- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

Today in media history: The Pulitzer Prize-winning story “Enrique’s Journey”

On October 6, 2002, chapter five of the story, “Enrique’s Journey,” by Sonia Nazario appeared in the Los Angeles Times . The story was awarded the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing and later became a book .

The Pulitzer award citation : “Awarded to Sonia Nazario of Los Angeles Times for ‘Enrique’s Journey,’ her touching, exhaustively reported story of a Honduran boy’s perilous search for his mother who had migrated to the United States.”

This is how the story begins:

“Enrique’s Journey” — Chapter One — “The Boy Left Behind” “The boy does not understand. His mother is not talking to him. She will not even look at him. Enrique has no hint of what she is going to do. Lourdes knows. She understands, as only a mother can, the terror she is about to inflict, the ache Enrique will feel and finally the emptiness. What will become of him? Already he will not let anyone else feed or bathe him. He loves her deeply, as only a son can. With Lourdes, he is a chatterbox. ‘Mira, Mami.’ Look, Mom, he says softly, asking her questions about everything he sees. Without her, he is so shy it is crushing. Slowly, she walks out onto the porch. Enrique clings to her pant leg. Beside her, he is tiny. Lourdes loves him so much she cannot bring herself to say a word. She cannot carry his picture. It would melt her resolve. She cannot hug him. He is 5 years old. ….But Lourdes cannot face Enrique. He will remember only one thing that she says to him: ‘Don’t forget to go to church this afternoon.’ It is Jan. 29, 1989. His mother steps off the porch. She walks away. ‘¿Donde esta mi mami?’ Enrique cries, over and over. ‘Where is my mom?’ His mother never returns, and that decides Enrique’s fate. As a teenager — indeed, still a child — he will set out for the U.S. on his own to search for her….”

Here are links to the other chapters of “Enrique’s Journey.”

“Enrique’s Journey” — Chapter Two

“Enrique’s Journey” — Chapter Three

“Enrique’s Journey” — Chapter Four

“Enrique’s Journey” — Chapter Five

“Enrique’s Journey” — Chapter Six

Opinion | Gannett fires editor for talking to Poynter, and other media news

Firing a single mother of three who was speaking up for more newsroom resources is a horrible look that deserves scrutiny and criticism.

Donald Trump repeated inaccurate claims on the economy in a local news interview in Pennsylvania

Trump repeated a bevy of inaccurate claims about the economy during an interview with WGAL-TV, a Lancaster, Pennsylvania, station

Opinion | Gannett fired an editor for talking to me

Sarah Leach spoke to Poynter in an attempt to staff up her team. She may have been successful, even if she won't be at Gannett to see it through.

Opinion | Kristi Noem’s media headaches now extend to conservative outlets

The South Dakota governor’s past few days have been so bad that she’s canceling on conservative media. Conservative media might soon cancel on her.

Q&A: HBO Max’s new ‘Girls on the Bus’ set out to show a cool, fun side of journalism

Former New York Times reporter and show co-creator Amy Chozick on how fact inspired fiction, pitfalls she avoided and today’s media environment

Comments are closed.

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

Enrique's Journey

About the author, sonia nazario.

September 2013, No. 3 Vol. L, Migration

O ne day, I was having a conversation in my kitchen with Carmen, who came to clean my house twice a month.

I asked her: did she want to have more children? I thought she just had one young son.

Carmen was normally chatty, happy. But when I asked her about having more children, she fell stone silent. Then, she started sobbing.

She told me she had left four children behind in Guatemala. She said she was a single mother—her husband had left her for another woman. Most days, she could only feed her children once, maybe twice. At night, they cried with hunger.

She showed me how she would gently roll them over in bed, and tell them: “Sleep face down, so your stomach doesn’t growl so much.”

She has left her four children with their grandmother in Guatemala and come north to work in Los Angeles, and hasn’t seen them in 12 years.

I stood in my kitchen, stunned, asking myself what kind of desperation does it take for a mother to leave her children, go 2,000 miles away, without knowing when or if she would see them again? I soon learned three things: worldwide, migrants are no longer predominantly men. Today, of the more than 214 million migrants circling the globe, more women migrate than men. Many of these women, like my housecleaner, were leaving children behind. In doing so, they were creating a new class of children—so-called “mobility orphans”.

Save the Children estimates there are tens of millions of these mobility orphans worldwide—a million left behind each year in Sri Lanka alone. And, as would later become the case with my housecleaner, children left behind and in desperation after years of not seeing their mothers often set off on their own to find them, in what for many becomes a modern-day odyssey.

Latin America was the first developing region in 1990 to have as many women migrate as men. In parts of the past decade, three quarters of migrants leaving the Philippines and Indonesia were women.

The United Nations has long focused on the benefits of migration, both for sending and receiving countries. I stood in my kitchen that morning with my housecleaner wondering: what were the benefits? What were the costs?

Those questions launched me on an amazing journey—to Honduras, and on top of freight trains for three months travelling up the migrant routes through Mexico. Women migrants, I learned, came to take care of other people’s children as nannies, but weren’t there to see their own children take their first steps, or hear their first words.

In Latin America, growing family disintegration spurred many single mothers to migrate. In what became the largest wave of migration in United States history since 1990, 51 per cent of those coming were women and children.

Women told me when their children cried at night, they filled a big glass with water, stirred in a teaspoon of sugar or a dollop of tortilla dough, to fill their stomachs with something. To them, leaving was the ultimate act of love; their sacrifice meant their children might eat and perhaps even study past the third grade.

All the women I talked to told the same story: they left their children with one promise: I’ll be back in a year or two—at most. Life in the United States was much harder than advertised. Often, separations stretched into five or ten years—or more. Their children got desperate to be with them again. They told themselves: if my mom can’t come back to me or send for me, I’m going to find her!

Today, there is a small army of children, about 100,000 per year, heading north to the United States unlawfully and alone—without either parent—from Mexico and Central America. The number of unaccompanied children doubled in the past year and is expected to jump again this year.

Children aren’t just coming to be with their mothers; they are fleeing increasing violence fuelled by transnational gangs vying for turf to move drugs north. These battles have given Honduras and El Salvador the highest homicide rates in the world. In El Salvador, 9-year-old boys describe being recruited by gangs as they walk home from elementary school. The warning: join, or we will kill your parents, rape your sister.

I wrote about the millions of mobility orphans through the true story of one boy, Enrique, whose mother leaves him in Honduras when he is five years old to work in the United States. Enrique begs his paternal grandmother, who he is left with, “ Cuando vuelve mi mami ? When is my mother coming back?” Desperate to be with her, 11 years later he sets off on his own to go find her. All he has is a scrap of paper with her telephone number, and a burning question: Does she still love me?

Virtually penniless, he travels the only way he can, clinging to the tops of freight trains up the length of Mexico. Thousands of children make this journey every year in search of their mothers. The youngest I heard about was a 7-year-old boy. I travelled with a 12-year-old boy going in search of his mother. He was traversing four countries, alone, navigating by little more than the arc of the sun.

From the moment Enrique crossed into Mexico, he was hunted down like an animal by bandits alongside the tracks, gangsters who control the train tops, and corrupt cops. Today, the most feared narco-trafficking cartel in Mexico, the Zetas, controls the train routes; they are kidnapping 22,000 migrants a year for ransom. Their favorite target: children, using the slip of paper they carry with their mother’s telephone number to make demands in exchange for the child’s life. Many children, who must get on and off the trains away from the stations and while they are moving, lose arms and legs to the train, called el tren de la muerte , the train of death.

Enrique is nearly beaten to death by six thugs on top of a freight train. He escapes one of the men who is strangling him by flinging himself off the fast-moving train.

To write Enrique’s story, to show what this journey is like for so many children, I spent two weeks with him in Mexico near the United States border, and then went to Enrique’s house in Honduras. From there, I did the journey, step by step, exactly as Enrique had just weeks before. I travelled for months, 1,600 miles, half of that on the top of seven freight trains. I had many close calls and difficult experiences. A big tree branch almost swept me off a train top. It got the teen behind me, who flew off and down to the churning wheels below. When I returned home to Los Angeles, I had nightmares of gangsters running after me on top of trains.

Despite what I had been through, I understood I had experienced just a fraction of the danger children go through on this journey. The journey also helped me understand what drives these women and mobility orphans out of their homelands. In Honduras, help wanted ads told women that if they were 28 years or older to not bother applying. The children of mothers who stayed in Honduras in Enrique’s neighbourhood often ended up working as scavengers in this horrific dump. The journey helped me see a kind of determination I could never have imagined—determination no wall will stop. Enrique tries eight times to get through Mexico—braving 122 days and 12,000 miles.

I saw migrants inflicted with horrible cruelty, and also amazing acts of kindness. In South-Central Mexico, when people in tiny towns along the tracks heard the whistle of the train, I watched them rush out of their homes with bundles of food in their arms. They would wave, smile and shout out to migrants perched on top of the trains. They threw bread, tortillas, whatever fruit was in season—bananas, pineapples, or oranges. If they didn’t have even that, they lined up next to the tracks, and sent out a prayer to the migrants atop the train.

These were the poorest Mexicans, who could barely feed their own children. They gave, they said, because it was the right thing to do, the Christian thing to do, what Jesus would do standing in their shoes.

Migration, the movement of people, is one of the biggest social and economic issues of our time. I come at this issue with migration in my blood—my grandparents fled Syria and Poland for Argentina; my parents migrated from Argentina to the United States—and as someone who has written about the issue for nearly three decades. From my perspective in the United States, I see it as an issue with many shades of gray, with winners and losers.

The influx of migrants since 1990, the largest in United States history, has indisputably helped; migrants have done jobs Americans clearly don’t want to do and helped spur the nation’s $13 trillion economy. Migrants, per one study, have cut by 5 per cent the cost of all goods and services everyone in the United States buys.

But there have been clear consequences. Take the 1 in 14 Americans, mostly African-American and Latino, who don’t have a high school degree and are among the most disadvantaged in our society. They have seen their wages depressed because of competition from migrants.

Migrant women and children have also been hurt. Certainly, mothers who migrate are able to send money home and, as a result, their children are able to eat well and study. But after years apart, most of these children resent and even walk up to the line of hating their mothers for leaving them. They feel abandoned. They tell their mothers that even a dog doesn’t leave its litter. Many mothers lose what’s most precious to them—the love of their children. Resentful children disproportionately join gangs or get pregnant with an older man, searching for the love they dreamed of having when they finally reunite with their mothers.

Studies show mobility orphans have higher levels of depression, lower academic levels, and greater physical and emotional problems. Drug abuse is more common. Enrique turned to glue sniffing in Honduras to fill the void of his mother’s absence, an addiction he has found hard to overcome.

In October 2013, as the United Nations holds a second High-level Dialogue on International Migration and Development, it will once again focus on how to improve the lives of all migrants, especially mobility orphans.

The migrants I met in Central America and along the train tracks in Mexico stressed that if they could stay at home with all they love—their family, culture, language, and especially their children—they wouldn’t leave. Women said they felt forced to leave, and told me that if they could feed their children, clothe them and send them to school, they would have stayed.

This exodus, they said, must be tackled at its source, in terms of helping to create more jobs in developing countries. For the United States, that means working on the lack of opportunity for women in just four countries that send three-quarters of the women who come to the United States without permission. We must bring every thing to this task: more microloans to help women start businesses, trade policies that give preference to goods from these countries and help promoting education for girls. We must promote more democratic governments that redistribute wealth, the opposite of what the United States has historically done in the region. We must take billions spent on useless things like walls and put that money into targeted economic development.

Readers of Enrique’s Journey , perhaps the most widely read book about immigrants in the United States today, have taken this approach to heart. The story of one boy has caused them to organize to build schools, water systems, and homes for single mothers in Central America. One California high school raised $9,000 to provide a microloan to help coffee-growing women in Olopa, Guatemala expand their business, so that more mothers could stay at home with their children.

Today, the United States Congress is debating the same old approach to regulating migration: amped up border enforcement, guest worker programmes, and pathways to citizenship—all approaches that have done little to help people stay at home. These approaches sealed in migrants who would prefer to circulate back home, brought people as temporary workers who never left, and caused the number of unlawful migrants to grow anew. Too often, we get the migration policy that the strongest prison, agricultural, high tech and business lobbies push for.

There is still little to no discussion of immigration as an international development issue, even though presidential commissions have advocated this as the only long-term solution to unlawful migration since the 1970s. Instead, the focus has been on open trade, the elusive promise of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement, to lift all boats through development. And, countries have furiously built walls.

What if, instead, each developed country took on the task of job creation for women in the handful of countries that send them immigrants? Imagine if the United Nations worked to coordinate a small percentage of the $406 billion in yearly remittances that flow from migrants in developed to developing countries to produce projects that create jobs.

Migrants shouldn’t have to rely on food throwers—the kindness of strangers—for help. The United Nations, governments in developed countries, and non-governmental organizations must become their champion in changing the direction of what must be done.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Thirty Years On, Leaders Need to Recommit to the International Conference on Population and Development Agenda

With the gains from the Cairo conference now in peril, the population and development framework is more relevant than ever. At the end of April 2024, countries will convene to review the progress made on the ICPD agenda during the annual session of the Commission on Population and Development.

The LDC Future Forum: Accelerating the Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals in the Least Developed Countries

The desired outcome of the LDC Future Forums is the dissemination of practical and evidence-based case studies, solutions and policy recommendations for achieving sustainable development.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

For two centuries, emancipated Black people have been calling for reparations for the crimes committed against them.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

Reviews of Enrique's Journey by Sonia Nazario

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Enrique's Journey

by Sonia Nazario

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

- Biography & Memoir

- History, Current Affairs and Religion

- Central & S. America, Mexico, Caribbean

- Contemporary

- Adult-YA Crossover Fiction

- Immigrants & Expats

- Latinx Authors

Rate this book

About this Book

- Reading Guide

Book Summary

A true story from award-winning journalist Sonia Nazario recounting the odyssey of a Honduran boy who braves hardship and peril to reach his mother in the United States.

In this astonishing true story, award-winning journalist Sonia Nazario recounts the unforgettable odyssey of a Honduran boy who braves unimaginable hardship and peril to reach his mother in the United States. When Enrique is five years old, his mother, Lourdes, too poor to feed her children, leaves Honduras to work in the United States. The move allows her to send money back home to Enrique so he can eat better and go to school past the third grade. Lourdes promises Enrique she will return quickly. But she struggles in America. Years pass. He begs for his mother to come back. Without her, he becomes lonely and troubled. When she calls, Lourdes tells him to be patient. Enrique despairs of ever seeing her again. After eleven years apart, he decides he will go find her. Enrique sets off alone from Tegucigalpa, with little more than a slip of paper bearing his mother's North Carolina telephone number. Without money, he will make the dangerous and illegal trek up the length of Mexico the only way he can – clinging to the sides and tops of freight trains. With gritty determination and a deep longing to be by his mother's side, Enrique travels through hostile, unknown worlds. Each step of the way through Mexico, he and other migrants, many of them children, are hunted like animals. Gangsters control the tops of the trains. Bandits rob and kill migrants up and down the tracks. Corrupt cops all along the route are out to fleece and deport them. To evade Mexican police and immigration authorities, they must jump onto and off the moving boxcars they call El Tren de la Muerte- The Train of Death. Enrique pushes forward using his wit, courage, and hope - and the kindness of strangers. It is an epic journey, one thousands of immigrant children make each year to find their mothers in the United States. Based on the Los Angeles Times newspaper series that won two Pulitzer Prizes, one for feature writing and another for feature photography, Enrique's Journey is the timeless story of families torn apart, the yearning to be together again, and a boy who will risk his life to find the mother he loves.

The Boy Left Behind

The boy does not understand. His mother is not talking to him. She will not even look at him. Enrique has no hint of what she is going to do. Lourdes knows. She understands, as only a mother can, the terror she is about to inflict, the ache Enrique will feel, and finally the emptiness. What will become of him? Already he will not let anyone else feed or bathe him. He loves her deeply, as only a son can. With Lourdes, he is openly affectionate. "Dame pico, mami. Give me a kiss, Mom," he pleads, over and over, pursing his lips. With Lourdes, he is a chatterbox. "Mira, mami. Look, Mom," he says softly, asking her questions about everything he sees. Without her, he is so shy it is crushing. Slowly, she walks out onto the porch. Enrique clings to her pant leg. Beside her, he is tiny. Lourdes loves him so much she cannot bring herself to say a word. She cannot carry his picture. It would melt her resolve. She cannot hug him. He is five years old...

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews, bookbrowse review.

Few would disagree that illegal immigration is a problem for the USA and for other Western countries, but it's all too easy to think of it as a statistical problem, not the human problem that it is. At the end of the day Enrique's Journey is not about illegal immigration or people stealing jobs from USA workers, it's about families, and the desperately hard choices that too many have to make... continued

Full Review (306 words) This review is available to non-members for a limited time. For full access, become a member today .

(Reviewed by BookBrowse Review Team ).

Write your own review!

Beyond the Book

Quick Facts (from Enrique's Journey )

- About 700,000 immigrants enter the United States illegally each year. In recent years the demographics have changed with many more single mothers arriving.

- Nearly three-quarters of the 48,000 children who migrate alone to "el Norte" through Central America and Mexico each year are in search of a single mother who has left them behind. According to the Department of Homeland Security, the median age of child migrants is 15; the majority are male; some are as young as 7 years.

- In Los Angeles, 82% of live-in nannies and one in four housecleaners are mothers who have at least one child in their home country.

- According to the Center for Immigration Studies, illegal workers donate $6.4 billion ...

This "beyond the book" feature is available to non-members for a limited time. Join today for full access.

Read-Alikes

- Genres & Themes

If you liked Enrique's Journey, try these:

We Are Not from Here

by Jenny Torres Sanchez

Published 2021

About this book

More by this author

Winner of the 2020 BookBrowse Award for Best Young Adult Novel A poignant novel of desperation, escape, and survival across the U.S.-Mexico border, inspired by current events.

A Good Provider Is One Who Leaves

by Jason DeParle

Published 2020

The definitive chronicle of our new age of global migration, told through the multi-generational saga of a Filipino family, by a veteran New York Times reporter and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist.

Books with similar themes

Support bookbrowse.

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Flower Sisters by Michelle Collins Anderson

From the new Fannie Flagg of the Ozarks, a richly-woven story of family, forgiveness, and reinvention.

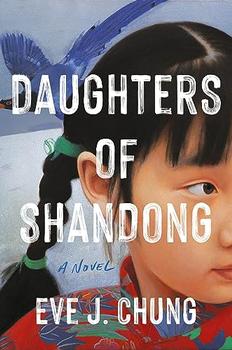

Daughters of Shandong by Eve J. Chung

Eve J. Chung's debut novel recounts a family's flight to Taiwan during China's Communist revolution.

Enrique’s Journey

Sonia nazario, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Enrique’s Journey | Chapter Six: At Journey’s End, a Dark River, Perhaps a New Life

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

At 1 a.m., Enrique waits on the edge of the water.

“If you get caught, I don’t know you,” says the man called El Tirindaro. He is stern.

Enrique nods. So do two other immigrants, a Mexican brother and sister, waiting with him. They strip to their underwear.

Across the Rio Grande stands a 50-foot pole equipped with U.S. Border Patrol cameras. In daylight, Enrique has counted four sport utility vehicles near the pole, each with agents. Now, in the darkness, he cannot see any.

He leaves it up to El Tirindaro, a subspecies of smuggler known as a patero because he pushes people across the river on inner tubes by paddling soundlessly with his feet, like a pato, or duck. El Tirindaro has spent hours at this spot studying everything that moves on the other side.

Enrique, 17, tears up a small piece of paper and scatters it on the riverbank. It is his mother’s phone number. He has memorized it. Now the agents cannot use it to locate and deport her. She left him behind in Honduras more than 11 years ago and entered the United States illegally to seek work. In all, Enrique has spent four months trying to find her.

El Tirindaro holds an inner tube. The Mexicans climb on. He paddles them to an island in midstream. He returns for Enrique with the tube.

He steadies it in the water.

Carefully, Enrique climbs aboard. The Rio Bravo, as it is called here, is swollen with rain. Two nights before, it had killed a youngster he knew. Enrique cannot swim, and he is afraid.

El Tirindaro places a plastic garbage bag on Enrique’s lap. It contains dry clothing for the four of them. Then El Tirindaro paddles and starts to push. A swift current grabs the tube and sweeps it into the river. Wind whips off Enrique’s cap. Drizzle coats his face. He dips in a hand. The water is cold.

All at once, he sees a flash of white--one of the SUVs, probably with a dog in back, inching along a trail above the river.

Silence. No bullhorn barks, “Turn back.”

The inner tube lurches along. It is May 21, 2000. Agents will catch 108,973 migrants in this area alone during fiscal 2000. The tube sloshes and bounces. Enrique grips the valve stem. The sky is overcast, and the river is dark. In the distance, bits of lights dance on the surface.

At last, he sees the island, overgrown with willows and reeds. He seizes the limb of a willow. It tears off. With both hands, he lays hold of a larger branch, and the inner tube swings onto the silt and grass. They have crossed the southern channel. On the other side of the island flows the northern channel, even more frightening because it is closer to the United States.

El Tirindaro circles the island on foot and looks across the water. The white SUV reappears, less than 100 yards away. It is moving slowly along the dirt trail, high on the riverbank.

Its roof lights flash red and blue on the water, creating a psychedelic sheen. Agents turn to aim a spotlight straight at the island.

Enrique and the Mexicans dive to the ground face-first. If the agents spot them and lie in wait, it could spell doom for Enrique. He is closer to his mother than ever. Authorities could deport the Mexicans back across the river, but they could send him all the way to Honduras. It would mean starting out for the ninth time.

For half an hour, everyone lies stone-still.

Crickets sing, and water rushes around the rocks. Finally the agents seem to give up. El Tirindaro waits and watches. He makes certain, then returns.

Enrique whispers: Take the others first.

El Tirindaro loads the Mexicans onto the tube. Their weight sinks it almost out of sight. Slowly, they lumber across the water.

Minutes later, El Tirindaro returns. “Get over here,” he says to Enrique. “Climb up.” He has other instructions: Don’t rustle the garbage bag holding the clothes. Don’t step on twigs. Don’t paddle; it makes noise.

El Tirindaro slips into the water behind the tube and kicks his legs beneath the surface. It takes only a minute or two. He and Enrique reach a spot where the river slows, and Enrique grabs another branch. They pull ashore and touch soft, slippery mud.

In his underwear, Enrique stands for the first time on U.S. soil.

Nearly frozen

As El Tirindaro hides the inner tube, he spots the Border Patrol.

He and the three immigrants hurry along the edge of the Rio Grande to a tributary called Zacate Creek.

Get in, El Tirindaro says.

Enrique walks into the creek. It is cold. He bends his knees and lowers himself to his chin. His broken teeth chatter so hard they hurt; he cups a hand over his mouth, trying to stop them. For an hour and a half, they stand in Zacate Creek in silence. Effluent spills into the water from a three-foot-wide pipe close by. It is connected to a sewage treatment plant on the edge of Laredo, Texas. Enrique can smell it.

El Tirindaro walks ahead, scouting as he goes.

At his command, Enrique and the others climb out of the water. Enrique is numb. He falls to the ground, nearly frozen.

“Dress quickly,” El Tirindaro says.

Enrique steps out of his wet undershorts and tosses them away. They are his last possession from home. He puts on dry jeans, a dry shirt and his two left shoes. It has been three days since his right one was stolen, and all he has been able to find is a second left shoe to replace it. He told his mother about it when he called her, but there was no time for her to send any money for a proper pair.

El Tirindaro offers everyone a piece of bread and a soda. The others eat and drink. Enrique is too nervous. Being on the outskirts of Laredo means they are near homes. If dogs bark, the Border Patrol will suspect intruders.

“This is the hard part,” El Tirindaro says.

He runs. Enrique races behind him. The Mexicans follow, up a steep embankment, along a well-worn dirt path, past mesquite bushes and behind some tamarind trees, until they are next to a large, round, flat tank. It is part of the sewage plant.

Beyond is an open space.

El Tirindaro glances nervously to the right and left. Nothing.

“Follow me,” he says.

Now he runs faster. Numbness washes out of Enrique’s legs. It disappears in a wave of fear. They sprint next to a fence, then along a narrow path on a cliff above the creek. They dash down another embankment, into the dry upstream channel of Zacate Creek, under a pipe, then a pedestrian bridge, across the channel, up the opposite embankment and out onto a two-lane residential street.

Two cars pass. Winded, the four scuttle into bushes. Half a block ahead, another car flashes its headlights.

Puffs of clouds

It is a red Chevrolet Blazer with tinted windows. As they reach it, locks click open. Enrique and the others scramble inside. In front sit a Latino driver and a woman. Enrique has met them before, at a house across the river frequented by El Tirindaro. They are part of his smuggling network.

It is 4 a.m. Enrique is exhausted. He climbs onto pillows in back. They are like puffs of clouds, and he feels immense relief. He smiles and says to himself, “Now that I’m in this car, no one can get me out.” The engine starts, and the driver passes back a pack of beer. He asks Enrique to put it into a cooler. The driver pops a top.

For a moment, Enrique worries: What if the driver has too many?

The Blazer heads toward Dallas.

Border Patrol agents pay attention to Blazers and other SUVs. Headlights tilted up mean there are people in the back, weighing down the vehicle, says Alexander D. Hernandez, a supervisor in Cotulla, Texas. Weaving means the load is heavy and causing sway. When the agents notice, they pull alongside and shine a flashlight into the eyes of the passengers. If the riders do not look over but seem frozen in their seats, they are likely to be illegal immigrants.

Enrique sleeps until El Tirindaro shakes him. They are out of Laredo and half a mile south of a Border Patrol checkpoint.

“Get up!” El Tirindaro says. Enrique can tell he has been drinking. Five beers are gone. The Blazer stops. Enrique and the two Mexicans, with El Tirindaro leading, climb a wire fence and walk east, away from the freeway. Then they turn north, parallel to it. Enrique can see the checkpoint at a distance.

Every car must stop.

“U.S. citizens?” agents ask. Often, they check for documents.

Enrique and his group walk 10 minutes more, then turn west, back toward the freeway. They crouch next to a billboard. Overhead, the stars are receding, and he can see the first light of dawn.

The Blazer pulls up.

Enrique sinks back into the pillows. He thinks: I have crossed the last big hurdle. Suddenly he is overwhelmed. Never has he felt so happy.

He stares at the ceiling and drifts into a deep, blissful sleep.

Four hundred miles later, the Blazer pulls into a gas station on the outskirts of Dallas. Enrique awakens. El Tirindaro is gone. He has left without saying goodbye. From conversations in Mexico, Enrique knows that El Tirindaro gets $100 a client. Enrique’s mother, Lourdes, has promised $1,200. Clearly, this is all business, and the driver is the boss; he gets most of the money. The patero is on his way back to Mexico.

Along with fuel, the driver buys more beer, and the Blazer rolls into Dallas about noon. America looks beautiful. The buildings are huge. The freeways have traffic exchanges with double and triple decks. They are nothing like the dirt streets at home. Everything is so clean.

The driver drops off the Mexicans and takes Enrique to a large house. Inside are bags of clothing in various sizes and American styles, to outfit clients so they no longer stand out.

They telephone his mother.

Lourdes, 35, has come to love North Carolina. People are polite. There are plenty of jobs for immigrants, and it seems to be safe. She can leave her car unlocked, as well as her house.

A gray album holds treasures: pictures of Belky, her daughter back home. At 7, Belky wears a white First Communion dress; at 9, a yellow cheerleader’s skirt; at 15, for her quinceanera, a pink taffeta dress and white satin shoes. There are pictures of Enrique too: at 8 in a tank top, with four piglets at his feet; at 13 in the photograph at Belky’s quinceanera, the serious-looking little brother.

Lourdes has not slept. All night, since Enrique’s last call from a pay phone across the Rio Grande, she has been having visions of him dead, floating on the river, his body wet and swollen. She told her boyfriend, “My greatest fear is to never see him again.”

Now a female smuggler is on the phone. The woman says: We have your son in Texas, but $1,200 is not enough. $1,700.

Lourdes grows suspicious. Maybe Enrique is dead, and the smugglers are trying to cash in. “Put him on the line.”

He is out shopping for food, the smuggler says.

Lourdes will not be put off.

He is asleep, the smuggler says.

How can he be both? Lourdes demands to talk to him.

Finally, the smuggler gives the phone to Enrique.

“Sos tu?” his mother asks anxiously. “Is it you?”

“Si, Mami, it’s me.”

Still, his mother is not sure. She does not recognize his voice. She has heard it only half a dozen times in 11 years.

“Sos tu?” she asks again. Then twice more. She grasps for something, anything, that she can ask this boy -- a question that no one but Enrique can answer. She remembers what he told her about his shoes when he called on the pay phone.

“What kind of shoes do you have on?” she asks.

“Two left shoes,” Enrique says.

Fear drains from his mother like a wave back into the sea. It is Enrique. She feels a moment of pure happiness.

She takes $500 she has saved, borrows $1,200 from her boyfriend and wires it to Dallas.

In the house with the clothing, the smugglers wait. From the bags, Enrique puts on clean pants, a shirt and a new pair of shoes. The smugglers take him to a restaurant. He eats chicken smothered in cream sauce. Clean, sated, in his mother’s adopted country, he is happy.

They go to Western Union. But there is no money under his mother’s name, not even a message.

How could she do this?

At worst, Enrique figures, he can break away. Run.

But the smugglers call again.

She says she has sent the money through a female immigrant who lives with her, because the woman gets a Western Union discount. The money should be there under the woman’s name.

Enrique has no time to celebrate. The smugglers take him to a gas station, where they meet another man in the network. He puts Enrique with four migrant men being routed to Orlando, Fla. They stay overnight in Houston, and at midday, Enrique leaves Texas in a green van.

Five days later, Lourdes’ boyfriend gets time off from work to drive to Orlando, where Enrique has been staying with other migrants and waiting for him to arrive. Her boyfriend is handsome, with graying temples and a mustache. Enrique recognizes him from a video that his Uncle Carlos had brought back from a visit.

“Are you Lourdes’ son?” the boyfriend asks.

Enrique nods.

“Let’s go.” They say little in the car, and Enrique falls asleep.

By 8 a.m. on May 28, Enrique is in North Carolina. He awakens to tires crossing highway seams: Click-click. Click-click. “Are we lost?” he asks. “Are you sure we aren’t lost? Do you know where we are going?”

“We’re almost there.”

They are moving fast through pines and elms, past billboards and fields, yellow lilies and purple lilacs. The road is freshly paved. It goes over a bridge and passes cattle pastures with large rolls of hay. On both sides are wealthy subdivisions. Then railroad tracks. Finally, at the end of a short gravel street, some house trailers. One is beige. Built in the 1950s, it has white metal awnings and is framed in tall green trees.

At 10 a.m., after more than 12,000 miles, 122 days and seven futile attempts to find his mother, Enrique, 11 years older than when she left him behind, bounds from the back seat of the car, up five faded redwood steps, and swings open the white door of the mobile home.

To the left, beyond a tiny living room with dark wooden beams, sits a girl with shoulder-length black hair and curly bangs. She is at the kitchen table eating breakfast. He remembers a picture of her. Her name is Diana. She is 9. She was born in California, not long after Lourdes came to the United States, while she lived with a former boyfriend from Honduras.

Enrique leans over and kisses the girl on the cheek.

“Are you my brother?”

He nods. “Where is my mother? Where is my mother?”

She motions past the kitchen to the far end of the trailer.

Enrique runs. His feet zigzag down two narrow, brown-paneled hallways.

He opens a door.

Inside, the room is cluttered, dark. On a queen-size bed, under a window draped with lace curtains, his mother is asleep. He jumps squarely onto the bed next to her. He gives her a hug. Then a kiss.

“You’re here, mi hijo.”

“I’m here,” he says.

“The Odyssey,” an epic poem about a hero’s journey home from war, ends with reunion and peace. “The Grapes of Wrath,” the classic novel about the dust bowl and the migration of Oklahoma farmers to California, ends with death and a glimmer of renewed life.

Enrique’s journey is not fiction, and its conclusion is more complex and less dramatic. But it ends with a twist worthy of O. Henry.

Children like Enrique dream of finding their mothers and living happily ever after. For weeks, perhaps months, these children and their mothers cling to romanticized notions of how they should feel toward each other.

Then reality intrudes.

The children show resentment because they were left behind. They remember broken promises to return and accuse their mothers of lying. They complain that their mothers work too hard to give them the attention they have been missing. In extreme cases, they find love and esteem elsewhere, by getting pregnant, marrying early or joining gangs.

Some are surprised to discover entire new families in the United States--a stepfather, stepbrothers and stepsisters. Jealousies grow. Stepchildren call the new arrivals mojados, or wetbacks, and threaten to summon the Immigration and Naturalization Service to deport them.

The mothers, for their part, demand respect for their sacrifice: leaving their children for the children’s sake. Some have been lonely and worked hard to support themselves, to pay off their own smuggling debts and save money to send home. When their children say, “You abandoned me,” they respond by hauling out tall stacks of money transfer receipts.

They think their children are ungrateful and bristle at the independence they show--the same independence that helped the children survive their journeys north. In time, mothers and children discover they hardly know each other.

At first, neither Enrique nor Lourdes cries. He kisses her again. She holds him tightly. He has played this out in his mind a thousand times. It is just as he thought it would be.

All day they talk. He tells her about his travels: the clubbing on top of a train, leaping off to save his life, the hunger, thirst and fear. He has lost 28 pounds, down to 107. She cooks rice, beans and fried pork. He sits at the table and eats. The boy she last saw when he was in kindergarten is taller than she is. He has her nose, her round face, her eyes, her curly hair.

“Look, Mom, look what I put here.” He pulls up his shirt. She sees a tattoo.

EnriqueLourdes, it says, across his chest.

His mother winces. Tattoos, she says, are for delinquents, for people in jail. “I’m going to tell you, son, I don’t like this.” She pauses. “But at least if you had to get a tattoo, you remembered me.”

“I’ve always remembered you.”

He tells her about Honduras, how he stole his aunt’s jewelry to pay drug debts, how he wanted to get away from drugs, how he ached to be with her.

Finally, Lourdes cries.

She asks about Belky, her daughter in Honduras; her own mother; and the deaths of two brothers. Then she stops. She feels too guilty to go on.

The trailer is awash in guilt. Eight people live here. Several have left their children behind. All they have is pictures. Lourdes’ boyfriend has two sons in Hondruas. He has not seen them in five years.

Enrique likes the people in the trailer, especially his mother’s boyfriend; he could be a better father than his own dad, who abandoned him to start another family.

Three days after Enrique arrives, Lourdes’ boyfriend helps him find work as a painter. He earns $7 an hour. Within a week, he is promoted to sander, making $9.50. With his first paycheck, he offers to pick up $50 of the food bill. He buys Diana a gift: a pair of pink sandals for $5.97. He sends money to Belky and to Maria Isabel Caria Duron, his girlfriend in Honduras.

Lourdes brags to her friends. “This is my son. Look at him! He is so big. It’s a miracle he’s here.”

Whenever he leaves the house, she hugs him. When she comes home from work, they sit on the couch, watching her favorite soap opera, with her hand resting on his arm.

Over time, though, they realize they are strangers. Neither knows the other’s likes or dislikes. At a grocery store, Lourdes reaches for bottles of Coke. Enrique says he does not drink Coke--only Sprite.

He plans to work and make money. She wants him to study English, learn a profession.

He goes to a pool hall without asking permission. She becomes upset.

Occasionally, he uses profanities. She tells him not to. Both remember their angry words.

“No, Mami!” he says. “No one is going to change me.”

“Well, you’ll have to change! If not, we will have problems. I want a son who, when I say to do something, he says OK.”

“You can’t tell me what to do!”

The clash culminates when Maria Isabel telephones collect and her call is rejected because some of the migrants in the trailer do not know who she is.

That was right, Lourdes says; they cannot afford collect calls from just anyone.

Enrique flares and begins to pack.

Lourdes walks up behind him and spanks him hard on his buttocks, several times.

“You have no right to hit me! You didn’t raise me.”

Enrique spends the night sleeping in her car.

In the end, however, their love prevails. Their differences ease.

Enrique and his mother are conciliatory at last. They are living in her trailer home to this day.

More than that, they might be joined by Maria Isabel.

One day, Enrique phones Honduras. Maria Isabel is pregnant, as he suspected before he left. On Nov. 2, 2000, she gives birth to their daughter.

She and Enrique name the baby Katherine Jasmin.

The baby looks like him. She has his mouth, his nose, his eyes.

An aunt urges Maria Isabel to go to the United States, alone. The aunt promises to take care of the baby.

“If I have the opportunity, I’ll go,” Maria Isabel says. “I’ll leave my baby behind.”

Enrique agrees. “We’ll have to leave the baby behind.”

More to Read

Mexican authorities rescue 31 migrants abducted near the texas border.

Jan. 3, 2024

A 100-foot drop, a death-defying ritual: Mexican children learn how to fly

Dec. 20, 2023

Hallucinations, thirst and desperation: How migrants endured 36 days at sea

Dec. 18, 2023

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

World & Nation

Nigeria’s fashion and dancing styles in the spotlight as Harry, Meghan visit its largest city

In progressive Argentina, the LGBTQ+ community says President Milei has turned back the clock

Panama’s next president says he’ll try to shut down one of the world’s busiest migration routes

Thousands of civilians flee northeast Ukraine as Russia presses a renewed border assault

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Luis Enrique is rebuilding his reputation quickly after finally getting PSG to play like a team

PSG’s head coach Luis Enrique reacts from the touchline during the French League One soccer match between Paris Saint-Germain and Le Havre at the Parc des Princes in Paris, Saturday, April 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Thibault Camus)

PSG’s Kylian Mbappe, center, reacts with his teammates after the French League One soccer match between Paris Saint-Germain and Le Havre at the Parc des Princes in Paris, Saturday, April 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Thibault Camus)

PSG’s head coach Luis Enrique stands on th touchline during the French League One soccer match between Paris Saint-Germain and Le Havre at the Parc des Princes in Paris, Saturday, April 27, 2024. (AP Photo/Thibault Camus)

- Copy Link copied

Luis Enrique has managed to rebuild his reputation quickly in his first season at Paris Saint-Germain.

With the French league title already in the bag, PSG now has a chance to win a historic treble of trophies — which would firmly re-establish Enrique as one of the top coaches in Europe after his image was tarnished by an unsuccessful spell with Spain.

PSG wrapped up the French league title with three games to spare this weekend, in one of the most dominant seasons in the league’s history.

The team is on a 26-game unbeaten streak in the league since September. With just one loss in 31 Ligue 1 matches so far, PSG has an unassailable 12-point lead over second-place Monaco.

“I wouldn’t have imagined this scenario going as positively as this,” the 53-year-old Enrique said.

The Spanish coach led Barcelona to nine trophies from 2014 to 2017, including the Champions League title, but his reputation took a big knock during his tenure with Spain’s national team. Spain had just one win in four games at the 2022 World Cup and was eliminated by Morocco in the last 16.

Enrique can put that setback firmly behind him if he manages to also lead PSG to an elusive Champions League title, something the Qatari-backed club couldn’t even achieve when it had Lionel Messi and Neymar playing alongside Kylian Mbappé.

PSG plays at Borussia Dortmund in the first leg of the Champions League semifinals on Wednesday. It has also reached the French Cup final, where it faces Lyon on May 25.

There is no doubt PSG has made huge progress under Enrique’s helm.

PSG also won the French league in the past two seasons, but got knocked out in the last 16 of the French Cup and the Champions League under Christophe Galtier last year, and under Mauricio Pochettino in 2022.

Trophies aside, Enrique showed his leadership skills by successfully navigating the tense relations between Mbappé — who will leave the club at the end of the season — and PSG’s Qatari owners.

Enrique started Mbappé on the bench seven times this season, both to manage the France striker’s playing time and to test his options for next season. The strategy has worked well so far as Mbappé still leads the league with 26 goals — nine more than anyone else — and scored twice in the second leg against Barcelona in the Champions League quarterfinals.

TACTICAL MASTER

PSG owes a lot of its success to Enrique’s tactical shrewdness.

Manuel Ugarte started the season as the team’s holding midfielder, but Enrique noticed that Vitinha was better at playing the ball out from the back than Ugarte, a ball winner by trade. So Enrique switched from using Vitinha as a box-to-box player to deploying him as a deep-lying playmaker in front of the defense. And Vitinha’s vision and passing skills have helped PSG get more control in midfield.

Likewise, Enrique quickly noticed that Lucas Beraldo struggled in the first leg of the Champions League quarterfinal against Barcelona as Robert Lewandowski dragged him all over the pitch. Enrique dropped Beraldo in the second leg to let the more experienced Marquinhos and Lucas Hernandez deal with Lewandowski. PSG won 4-1 to reverse a 3-2 home defeat in the first leg and advance.

Enrique was already known for his tactical flexibility at Barcelona, and has shown the same willingness to adapt at PSG by using different formations.

PSG has played with both a back four and a back three this season, and switched from using a lone striker in some games to two strikers in others.

Those variations helped Enrique rotate the team, make tactical experiments and create different kinds of problems for opponents.

“In order to be able to compete for every trophy, as I have said, you need a really big squad of at least 23 players. That is what we need here, and as the season has progressed, we have seen the importance of those players,” Enrique said.

Players’ versatility has been the key to Enrique’s rotation policy.

Marquinhos, Hernandez and Beraldo have been used as both center backs and fullbacks this season. Carlos Soler and Warren Zaire-Emery are midfielders but had to deputize in the right back position.

Lee Kang-in has played as a winger and as a midfielder. And Enrique even used France winger Ousmane Dembele in the No. 10 position a couple of times.

But perhaps Enrique’s greatest achievement has been to build team chemistry at a club where star players have often seemed more influential than the coaches in the past.

PSG’s repeated failures in the Champions League have usually been due to the fact that the collective performance seemed smaller than the sum of its parts.

By contrast, PSG now looks like a genuine team.

AP soccer: https://apnews.com/hub/soccer

- Description

- Don Francisco Presenta

- Update on the Family

- María Isabel

- Young Adult Version

- Spanish Version

- Spanish Language Reviews

- Praise for Enrique’s Journey

- Reviews of Enrique’s Journey

- Articles about Author

- Articles by Author

- TV Interviews

- Radio Interviews

- Speech Videos

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Speech Topics

- High School

- Middle School

- Enrique’s Journey Common Reads

- Counseling Guides

- How to Help Immigrant Students

- Work By & For Students

- Recommended Movies & Documentaries

- Journalism Instruction

- Interview with Facing History and Ourselves

- Questions for Discussion

- Media Coverage: Children and the Journey North

- Art Inspired by the Book

- Theatrical Play

- Photos of People Who Help

- Photos of Injured Migrants

- Get Involved

- Refugees at our Door

- Kids in Need of Defense [KIND]

- Hope for Honduras

- Esperanza para Honduras

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

LUIS ENRIQUE MOTIÑO PINEDA. Daniel, age 2, 2014. Enrique finally married María Isabel Carias Durón, and they have two children, Katerin Jasmín, age 14, and Daniel Enrique, age 2. Enrique works as a painter during the week, but still sporadically abuses drugs, which he had gotten hooked as an early teen in Honduras.

Feb. 24, 2014 12 AM PT. In the updated version of "Enrique's Journey" released this month, the 16-year-old boy who came northward in search of his mother is now a young man in his twenties ...

Key Facts about Enrique's Journey. Full Title: Enrique's Journey: The Story of a Boy's Dangerous Odyssey to Reunite with his Mother. When Written: 1997-2006. Where Written: Honduras, the United States, Mexico. When Published: 2006. Genre: Non-fiction.

Enrique's Journey: The Story of a Boy's Dangerous Odyssey to Reunite with his Mother was a national best-seller by Sonia Nazario about a 17-year-old boy from Honduras who travels to the United States in search of his mother. It was first published in 2006 by Random House.The non-fiction book has been published in eight languages, and is sold in both English and Spanish editions in the United ...

On October 6, 2002, chapter five of the story, "Enrique's Journey," by Sonia Nazario appeared in the Los Angeles Times.The story was awarded the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for feature writing and ...

About Enrique's Journey. An astonishing story that puts a human face on the ongoing debate about immigration reform in the United States, now updated with a new Epilogue and Afterword, photos of Enrique and his family, an author interview, and more—the definitive edition of a classic of contemporary America Based on the Los Angeles Times ...

Enrique's Journey | Chapter Three: Defeated Seven Times, a Boy Again Faces 'the Beast' 1 / 11 A man carries a raft out of the Rio Suchiate at Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico, a major arrival point ...

July 16, 2014 4:47 PM PT. This six-part series from 2002 chronicles the journey of Enrique, who traveled alone from Honduras as a teenager in search of his mother in the United States. Sonia ...

Enrique's Journey recounts the unforgettable quest of a Honduran boy looking for his mother, eleven years after she is forced to leave her starving family to find work in the United States. Braving unimaginable peril, often clinging to the sides and tops of freight trains, Enrique travels through hostile worlds full of thugs, bandits, and ...

Enrique's Journey recounts the unforgettable quest of a Honduran boy looking for his mother, eleven years after she is forced to leave her starving family to find work in the United States. Braving unimaginable peril, often clinging to the sides and tops of freight trains, Enrique travels through hostile worlds full of thugs, bandits, and ...

From the moment Enrique crossed into Mexico, he was hunted down like an animal by bandits alongside the tracks, gangsters who control the train tops, and corrupt cops. Today, the most feared narco ...

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers! A Note for Teachers Originally written as a newspaper series for the Los Angeles Times, Enrique's Journey tells the true story of a Honduran boy's journey to find his mother in America. As a literary text, the work lends itself easily to the study of primary elements: plot, setting, character, theme, etc. Beginning in ...

She enters through a rat-infested Tijuana sewage tunnel and makes her way to Los Angeles. She moves in with a Beverly Hills couple to take care of their 3-year-old daughter. Every morning as the ...

Enrique's journey tells the larger story of undocumented Latin American migrants in the United States. His is an inspiring and timeless tale about the meaning of family and fortitude that brings to light the daily struggles of migrants, legal and otherwise, and the complicated choices they face. The issues seamlessly interwoven into this ...

She is best known for "Enrique's Journey," her story of a Honduran boy's struggle to find his mother in the U.S. Published as a series in the Los Angeles Times, "Enrique's Journey" won the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing in 2003. It was turned into a book by Random House and became a national bestseller.

Today, more illegal immigrants use smugglers to get past the security measures (and incredible dangers) of the journey into the United States. In conclusion, ... The story that has produced this book, Enrique's Journey, is one that humanizes the individuals involved. But in doing so it also shows how their choices were ultimately shaped by ...

Reporter: Jody HammondPhotographer: Michael PeakEditor: Clint Burkett Enrique's journey unveils an exclusive look at the Pulitzer Prize-winning photographs c...

Sonia Nazario '82 spoke about her Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Enrique's Journey: The Story of a Boy's Dangerous Odyssey to Reunite with his Mother, at the '62 Center in September as part of the Williams Reads program. Hers is the first Williams Reads book written by an Eph. You can listen to a podcast about her experiences researching and writing the book, as well as her thoughts on ...

Enrique's mother, Lourdes, has promised $1,200. Clearly, this is all business, and the driver is the boss; he gets most of the money. The patero is on his way back to Mexico.

Luis Enrique has managed to rebuild his reputation quickly in his first season at Paris Saint-Germain. With the French league title already in the bag, PSG now has a chance to win a historic treble of trophies — which would firmly re-establish Enrique as one of the top coaches in Europe after his image was tarnished by an unsuccessful spell with Spain.

Belky - enriquesjourney.com. Belky. Sonia visited Enrique's sister Belky , seen here with her husband and two sons, in the summer of 2016. They had just finished expanding their tiny home to accommodate their growing family. Enrique's sister, Belky, and Sonia in Belky's home, 2014. Belky with Jonathan, 2014. Enrique's sister Belky at ...