Registered Nurse RN

Registered Nurse, Free Care Plans, Free NCLEX Review, Nurse Salary, and much more. Join the nursing revolution.

Protrusion, Retrusion, and Excursion Anatomy

In this anatomy lesson, I’m going to demonstrate protrusion, retrusion, and excursion , which are special body movement terms in anatomy that refer to forward (anterior), backward (posterior), or side to side movements.

Protrusion in Anatomy

Protrusion refers to the movement of a structure in an anterior (forward) direction. In fact, the word protrude means “projecting something forward.”

I call protrusion the kissing movement because it occurs when you pucker your lips like you’re going to give someone a kiss or stick out your tongue. Moving the mandible (lower jaw) forward is also an example of protrusion.

Retrusion in Anatomy

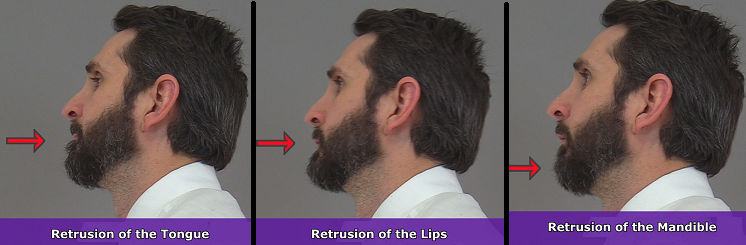

Retrusion is the opposite of protrusion. It refers to the movement of a structure in a posterior, or backward, direction. Putting your tongue back in your mouth, moving the lips back, or moving the mandible back are all examples of retrusion in anatomy.

Excursion in Anatomy

Finally, we have excursion , which refers to the side-to-side movement of the lower jaw (mandible). If you’ve ever heard of a character named Ernest P. Worrell, then you’ve definitely seen the excursion movement. He’s the character in those movies such as Ernest Goes to Camp, Ernest Goes to Jail, etc. When Ernest saw something nasty, he’d move his jaw back and forth and say, “Ewwww.”

Excursion can occur in either direction, and anatomists use directional terms to specify the type of excursion. When the mandible moves to either the left or right, it’s moving away from the body’s midline, so it’s called lateral excursion . When the mandible moves closer to the midline of the body, it’s called medial excursion .

Protrusion and Retrusion vs Protraction and Retraction

What about protraction and retraction ? Some anatomy textbooks will refer to the forward movement of the mandible, lips, or tongue as protraction (instead of protrusion), and the backward (posterior) movement will be called retraction (instead of retrusion). The terms are sometimes used interchangeably, so use whatever method your anatomy professor suggests (they give you the grade, not me!).

However, some anatomists today use protraction and retraction to refer almost exclusively to the scapulae, as it is a combined movement (protraction is anterolateral, and retraction is posteromedial). In contrast, protrusion and retrusion are more of an anterior/posterior movement. Then again, some anatomists prefer not to use protraction and retraction at all, even when describing shoulder blade movement.

Protrusion, Retrusion, and Excursion in Healthcare

Healthcare professionals use protrusion, retrusion, and excursion when documenting, performing assessments on patients, or treating disorders. For example, in her head-to-toe assessment , Nurse Sarah asked me to stick out my tongue (an example of protrusion), to assess cranial nerve twelve .

In addition, something called a mandibular protrusion test (MPT) is sometimes used by anesthesiologists to predict difficult airways in patients.

Free Quiz and More Anatomy Videos

Take a free protrusion vs retrusion quiz to test your knowledge, or review our protrusion vs retrusion video . In addition, you might want to watch our anatomy and physiology lectures on YouTube, or check our anatomy and physiology notes .

Please Share:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Disclosure and Privacy Policy

Important links, follow us on social media.

- Facebook Nursing

- Instagram Nursing

- TikTok Nurse

- Twitter Nursing

- YouTube Nursing

Copyright Notice

- Media Library

- Encyclopedia

- Universities

Unlock with Premium

- Dynamic occlusion: lateral excursion

The dynamic occlusion is the contact that teeth make during movements of the mandible - when the jaw moves side to side, forward, backward or at an angle. In dynamic occlusion, the contacts of the teeth are not points as in static occlusion, but they are described with lines.

- Dental occlusion

- Occlusal relationship

- Temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

- Joint capsule and ligaments of TMJ

- Movements of TMJ

- Static occlusion: centric occlusion

- Occlusion concepts: centric relation

- Angle's classification

- Angle's classification: Class I

- Angle’s classification: Class II, Division 1

- Angle's classification: Class II, Division 2

- Angle's classification: Class III

- Dynamic occlusion: canine guidance

- Dynamic occlussion: protrusion

- Curve of Spee

- Curve of Wilson

- Sphere of Monson

English focus texts

- Phantom heads (Dental manikins)

- Bewegungsablauf

- Exkursionsbewegung

Want to give it a try ...

... or need professional advice? Get in touch with us or click Contact .

Word of the day

Focus text of the month.

- Folge uns auf

- google plus

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Anatomy, occlusal contact relations and mandibular movements.

Sunthosh Sivam ; Philip Chen .

Affiliations

Last Update: June 5, 2023 .

- Introduction

The mandible, which holds the lower teeth, comprises the majority of the lower third of the maxillofacial skeleton and is of utmost functional importance. Complex mandibular movements are afforded by the masseter, temporalis, medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid muscles, and temporomandibular joints. [1] Given that the maxilla is stationary, mastication is dependent on mandibular movement. In certain populations, masticatory function related to dental status is a significant determinant of nutritional status. Being an edentulous geriatric patient without complete dentures was shown to be an independent risk factor for malnutrition. [2] This suggests the importance of functional occlusion.

Occlusion is the articulation between the mandibular and maxillary dental arch. Static and dynamic occlusal relationships can be described in many ways. [3] [4] Understanding the occlusal contact relationship impacts the providers' ability to design and place dental implants, implement orthodontic braces, fit dentures, re-establish masticatory function, and restore a patient’s native bite after maxillofacial trauma.

- Structure and Function

The mandible consists of a body, rami, coronoid processes, and condylar processes. The mandible can be further subdivided into the angle where the ramus transitions to the body, the body, the parasymphysis located anterior to the mental foramen, and the midline symphysis. Mobility in the mandible allows for its participation in mastication and occlusion. [5] The muscles of mastication contribute to the mandible's complex movements and include the temporalis, masseter, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid. [6] There are primarily 6 types of mandibular movement, including opening, closing, rightward jaw translation, leftward jaw translation, protrusion, and retrusion. Variability in jaw movement allows for mastication of different textures and consistencies.

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

The temporomandibular joint is the junction of the mandible and the temporal bone. These are synovial joints, each with an upper and lower compartment divided by an intra-capsular disc. The mandibular condyle articulates with the intra-capsular disc and remains in the mandibular fossa at rest when the jaw is closed. The condyle follows the articular eminence forward during jaw opening.

Condylar movements during mastication are complex. In total, condylar actions within the temporomandibular joints have 3 basic movements: spin, roll, and slide. Spin describes the condylar head twisting about a vertical axis within the capsule. Roll is the condylar head rocking back and forth with the central portion maintaining contact with the intra-capsular disc. Slide refers to the translation of the condylar head relative to the intra-capsular disc.

Intricate movements within the temporomandibular joint translate to mandibular movements needed for mastication. To allow maximal mouth opening, the condyles move downward and forward over the articular eminence. The closing force begins with the condyle ipsilateral to the food bolus moving back into the mandibular fossa upwards and posteriorly to a position lateral from resting. Through closing, the ipsilateral condyle shifts medially while the contralateral condyle moves upward, posteriorly, and laterally.

Maxillary and Mandibular Dental Arch

The permanent, succedaneous teeth in adults consist of 16 teeth in the maxilla and 16 teeth in the mandible. The universal numbering system for permanent teeth assigns numbers to each tooth from 1 to 32. Tooth #1 is the right maxillary third molar followed sequentially by numbers 2-15 across the maxilla until reaching the left maxillary third molar, tooth #16. Numbering continues down to the mandible, with tooth #17 being the left mandibular third molar followed by 18-31 proceeding sequentially across the mandible until reaching the right mandibular third molar, which is tooth #32. [7] [8] There are alternative numbering systems.

Adult dentition consists of 2 central incisors, 2 lateral incisors, 2 canines, 2 first premolars, 2-second premolars, 2 first molars, 2-second molars, and 2 third molars, both in the maxilla and mandible. The teeth are secured within the alveolar ridges of the maxilla and mandible. Dentition, whether native or restored, is integral to masticatory function. [9]

Dental Occlusal Anatomy

The following 5 surfaces of the crown of a tooth allow for discussion of occlusal contacts: [8]

- Facial: oriented toward the lips or teeth and referred to as labial for incisors/canines or buccal for premolars/molars

- Palatal/Lingual: oriented towards the palate for the maxilla and the tongue for the mandible

- Mesial: oriented toward the midline

- Distal: oriented away from the midline

- Occlusal: oriented toward the upper or lower jaw depending on the mandible versus the maxilla

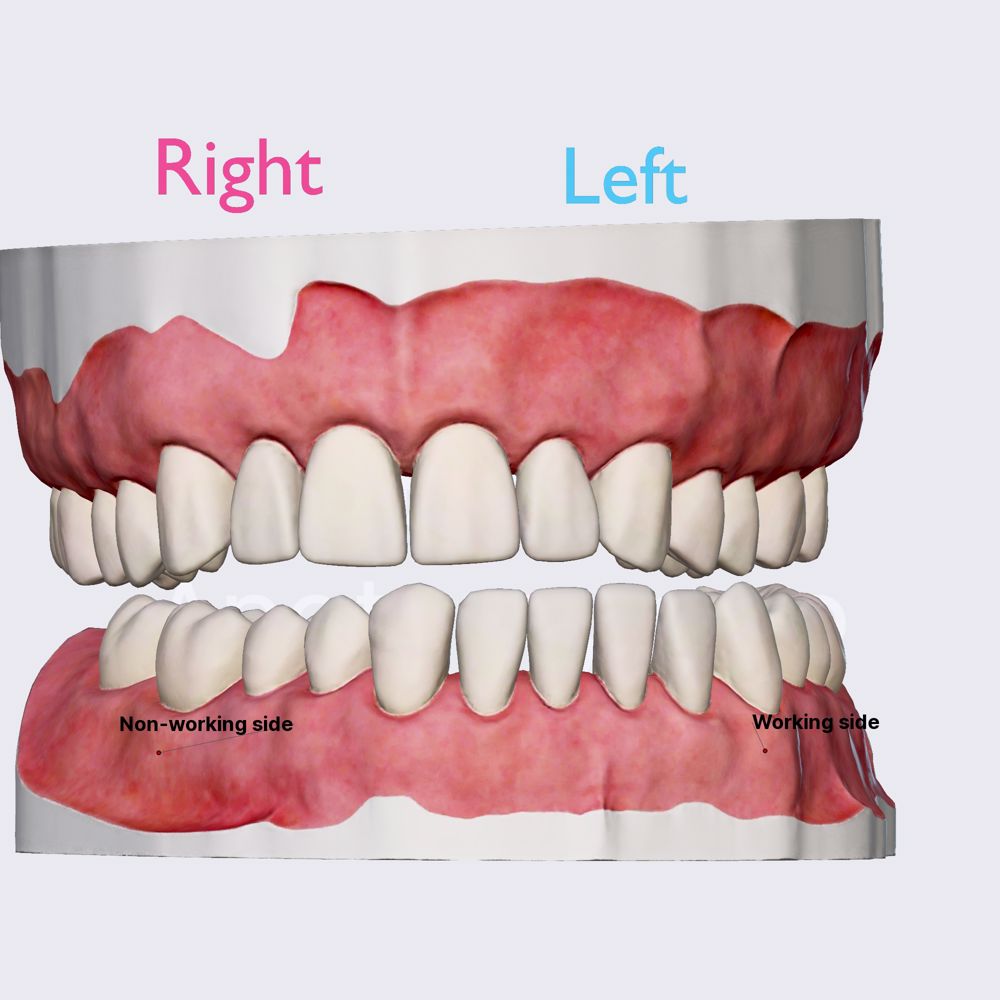

Tooth cusps function to guide erupting teeth into appropriate occlusion with periodontal stimulation informing neural reflexes for jaw closure and mastication [1] . The maxillary palatal cusps and the mandibular facial cusps comprise the centric cusps involved in centric occlusion (discussed below). In contrast, the maxillary buccal cusp and the mandibular lingual cusps guide the mandible during the lateral excursion.

When in occlusion, a lateral view shows a convexity in the maxillary occlusal surface interdigitating with a concavity in the mandibular occlusal surface. The occlusal curve is called the Curve of Spee. Extending the curve while maintaining its arc into a circle centered at the glabella creates the Curve of Monson. In a coronal plane, the mandibular posterior dentition is characterized by a lingual incline, and a buccal incline characterizes the maxillary posterior dentition. The coronal occlusal curve in the posterior dentition is called the Curve of Wilson. [10] Maintaining these characteristic occlusal curves is imperative to the practice of dental implants and denture design/fitting.

Mandibular Movements and Dynamic Occlusal Contacts

The sophisticated movements of the mandible impacting dynamic occlusal contacts are a combination of the 6 primary mandibular movements as well as the condylar movements discussed above. Posselt published his seminal work in the mandibular movement in 1952, including Posselt’s envelope of motion. This depicts the movement of the mandible in a sagittal plane. When the condyle is superior and anterior within the glenoid fossa, the mandible is maximally retruded. In this condyle position, the mandibular opening is referred to as centric relation, and this depends on the rolling (hinge) movement facilitated by the lower synovial cavity in the TMJ. Opening beyond this is dependent on the sliding (translational) movement of the upper synovial TMJ cavity. The first occlusal contact upon mandibular closing, when in centric relation, is referred to as centric occlusion. This is followed by the teeth sliding into the intercuspal position, where maximal intercuspal contacts are made in the occlusion. The Envelope of Motion's anterior arc illustrates mandibular movement into occlusion and opening when the mandible is maximally protruded.

For lateral movement, the mandible is designated into working and non-working sides. The side that the mandible is moving toward is the working side, and that condyle moves laterally. The amount of movement laterally in the condyle is referred to as the Bennett movement. On the non-working side, the lateral movement necessitates downward, inward, and forward positioning of the condyle. The difference between a sagittal plane established through the condyle at rest and a line through the lateral movement's non-working condyle is the Bennett angle, the average being 7.5 degrees. [1] [4]

The first branchial arch gives rise to Meckel's cartilage. On the lateral aspect of Meckel’s cartilage, the mandible starts as two halves, with each half developing an ossification center in the sixth to seventh week of intrauterine development. The ossification centers develop into what will eventually be the symphysis, body, angle, and ramus of the mandible. Separately, cartilage clusters form within the connective tissue, eventually ossify into coronoid and condylar processes.

The two ossified right and left halves of the mandible remain separated by connective tissue until closer to birth when small mental bone(s) (1 or 2) ossify. These mental bones ultimately fuse with the mandible creating a mental protuberance and the unified mandibular bone. [11]

Mesenchymal cells from the first branchial arch give rise to the muscles of mastication. [8]

Odontogenesis is the formation of teeth. The deciduous or baby teeth develop at 6 to 8 weeks gestation, whereas succedaneous teeth develop at 20 weeks. The ectoderm forms the dental enamel, while the ectomesenchyme (neural crest-derived) forms the dentin, cementum, periodontal ligament, and pulp. Placodes represent invaginations of primary dental lamina within the mandibular and maxillary arches beginning the process of tooth formation. Tooth buds form from the placodes, and the tooth buds develop into teeth. [11]

- Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The endosteal blood supply of the mandible is derived from the external carotid artery. The mandibular ramus, condyle, and coronoid have a blood supply from the intramedullary ascending artery (from the inferior alveolar artery), a direct branch of the maxillary artery pterygoid osteomuscular branches. The inferior alveolar artery supplies the mandibular angle and body. Finally, the mandibular symphysis has a rich blood supply consisting of contributions of the submental artery from the facial artery, the sublingual artery from the lingual artery, and the incisive artery from the inferior alveolar artery. [12]

The maxillary artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, branches into the anterior, middle, and posterior superior alveolar arteries providing a blood supply to the maxillary dentition. [8]

The oral cavity primarily has lymphatic drainage to cervical lymph nodes in levels I (submental and submandibular), II (upper internal jugular chain), and III (middle internal jugular chain). [13]

The trigeminal nerve is the 5 and largest cranial nerve. There are three branches of the trigeminal nerve including: ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3). [14] The V2 and V3 divisions are the most relevant for occlusal contact relationships and mandibular movements.

The trigeminal nerve's maxillary division exits the skull base via the foramen rotundum, traverses the pterygopalatine fossa, enters the inferior orbital fissure, and ultimately gives rise to the inferior orbital nerve. This nerve is the origin of the anterior branch of the superior alveolar nerve providing sensation to the anterior hard palate, incisors, and canines. For the molars and posterior two-thirds of the palate, sensation comes from the greater palatine nerves arising from the maxillary nerve. [8]

The mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve exits the skull base via the foramen ovale. The anterior branch provides motor innervation to the muscles of mastication. The posterior branch provides sensory innervation via the long buccal nerve, inferior alveolar nerve (IAN), and the lingual nerve. The IAN provides sensory innervation for mandibular molars and premolars. A small branch of the IAN, the incisive nerve, branches just before the IAN exits the mental foramen becoming the mental nerve. The incisive nerve provides sensation to the mandibular canines and incisors. [8] [11]

The muscles of mastication are also responsible for occlusion, given that they are the predominant mobilizers of the mandible.

Muscles of Mastication [6] [15]

Muscle Origin

Suprahyoid Muscles

The suprahyoid muscles contribute to mandible depression (jaw opening). These include the digastric, stylohyoid, mylohyoid, and geniohyoid muscles. [16]

- Physiologic Variants

Variation in static occlusion seen in the general population can be further described using various classifications. In 1899, Edward Angle introduced his classification of occlusion. [17] This system is based on normal occlusion being determined by the relationship between the maxillary and mandibular first molar as below.

Angle’s Classifications [3]

Class Description

There are variations in native occlusion in the population. 52% of the population is Angle’s class I. While 26.2% are classified as Angle class II and 2.6% being Angle’s class III. This classification system is imperfect, leaving 21% of the population not clearly falling into any Angle classes. [17]

Transverse and vertical relationships between maxillary and mandibular dentition can be described as well.

Lingual-labial/buccal Relationship [3]

Designation Description

Vertical Relationship [3]

Overjet differs from overbite as overjet is the measure of how far anterior the maxillary dentition is in front of the mandibular dentition. [18]

- Surgical Considerations

Orthognathic surgery repositions the maxilla, the mandible, or both. There are numerous indications for orthognathic surgery, including obstructive sleep apnea, Angle’s class II occlusion, Angle class III occlusion, canting of the occlusal plane, aesthetic considerations, and an open bite, among others. A LeFort I osteotomy for the maxilla and bilateral sagittal split osteotomies for the mandible are the mainstays for modern orthognathic surgery. With both the maxilla and mandible manipulated, there is an opportunity to dramatically change a patient’s occlusion. For this reason, dental modeling is imperative to the process, whether done with traditional stone model surgery or virtual surgical planning. [19] [20]

Maxillofacial trauma treatment, including mandibular and LeFort midface fractures, is founded upon pre-traumatic occlusion restoration. Some fracture patterns, particularly in the mandible, resulting in predictable malocclusions. For example, a condylar or subcondylar fracture reduces the vertical height of the mandible, causing premature contact of the ipsilateral posterior dental arch. An anterior open bite characterizes a bilateral condylar fracture because of these dimensional changes. [3]

Mobility of the mandible and/or the maxilla can create complex clinical situations in which occlusion can be altered adversely. Maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) is used intraoperatively to re-establish a patient’s occlusion. This can be achieved using Erich arch bars, inter-maxillary fixation screws, or rapid maxillomandibular fixation systems, among other techniques. With native occlusion secured using MMF, the midfacial fractures and/or mandibular fractures can be reduced and internally fixated. [16] [21] In this way, the occlusion is the foundation of the repair.

Mandibular movement can influence forces surrounding mandibular fractures. The suprahyoid musculature and bite force puts downward anterior pressure on the mandible. The masseter, temporalis, and pterygoid muscles pull the posterior mandible upward. These opposing forces can reduce some (favorable) fractures and displace other (unfavorable) fractures. [16]

- Clinical Significance

Occlusal contact relations are between the maxillary and mandibular dental arches. The quality of these contacts allows for efficient mastication. Nutritional status is dependent on the dental status of a patient, as prior literature has shown. [2] Mastication is reliant on mandibular movements that can be complex, requiring coordination between temporomandibular joints and the muscles of mastication.

There are many ways to examine the quality of occlusion, and this is exemplified when considering dental implants or denture design. In maxillofacial trauma, occlusion can be altered from the trauma itself or suboptimal management of fractures. Keeping the dental occlusion as the foundation for these repairs prevents long-term malocclusion. [3] In other cases, malocclusion can be developmental and adversely impact cosmesis, which is the case for some patients seeking orthognathic surgery. [20]

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Primary Dentition Occlusal Surfaces, incisors, canine, molar, maxilla, mandible StatPearls Publishing Illustration

Primary dentition: occlusal surfaces StatPearls Publishing Illustration

Disclosure: Sunthosh Sivam declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Philip Chen declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Sivam S, Chen P. Anatomy, Occlusal Contact Relations And Mandibular Movements. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Integrated actions of masticatory muscles: simultaneous EMG from eight intramuscular electrodes. [Anat Rec. 1977] Integrated actions of masticatory muscles: simultaneous EMG from eight intramuscular electrodes. Vitti M, Basmajian JV. Anat Rec. 1977 Feb; 187(2):173-89.

- Occlusion of artificial teeth in complete dentures: population-based analysis. [Int J Comput Dent. 2018] Occlusion of artificial teeth in complete dentures: population-based analysis. Kordaß B, Quooß A, John D, Ruge S. Int J Comput Dent. 2018; 21(1):9-15.

- Relationships between the size and spatial morphology of human masseter and medial pterygoid muscles, the craniofacial skeleton, and jaw biomechanics. [Am J Phys Anthropol. 1989] Relationships between the size and spatial morphology of human masseter and medial pterygoid muscles, the craniofacial skeleton, and jaw biomechanics. Hannam AG, Wood WW. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1989 Dec; 80(4):429-45.

- Review A possible biomechanical role of occlusal cusp-fossa contact relationships. [J Oral Rehabil. 2013] Review A possible biomechanical role of occlusal cusp-fossa contact relationships. Wang M, Mehta N. J Oral Rehabil. 2013 Jan; 40(1):69-79. Epub 2012 Aug 7.

- Review [Occlusal schemes of complete dentures--a review of the literature]. [Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim (199...] Review [Occlusal schemes of complete dentures--a review of the literature]. Tarazi E, Ticotsky-Zadok N. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim (1993). 2007 Jan; 24(1):56-64, 85-6.

Recent Activity

- Anatomy, Occlusal Contact Relations And Mandibular Movements - StatPearls Anatomy, Occlusal Contact Relations And Mandibular Movements - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 13 March 1999

tooth surface loss

Occlusion and splint therapy

- N J Capp 1 , 2

British Dental Journal volume 186 , pages 217–222 ( 1999 ) Cite this article

9201 Accesses

30 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Control of occlusal contacts is important to the success of restorative dentistry. Tooth surface loss can contribute to a loss of stability in the occlusion. An occlusal splint is often part of pre-restorative management and can also have a valuable role in protecting both teeth and restorations from excessive loads and further wear.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nicotine pouches: a review for the dental team

Black staining: an overview for the general dental practitioner

Comparative efficacy of a hydroxyapatite and a fluoride toothpaste for prevention and remineralization of dental caries in children

The first two articles in the series concentrated on the aetiology and presentation of tooth surface loss. This paper begins to look at its consequences. Tooth wear can be considered pathological if the degree of wear exceeds the level expected at any particular age. Tooth surface loss affecting the functional surfaces creates difficulties for the restorative dentist and may affect the stability of the occlusion. The first part of this article discusses the importance of occlusal stability and the possible consequences when it is lost. The second part is devoted to the role of occlusal appliances in protecting teeth from wear and in some aspects of the pre-restorative management of tooth surface loss.

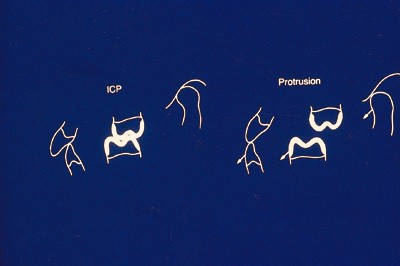

The occlusion

Most functional (chewing) and parafunctional (bruxing and clenching) movements of the mandible take place around the intercuspal position (ICP). This is defined as the mandibular position in which maximum intercuspation of the teeth occurs. Functional movements result in brief contacts between maxillary and mandibular teeth, usually toward the end of the masticatory cycle. However, parafunctional activity may produce prolonged periods of forceful tooth contact.

In 90% of the population maximum intercuspation occurs slightly forward from the retruded position of the mandible to the maxilla. However, contact between opposing teeth and the resultant proprioceptive response guides the mandible repeatedly into the habitual ICP, wherever it may be.

Should a patient exhibit parafunctional activity, it becomes increasingly important that there are enough opposing posterior teeth to provide stable ICP contacts, so that the forces produced during parafunction are distributed over a wide area and in the most favourable direction.

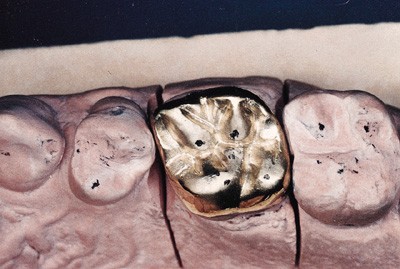

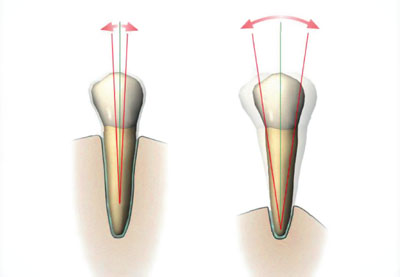

Stable ICP contacts are provided by natural or restored surfaces which have appropriately steep cuspal anatomy ( fig. 1 ). Contact either between the tips of supporting cusps and opposing fossae, or three points surrounding each supporting cusp tip and the ridges surrounding the opposing fossa (tripodisation), provide stable ICP contacts which direct occlusal forces axially.

Restorations with adequately steep cusps provide occlusal stability in ICP while discluding the lateral and protrusive movements

They will also, in conjunction with the proximal contacts of adjacent teeth, stabilise the positions of individual teeth and also of the mandible in ICP. If ICP contacts are unstable, tilting and tipping of teeth are more likely particularly in the absence of an intact arch. This will cause further loss of stable ICP contacts and increase the likelihood of interferences occurring between the posterior teeth during lateral and protrusive movements.

In order to reduce the potentially harmful lateral forces produced by bruxing on interferences between posterior teeth, it is desirable for a patient to possess adequate anterior guidance. Contact between opposing teeth, preferably the canines in lateral excursion and the central incisors in protrusion, discludes the posterior teeth as soon as the mandible moves from ICP ( fig. 1 ). This occlusal scheme most importantly reduces the number of tooth contacts occurring outside ICP. There is some evidence that this alters the proprioceptive feedback to the central nervous system which in turn reduces the level of activity in the masticatory muscles, 1 , 2 although this view is hard to support on scientific grounds. However, in simple practical terms it is very much easier to make restorations in the presence of an adequately steep, immediate disclusion, provided by a small number of teeth near the front of the mouth. 3

How may occlusal stability be maintained or lost?

Most restorations are made to conform to a patient's existing ICP. For this to be an appropriate form of treatment ICP must be stable and the occlusal anatomy of all restorations must be carefully shaped to reproduce correct contacts. In addition, the restorative materials used should be easy to manipulate to produce the necessary occlusal contacts, and exhibit similar wear characteristics to enamel or to opposing restorations. This will reduce the chance of differential wear and increase the likelihood of stable contacts being maintained long-term. Gold ( fig. 2 ) is still the most suitable material based upon these criteria, while amalgam remains the plastic material of choice for posterior teeth. The use of composite resin (direct or indirect) or occlusal porcelain to restore large areas of multiple occlusal surfaces should be avoided in patients prone to parafunction and those with restricted anterior guidance. The difficulty in providing stable contacts and the surface hardness of these materials may result in increased tooth surface loss in the opposing arch ( fig. 3 , 4 ). The careful use of occlusal porcelain and composite resin is less harmful in individuals who possess immediate disclusion of their posterior teeth and do not parafunction.

Gold still provides the best means of restoring occlusal stability

A 3-unit fixed prosthesis with inadequate occlusal form and inappropriate choice of materials for the articulating surfaces

Tooth surface loss because of the abrasive effect of the porcelain guidance surfaces on opposing teeth

Loss of stable contacts may also occur because of tooth surface loss caused by acid erosion or parafunction between unrestored or similarly restored surfaces. Loss of cusp height and definition, broadening areas of ICP contact, combined with a shallowing of the anterior guidance, reduces stability and increases the chances of interferences in lateral or protrusive movements, causing increased and less favourable stress distribution in the teeth affected.

Loss of occlusal stability may result in the repeated fracture of restorations and teeth, increased mobility and drifting, particularly of the upper anterior segment. Traditionally, it has also been held to potentially have other long-term effects on the structure and function of the temporomandibular joints, 4 , 5 although such assertions are increasingly open to question. In the presence of any of these signs of loss of occlusal stability, it sometimes becomes necessary to reorganise the patient's occlusion creating a new and stable ICP at the retruded position of the mandible. There is little reason to choose the retruded position other than because of 'prosthetic convenience'. In the absence of a stable ICP, the retruded position is the only relationship of mandible to maxilla which can be repeatedly and consistently recorded and has been shown to be physiologically acceptable. It is also the maxillo-mandibular relationship to which the mandible will return when not prevented from doing so by interfering tooth contacts. It may therefore be used as the reference position in which the new restorations will intercuspate when re-organising the occlusion.

The rationale and indications for occlusal splints

An occlusal splint is a removable appliance covering some or all of the occlusal surfaces of the teeth in either the maxillary or mandibular arches. The ideal occlusal splint is made from laboratory-processed acrylic resin which should cover the occlusal surfaces of all the teeth in one arch. It should provide even simultaneous contacts on closure on the retruded axis with all opposing teeth and anterior guidance causing immediate disclusion of the posterior teeth and splint surface outside ICP.

The splint provides the patient with an ideal occlusion with posterior stability and anterior guidance. It will disrupt the habitual path of closure into ICP by separating the teeth and removing the guiding effect of the cuspal inclines. It causes an immediate and pronounced relaxation in the masticatory muscles, 6 which will eventually result in the mandible repositioning and closing in the retruded position uninterfered with by the teeth.

In order to achieve this muscle relaxation and mandibular repositioning the occlusal surface of the splint is flat and without indentations so as not to hold or guide the mandible into any predetermined position. The only exception to this is the area lateral to the canine and anterior to the incisor ICP contacts which is gently ramped to provide anterior guidance. To achieve muscle relaxation and repositioning of the mandible, the splint ideally must be worn continuously, failure to do so will result in an increase in masticatory muscle activity. 7 , 8 As the mandible repositions it is necessary to adjust the splint frequently to maintain even contact and disclusion. 9 However, continuous wear is often not compatible with the patient's daily activities. Wear at night and also if possible in the evenings will achieve the same result but more slowly.

Uses of splints

The use of an appropriate occlusal splint may be indicated in the following circumstances:

Prevention of tooth surface loss

Patients who are prone to nocturnal bruxism should routinely wear occlusal splints at night. The splint may reduce their parafunctional activity while it is being worn but as soon as it is removed masticatory muscle activity will resume its increased levels. 6 Whether or not bruxing is continuing can be monitored by observing wear facets created on the splint surface. Even if parafunction continues the intervening splint will prevent damage to the teeth. It is important to motivate patients to wear their splints by stressing the long-term consequences of them not doing so.

Management of mandibular dysfunction

Many studies have shown that an occlusal splint may be beneficial in reducing the pain experienced in mandibular dysfunction. 8 Various theories have been put forward to explain the mechanism involved. One of the more common theories is that in lowering masticatory muscle activity, a splint will effectively reduce the build-up of metabolic waste products which may result in restricting muscle pain and spasm. While there is no doubt that many patients suffering from dysfunction who are treated with occlusal splints, do show a significant decrease in pain levels, it is far from clear that the therapeutic effect of the splint is responsible. 10 It is possible that a significant part of this improvement is achieved through the placebo effect (although there is some evidence that occlusal treatment with a splint does have a truly therapeutic effect 11 , 12 ). Because of the difficulties dentists may experience in diagnosing the source of a patient's facial pain and the doubts which exist over the therapeutic effect of occlusal treatment, it is advisable to carry out only reversible occlusal treatment on such patients (splint therapy, not occlusal equilibration).

Pre-restorative stabilisation

The first part of this paper described the importance of occlusal stability and introduced the concept of reorganising the occlusion to create a new and stable ICP at the retruded position when stability is absent. When conforming to the existing ICP the maxillo-mandibular relationship to which restorations are made is easily and accurately determined by the intercuspation of the teeth. When reorganising it is necessary to locate and record the retruded position of the mandible and then mount both diagnostic and working casts on an articulator in this relationship. In the absence of stable ICP contacts this position is determined solely by the temporomandibular joints and associated neuromuscular system. It is essential that the patient's masticatory system is free from dysfunction, either internal derangement or extra-capsular muscle dysfunction, in order that a correct and reproducible retruded position can be recorded. A consistent position must be recorded before embarking upon restorative treatment. If not, it is likely that changes in the occlusal relationship may occur following tooth preparation and temporisation, or cementation of the new restorations. When reorganising the occlusion it is essential to precede restorative procedures with a period of splint therapy to ensure that a stable relationship has been achieved.

Creating space to restore worn anterior teeth

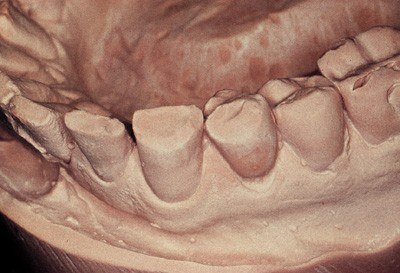

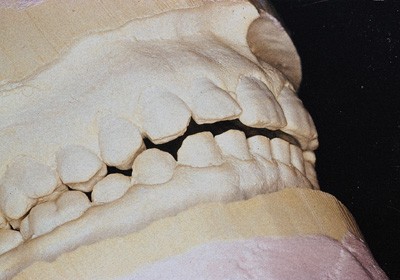

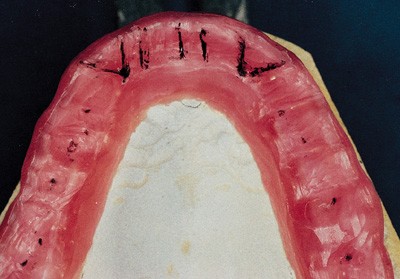

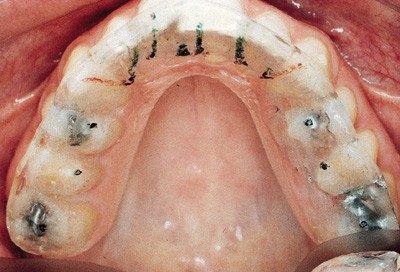

Figures 5 and 6 show a patient before and after splint therapy. At initial examination ( fig. 5 ) the patient requested restoration of severely worn mandibular anterior teeth. It appeared that both ICP and the retruded position were coincident and that no space was available to correctly restore these teeth. After 1 month of wearing an occlusal splint ( fig. 6 ), the mandible had repositioned posteriorly into a stable retruded position. This created space to enable the worn teeth to be properly restored. This repositioning occurred because the pre-existing discrepancy between RCP and ICP had been hidden by the patient's neuromuscular system.

The intercuspal position showing contact between worn mandibular incisal edges and the opposing teeth

One month of occlusal splint therapy resulting in posterior repositioning of the mandible

Protection of new restorations from parafunction

The aetiology of parafunction is largely stress-related. It is likely that patients will continue to brux and clench after restoration of worn teeth. It is highly advisable for them to wear a post-restorative splint to protect their new restorations from damage. This should be made clear to the patient before treatment begins.

Types of occlusal splint — advantages and disadvantages

Many types of occlusal splint have been advocated. They may be full or partial occlusal coverage, maxillary or mandibular, repositioning or stabilising, and made from a variety of different materials.

Choice of materials

The material of choice is laboratory-processed acrylic resin. It is a reasonably hard material which may be easily adjusted and is durable enough to serve as a protective nightguard. Resilient vacuformed vinyl splints are of limited use. Although quick and economic to make they are soon destroyed by determined bruxers. Their resilient surface is not amenable to the production and maintenance of the stable occlusion necessary to achieve muscle relaxation. 13 The use of hard metal alloys such as cobalt/chrome to cover occlusal surfaces is highly inadvisable as it will result in increased wear of the opposing teeth.

Partial coverage splints

Occlusal splints must be worn continually, often for considerable periods of time to be effective. If a splint does not cover all the occlusal surfaces in an arch, unopposed teeth will continue to erupt creating an iatrogenic malocclusion. This applies to both anterior and posterior partial coverage splints and their use cannot therefore be recommended.

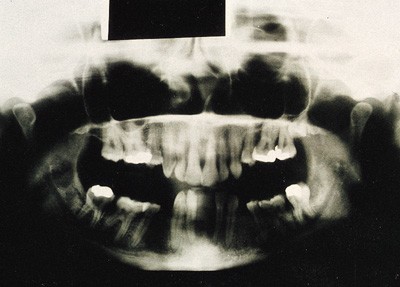

Figure 7 shows a radiograph of a patient who had worn a posterior onlay splint for about 1 year. When she closed into ICP, the posterior teeth were several millimetres apart (the thickness of the splint). The appliance provided no anterior coverage but had permitted the incisors and canines to supra-erupt, and led to intrusion of the posterior segments. An anterior splint would permit the posterior teeth to erupt, so that when the splint was removed the anterior teeth would be apart and anterior guidance would have been lost. In this series a technique will be described where a form of anterior splint (Dahl appliance) is used to gain space to restore worn anterior teeth. This is entirely different as it is a carefully planned procedure in which the anterior space created is filled and guidance restored with restorations placed on the severely worn teeth.

The effect on tooth position of wearing a posterior onlay occlusal splint

Maxillary or mandibular splints?

Providing the requirements of full occlusal coverage, posterior stability, anterior guidance and use of an appropriate material are met, it matters little whether a splint is made on the maxillary or mandibular arch. In Class I and II incisor relationships it is easier to produce an ideal occlusion on a maxillary appliance while the converse is true in Class III situations.

Stabilisation versus repositioning splints

Ramjford and Ash originally described the stabilisation or Michigan-type splint for which detailed fabrication and use will be covered in the final section of the paper. It is a full coverage maxillary splint made from laboratory processed acrylic resin which provides anterior disclusion and stable ICP contacts between a generally flat surface and the opposing teeth. It does not seek to actively reposition the mandible into a predetermined position. It is impossible at the outset to predict the extent and direction of mandibular repositioning, and any attempt to guide the mandible more actively with the splint may actually prevent stabilisation of the retruded position.

Stabilisation splints, through causing muscle relaxation, may also aid the repositioning of a displaced meniscus providing the displacement is neither too severe nor too longstanding.

The use of splints which seek to reposition the mandible in a predetermined position has been advocated, particularly in cases of internal derangement where some studies have shown them to be more effective than stabilisation splints. 14 They possess occlusal surfaces with well-defined fossae into which the opposing teeth locate with the mandible in the desired position. The problem with the use of such splints is that they may not achieve the desired masticatory muscle relaxation: also it is exceptionally difficult if not impossible to predict exactly the position in which the mandible should be located. This position is generally downward and forward from the habitual ICP, the rationale being that the stress on the disrupted joint components will be relieved, permitting them to gradually realign. 15 They also have the considerable disadvantage that following repositioning of the meniscus the patient may be left with a posterior open bite. If this occurs occlusal contacts may gradually re-establish through supra-eruption. Sometimes orthodontic treatment may be necessary to re-establish occlusal stability.

Because of the difficulties in use and the possible irreversible changes which may be caused to the patient's occlusion, the use of these appliances in general practice is recommended only with caution and in experienced hands.

Fabrication, fitting, adjusting and monitoring a Michigan splint

Fabrication.

Maxillary and mandibular full arch alginate impressions are made in metal rimlock trays. The impressions should be quickly poured with the occlusal surfaces downward to ensure accurate reproduction of surface detail. While the stone is setting the poured impressions must be stored in a humid atmosphere. A Tupperware box containing moist paper towels is ideal. When the impressions are removed, the casts should be left to dry for 24 hours; if articulated too soon, the damp stone surfaces will be abraded and rendered inaccurate.

The casts should be mounted in a semi-adjustable articulator using a facebow record to mount the maxillary cast and an interocclusal record taken on the retruded axis to establish the maxillo-mandibular relation. The interocclusal registration is a pre-contact record using a rim of extra hard wax which fits accurately over the maxillary teeth without contacting the soft tissues. A fluid recording medium (Kerrs Tempbond) is applied to the lower surface to register the cusp tips of the mandibular teeth on closure. Control of the mandible is improved by means of a traditional anterior jig which prevents the teeth from coming into contact making manipulation of the mandible easier and determining the vertical dimension of the record.

The incisal pin of the articulator is adjusted to provide a space of a roughly 2 mm between the most posterior teeth, and the outline of the splint drawn on the maxillary cast in pencil. It should extend about 3 mm onto the palatal soft tissues and wrap just over the buccal cusps and incisal edges. The splint will be retained by clipping into proximal, buccal and lingual undercuts and so these should not be blocked out prior to waxing. Two thicknesses of pink baseplate wax are softened and adapted over the cast and then trimmed to the pencil outline. The articulator is closed together until the incisal pin contacts the incisal table, establishing the vertical dimension of occlusion of the splint. The wax is then trimmed and the occlusion adjusted (articulating paper can be used on the wax) to establish the desired occlusion ( fig. 8 ). Contacts are established between the flat surface of the splint and all opposing teeth while a shallow, smooth concave ramp is built up in the anterior region to provide immediate, but smooth, disclusion of the posterior teeth on mandibular movement ( fig. 9 ).

Wax-up of occlusal splint on articulator showing contacts and anterior guidance

Lateral view of splint wax-up showing disclusion of posterior teeth in lateral excursion

Once complete, the maxillary cast is removed from the articulator invested in a flask, the wax boiled out, and then the mould packed with clear acrylic resin which is then processed. The splint is devested, cleaned, trimmed and polished and is then ready for fitting.

Fitting and adjustment

To fit and adjust an occlusal splint will take about 30 minutes. Firstly, the retention is tested and if too tight, acrylic resin is removed with a laboratory carbide bur from the undercut areas around the teeth until the splint seats fully and is adequately retentive. Should the splint exhibit any rocking or lack of seating despite adjustment, it is likely that the casts were inaccurate and new impressions should be made.

Accurate occlusal adjustment requires the use of very thin articulating paper held taut in Millers forceps to ensure that only the actual areas of occlusal contact are marked. The adjustment of the splint is carried out using a large laboratory carbide bur which will adjust the contacts while maintaining a flat occlusal surface. The use of too small a bur will produce indentations in the splint which are undesirable.

Adjustment is carried out with the dental nurse holding two pieces of articulating paper in the patient's mouth and the dentist providing light guidance to the patient's chin with the patient being asked to 'rub forward and back' on the splint. This will guide the mandible toward the retruded position. After marking, the splint is removed and the contacts adjusted until all mandibular teeth make even contact on the splint surface with the mandible in the retruded position. It will probably be impossible at this stage to obtain the correct retruded position because of the state of the patient's neuromuscular system and TMJ's.

Following establishment of these contacts, the splint is adjusted in lateral and protrusive movements. In lateral movements, the guidance is provided by contact between the mandibular canines and the splint surface ( fig. 10 ), which separates all the other teeth. In protrusive movements, disclusion is provided by even contact between the mandibular incisors and the splint ( fig. 10 ). No other teeth should make contact outside ICP.

Adjusted splint — holding contacts (Black), lateral canine guidance (Red), and protrusive (Green)

Once adjustment is complete, the patient is instructed in how to look after the splint and to wear it as much as possible.

Monitoring splint therapy

If an occlusal splint is being used only as a night guard to protect teeth or restorations it is advisable to review the patient after 7 days to check whether their occlusion has remained stable and to readjust if necessary. After this the splint should be checked at each routine examination.

If the splint is being used to treat mandibular dysfunction or for pre-restorative stabilisation the patient must be reviewed and the splint re-adjusted at weekly intervals for as long as is necessary to achieve a stable retruded position. The time necessary for this to occur may vary from a couple of weeks to several months.

At each adjustment the occlusion is re-examined and the splint readjusted to re-establish even contact and to eliminate excursive interferences. A stable relationship has been achieved when the occlusal contacts marked on the splint remain unchanged for two successive appointments.

If splint therapy were initiated to treat mandibular dysfunction no irreversible alteration to the patient's occlusion (equilibration) is generally needed. The patient may be gradually weaned off the splint but told to wear it if their discomfort returns which is often at times of stress.

If the aim of splint therapy was to stabilise the mandible prior to re-organised restorative treatment, stabilisation of the occlusion on the splint must be followed by an accurate mounting of diagnostic casts in the new maxillo-mandibular relationship. Monitoring the progress of splint therapy is usually carried out by observation of the occlusal contacts on the splint at each adjustment appointment. Prior to more complex restorative procedures and for the purposes of research, the effect the splint has on the stability of the retruded position and other mandibular border movements may be followed very precisely using pantographic tracings of mandibular border movements. 3 , 8 , 9

The casts, once re-mounted, can then be used to plan and rehearse the restorative procedures. This may necessitate adjustment but will certainly involve diagnostic waxing.

Conclusions

Patients affected by tooth surface loss need protective management. This is based on the elimination, where possible, of the primary cause with careful selection and use of restorative materials to improve or preserve occlusal stability. Where loads on teeth are high, an occlusal splint can be a very effective way of limiting further wear. If preventive strategies have either not been introduced or not complied with, the dentition may be very worn and fixed restorations impossible to provide. Consequently, removable prostheses are frequently used to restore those severely affected by tooth surface loss, Part 4 of the series discusses the principles of their use.

Schaerer P, Stallard R E, Zander H A, Occlusal interferences and mastication; an electromyographic study. J Prosthet Dent 1967; 17 : 438–449.

Article Google Scholar

Rankow K, Carlsson K, Edlund J, Oberg T . The effect of an occlusal interference on the masticatory system. Odont Revy 1976; 27 : 245–256.

Google Scholar

Howat A P, Capp N J, Barrett N V J . A colour atlas of occlusion and malocclusion . London: Wolfe Publishing Ltd, 1991. Chapters 2,4,10,11.

Furstman L . The effect of loss of occlusion upon the mandibular joint. Am J Orthod 1965; 51 : 1245.

Ramjford S P, Walden J M, Enlow R D . Unilateral function and the temporomandibular joint in Rhesus Monkeys. Oral surg 1971; 32 : 237.

Solberg W K, Clark G T, Rugh J D . Nocturnal electromyographic evaluation of bruxism patients undergoing short-term splint therapy. J Oral Rehab 1975; 12 : 215–223.

Beard C C, Clayton J A . Effects of occlusal splint therapy on TMJ dysfunctions. J Prosthet Dent 1980; 44 : 324.

Shields J M, Clayton J A, Sindledecker L D . Using pantographic tracings to detect TM J and muscle dysfunctions. J Prosthet Dent 1978; 39 : 80.

Crispin B J, Myers G E, Clayton J A . Effects of occlusal therapy on pantographic reproducibility of mandibular border movements. J Prosthet Dent 1978; 40 : 29–34.

Feinmann C, Harris M . Psychogenic facial pain — Parts I & II. Br Dent J 1984; 156 : 165,205.

Forsell H, Kirveskari P, Kangasniemi P . Changes in headache after treatment of mandibular dysfunction Cephalagia. 1985 5 : 229–36.

Forsell H, Kirveskari P, Kangasniemi P . Response to occlusal treatment in headache patients previously treated by mock occlusal adjustment. Acta Odont Scand 1987; 45 : 77–80.

Nevarro E, Barghi N, Rej R . Clinical evaluation of maxillary hard and resilient occlusal splints. J Dent Res Abstract 1246. Special Issue March 1985.

Anderson G, Schulte J, Goodkind R . Comparative study of two treatment methods for internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. J Prosthet Dent 1985; 53 : 392–397.

Solberg W. K . Temporomandibular disorders . London: BDJ Handbook, 1986, p96.

Capp N J . Temporomandibular joint dysfunction — its relevance to restorative dentistry. Part 2: splint therapy and restorative considerations. Rest Dent 1986: 2 ; 62–68.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author is most grateful to Mosby-Year Book Europe Ltd for permission to use the illustrations in Figures 1 , 2 , 8 and 9 . This article is based on a presentation at The Medical Society of London on 2 November 1994 as part of the Alpha Omega lecture programme.

The Series Editors are Richard Ibbetson and Andrew Eder of the Eastman Dental Institute for Oral Healthcare Sciences and the Eastman Dental Hospital

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Eastman Dental Institute for Oral Healthcare Sciences, University of London, 256 Gray's Inn Road, London, WC1X 8LD

Specialist in Restorative Dentistry, 35 Harley Street, London, W1N 1HA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Capp, N. Occlusion and splint therapy. Br Dent J 186 , 217–222 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800069

Download citation

Published : 13 March 1999

Issue Date : 13 March 1999

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4800069

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The management of tooth wear with crowns and indirect restorations.

- A. Preiskel

- D. Bartlett

British Dental Journal (2018)

Unintended changes to the occlusion following the provision of night guards

- T. Bereznicki

- N. H. F. Wilson

The occlusal splint therapy

- J.-D. Orthlieb

international journal of stomatology & occlusion medicine (2009)

Patient responses to vacuum formed splints compared to heat cured acrylic splints: pilot study

- Aysen Nekora

- Gulümser Evlioglu

- Halim Issever

Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery (2009)

Fitting acrylic occlusal splints and an experimental laminated appliance used in migraine prevention therapy

British Dental Journal (2006)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Movements and Mechanics of Mandible Occlusion Concepts and Laws of Articulation

- First Online: 29 December 2018

Cite this chapter

- Yasemin K. Ozkan 2

2499 Accesses

1 Citations

Mandibular movement occurs as a complex series of interrelated three-dimensional rotational and translational activities. Jaw movements or mandibular kinematics has important applications in many fields of clinical dentistry and provides a basis for modern concepts of dental occlusion. In all branches of dentistry, occlusion is defined as the most important as well as the most confusing concept. Any contact between the occlusal surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular teeth is defined as occlusion. To understand the concept of occlusion, it is necessary to have knowledge about a broad range of subjects, including the contact relation between teeth; mechanics, mathematics, and geometry of jaw movements; the biological response of natural teeth under different conditions; and functional analysis. In this chapter, the related definitions, mandibular border movements, types of occlusion, occlusion in complete dentures, rules and laws of articulation, and incisal and condylar path inclinations are elucidated.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Further Reading

Bosman F, Erkelens CJ. Computer simulation of mandibular movements. J Biomech. 1985;18:528–9.

Article Google Scholar

Chen DC, Lai YL, Chi LY, Lee SY. Contributing factors of mandibular deformation during mouth opening. J Dent. 2000;28:583–8.

Clough HE, Knodle JM, Leeper SH, Pudwill ML, Taylor DT. A comparison of lingualized occlusion and monoplane occlusion in complete dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;50:176–9.

Gordon SR, Stoffer WM, Connor SA. Location of the terminal hinge axis and its effect on the second molar cusp positioning. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;52:99–105.

Keshvad A, Winstanley RB. Comparison of the replicability or routinely used centric relation registration techniques. J Prosthodont. 2003;12:90–101.

Kinderknecht KE, Wong GK, Billy EJ, Li SH. The effect of a deprogrammer on the position of the terminal transverse horizontal axis of the mandible. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;68:123–31.

Koolstra JH, van Eijden TMGJ. The jaw open-close movements predicted by biomechanical modelling. J Biomech. 1997;30:943–50.

BR L. Complete denture occlusion. Dent Clin N Am. 2004;3:641–65.

Google Scholar

Nimmo A, Kratochvil FJ. Balancing ramps in nonanatomic complete denture occlusion. J Prosthet Dent. 1985;53(3):431–3.

Parr GR, Loft GH. The occlusal spectrum and complete dentures. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1982;3:241–50.

PubMed Google Scholar

Peck CC, Langenbach GEJ, Hannam AG. Dynamic simulation of muscle and articular properties during human wide jaw opening. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:963–82.

Rangarajan V, Gajapathi B, Yogesh PB, Ibrahim MM, Kumar RG, Karthik M. Concepts of occlusion in prosthodontics: a literature review, part I. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2015;15:200–5.

Rangarajan V, Yogesh PB, Gajapathi B, Ibrahim MM, Kumar RG, Karthik M. Concepts of occlusion in prosthodontics: a literature review, Part II. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2016;16:8–14.

Taylor TD, Wiens J, Carr A. Evidence-based considerations for removable and dental implant occlusion: a literature review. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;94:555–60.

Zarb GA, Bolender CL, Hickey JC, Carlsson GE. Boucher’s prosthodontics treatment for edentulous patients. 10th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1990. p. 330–51.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Prosthodontics, Marmara University, Istanbul, Turkey

Yasemin K. Ozkan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yasemin K. Ozkan .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Prosthodontics, Marmara University Faculty of Dentistry, Istanbul, Turkey

Yasemin K. Özkan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Ozkan, Y.K. (2018). Movements and Mechanics of Mandible Occlusion Concepts and Laws of Articulation. In: Özkan, Y. (eds) Complete Denture Prosthodontics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69032-2_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69032-2_8

Published : 29 December 2018

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-69031-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-69032-2

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Pocket Dentistry

Fastest clinical dentistry insight engine.

- Dental Hygiene

- Dental Materials

- Dental Nursing and Assisting

- Dental Technology

- Endodontics

- Esthetic Dentristry

- General Dentistry

- Implantology

- Operative Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

- Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Orthodontics

- Pedodontics

- Periodontics

- Prosthodontics

- Gold Member

- Terms and Condition

Occlusion, the Periodontium and Soft Tissues

The term “fremitus” describes tooth mobility when occlusal contacts are performed. It may either be observed visually or felt through the examiner’s fingertips, or both. It may occur when the patient closes into the intercuspal or retruded positions, or during excursions of the mandible.

Occlusal factors may be important in the aetiology of increased mobility, but there are often other reasons. These are considered in the following section. Where the occlusion interacts with these factors, it may worsen or prevent resolution of the mobility. An increased mobility associated primarily to occlusal overload is relatively uncommon, but it can mystify the unwary dentist, particularly when it affects multiple teeth.

Non-occlusally Related Causes for Tooth Hypermobility

The commonest cause of increased tooth mobility is inflammatory periodontal disease. All clinicians are aware that teeth tighten after successful periodontal treatment, but increased mobility can persist after the inflammation has been eliminated. Characteristically, radiographs of affected teeth show reduced alveolar support, but a normal periodontal ligament space. This is simply an amplification of physiological mobility (Fig 5-1) because of long clinical crown height and short attachment. Despite the apparent increased mobility, such teeth do not require occlusal treatment if not subject to occlusal interference.

Fig 5-1 Although the tooth on the right is more mobile than the tooth on the left, the periodontal ligament is healthy and not widened. The increased mobility at the level of the occlusal plane is simply related to the longer clinical crown.

Only if the patient has discomfort from excessively hypermobile teeth during function, or if the mobility is increasing, might splinting be beneficial.

Other non-occlusal causes of increased mobility include:

root resorption

loss of periradicular bone support, for example due to periradicular inflammation or after apical surgery

recent trauma causing subluxation

fractured root

hormonal, occurring occasionally during pregnancy.

Occlusally Related Causes for Tooth Hypermobility

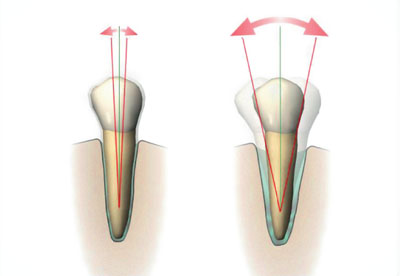

Habits such as bruxism can subject the teeth to loads which are higher and longer lasting than during normal function. This may, for poorly understood reasons, result in the periodontium adapting to the increased loads, rather than the neuromuscular system limiting load generation, as might be expected. Teeth with normal bone levels and normal attachment can still become hypermobile under such circumstances, with the response regarded as a physiological reaction to the mechanical insult. This is sometimes called “primary occlusal trauma”. Characteristically, the periodontal ligament becomes widened (Figs 5-2 and 5-3).

Fig 5-2 The tooth on the right shows the physiological response to a higher than normal occlusal force; its periodontal ligament has become widened (primary occlusal trauma).

Fig 5-3 A premolar with a widened periodontal ligament space. This is periodontal ligament widening, caused in this case by abnormal loading from a denture clasp.

Of course, teeth with a reduced but healthy periodontal support may undergo an increase in existing hypermobility if subjected to direct or indirect occlusal trauma. This is sometimes called “secondary occlusal trauma”. This terminology is not useful because the response to both primary and secondary occlusal trauma simply represents a normal physiological adaptation of the periodontium to increased occlusal loading.

A thorough clinical and radiographic examination will enable the cause of hypermobility to be identified. Increasing mobility is an important clinical symptom and sign to look out for. It can indicate an occlusal discrepancy which will benefit from correction.

In addition to conventional periodontal therapy, management of hypermobility caused by occlusal factors should be directed at:

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Related posts:

- Occlusion and Fixed Osseointegrated Implant Restorations

- The Intercuspal Position and Dentistry

- Normal Function and Avoiding Damage to Restored Teeth

- Deflective Contacts, Interferences and Parafunction

- Occlusion and Temporomandibular Disorders

- Occlusal Techniques

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

Comments are closed for this page.

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

What is pet dental insurance?

Coverage details, choosing the right dental insurance, benefits of pet dental insurance, how to get pet dental insurance, pet dental insurance: protecting your pet's oral health.

Affiliate links for the products on this page are from partners that compensate us (see our advertiser disclosure with our list of partners for more details). However, our opinions are our own. See how we rate insurance products to write unbiased product reviews.

- Pet insurance with pet dental coverage can be affordable while protecting your pet's health.

- The best pet insurance plans include coverage for periodontal disease.

- Scheduling regular pet dental cleanings can help you avoid lapses in coverage.

Just as brushing and flossing are essential for people, regular dental care is vital for pets, especially cats and dogs. The American Veterinary Medical Association recommends that pets get proper dental care annually (which can be part of their yearly physical).

"Dental health is an integral part of a pet's overall health and should be a key part of their preventive care routine," says Dr. Ari Zabell , a veterinarian with Banfield Pet Hospital.

Dental treatments for periodontal disease, broken teeth, or tumors can be costly. So, more pet owners are looking into pet dental insurance. If you shop carefully, pet dental insurance and other pet insurance protections for all your pet's needs can be open to you.

Some of the best pet insurers , like Embrace Pet Insurance offer comprehensive coverage to care for your pet's pearly whites. Read on to learn more about picking a plan and using it when the time comes.

In most cases, pet dental insurance can't be bought as a standalone policy, according to Dr. Brian Evans, clinical director at the online veterinary clinic, Dutch.

Zabell expands on this point, saying, "Dental insurance for pets is almost always part of a larger pet insurance plan." Pet dental is a natural part of the conversation after you answer the question of whether pet insurance is worth it with a yes.

Definition and scope of coverage

Pet insurance provides reimbursement for unforeseen or emergency care. Since dental pet insurance is typically a feature of your pet insurance policy, you'll receive coverage for dental care related to accidents and illnesses. The following are examples of dental conditions and treatments covered under a pet insurance policy:

- Periodontal disease

- Tooth abscesses

- Cancerous oral growths and tumors

- Fractured tooth

Your pet insurance coverage is based on a reimbursement model. You pay for services upfront then submit your claim to your insurance company for reimbursement. It might seem like a hassle as we're used to human medical providers taking care of the claims process for us. However, there is a silver lining. You won't need to worry about in-network vs. out-of-network providers for your pet's healthcare.

"Vets do not have a concern about which insurance plan you have as they are not a part of that process," Evans says.

Difference between dental insurance and wellness add-ons

Dental insurance comes with your standard accident and illness policy. Dental insurance is also available through a wellness plan at an additional fee.

Pet wellness plans cover the cost of preventative dental care, such as routine cleanings or checkups. In contrast, pet insurance policies cover medically necessary treatments and procedures like tooth extractions or root canals.

Depending on your insurance policy, pet dental insurance will cover emergency procedures and routine care. However, it excludes coverage for pre-existing conditions and certain types of pets.

Routine dental cleanings

Routine dental cleaning prevents severe dental illnesses in the long run. Wellness plans are typically purchased as add-ons to your regular insurance policy. These plans have their own premiums and coverage limits. Unlike your base policy, they generally don't require deductibles or co-pays.

Emergency dental procedures

Emergency dental procedures are covered under your base pet insurance policy. Some of these procedures and treatments include:

- Tooth extractions

- Root canals

- Prescription medicine

Exclusions and limitations

Most pet insurance plans won't cover pre-existing conditions. Since an astounding 80% of dogs have dental disease by the time they're three years old, getting coverage early is critical.

"The best way to ensure your pet's periodontal disease will not be considered pre-existing is to purchase the pet insurance while they still have their puppy teeth," Evans says.

Another exclusion to be aware of is your pet's breed and age. Insurance companies may deny coverage to certain breeds and older pets because they are more prone to health conditions. If your insurer doesn't restrict a high-risk pet, your insurance premiums will likely increase.

The right dental insurance policy offers coverage that aligns with your pet's needs at a price point comfortable for you. Comparing insurance providers can help you sift through the market and find a policy that meets your criteria.

Factors to consider

When choosing a pet insurance policy, you'll want to consider the following factors:

- Coverages: Know your pet's health needs and find a policy that covers them. The best pet dental insurance plans should cover periodontal disease, inflammation of the gums, and tissue around the teeth. This is the most common dental condition in cats and dogs.

- Premiums: The average cost of an accident-only pet insurance policy is $10.18 per month for cats and $16.70 for dogs. The average cost for a comprehensive policy is $32.25 per month for cats and $53.34 for dogs. But it varies widely based on your pet's type, breed, age, and where you live

- Deductible: The amount you need to pay toward your pet's care before the insurance kicks in. Usually, this is deducted from the first reimbursement.

- Reimbursement level: This is the percentage of the vet's invoice your insurer will cover. Usually, reimbursement levels range between 70% and 90% of the procedure costs.

- Coverage maximum: This max is the highest dollar amount your pet insurance will pay for a claim.

For the most comprehensive pet medical coverage, look for a pet insurance plan with unlimited coverage and a reimbursement rate of 80 to 90% (you pay 10-20% of your vet bills after the deductible).

"Some pet insurance companies will also say they cover dental cleanings but limit the reimbursement to a small portion of the actual cost," says Evans. "The entire dental cleaning procedure may cost $700, but the pet insurance will only reimburse you $150."

Comparing insurance providers

Shopping around for pet insurance helps you get the lowest price on the coverages you need. To compare insurance policies, get quotes for your pet from a few different insurance companies. Make sure each quote has a similar deductible, coinsurance, and policy limit for the most accurate apples-to-apples comparison.

Dental care insurance for your pet ensures that your pet's teeth are taken care of without the financial burden. Here are a few of its benefits:

Preventing costly dental problems

Preventative care is the best way to avoid complicated and costly dental problems as your pet ages. But routine cleaning isn't cheap. According to Spot, an examination, removal of plaque and tartar, and polishing cost between $150 to $350. Meanwhile, the monthly premium of a basic wellness policy can be as little as $9.95 for hundreds of dollars in coverage.

Enhancing overall pet health

Many pet owners avoid the vet or avoid certain treatments because they can get expensive. Whether you have a sizable emergency fund or wiggle room in your budget, every pet deserves quality healthcare. Pet insurance is a financial tool you can leverage to ensure your furry friend lives a long and healthy life.

Peace of mind for pet owners

Dental procedures come at a hefty price tag. According to Spot, a pet insurance company, a single tooth extraction will run you about $50 to $200. Extractions for multiple teeth can cost $1,000 or more. More complex procedures like a root canal or surgery for a fractured jaw can amount to thousands of dollars. Pet dental insurance allows you to pay only a fraction of that price.

You get pet dental insurance the same way you'd get a pet insurance policy or a wellness add-on.

- Step 1: Apply for a policy — After finding a policy that meets your pet's coverage needs and budget, fill out an application with the pet insurance company. The insurer will request personal information such as your location and contact information and your pet's details, such as their name, gender, and breed. This information will be used to assess your premiums.

- Step 2: Customize your coverages — Most insurance companies let you choose between an accident-only policy and an accident and illness policy. You may also have the option to add a wellness plan. Adjust factors such as deductibles, reimbursement rates, and coverage limits to your specific needs and financial situation.

- Step 3: Read the fine print — Review your policy's terms and conditions to understand any exclusions, limitations, waiting periods, or other important details that may apply.

- Step 4: Purchase your policy — At checkout, you'll have the option to pay an annual or monthly premium. Once you've made your decision, proceed by entering your payment details and confirming your payment to secure your coverage.

- Step 5: Provide requested documentation— Your insurer may ask for additional documentation, such as your pet's medical record or a physical exam to check for any pre-existing conditions.

How to file a pet dental insurance claim