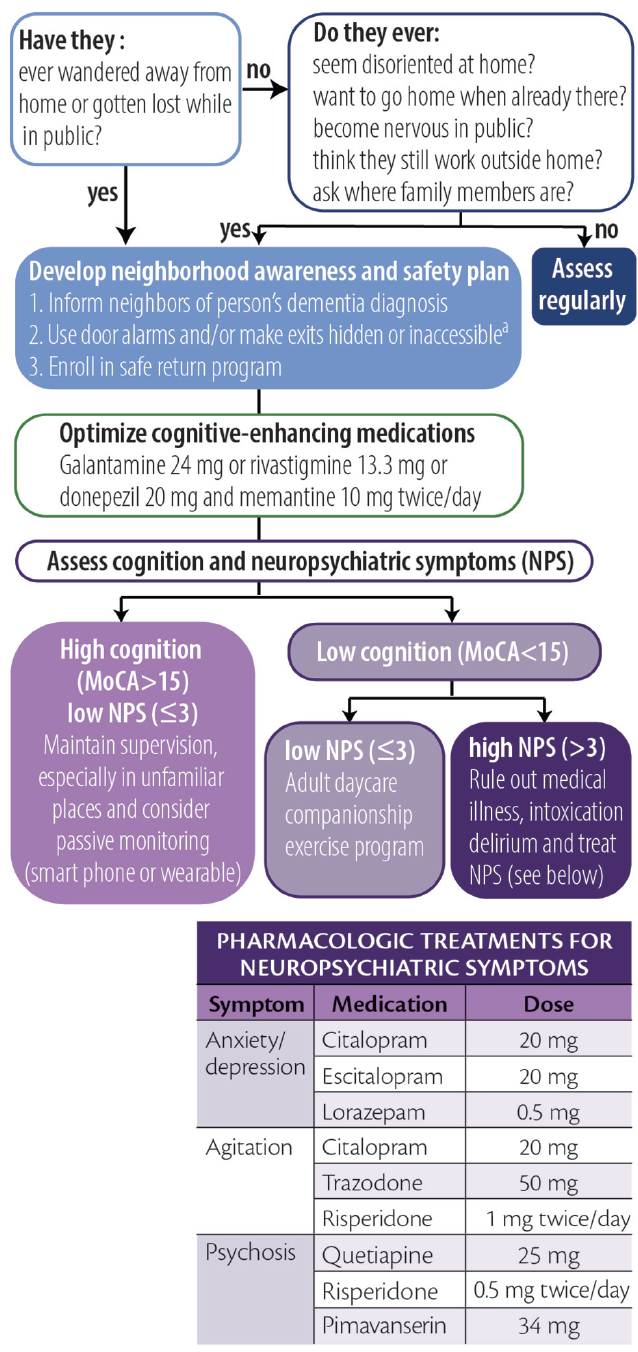

Considering the high prevalence and often deadly consequences associated with wandering, we offer a practical, algorithmic approach to wandering in dementia (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Algorithmic approach to wandering. Abbreviation: MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment. a Persons with dementia should never be left alone behind locked doors.

Click to view larger

Screening for Wandering

To screen for wandering behavior, we ask the following 2 questions of or about all persons with dementia:

1. Have they ever wandered away from their home?

2. Have they ever gotten lost while in public?

If either of these are responded to affirmatively, we make recommendations and stratify risk as described below. If both questions are responded to with “no,” we ask if they:

1. ever seem disoriented at home or in familiar places?

2. ever report a desire to go home even while at home?

3. become excessively nervous while in public?

4. talk about needing to fulfill prior work obligations?

5. ask about the whereabouts of past family or friends?

An affirmative answer to any of these 5 questions may indicate an increased risk for wandering. For those who wander or are at high risk for wandering we provide basic education, recommend increased diligence, and maximize behavioral strategies to improve orientation (eg, display a written calendar and/or a large digital clock with time and date and optimize use of cognitive-enhancing agents when appropriate).

Creating a Wandering Safety Plan

Once a wandering event has occurred, we recommend families develop a neighborhood awareness and safety plan. The Alzheimer’s Association’s website has excellent resources devoted toward developing this plan ( https://www.alz.org/help-support/caregiving/stages-behaviors/wandering ). At a minimum, the safety plan should include notifying neighbors that the person has dementia, keeping a list of places they are likely to wander to, and having a recent photo readily available for emergency medical and other services. We also educate families about the initial steps to take if wandering occurs, including immediately searching areas favoring the direction of the dominant hand, focusing the search within 1.5 miles of the home, and calling 9-1-1 no more than 15 minutes after a person with dementia has been determined to be missing. Additional recommendations include obtaining medical identification jewelry, installing door alarms, and making locks inaccessible (ie, hiding them or placing them out of reach). Families should be encouraged to enroll in a safe return program (eg, MedicAlert, Project Lifesaver, or Silver Alert) if one is available in their area. It is important to note that people with dementia should never be locked by themselves inside a home.

Managing Risk by Stratified Wandering Type

Cluster analyses show people who wander can largely be grouped into 1 of 3 different types based on cognitive and behavioral characteristics. 14 These groupings are useful for tailoring interventions and can be identified for an individual with combined cognitive test scores and behavioral symptom profiles. We use the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) 15 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q) 16 because they are relatively quick to administer while providing important information and can be simultaneously administered to caregivers (NPI-Q) and patients (MoCA). These assessments can be used to stratify patients as follows.

Group 1: High Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Individuals who score greater than 15 on the MoCA and have 3 or fewer behavioral symptoms wander infrequently (<1 time/month) and often only in unfamiliar settings. Because wandering is usually triggered by unexpected stressors, the main goal for these individuals is to provide adequate supervision in unfamiliar settings. Those in this group may also still carry a mobile phone with several high-tech options (eg, GPS systems or “find my phone” apps) that may be beneficial.

Group 2: Low Cognitive Function, Low Behavioral Disturbances. Persons with lower cognitive test scores (eg, ≤10 on the MoCA) and fewer than 3 NPS may wander because of boredom or a lack of physical or cognitive stimulation. For this group, we recommend a companion caregiver or adult daycare program to engage the patient in enjoyable activities and incorporate supervised walks or exercise programs during the day. Individuals in this group may benefit from the creation of an outdoor area that may be explored safely.

Group 3: Low Cognitive Function, High Behavioral Disturbances. People in this group require the most proactive approaches because they are likely to be the most frequent wanderers and may be at highest risk for dangerous outcomes. Wandering in this group may be driven by delusions, particularly the persecutory type. 8 We recommend, as a first step, determining whether other factors such as pain, delirium, or intoxication may be contributing to the person’s NPS. If no additional etiologies can be clearly identified, comorbid NPS should be addressed with best clinical practices, borrowing heavily from psychiatry with the “therapeutic metaphor” (See Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia in this issue). Many in this group may require institutionalization or constant supervision from hired caregivers to prevent harm. Nonpharmacologic strategies recommended for this group include taping a 2-foot black threshold in front of each door to serve as a visual barrier, installing cameras and warning alarms for outward facing doors, and installing safety gates around the house.

Sundowning Frequency, Consequences & Causes

Sundowning is the term used to describe the emergence or intensification of NPS occurring in the early evening. This phenomenon, thought to be unique to people with dementia, has long been recognized by researchers and caregivers as being among the most challenging elements of dementia care. 17 Although most frequently seen in AD, sundowning has also frequently been observed in other forms of dementia. Sundowning is among the most common behavioral manifestations of dementia, with rates in institutionalized settings exceeding 80%. 18 The risk of sundowning increases in moderate and severe dementia and because of its close association with sunlight, is more common in the autumn and winter seasons. 19

The impact of sundowning on persons with dementia is immense. Sundowning is among the most common reasons for institutionalization and is associated with faster rates of cognitive decline and increased risk for wandering. 17 Sundowning also increases care partner stress, which, in turn, may increase risk for agitation in patients. 18

The causes of sundowning are likely multifactorial. Sundowning is commonly linked to alterations in circadian rhythms. 19 Autopsy studies of people who had AD show a disproportionate loss of neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which regulates the release of melatonin in response to light. 20 Other research links sundowning to reductions in cholinergic neurotransmission, 21 and at least 1 study showed increased levels of cortisol, which may suggest alterations of the entire hypothalamic-pituitary axis. 21 Sleep disruption, inadequate sunlight exposure, and disrupted routines increase the likelihood of sundowning. 17 Medications with anticholinergic properties and sedatives may also exacerbate sundowning.

Management of Sundowning

The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model provides a framework for understanding and managing sundowning. 22 In this model, sundowning occurs because diurnal alterations in circadian rhythms temporally correlate with increases in pain, hunger, or fatigue that occur later in the day. Disruptions in emotional regulation emerge when a person’s ability to tolerate such stressors is exceeded.

As with wandering, there is little empiric evidence to guide pharmacologic management of sundowning. Melatonin has been studied in several open-label studies and case series with varying levels of success. 23 Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine reduce agitated behaviors, but have not been studied for management of sundowning. 24 Nonpharmacologic interventions (eg, eliminating daytime naps, increasing sunlight exposure, aerobic exercise, and playing music) can reduce sundowning, 17 but it is difficult to make firm conclusions about the efficacy of these measures because most have not been evaluated in prospective, placebo-controlled studies.

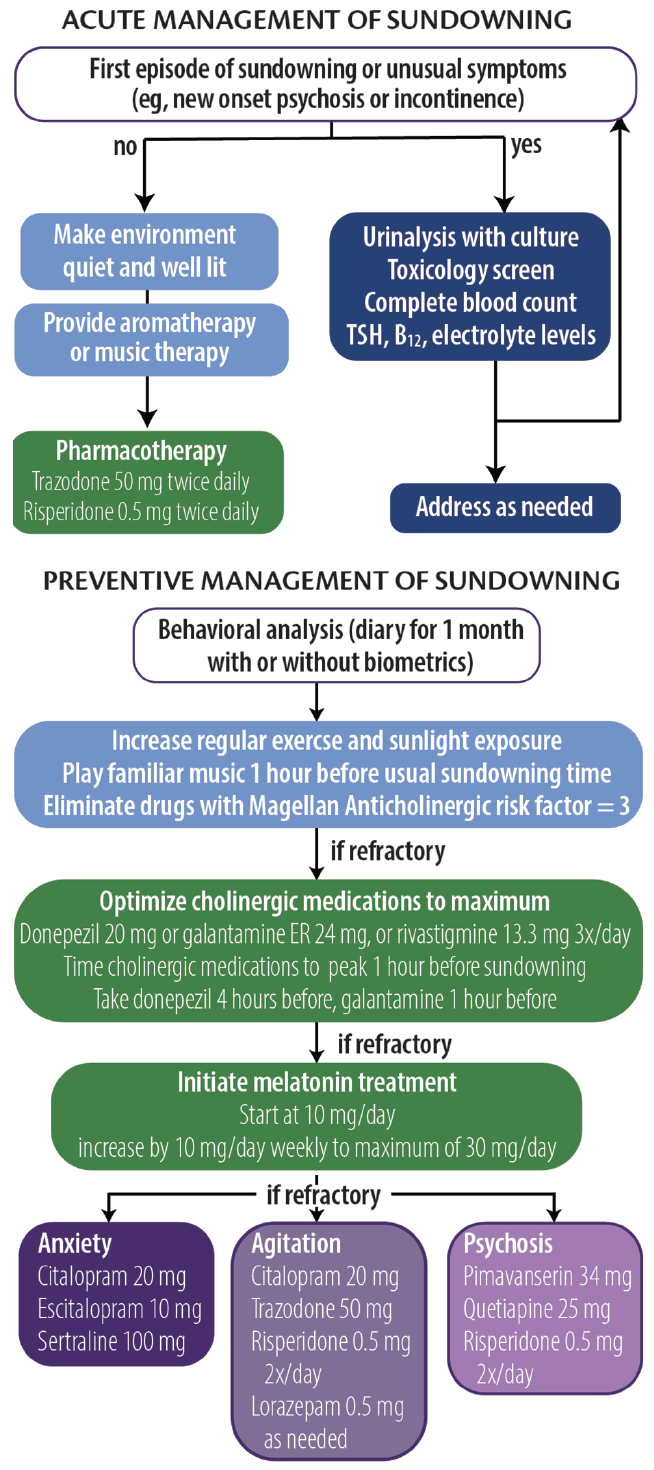

Analogous to headache management, approaches to sundowning can be broadly categorized as acute or preventive (Figure 2). Although preventive approaches may be more effective, caregivers may be able to reduce NPS associated with sundowning when it occurs.

Figure 2. Acute and preventative approaches to sundowning. Abbreviation: TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Acute Management

The PLST model can be used to identify any and all triggers that may contribute to sundowning episodes. For a first or unusual episode, it is recommended that a targeted medical and laboratory evaluation including urine culture, complete blood count, drug toxicology, and levels of electrolytes, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B 12 be obtained. During an episode, whenever possible, a quiet, well-lit environment should be provided. Aromatherapy and familiar music at a medium volume may also help reduce anxiety and agitation. For persons at risk of hurting themselves or others, a low-dose psychotropic medication (eg, trazodone 50 mg repeated 1 hour later followed by risperidone 0.5 mg) may be necessary.

Preventive Management

In our clinical experience, prevention strategies may reduce the severity and frequency of sundowning. The first step is to conduct a behavioral analysis of the sundowning behavior. We recommend a daily journal be maintained for at least 1 month to document the types of behavior (eg, agitation, anxiety, psychosis, and disorientation) that occur, time of onset, and any extenuating circumstances that may have contributed to episodes of sundowning. Care partners can also provide information regarding medication administration and sleeping behavior to inform the analysis. The health care professional should analyze the journal, looking for patterns and correlations with other factors (eg, shift changes at care homes or changes to daily routines). The journal can be supported by biometric data from wearable technologies that provide objective measures of physical activity and sleep, which can be helpful in tailoring both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches.

We also recommend increasing the amount of regular exercise and sunlight exposure, preferably in the early afternoon. Caregivers are advised to start playing soothing or familiar music approximately 1 hour before sundowning behavior typically starts. Any medication with Magellan Anticholinergic Risk Scale scores of 3 should be eliminated, which requires scrutiny of medication lists. 25 Optimization of cognitive-enhancing medication doses and timing administration such that mean peak plasma concentrations are reached 1 hour before a person’s typical time of sundowning behavior may be beneficial.

If problematic sundowning behavior still persists, we recommend melatonin supplementation at an initial dose of 10 mg taken at nighttime, followed by a weekly increase by 10 mg to a maximum dose of 30 mg. This regimen is instituted regardless of reported sleep quality. If symptoms persist, the next step is to target NPS based on the individual’s most recent NPI-Q profile. The mantra of “start low and go slow” should guide therapeutic interventions, waiting at least 2 weeks before altering doses. In general, antidepressants are preferred first steps unless safety concerns necessitate more proactive approaches.

1. Cummings J, Ritter A, Rothenberg K. Advances in management of neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Psychiatry Rep . 2019;21(8):79.

2. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Nuti A, Danti S. Wandering and dementia. Psychogeriatrics . 2014;14(2):135-142.

3. Algase DL, Moore DH, Vandeweerd C, Gavin-Dreschnack DJ. Mapping the maze of terms and definitions in dementia-related wandering. Aging Ment Health . 2007;11(6):686-698.

4. Petonito G, Muschert GW, Carr DC, Kinney JM, Robbins EJ, Brown JS. Programs to locate missing and critically wandering elders: a critical review and a call for multiphasic evaluation. Gerontologist. 2013;53(1):17-25.

5. Rowe MA, Vandeveer SS, Greenblum CA, et al. Persons with dementia missing in the community: is it wandering or something unique? BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:28.

6. Hope T, Keene J, McShane RH, Fairburn CG, Gedling K, Jacoby R. Wandering in dementia: a longitudinal study. Int Psychogeriatr . 2001;13(2):137-147.

7. Ballard CG, Mohan RNC, Bannister C, Handy S, Patel A. Wandering in dementia sufferers. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1991;6:611-614.

8. Klein DA, Steinberg M, Galik E, et al. Wandering behaviour in community-residing persons with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 1999;14(4):272-279.

9. Yang Y, Kwak YT. FDG PET findings according to wandering patterns of patients with drug-naïve Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Neurocogn Disord . 2018;17(3):90-99.

10. Hope RA, Fairburn CG. The nature of wandering in dementia: a community-based study. Int J Geriat Psychiatry . 1990;5(4):239-245.

11. Neubauer NA, Azad-Khaneghah P, Miguel-Cruz A, Liu L. What do we know about strategies to manage dementia-related wandering? A scoping review. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:615-628.

12. Neubauer NA, Lapierre N, Ríos-Rincón A, Miguel-Cruz A, Rousseau J, Liu L. What do we know about technologies for dementia-related wandering? A scoping review: Examen de la portée: Que savons-nous à propos des technologies de gestion de l’errance liée à la démence? Can J Occup Ther. 2018;85(3):196-208.

13. O’Neill D. Should patients with dementia who wander be electronically tagged? No. BMJ. 2013;346:f3606.

14. Logsdon RG, Teri L, McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Kukull WA, Larson EB. Wandering: a significant problem among community-residing individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(5):P294-P299.

15. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(9):1991]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

16. Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci . 2000;12(2):233-239.

17. Canevelli M, Valletta M, Trebbastoni A, et al. Sundowning in dementia: clinical relevance, pathophysiological determinants, and therapeutic approaches. Front Med (Lausanne) . 2016;3:73.

18. Gallagher-Thompson D, Brooks JO 3rd, Bliwise D, Leader J, Yesavage JA. The relations among caregiver stress, “sundowning” symptoms, and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40(8):807-810.

19. Madden KM, Feldman B. Weekly, seasonal, and geographic patterns in health contemplations about sundown syndrome: an ecological correlational study. JMIR Aging 2019;2(1):e13302. doi:10.2196/13302

20. Wang JL, Lim AS, Chiang WY, et al. Suprachiasmatic neuron numbers and rest-activity circadian rhythms in older humans. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(2):317-322.

21. Weinshenker D. Functional consequences of locus coeruleus degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res . 2008;5(3):342-345.

22. Smith M, Gerdner LA, Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. History, development, and future of the progressively lowered stress threshold: a conceptual model for dementia care. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2004;52(10):1755-1760.

23. Cohen-Mansfield J, Garfinkel D, Lipson S. Melatonin for treatment of sundowning in elderly persons with dementia - a preliminary study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr . 2000;31(1):65-76.

24. Gauthier S, Feldman H, Hecker J, et al. Efficacy of donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002;14(4):389-404.

25. Rudolph JL, Salow MJ, Angelini MC, McGlinchey RE. The anticholinergic risk scale and anticholinergic adverse effects in older persons. Arch Intern Med . 2008;168(5):508-513.

TT reports no disclosures AR's work on this paper was supported by NIGMS P20GM109025

Taylor Thomas, BA

University of Nevada-Las Vegas School of Medicine Las Vegas, NV

Aaron Ritter, MD

Clinical Assistant Professor of Neurology Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health Las Vegas, NV

Treating Dementias With Care Partners in Mind

Dylan Wint, MD

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia

Jeffrey L. Cummings, MD, ScD

This Month's Issue

Abdalmalik Bin Khunayfir, MD; and Brian Appleby, MD

Anne Møller Witt, MD; Louise Sloth Kodal, MD; and Tina Dysgaard, MedScD

Julia Greenberg, MD; Kaiulani Houston, MD, PhD; Kevin Spiegler, MD, PhD; Sujata Thawani, MD, MPH; Harold Weinberg, MD, PhD; and Ilya Kister, MD

Related Articles

Simon Ducharme, MD, MSc, FRCPC

Sign up to receive new issue alerts and news updates from Practical Neurology®.

Related News

- Português Br

- Journalist Pass

Alzheimer’s and dementia: Understand wandering and how to address it

Dana Sparks

Share this:

Wandering and becoming lost is common among people with Alzheimer's disease or other disorders causing dementia. This behavior can happen in the early stages of dementia — even if the person has never wandered in the past.

Understand wandering

If a person with dementia is returning from regular walks or drives later than usual or is forgetting how to get to familiar places, he or she may be wandering.

There are many reasons why a person who has dementia might wander, including:

- Stress or fear. The person with dementia might wander as a reaction to feeling nervous in a crowded area, such as a restaurant.

- Searching. He or she might get lost while searching for something or someone, such as past friends.

- Basic needs. He or she might be looking for a bathroom or food or want to go outdoors.

- Following past routines. He or she might try to go to work or buy groceries.

- Visual-spatial problems. He or she can get lost even in familiar places because dementia affects the parts of the brain important for visual guidance and navigation.

Also, the risk of wandering might be higher for men than women.

Prevent wandering

Wandering isn't necessarily harmful if it occurs in a safe and controlled environment. However, wandering can pose safety issues — especially in very hot and cold temperatures or if the person with dementia ends up in a secluded area.

To prevent unsafe wandering, identify the times of day that wandering might occur. Plan meaningful activities to keep the person with dementia better engaged. If the person is searching for a spouse or wants to "go home," avoid correcting him or her. Instead, consider ways to validate and explore the person's feelings. If the person feels abandoned or disoriented, provide reassurance that he or she is safe.

Also, make sure the person's basic needs are regularly met and consider avoiding busy or crowded places.

Take precautions

To keep your loved one safe:

- Provide supervision. Continuous supervision is ideal. Be sure that someone is home with the person at all times. Stay with the person when in a new or changed environment. Don't leave the person alone in a car.

- Install alarms and locks. Various devices can alert you that the person with dementia is on the move. You might place pressure-sensitive alarm mats at the door or at the person's bedside, put warning bells on doors, use childproof covers on doorknobs or install an alarm system that chimes when a door is opened. If the person tends to unlock doors, install sliding bolt locks out of his or her line of sight.

- Camouflage doors. Place removable curtains over doors. Cover doors with paint or wallpaper that matches the surrounding walls. Or place a scenic poster on the door or a sign that says "Stop" or "Do not enter."

- Keep keys out of sight. If the person with dementia is no longer driving, hide the car keys. Also, keep out of sight shoes, coats, hats and other items that might be associated with leaving home.

Ensure a safe return

Wanderers who get lost can be difficult to find because they often react unpredictably. For example, they might not call for help or respond to searchers' calls. Once found, wanderers might not remember their names or where they live.

If you are caring for someone who might wander, inform the local police, your neighbors and other close contacts. Compile a list of emergency phone numbers in case you can't find the person with dementia. Keep on hand a recent photo or video of the person, his or her medical information, and a list of places that he or she might wander to, such as previous homes or places of work.

Have the person carry an identification card or wear a medical bracelet, and place labels in the person's garments. Also, consider enrolling in the MedicAlert and Alzheimer's Association safe-return program. For a fee, participants receive an identification bracelet, necklace or clothing tags and access to 24-hour support in case of emergency. You also might have your loved one wear a GPS or other tracking device.

If the person with dementia wanders, search the immediate area for no more than 15 minutes and then contact local authorities and the safe-return program — if you've enrolled. The sooner you seek help, the sooner the person is likely to be found.

This article is written by Mayo Clinic Staff . Find more health and medical information on mayoclinic.org .

- Answers to common questions about whether vaccines are safe, effective and necessary Consumer Health: Treating and living with HIV and AIDS

Related Articles

Enter a Search Term

How to prevent wandering in alzheimer’s patients.

- Expert Advice

Wandering is one of the most dangerous behaviors associated with Alzheimer’s disease. An Alzheimer’s patient who wanders outside alone can easily become lost, confused, injured, and even die from exposure to harsh weather or other safety risks.

An estimated 6 in 10 people with Alzheimer’s disease are at risk of wandering when they become confused or disoriented. This can happen at any stage of the disease. It is important to take steps to prevent wandering and know what to do in an emergency.

To prevent wandering, it helps to understand what causes a person with Alzheimer’s to wander.

Some common reasons for wandering are:

- Confusion: The person with Alzheimer’s disease doesn’t realize that he is at home and sets out to “find” his home.

- Delusions: He may be reliving an anxiety or responsibility from the long-ago past, such as going to work or caring for a child.

- Escape from a real or perceived threat: A person with Alzheimer’s disease can be frightened by noise, a stranger who visits, or even the belief that his or her caregiver is trying to hurt him or her.

- Agitation: This is a common symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and it can be made worse by some medications. Boredom and restlessness also may be brought on by a lack of exercise and other stimulation, such as searching for a person, a place, or an item that was lost.

How to Prevent Wandering

A person with Alzheimer’s disease who is restless or has a tendency to wander should never be left alone. And even with another adult in the house, the caregiver should take steps to lessen the danger that the person will exit the house or building.

Steps can include:

- Ensuring all basic needs are met, such as toileting, nutrition, and thirst.

- Checking with a doctor to determine whether medication may be causing the behavior.

- Giving the person something repetitive to do, such as rocking in a rocking chair or glider, sweeping the floor, or folding clothes.

- Providing the person a safe, uncluttered space. Since pacing sometimes happens, provide a clear path for pacing and eliminate rugs and obstacles that could cause trips and falls.

- Covering doors with “camouflage” posters that make them look like bookshelves or something other than a door. Doors can also be painted the same color as walls to make them “disappear.”

- Placing red “STOP” signs on a door (this may be effective at stopping someone from going out).

- Adding deadbolts to all doors leading to the outside, and keep the keys in a safe place where the patient can’t get to them. To reduce frustration, place locks out of the line of sight. Never lock someone with Alzheimer’s or dementia in the home alone.

- Installing special latches where needed on inside cupboards and doors, and safety devices on all windows to limit how far they can be opened.

- Looking for assistive safety technologies available from hardware stores or home security vendors. These include motion and bed occupancy sensors; window and door sensors that set off alarms when opened; driveway sensors; and wireless home security systems.

- Installing a fence around the house with a lockable gate.

- Obtaining a medical identification bracelet for the person that includes her name, the words “memory loss,” and an emergency phone number. These bracelets are sold in drugstores and online. Make sure it is worn at all times.

- Investing in a GPS or similar wearable tracking device that makes it possible to monitor a person’s whereabouts and help you locate him quickly. Shoes, watches, necklaces, and ankle bracelets are being manufactured with these devices and can be purchased from vendor websites (see Resources section at the end of this brochure).

- Notifying your neighbors and community members that the individual has a tendency to wander, and ask them to alert you immediately if they see her out alone.

Although wandering is one of the most dangerous behaviors associated with Alzheimer’s disease, there are some ways to prevent or manage the risk. We want to educate and inform caregivers in order to help you remain confident in the face of this difficult disease. For more information about Alzheimer’s disease, visit www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers .

Help find a cure

Donate to help end Alzheimer’s Disease

I would like to donate

Stay in touch.

Receive Alzheimer’s research updates and inspiring stories

- Own a Franchise

- Jean Griswold Foundation

Back to the blog

Dementia: Wandering at Night

Date: April 5, 2022

Author: Jayne Stewart

Dementia Care

If you have a loved one with dementia, wandering at night may be one of the most worrisome symptoms to manage. When determining how to keep dementia patients from wandering, you must understand how dementia progresses.

Why do dementia patients wander at night.

It is common for people with dementia to become confused and disoriented in all stages of the disease, and in some cases that involve wandering. Dementia patients lose the ability to recognize familiar locations such as their own homes once they wander out the door.

Six in ten people living with dementia have wandered at least once; many do so repeatedly. This is not only a safety risk for the person who is wandering, but it also causes family members and caregivers enormous stress. When a person is confused, they may not remember their address or a relative’s name who could come to their rescue. In the latter stages of dementia, they may not even remember their own name.

Do all dementia patients wander?

Not all people with dementia wander. If a person is restless and can walk around in a safe, controlled environment wandering can be a way to relieve anxiety.

It’s when a person is frightened, over-stressed, or feeling abandoned that it causes a problem, especially at night.

Let’s look at some triggers for nighttime wandering and how to keep dementia patients from wandering by modifying schedules and the environment.

- Looking for a bathroom . This is one of the main triggers for wandering at night. If the person wakes up because of the urge to urinate, he or she may open the wrong door and end up in the wrong room, in the garage, or outside.

- Waking up and not knowing where they are . In this case, the person sees nothing that looks familiar and may walk outside trying to get “home.” Many times, home is the place where the individual grew up.

- Poor sleep habits can be a trigger for nighttime wandering. If your loved one wakes up at odd times during the night, you should examine the daytime schedule. Napping and intermittent snoozing during the day can lead to restless or sleepless nights. Try to provide stimulating activities during the day to assure your loved one is tired and ready for sleep at night.

- Hunger can also be a reason for waking up and wandering. Make sure a bedtime snack is part of the nightly routine.

- Being too hot or too cold. Adjust the temperature to assure comfort and be sure to provide sleepwear and bedding that is season-appropriate.

Download Our Early Signs of Dementia Guide

What are wandering prevention devices? How to stop the elderly from leaving the house.

If these tips fail to stop the wandering, you need to be sure your loved one is safe despite the tendency to wander, especially at night.

You can start by putting a latch or deadbolt on all doors leading to the outside. Be sure to place them either above or below eye level. Never lock a person with dementia in the house by themselves. For safety reasons, another person should always be in the home in case of fire or any other emergency.

Wander prevention devices such as alarms, motion sensors, and pressure-sensitive mats can be installed in the home to alert others when the patient is attempting to exit the home.

You can also use a wearable GPS tracking device such as a bracelet, necklace, or anklet. These devices will help emergency personnel locate your loved one quickly if he does manage to wander away from the house.

Each person and situation are different. The goal is to keep your loved one safe, protected, and content in the least restrictive environment possible.

Related Blog Posts

Sudden Increased Appetite in Elderly Adults

Forgetful in Old Age: Elderly Forgetfulness

Do Patients with Dementia Lose Weight?

Advertisement

Caregivers Journey Through Experiences of People Living with Dementia and History of Wandering Behaviour: An Indian Case Series

- Case Discussion

- Published: 07 November 2023

- Volume 11 , pages 107–114, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- K. N. Anu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5890-8845 1 ,

- A. Thirumoorthy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1120-9259 1 ,

- Sojan Antony ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6543-5361 1 ,

- Thomas Gregor Isaac ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3148-3466 2 ,

- Cicil. R. Vasanthra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2202-3791 1 &

- P. T. Sivakumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9802-2520 2

177 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Wandering is one of the major behavioural symptoms of dementia contributing to increased caregiver burden. Understanding the caregivers’ challenges help the mental health professionals to develop a feasible care plan relevant to Indian context. To explore the caregivers’ experience of managing wandering behaviour among persons with dementia. Three case studies were selected from the family caregiver population and who made efforts to manage wandering behaviour in person with dementia. Interview method was used to understand the experience of caregivers. The mean age of the caregivers was 49 years, mean age of the persons with wandering in dementia was 73 and mean duration of illness was 2 years. All the three caregivers used supervision and locking the doors of their houses as key strategies to prevent the wandering behaviour among the persons with dementia. Other prominent strategies were seeking community support and listing out the destinations in which the person is found commonly. Keeping an identity card, planned activities of daily living, restricted movement, safety planning and division of caregiving responsibility were also applied in management of wandering by family caregivers. Caregivers experience significant challenges in managing wandering behaviour. Many of them could manange wandering behaviour with the support of available resources in community. Additional training and support would enhance the quality of caregivers’ life.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Agrawal AK, Gowda M, Achary U, Gowda GS, Harbishettar V. Approach to Management of Wandering in Dementia: Ethical and Legal Issue. Indian J Psychol Med. 2021 Sep 1;43(5_suppl):S53–9.

Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Nuti A, Danti S. Wandering and dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2014;14(2):135–42.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dias A, Patel V. Closing the treatment gap for dementia in India. Indian J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2009 Jan [cited 2023 Apr 20];51 Suppl 1:S93-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21416026