my S hakespeare

Sign in with:

Or use e-mail:.

- Using myShakespeare

- Direct Links to Videos

- Animated Summary

- Quick Study

- Shakespeare's Life

- Elizabethan Theater

- Religion in Hamlet

- Song Summary

- Hamlet's Madness

- Video Credits

You are here

A discussion of the phrase "undiscovered country" in Act 3, Scene 1 of myShakespeare's Hamlet.

myShakespeare | Hamlet 3.1 "The Undiscovered Country"

SARAH: Hamlet sums up here: if we put up with a tiresome life and all its burdens, it must be because we're afraid of the unknown that faces us after death.

RALPH: What an expression he uses here for the afterlife! "The undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveller returns." What's so great about this is how Shakespeare mixes the personal and the subjective with the general and the objective. Death is an undiscovered country for me, personally, because I'm still alive.

SARAH: And yet, others have died before and discovered it. But they're like travellers who never come back — we can't learn from their experience, no matter how universal it is.

RALPH: Death is something we all go through, and yet we know absolutely nothing about it.

- For Teachers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

William Shakespeare: 'The undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns.'

The undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns.

"The undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveler returns." These enigmatic words penned by William Shakespeare in Hamlet have garnered much attention and interpretation over the centuries. At first glance, the quote simply refers to death and the unknown realm that lies beyond. It speaks to the finality of death, signifying that once we venture into that undiscovered country, no one returns to share their experience. This notion has a profound impact, forcing us to contemplate our mortality and the mysteries that lie beyond life.However, beyond this conventional interpretation lies a broader philosophical concept that can add a layer of intrigue to the quote. Let us consider the idea that Shakespeare might have been alluding not only to physical death but also to the intangible realms of the human mind and consciousness. Just as death takes us to an uncharted territory, the inner workings of our mind can be considered as an undiscovered country as well.In this context, the quote suggests that once we delve deep into our own consciousness, we encounter aspects of our being that remain unexplored. The mind, with its depths and complexities, can be seen as a vast terrain waiting to be discovered. As travelers within ourselves, we embark on a journey of self-exploration, seeking to understand the intricacies of our thoughts, emotions, and desires.Ironically, the mind, like the physical world we inhabit, also holds its own boundaries - bourns that limit our exploration. These limits can manifest as cognitive biases, societal norms, and deeply ingrained beliefs that confine our understanding. Similar to the undiscovered country beyond death, the boundaries of our own consciousness often prevent us from fully comprehending our own potential and the true nature of reality.Moreover, this philosophical interpretation offers an interesting juxtaposition to the traditional understanding of Shakespeare's quote. While physical death signifies an end and a departure from the living world, the exploration of our own consciousness opens up the possibility of transformation and self-realization. Unlike death, which remains the undiscovered country from which no traveler returns, the unexplored reaches of our mind present an opportunity for growth, evolution, and self-discovery.By considering this expanded perspective, we can reflect on the significance of Shakespeare's quote in a more thought-provoking manner. It encourages us to explore not only the external world but also the internal landscapes of our own consciousness. Just as the physical world has its boundaries that we may never fully transcend, our minds too have inherent limitations that we must acknowledge and strive to challenge.In conclusion, William Shakespeare's quote posits both a literal and metaphorical interpretation. On the surface, it highlights the finality of death and the mystery that lies beyond. However, a closer examination reveals a philosophical concept that links this notion to the internal exploration of our own consciousness. By embracing this expanded interpretation, we are prompted to seek a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us. Just as no traveler returns from the undiscovered country beyond death, we must embark on the lifelong pilgrimage within our own minds, venturing into the uncharted territories of our consciousness, in a constant pursuit of self-discovery and personal growth.

William Shakespeare: 'When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions.'

William shakespeare: 'love looks not with the eyes, but with the mind, and therefore is winged cupid painted blind.'.

To Be or Not to Be: Expert Analysis of Hamlet’s Soliloquy for Teens

June 7, 2023

From Calvin and Hobbes to Star Trek to The Simpsons, Hamlet’s soliloquy “To Be or Not To Be” is one of the most commonly cited lines of Shakespeare. But beyond the evocative first line, what is the underlying meaning and analysis? We will dive into an analysis of Hamlet’s soliloquy shortly but first some brief context.

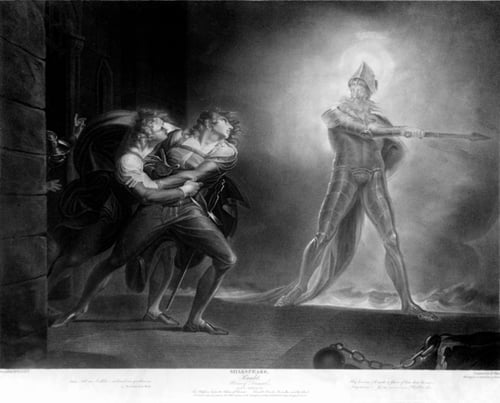

Hamlet Summary – Putting “To Be or Not to Be” in context

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark , more often referred to simply as Hamlet, is one of the English playwright William Shakespeare’s most well-known plays. It was written likely between 1599 and 1601. The play centers on Prince Hamlet, who is distraught with grief around his father’s murder. At the start of the play, Hamlet is confronted by his father’s ghost who informs him that the king was murdered by the king’s own brother (Hamlet’s uncle), Claudius, who has inherited the throne and married his widow (and Hamlet’s mother), Gertrude.

While at first singularly committed to avenging his father’s death, Hamlet’s contemplative nature causes him to oscillate between the desire to act immediately and melancholic reluctance, rageful vengeance, and existential despair. This context helps us understand the tense conundrums expounded upon in this soliloquy. However, as one can see from its widespread citation, one can also perform an analysis of Hamlet’s soliloquy “To Be or Not To Be” on its own.

What is a Soliloquy?

A soliloquy is a specific kind of monologue. It entails a single character speaking for a period of time while alone. In other words, the character is talking aloud to themselves. (For more examples and explanations of “soliloquy”, check out this link !). Now let’s walk through the text itself.

Hamlet’s Soliloquy – Meaning & Analysis

He begins with that well-known line:

“To be, or not to be: that is the question.” Already the stakes are high. Hamlet is essentially asking whether to choose life or death, being or not being, endurance or suicide. He goes on to say “Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer / The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune , /Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, / And by opposing end them?”

This elaborates and complicates on the binary of life or death set up in the first line. He wonders if would be more honorable to endure the suffering he faces due to his terrible and painful “fortune” or to end both his life and troubles in one fell swoop. Take note as well of the military figurative language peppered throughout his personal monologue, such as in words like “noble,” “take arms,” and “the slings and arrows.” As a prince embroiled in royal drama, his intimate woes are entangled with the national politics. Often, this means bloody war. Furthermore, the metaphors signal that there is a war within his own mind due to his agonizing situation. While desiring relief from life’s suffering, he is not totally resolved to die.

He turns to contemplate death, saying:

“To die: to sleep; / No more; and by a sleep to say we end / The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks / That flesh is heir to, ’tis a consummation / Devoutly to be wish’d.”

He equates death to sleep, where suicide is framed not as violent but as a restful space that ends the “heart-ache” and pain he endures in wakeful life. The isolation of “No more” is emphatic and multifaceted. It signals both no more life and no more suffering. He also emphasizes the many forms of pain he desires respite from. There is the “thousand natural shocks” that, through the word natural, evoke an inevitable yet immense pain and then there is the “heart-ache” that appears more intentional and singular in the specific murder of his father. His father’s death and his princely position is further invoked through the word “heir,” given that he is the heir to his father’s crown. Death is a desired (“devoutly…wish’d”) ending (“consummation”) to these manifold sufferings.

“To Be or Not to Be” Soliloquy- Meaning & Analysis (Continued)

The poetics surface through the use of anaphora—repetition of a word or phrase at the start of a line. Hamlet repeats the lines “to die, to sleep,” emphasizing the equation between death and sleep, while also using repetition in a lullaby-like fashion through the songlike refrain. He proceeds to say:

“For in that sleep of death what dreams may come / When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, / Must give us pause: there’s the respect / That makes calamity of so long life.”

For the agonizing Prince, life (“this mortal coil”) is equated to “calamity” while death is equated to dreaming. But this portion is not merely repetition of his previous aspiration for relief through death. He is beginning to hypothesize why people continue to live in spite of such agonies. In this section, he conjectures that people might continue to suffer “so long” because they don’t know “what dreams may come” on the other side of life. In other words, people might rather suffer than risk the unknown.

He continues to contemplate why people endure suffering:

”For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, / The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, / The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay, / The insolence of office and the spurns / That patient merit of the unworthy takes, / When he himself might his quietus make / With a bare bodkin?”

He wonders how people can “bear” myriad injustices, ranging from the more general “whips and scorns of time” to oppressive acts to difficulty in love to the inaction of the law, and so on. Note again how the most personal matters (“the pangs of despised love”) enmesh with broader structural failings (such as “the law’s delay”). Hamlet sees pain and injustice at every scale—the personal, the political, the individual, and the societal. Hamlet views himself as the victim of legal and personal corruption. Of course, the two are heightened and enmeshed; his father’s murder by his uncle lives at the intersection of both.

It is an open-ended question for the reader/audience as to whether Hamlet is accurately assessing his life’s misfortunes or if he is exaggeratedly framing himself as a victim. Is Hamlet totally at the mercy of unjust forces or does he have agency to change his fortune? Can Hamlet access agency from within grief and despair?

Following this litany of life’s woes, Hamlet shifts from the desire to escape suffering to the fear of the unknown. He asks:

“who would fardels bear, / To grunt and sweat under a weary life, / But that the dread of something after death, / The undiscover’d country from whose bourn / No traveller returns, puzzles the will / And makes us rather bear those ills we have / Than fly to others that we know not of?” He essentially argues the no one would grunt through such burdens (“fardels”) if it were not for a fear of what happens after one dies. Death, while an unknown, is a final place from which “no traveller returns.”

The choice to live is framed as something that “puzzles the will,” derived from the pressures of “dread” at the uncertainty of what comes after. In some ways, he is arguing the choice to live arises from adherence to the age old maxim “better the devil you know than the devil you don’t.” This confounds typical narratives and philosophies around the will to live. Endurance of suffering is not framed as a valiant force of the will prevailing against larger forces. It is instead framed as submission to fear of the unknown. Even the word “fly” implies a sort of agency and freedom in death. The choice is not quite between life and death but between the known and the unknown.

Hamlet’s speech forces the listener to contend with existential questions by reversing typical narratives that yoke life to agency and death to passivity. Instead, he prods at the theory that to live is to be passive in the face of human fear of randomness and chance at the unknown of death. This does not mean that he is bluntly choosing death over life, but interrogating the terms of life and death from within a space of grief and betrayal. His grief and betrayal dismantles his trust in the justice of personal, political, and legal systems. This forces readers to ask whether he is expanding his personal misfortunes to a falsely universal level or if these experiences have opened his eyes to extant and entrenched corruption abound.

Following this string of rhetorical questions, he says: “Thus conscience does make cowards of us all; / And thus the native hue of resolution / Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, / And enterprises of great pith and moment / With this regard their currents turn awry, / And lose the name of action.” One could interpret the adage-like phrase “conscience does make cowards of us all” to mean that conscience’s fear of death turns all into cowards. However, another interpretation based on the previous rhetorical questions could expand to mean that it is rather the fear of the unknown that reduces everyone to cowards. By virtue of saying “all,” Hamlet includes himself in this category, thus revealing that he has chosen life. Nevertheless, he frames the choice of life as the cowardly choice.

The lack of virtue in his choice is underscored through the phrase “the native hue of resolution / is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought.” He depicts his resolution or thought process as sickly and pale. His thoughts render him weak. He loses “the name of action” and becomes swept up, indecisive, and ineffectual. Indeed, the form of the soliloquy mirrors its content. The soliloquy “To Be Or Not To Be” seems to frame the question increasingly inwards around Hamlet’s own desire to live or to die. He is solo and he is in many ways thinking mostly about his own decision to take his life or continue forth.

Yet the theme of life or death also extends toward his potential actions. Were he to kill Claudius, his uncle who he believes slaughtered his father, and Hamlet believes that life is cowardly suffering, then is it a gift to give death to his uncle? Even though it is fraught, Hamlet ultimately decides to continue to live and continue his plot to seek vengeance upon his uncle.

He then notices his conflictual love interest, “The fair Ophelia” approaching. This ends the soliloquy on the level of plot, because he is interrupted, and on the level of form, because he is no longer alone.

The speech forces us to question the idea of agency in life, within Hamlet’s perspective and beyond. Is it more cowardly to live or to die? Do we access agency more by living amidst suffering or by choosing death? This theme intersects with and diverges from what later would come to be termed Existentialism, a branch of philosophy associated most closely with 19th and 20th-century European thinkers. Existentialism typically contends with whether life itself has inherent meaning or is essentially random. Hamlet questions life’s value and significance, and ultimately assigns life neither meaning nor lack thereof but rather a position of passivity, struggle, and powerlessness. Hamlet views life as a known entity of struggle while it is death that contains randomness and chance.

Furthermore, by highlighting the way Hamlet uses metaphors of war to describe his internal turmoil and comingled grievances of the state and of the intimate, we can see how the speech is making an argument potentially about politics and individual power. If the state is corrupt, do individuals have the power to change that corruption? Or do individuals lack the power to do anything but suffer under endlessly corrupt systems? Would it be more willful to endure or to exit the system entirely? Hamlet’s role as a Prince collapses the personal and the political. He simply cannot separate his personal relationships (father-son, lovers, uncle-nephew, et cetera) from their political valences (king, prince, queen, et cetera).

Hamlet’s own ability to reason is thrown into question. In addition to his pretend madness, this speech thematizes how his utter grief and despair affect his ability to reason. The repetition of sleeping and dreaming connotes a relation between death and peacefulness, while also evoking the underlying surreality that penetrates waking life. Is Hamlet’s view of reality clear and rational? Or is his reality clouded by how the nightmarish circumstances have affected his ability to be reasonable? In this way, a central theme of the play/soliloquy is the struggle to determine what is truly real. What is reality, what is belief, what is madness, what is dream?

Hamlet’s soliloquy also makes us ask how we decipher fact from fiction, reality from performance. The play and this soliloquy in particular make use of the theatrical fictive frame. Hamlet has decided to act as if he has gone mad as part of his plan to exact revenge and extract information. Yet clearly his suicidal ideation makes us wonder if his grasp on reality has been actually shaken.

The central part of his plan involves staging a play that contains a similar murder plot as the one he believes Claudius commited against his father. Hamlet intends to observe Claudius’ reaction to determine his guilt. These elements of a ‘ play within a play ’ structure and the fictive character of Hamlet deciding to intentionally put in a ‘fake’ act within the already existing performance of an actor make us question what is reality and what is a performance. Is Hamlet’s character actually mad or is he acting mad?

To Be or Not to Be – Parting Thoughts

We, as readers, are put in the hot seat. In our analysis of Hamlet’s soliloquy “To Be Or Not To Be” we are reading the words for an actor pretending to play Hamlet pretending to go mad. Where do you, as a reader, stand? A rich exercise to go even deeper is to listen to several performances of the soliloquy after analyzing the text. This will allow you to see how different actors interpret “To Be Or Not To Be” through their performance!

Additional Resources

If you enjoyed this article, you may benefit from checking out other blogs in our High School Success section including:

- 30 Literary Devices High School Students Should Know

- 20 Rhetorical Devices High School Students Should Know

- Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken – Analysis and Meaning

- Great Gatsby Themes & Analysis

- High School Success

An experienced instructor, editor, and writer, Rebecca earned a BA in English from Columbia University and is presently pursuing a PhD at the CUNY Graduate Center in English. Her writing has been featured on The Millions , poets.org , The Poetry Project Newsletter , Nightboat Books blog, and more, and she received the Academy of American Poets Poetry Prize and Arthur E. Ford Prize for her poetry collections.

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- College Success

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

I am a... Student Student Parent Counselor Educator Other First Name Last Name Email Address Zip Code Area of Interest Business Computer Science Engineering Fine/Performing Arts Humanities Mathematics STEM Pre-Med Psychology Social Studies/Sciences Submit

Hamlet Shakescleare Translation

Hamlet Translation Act 3, Scene 1

CLAUDIUS, GERTRUDE, POLONIUS, OPHELIA, ROSENCRANTZ, and GUILDENSTERN enter.

And can you by no drift of conference Get from him why he puts on this confusion, Grating so harshly all his days of quiet With turbulent and dangerous lunacy?

And the two of you haven’t been able to figure out by talking with Hamlet why he’s acting so oddly, acting with a wild and dangerous lunacy that’s such a huge shift from his earlier calm behavior?

ROSENCRANTZ

He does confess he feels himself distracted. But from what cause he will by no means speak.

He admits he feels somewhat crazy, but won’t talk about the cause.

GUILDENSTERN

Nor do we find him forward to be sounded. But with a crafty madness keeps aloof When we would bring him on to some confession Of his true state.

And he’s not willing to be questioned. His insanity is sly and smart, and he slips away from our questions when we try to get him to tell us about how he’s feeling.

Everything you need for every book you read.

Did he receive you well?

Did he treat you well?

Most like a gentleman.

Yes, he treated us like a gentleman.

But with much forcing of his disposition.

But also as if he he had to force himself to act that way.

Niggard of question, but of our demands Most free in his reply.

He didn’t ask many questions, but answered our questions extensively.

Did you assay him? To any pastime?

Did you try to get him to do something fun?

Madam, it so fell out, that certain players We o’erraught on the way. Of these we told him, And there did seem in him a kind of joy To hear of it. They are about the court, And, as I think, they have already order This night to play before him.

Madam, as it happened, we crossed paths with some actors on the way here. When we mentioned them to Hamlet, he seemed to feel a kind of joy. They are at the court now, and I think they’ve been told to perform for him tonight.

‘Tis most true, And he beseeched me to entreat your Majesties To hear and see the matter.

That’s true, and he asked me to beg both of you, your Majesties, to come and watch.

With all my heart, and it doth much content me To hear him so inclined. Good gentlemen, give him a further edge, And drive his purpose on to these delights.

With all my heart, I’m glad to hear of his interest. Gentlemen, try to nurture this interest of his, and keep him focused on these amusements.

We shall, my lord.

We will, my lord.

ROSENCRANTZ and GUILDENSTERN exit.

Sweet Gertrude, leave us too, For we have closely sent for Hamlet hither, That he, as ’twere by accident, may here Affront Ophelia. Her father and myself (lawful espials) Will so bestow ourselves that, seeing unseen, We may of their encounter frankly judge, And gather by him, as he is behaved, If ’t be the affliction of his love or no That thus he suffers for.

Dear Gertrude, please go as well. We’ve sent for Hamlet as a way for him to meet with Ophelia, seemingly by chance. Her father and I—spying for justifiable reasons—will place ourselves so that we can’t be seen, but can observe the encounter and judge from Hamlet’s behavior whether love is the cause of his madness.

I shall obey you . And for your part, Ophelia, I do wish That your good beauties be the happy cause Of Hamlet’s wildness. So shall I hope your virtues Will bring him to his wonted way again, To both your honors.

I’ll do as you ask.

[To OPHELIA] As for you, Ophelia, I hope that your beauty is the reason for Hamlet’s insane behavior. I hope also that your virtues will get him to return to normality, for both of your benefits.

Madam, I wish it may.

I hope it too, madam.

GERTRUDE exits.

Ophelia, walk you here. [to CLAUDIUS] Gracious, so please you, We will bestow ourselves. [to OPHELIA] Read on this book That show of such an exercise may color Your loneliness. —We are oft to blame in this, ‘Tis too much proved, that with devotion’s visage And pious action we do sugar o’er The devil himself.

Ophelia, walk over here.

[To CLAUDIUS] Your Majesty, if you agree, let’s go hide.

[To OPHELIA] Read this prayer book, to make you’re being alone seem natural. You know, this is actually something people can be blamed for doing all the time—acting as if they’re religious and devoted to God as a way to hide their bad deeds.

[aside] Oh, ’tis too true! How smart a lash that speech doth give my conscience! The harlot’s cheek, beautied with plastering art, Is not more ugly to the thing that helps it Than is my deed to my most painted word. O heavy burden!

[To himself] Oh, that's all too true! His words are like a whip against my conscience! The whore’s ugly cheek—only made beautiful with make-up—is no more terrible than the things I’ve done and hidden with fine words. Oh, what guilt!

I hear him coming. Let’s withdraw, my lord.

I hear him coming. Quick, let’s hide, my lord.

CLAUDIUS and POLONIUS hide.

HAMLET enters.

To be, or not to be? That is the question— Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And, by opposing, end them? To die, to sleep— No more—and by a sleep to say we end The heartache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to—’tis a consummation Devoutly to be wished! To die, to sleep. To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub, For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause. There’s the respect That makes calamity of so long life. For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay, The insolence of office, and the spurns That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscovered country from whose bourn No traveler returns, puzzles the will And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all, And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pitch and moment With this regard their currents turn awry, And lose the name of action. —Soft you now, The fair Ophelia! —Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins remembered.

To live, or to die? That is the question. Is it nobler to suffer through all the terrible things fate throws at you, or to fight off your troubles, and, in doing so, end them completely? To die, to sleep—because that’s all dying is—and by a sleep I mean an end to all the heartache and the thousand injuries that we are vulnerable to—that’s an end to be wished for! To die, to sleep. To sleep, perhaps to dream—yes, but there’s there’s the catch. Because the kinds of dreams that might come in that sleep of death—after you have left behind your mortal body—are something to make you anxious. That’s the consideration that makes us suffer the calamities of life for so long. Because who would bear all the trials and tribulations of time—the oppression of the powerful, the insults from arrogant men, the pangs of unrequited love, the slowness of justice, the disrespect of people in office, and the general abuse of good people by bad—when you could just settle all your debts using nothing more than an unsheathed dagger? Who would bear his burdens, and grunt and sweat through a tiring life, if they weren’t frightened of what might happen after death—that undiscovered country from which no visitor returns, which we wonder about and which makes us prefer the troubles we know rather than fly off to face the ones we don’t? Thus, the fear of death makes us all cowards, and our natural willingness to act is made weak by too much thinking. Actions of great urgency and importance get thrown off course because of this sort of thinking, and they cease to be actions at all. But wait, here is the beautiful Ophelia!

[To OPHELIA] Beauty, may you forgive all my sins in your prayers.

Good my lord, How does your honor for this many a day?

My good lord, how have you been doing these last few days?

I humbly thank you. Well, well, well.

Thank you for asking. Well, well, well.

My lord, I have remembrances of yours That I have longèd long to redeliver. I pray you now receive them.

My lord, I have some mementos of yours that I’ve been wanting to return to you for a while. Please take them back.

No, not I. I never gave you aught.

No, it wasn’t me. I never gave you anything.

My honored lord, you know right well you did, And with them, words of so sweet breath composed As made the things more rich. Their perfume lost, Take these again, for to the noble mind Rich gifts wax poor when givers prove unkind. There, my lord.

My honorable lord, you know very well that you did. And along with these gifts, you wrote letters with words so sweet that they made the gifts seem even more valuable. But now the joy they brought me is gone, so please take them back. Beautiful gifts lose their value when the givers turn out to be unkind. There, my lord.

Ha, ha, are you honest?

Ha ha, are you pure?

Are you fair?

Are you beautiful?

What means your lordship?

What do you mean?

That if you be honest and fair, your honesty should admit no discourse to your beauty.

That if you’re pure and beautiful, your purity should be unconnected to your beauty.

Could beauty, my lord, have better commerce than with honesty?

But, my lord, could beauty be related to anything better than purity?

Ay, truly, for the power of beauty will sooner transform honesty from what it is to a bawd than the force of honesty can translate beauty into his likeness. This was sometime a paradox, but now the time gives it proof. I did love you once.

Yes, definitely, because the power of beauty is more likely to change a good girl into a whore than the power of purity is likely to change a beautiful girl into a virgin. This used to be a great puzzle, but now I’ve solved it. I used to love you.

Indeed, my lord, you made me believe so.

Yes, my lord, you made me believe you did.

You should not have believed me, for virtue cannot so inoculate our old stock but we shall relish of it. I loved you not.

You shouldn’t have believed me. No matter how hard we try to be virtuous, our natural sinfulness will always come out in the end. I didn’t love you.

I was the more deceived.

I fell for your trick, then.

Get thee to a nunnery. Why wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners? I am myself indifferent honest, but yet I could accuse me of such things that it were better my mother had not borne me. I am very proud, revengeful, ambitious, with more offences at my beck than I have thoughts to put them in, imagination to give them shape, or time to act them in. What should such fellows as I do crawling between earth and heaven? We are arrant knaves, all. Believe none of us. Go thy ways to a nunnery. Where’s your father?

Go to a convent . Why would you want to give birth to sinners? I’m as good as the next man, and yet I could accuse myself of such horrible crimes that it would’ve been better if my mother had never given birth to me. I’m arrogant, vengeful, ambitious, and have more criminal desires than I have thoughts or imagination to fit them in—or time in which to commit them. Why should people like me be allowed to crawl between heaven and earth? We’re all absolute criminals. Don’t believe any of us. Get yourself to to a convent. Where’s your father?

At home, my lord.

He’s at home, my lord.

Let the doors be shut upon him, that he may play the fool no where but in ’s own house. Farewell.

May he get locked in, so he can play the fool in his own home only. Goodbye.

O, help him, you sweet heavens!

Oh, dear God, please help him!

If thou dost marry, I’ll give thee this plague for thy dowry. Be thou as chaste as ice, as pure as snow, thou shalt not escape calumny. Get thee to a nunnery, go. Farewell. Or, if thou wilt needs marry, marry a fool, for wise men know well enough what monsters you make of them. To a nunnery, go, and quickly too. Farewell.

If you marry, I’ll give you this curse as your wedding present—even if you are as clean as ice, as pure as snow, you’ll still get a bad reputation. Get yourself to a convent, now. Goodbye. Or if you must get married, marry a fool, because wise men know that women will eventually cheat on them. Goodbye.

Heavenly powers, restore him!

Dear God, make him sane again!

I have heard of your paintings too, well enough. God has given you one face and you make yourselves another. You jig and amble, and you lisp, you nickname God’s creatures and make your wantonness your ignorance. Go to, I’ll no more on ’t. It hath made me mad. I say, we will have no more marriages. Those that are married already, all but one, shall live. The rest shall keep as they are. To a nunnery, go.

And I know all about you women and your make-up. God gives you one face, but you use make-up to give yourself another. You dance and sway as you walk, and talk in a cutesy way. You call God’s creations by pet names, and claim you don’t realize you’re being seductive. No more. I won’t allow it anymore. It has made me angry. I proclaim: we will have no more marriages. Of those who are married already—all but one person—will live on as couples. Everyone else will have to stay single. Go to a convent.

HAMLET exits.

Oh, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown!— The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s, eye, tongue, sword, Th’ expectancy and rose of the fair state, The glass of fashion and the mould of form, Th’ observed of all observers, quite, quite down! And I, of ladies most deject and wretched, That sucked the honey of his music vows, Now see that noble and most sovereign reason Like sweet bells jangled, out of tune and harsh; That unmatched form and feature of blown youth Blasted with ecstasy. Oh, woe is me, T’ have seen what I have seen, see what I see!

Oh, his great mind has been overcome by insanity! He had a courtier’s persuasiveness, a soldier’s courage, a scholar’s wisdom. He was the perfect rose and great hope of our country—the model of good manners, the trendsetter, the center of attention. Now he’s fallen so low! I am the most miserable of all the women who once enjoyed hearing his sweet words. A once noble and disciplined mind that sang sweetly is now harsh and out of tune. The unmatched beauty he had in the full bloom of his youth has been destroyed by madness. Oh, poor me, to have seen Hamlet as he was, and now to see him in this way!

CLAUDIUS and POLONIUS come forward.

Love? His affections do not that way tend. Nor what he spake, though it lacked form a little, Was not like madness. There’s something in his soul O’er which his melancholy sits on brood, And I do doubt the hatch and the disclose Will be some danger —which for to prevent, I have in quick determination Thus set it down: he shall with speed to England For the demand of our neglected tribute. Haply the seas and countries different With variable objects shall expel This something-settled matter in his heart, Whereon his brains still beating puts him thus From fashion of himself. What think you on ’t?

Love? His feelings don’t move in that direction. And his words—although they were a bit all over the place—weren’t crazy. No, his sadness is like a bird sitting on an egg. And I think that whatever hatches is going to be dangerous. To prevent that danger, I’ve made a quick decision: he’ll be sent to England to try to get back the tribute money they owe to us. Hopefully the sea and all the new things to see in a different country will push out these thoughts that have somehow taken root in his mind, making him a stranger to his former self. What do you think?

It shall do well. But yet do I believe The origin and commencement of his grief Sprung from neglected love. —How now, Ophelia? You need not tell us what Lord Hamlet said. We heard it all. —My lord, do as you please. But, if you hold it fit, after the play Let his queen mother all alone entreat him To show his grief. Let her be round with him, And I’ll be placed, so please you, in the ear Of all their conference. If she find him not, To England send him or confine him where Your wisdom best shall think.

It should work. But I still think that the cause of his madness was unrequited love.

[To OPHELIA] Hello, Ophelia. You don’t have to tell us what Lord Hamlet said. We heard it all.

[To CLAUDIUS] My lord, do whatever you like. But, if you think it’s a good idea, after the play let his mother the queen get him alone and beg him to share the source of his grief. She should be blunt with him. Meanwhile, if you think it’s all right, I’ll hide and listen to what they say. If she can’t find the source of his madness, send him to England or confine him wherever you think best.

It shall be so. Madness in great ones must not unwatched go.

That’s what we’ll do. Madness in important people must be closely watched.

They all exit.

The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

Program code and database © 2003-2024 George Mason University . All texts are in the public domain and can be used freely for any purpose. Privacy policy

- Works Plays Play Synopses Poetry A Shakespeare Timeline Study Resources Authorship

- Life Biography Shakespeare's Will

- Historical Elizabethan England Historical Scholarship The Globe Shakespeare's Language

- Performance Scenes and Monologues Theatre Companies

- SRC Features Articles and Features Shakespeare's Grammar Speech Analysis Blogs and Podcasts Reading List Other Links Ask the Bard!

- Site Info About Us Contact Us Copyright Notice Privacy Policy Site Map

Hamlet "To be or not to be...."

Overview | Readings Page | Home

The opening line scans fairly normally, and the stresses help emphasize the comparison of being versus not being. The line is an example of a feminine ending , or a weak extra syllable at the end of the line. Hamlet puts forth his thesis statement at the beginning of his argument, which is generally a good idea. Be here is used in its definition of "exist." Note the colons signifying two caesuras (pauses) in the opening line. The trochee of that is works in two ways here, lending proper emphasis to the line and reinforcing the pause in the middle.

The initial trochee is a typical inversion of Shakespeare's; beginning the line with a stressed syllable varies the rhythm and gives a natural emphasis at the start. The third foot with "in" could also be scanned as a pyrrhic . Hamlet now elaborates on his proposition; the question actually concerns existence when faced with suffering. Nobler here seems most likely to denote "dignified," in the mind translates to "of opinion," and suffer is used in the sense "to bear with patience or constancy." As a whole, a thoroughly less poetic rendering of the line translates to "whether people think that it's more dignified to put up with."

This is the third feminine ending in a row, and it's hard to overlook as anything but a conscious effort. Some editors have argued that the original word was "stings" rather than "slings," although slings and arrows makes for a better rhetorical construction. Slings and arrows imply missile weapons that can not only strike from a distance but can miss their mark and strike someone unintended. That would fit with the capriciousness suggested by the phrase outrageous fortune . The metaphor also brings up the demoralizing aspect of enduring attacks without being able to respond effectively—whether from archers, snipers, artillery, or even guerrilla tactics. Outrageous in this speech denotes "violent or atrocious." In this usage, fortune denotes "the good or ill that befalls man."

Here's a changeup: a pyrrhic followed by a spondee that adds a natural emphasis on take arms (denoting in this instance to "make war"). In what follows, we have straight iambic meter with yet another feminine ending . The initial quatrain of four weak endings could be an attempt by Shakespeare to use the verse to convey further Hamlet's uncertainty. Sea of troubles is a fairly simple metaphor in this usage that compares Hamlet's troubles (sufferings) to the vast and seemingly boundless sea. This line essentially translates to "or to fight against the endless suffering." The preceding reference to "outrageous fortune" dictates that Hamlet is primarily referring to the continuous assault of troubles that he perceives life as presenting him. However, the double entendre is whether to take up arms against the external troubles (i.e., Claudius) or against those troubles within himself (thus implying consideration of suicide). Either way, Hamlet seems to be asking if the struggle is even worth the effort.

The line would appear to scan as iambic pentameter with an extra unstressed syllable preceding the implied pause after "them?" (a pause, incidentally, that makes it hard to scan "...them? To die" as an anapest foot, since the two unstressed syllables don't run together.) The use of opposing in context continues the metaphor of armed struggle begun by "take arms" in the previous line. There is potential ambiguity in the use of die here; obviously, it means "to lose one's life," but there are possible secondary meanings of "to pine for" and "vanish" as well. Sleep plays upon a double meaning of both "rest" and "being idle or oblivious."

You could scan the first foot as either an iamb or a spondee ; I've chosen a spondee because it seems like "No more" is a singular concept that warrants equal weight on the two syllables. There's a natural pause that comes before "and by a sleep...." The line is basically a qualifier of Hamlet's usage of "sleep" in the line before.

Scansion here reveals a possible anapest at the end of the line (if one doesn't treat the next-to-last word as "nat'ral"). This line serves as poetic elaboration of the "sea of troubles" to which Hamlet refers earlier. Heart-ache is easily enough understood as anguish or sorrow, while thousand signifies "numerous" in this context, and natural shocks translates loosely to "normal conflicts."

That flesh is heir to is a poetic way of saying "that afflict us" (literally "that our bodies inherit"). Consummation (Middle English: consummaten from the Latin consummare , "to complete or bring to perfection") is a poetic usage that plays off its traditional meaning to mean "end" or "death."

Let it be noted that this repetition of "to die, to sleep" is an intentional rhetorical device. The significance of using the same phrase in a focal position at the end of two lines makes it nearly impossible to speak this speech without emphasizing the death/sleep comparison at work. Here, devoutly denotes a meaning of "earnestness" rather than its more traditional religious association; this speech, unlike Hamlet's first soliloquy, is secular rationalism (especially in contrast with "Or that the Everlasting had not fix'd/His canon 'gainst self-slaughter! O God! God!").

The spondee in the fourth foot helps to punch the change that "perchance to dream" brings into the speech. Metrically, you can hear Hamlet working through the logic based on the stresses. Rub means "obstacle or impediment," and perchance means "perhaps" in context. The point of this line is that Hamlet seeks oblivion, which he has likened to a deep slumber. However, the flaw in this thinking, as Hamlet reasons out, is that dreams come to us during sleep. One can imagine that Hamlet's dreams are reasonably unpleasant, which leads him to extrapolate in the next line....

Notice how the straight iambic rhythm of this line and the one that follows quickens the pace of Hamlet's speech. This is reinforced by a lack of pauses (think about how colons, semicolons, and commas act as linguistic speed bumps in some of the previous lines). Now the rhetorical comparison of sleep and death is driven home, and Hamlet infers that if death is sleep intensified, then the possible dreams in death are likely to be intensified as well.

Again, the uninterrupted iambic pentameter is skipping toward the predicate of Hamlet's discovery (which occurs in the next line). The language here, of course, is Shakespeare's poetic way of saying "when we've died" ( shuffled = "gotten rid of" and coil = "turmoil, confusion").

Scansion here reveals a trait that Shakespeare sometimes uses in a mid-line caesura : he occasionally eliminates a syllable or an entire foot following the pause. In this case, the line is only eight total syllables. Some scholars point out that at least some of these syllabic irregularities might also be due to corruptions of the text over 400 years. Must give us pause is the predicate of "dreams" from two lines prior. This line is also an example where the language can help the performer; just try to gloss over the word "pause" in this line. It's impossible. The verse, the punctuation, the context, and the word itself all serve to force the speaker to take some form of pause before moving on. Give us pause in context denotes "stop and consider." The usage of respect here denotes "a reason or motive."

My scansion pattern in this line is based on the sense of the speech. "Makes" is the predicate of this clause and needs a certain amount of stress. Although it might ordinarily seem strange in another context, the ending with three stressed syllables on "so long life" works because the back-to-back stresses draw out the words in an onomatopoetic manner (think about how your own speech might drag if you were describing something that tired you out just thinking about it). The word calamity is used in the sense of "misery."

This plain iambic line begins a five-line poetic laundry list of examples of all those things that make life such a burden. Keep in mind that this is an extended, slightly rhetorical question Hamlet poses. The subject—those who would bear—begins in this line. The whips and scorns of time refers more to Hamlet's (or a person's) lifetime than to time as a figurative reference of eternity.

Fans of subjective scansion should love this line. Is the opening foot a pyrrhic , an anapest , or an iamb formed by pronouncing the beginning almost like "th'oppressor"? Contumely (contemptuous treatment or taunts, from the Middle English contumelie from the Latin contumelia , meaning "abuse, insult") scans in this context as three syllables rather than four. This scansion gives the line an iambic feel (albeit with the flavor of a feminine ending), and the most logical way of viewing the meter seems to be: anapest / iamb / iamb / iamb / pyrrhic . At least that makes the line predominantly iambic pentameter .

This line is more interesting for its rhetorical devices than its metrical pattern. Like the line prior, there is a mid-line caesura that creates an internal parallel structure. Note the play of consonance in juxtaposing disprized love and law's delay , as well as the light "s" sounds that punctuate several points within the line.

The fourth foot could scan as an iamb rather than a pyrrhic , but that's quibbling. This line produces heavy consonance with the words insolence (rudeness, impudence; from the Latin insolens , meaning "immoderate" or "overbearing") office (public officials), and spurns (insults). Incidentally, this in a nutshell is why Shakespeare still works for us four centuries later: the gripe of the public against those who hold public office is both universal and eternal.

There are quite a few things going on here. First, scansion reveals as many as four unstressed syllables in a row, which is unusual. The line itself is 11 syllables; as scanned above, the line can be described as iamb / iamb / pyrrhic / anapest / iamb . Scanning "of" as stressed (however slightly) turns that interpretation into iamb / iamb / iamb / anapest / iamb instead. Grammatically, this line is an object-subject-verb inversion with the direct object ("spurns") on the previous line, which makes it all a bit dicier to parse. Patient in this context is defined as "bearing evils with calmness and fortitude," while merit denotes "worthiness" and takes is used as "receives." Literally, the clause would translate to something like "the insults that worthy fortitude receives from the unworthy."

Now that Hamlet is done listing all those "whips and scorns of time," he's getting to the heart of his proposition. Who would suffer all this when there's another choice? Here's a bit of trivia: Shakespeare uses quietus only twice in all his works (the other occurrence is in Sonnet 126). It comes originally from Medieval Latin, meaning "at rest." In Middle English, it took on the denotation "discharge of obligation" and here denotes "release, or settlement of account." It is Shakespeare's poetic license in this speech that produces the contemporary meaning of "a release from life." That being said, it is the older interpretation of "quietus" that leads some scholars to argue that the whole point of this soliloquy is Hamlet talking about "settling his debt" with Claudius. It's the sort of thing that leads to academic "flame wars," so there's something to be said for the entertainment value.

Bare bodkin is the salient point (no pun intended) of this line, so it gets the stresses. This creates a pyrrhic / spondee / iamb / iamb / iamb rhythm. Bodkin at the time meant a sharp instrument, much like an awl, used for punching holes in leather. In this context, it suggests a dagger or stiletto (think of the phrase as resembling "bare blade"). The word derives from the Middle English "boidekin." Hamlet is basically asking who wants to suffer life when you could end your troubles with a dagger. After the initial question, Hamlet continues by asking who would bear fardels (pack, burden; from Middle English via Middle French, likely originally from the Arabic fardah ).

There is little noteworthy revealed in the scansion; the stresses fall on the words you would expect to hear stressed. Samuel Johnson preferred " groan and sweat" in his 1765 edition of the works, annotating, "All the old copies have, 'to grunt and sweat'. It is undoubtedly the true reading, but can scarcely be borne by modern ears." Weary here means "tiresome."

This plain blank verse clause refers back to the fardel-bearing "who" of two lines prior. Dread (Middle English = dreden , from the Old English adrædan meaning "to advise against") is used in its primary meaning of "fear," although its archaic meaning of "awe or reverence" could be in play as well. Primarily, however, the point is that fear of the unknown is possibly the only thing keeping man from killing himself to end his troubles.

With regard to meter, the only real question here is whether to stress from , whose , both, or neither. The undiscover'd country is a poetic reference to death; bourn denotes "limit, confine, or boundary." Bourn derives either from the Old English burna meaning "stream or brook" (via Old High German brunno , meaning "spring of water") or, alternately, from the French bourne (via Old French bodne , meaning "boundary or marker"), depending upon which etymologist you want to believe. With England having been prominently invaded by both Germanic and French speakers, either influence (or both) could be at work.

The rhythm here gets a little disjointed, scanning as spondee / pyrrhic / iamb / trochee / iamb . Puzzles denotes "perplexes or embarrasses," and will (from Middle English via Old English willa , meaning "desire") denotes "intellect or mind." What is most curious to both the casual reader and scholar alike is the statement Hamlet makes that no one returns from death—after he has been visited by his father's ghost. Perhaps Hamlet means no living being returns, or perhaps this thought betrays Hamlet's doubts that the spirit was truly his father. Or—if one interprets Hamlet as making this speech for the benefit of Claudius and Polonius—perhaps Hamlet wants to mislead any eavesdroppers precisely because of the ghost's appearance. There are any number of theories about this, including the hypothesis that the entire monologue or scene has been misplaced in the text. Invent your own explanation—it's fun, and it may earn you a research grant.

Did you know that ill derives from an Old Norse word meaning "bad"? The entire point of this purely iambic line is to set up a comparison between the devil we know...

...and the devil we don't. What Hamlet says in effect is that fear of the unknown binds us all (in this case, fear of that unknown beyond death's door). As bad as earthly suffering is, there could be far worse in store for us in death. This is especially true for those who would commit suicide, which was viewed as an abomination by the Church (who saw it as one of the gravest affronts to God) and a guaranteed path to Hell—both by virtue of the sin itself and the Church's refusal to give the offender proper burial rites. Though the speech doesn't directly invoke God, this has to be an undercurrent, no matter how rationally and philosophically Hamlet couches it.

Thus in this line scans as a stress (making the first foot a spondee rather than an iamb ) primarily because of the end-stop of the line above. It also gives emphasis to the slight turn of the speech into its conclusion. Conscience (Middle English via Old French, from Latin conscientia , "to be conscious") here is used primarily in its older sense of "consciousness, inmost thought or private judgment" rather than implying a moral dilemma. The premise is that thoughts can deter action, not unlike the conclusion of Macbeth's dagger soliloquy.

This line sets up the contrast between resolution and thought using a parallelism ( native hue vs. pale cast ). Native is used in its sense of "natural"; native hue implies a bold, healthy color symbolizing determination.

The antithesis of healthy determination, in this comparison, is the affliction of thought. Sicklied o'er denotes "tainted," and cast denotes "tinge or coloration." Hamlet, in these two lines, hits upon the dramatic problem (and arguably his own tragic flaw) of the play.

Enterprises (from the Old French entreprendre , "to undertake") denotes undertakings. Pith derives from the Old English pitha (via Old German pith ), which originally denoted the core of a fruit—as in a peach's pit—and evolved into a figurative meaning of spinal cord or bone marrow; here pith demonstrates its evolved denotation of "strength or vigor." Moment , while it might seem to indicate timeliness, actually denotes "consequence, importance" in this context.

This is a line in which the unvaried iambic pentameter combined with the consonance of the prevalent "r" sounds propel the speaker toward the conclusion of Hamlet's speech. Regard denotes "consideration" in its usage, while currents is a metaphor based on its meaning "the flowing [steady] motion of water." With turn (change direction) and awry (obliquely, askew), the line loosely translates to "are disrupted by thinking about them."

The line continues after "action" with Ophelia's appearance, scanning as a full line of iambic pentameter . Compare this conclusion with the end of the dagger soliloquy of Macbeth ("Words to the heat of deeds too cold breath gives"). Here, Hamlet is making a similar statement, that giving too much thought to the consequences of important actions can paralyze us.

Go to Overview | Back to Readings

Copyright © 1997–2023, J. M. Pressley and the Shakespeare Resource Center Contact Us | Privacy policy

Hamlet: ‘To Be Or Not To Be, That Is The Question’

‘ To be or not to be , that is the question’ is the most famous soliloquy in the works of Shakespeare – quite possibly the most famous soliloquy in literature. Read Hamlet’s famous soliloquy below with a modern translation and full explanation of the meaning of ‘To be or not to be’. We’ve also pulled together a bunch of commonly asked questions about Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, and have a couple of top performances of the soliloquy to watch.

Jump to section: Full soliloquy | Analysis | Performances | FAQs | Final read

Let’s start with a read-through of Shakespeare’s original lines:

Hamlet’s ‘To Be Or Not To Be’ Speech, Act 3 Scene 1

To be, or not to be: that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune , Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them? To die: to sleep; No more; and by a sleep to say we end The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks That flesh is heir to, ’tis a consummation Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep; To sleep: perchance to dream : ay, there’s the rub; For in that sleep of death what dreams may come When we have shuffled off this mortal coil, Must give us pause: there’s the respect That makes calamity of so long life; For who would bear the whips and scorns of time, The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay, The insolence of office and the spurns That patient merit of the unworthy takes, When he himself might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear, To grunt and sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The undiscover’d country from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the will And makes us rather bear those ills we have Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us all; And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their currents turn awry, And lose the name of action.–Soft you now! The fair Ophelia! Nymph, in thy orisons Be all my sins remember’d.

Hamlet ‘To Be Or Not To Be’ Analysis

Hamlet is thinking about life and death. It is the great question that Hamlet is asking about human existence in general and his own existence in particular – a reflection on whether it’s better to be alive or to be dead.

The in-depth version

The first six words of the soliloquy establish a balance. There is a direct opposition – to be, or not to be. Hamlet is thinking about life and death and pondering a state of being versus a state of not being – being alive and being dead.

The balance continues with a consideration of the way one deals with life and death. Life is a lack of power: the living are at the mercy of the blows of outrageous fortune. The only action one can take against the things he lists among those blows is to end one’s life. That’s the only way of opposing them. The ‘sleep of death’ is therefore empowering: killing oneself is a way of taking action, taking up arms, opposing and defeating the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Living is a passive state; dying is an active state. But in order to reach the condition of death one has to take action in life – charge fully armed against Fortune – so the whole proposition is circular and hopeless because one does not really have the power of action in life.

Death is something desirable – devoutly to be wished, a consummation – a perfect closure. It’s nothing more than a sleep. But there’s a catch, which Hamlet calls a rub. A ‘rub’ is a bowls term meaning an obstacle on the bowls lawn that diverts the bowl, so the fear of the life hereafter is the obstacle that makes us pause and perhaps change the direction of our thinking. We don’t control our dreams so what dreams may come in that sleep in which we have shuffled off all the fuss and bother of life? He uses the term ‘ mortal coil ,’ which is an Elizabethan word for a big fuss, such as there may be in the preparations for a party or a wedding – a lot of things going on and a lot of rushing about. With that thought, Hamlet stops to reconsider. What will happen when we have discarded all the hustle and bustle of life? The problem with the proposition is that the sleep of death is unknown and could be worse than life.

And now Hamlet reflects on a final end. A ‘quietus’ is a legal word meaning a final definitive end to an argument. He opposes this Latin word against the Celtic ‘sweating’ and ‘grunting’ of a living person as an Arab beneath an overwhelmingly heavy load – a fardel, the load carried by a camel. Who would bear that when he could just draw a line under life with something as simple as a knitting needle – a bodkin? It’s quite a big thought and it’s fascinating that this enormous act – drawing a line under life – can be done with something as simple as a knitting needle. And how easy that seems.

Hamlet now lets his imagination wander on the subject of the voyages of discovery and the exploratory expeditions. Dying is like crossing the border between known and unknown geography. One is likely to be lost in that unmapped place, from which one would never return. The implication is that there may be unimagined horrors in that land.

Hamlet now seems to make a decision. He makes the profound judgment that ‘conscience does make cowards of us all,’ This sentence is probably the most important one in the soliloquy. There is a religious dimension to it as it is a sin to take one’s life. So with that added dimension, the fear of the unknown after death is intensified.

But there is more to it than that. It is not just about killing himself but also about the mission he is on – to avenge his father’s death by killing his father’s murderer. Throughout the action of the play, he makes excuses for not killing him and turns away when he has the chance. ‘Conscience does make cowards of us all.’ Convention demands that he kill Claudius but murder is a sin and that conflict is the core of the play.

At the end of the soliloquy, he pulls himself out of this reflective mode by deciding that too much thinking about it is the thing that will prevent the action he has to rise to.

This is not entirely a moment of possible suicide. It’s not that he’s contemplating suicide as much as reflecting on life, and we find that theme all through the text. In this soliloquy, life is burdensome and devoid of power. In another, it’s ‘weary, stale, flat and unprofitable,’ like a garden overrun with weeds. In this soliloquy, Hamlet gives a list of all the things that annoy him about life: the whips and scorns of time, the oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, the pangs of despised love, the law’s delay, t he insolence of office and the spurns t hat patient merit of the unworthy takes. But there’s a sense of agonized frustration in this soliloquy that however bad life is we’re prevented from doing anything about it by fear of the unknown.

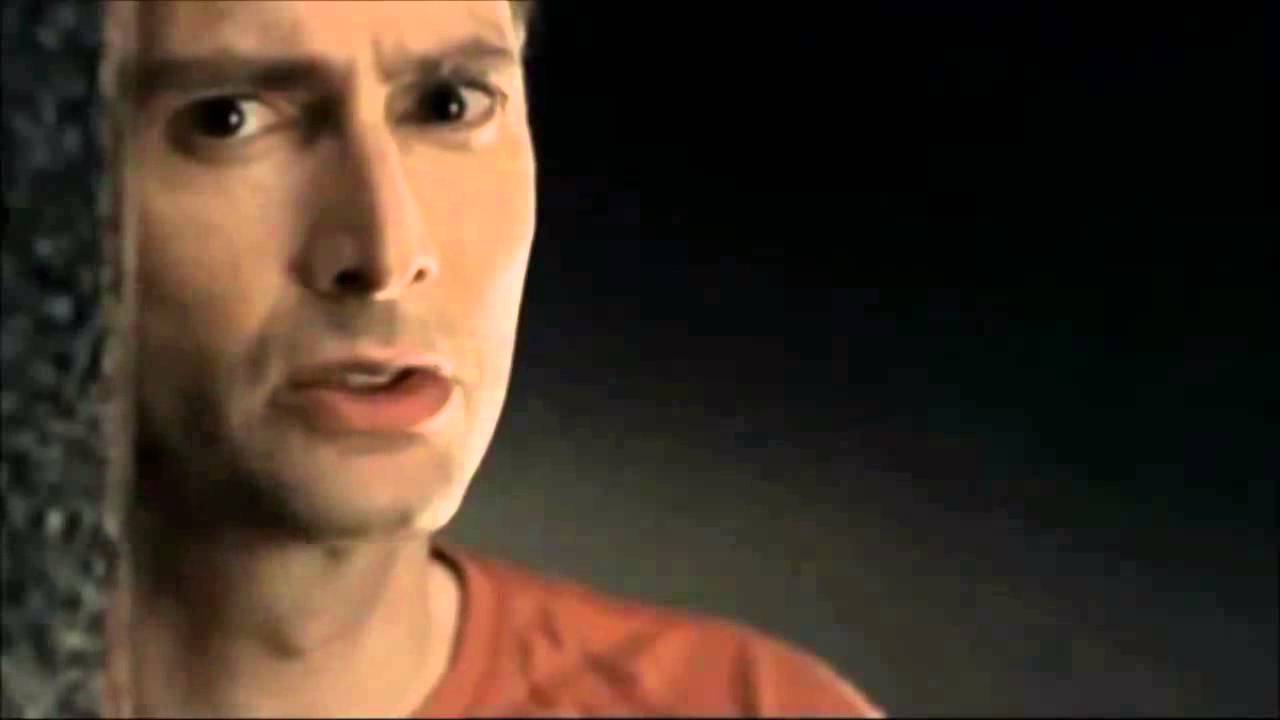

Watch Two Theatre Greats Recite Hamlet’s Soliloquy

David Tenant as Hamlet in the RSC’s 2009 Hamlet production:

We couldn’t resist but share Patrick Stewart’s comedy take on the soliloquy for Sesame Street!

Commonly Asked Questions About ‘To Be Or Not To Be’

Why is hamlet’s ‘to be or not to be’ speech so famous.

This is partly because the opening words are so interesting, memorable and intriguing, but also because Shakespeare ranges around several cultures and practices to borrow the language for his images. Just look at how many now-famous phrases are used in the speech – ‘take arms’, ‘what dreams may come’, ‘sea of troubles’, ‘to sleep perchance to dream’. ‘sleep of death’, ‘whether tis nobler’, ‘flesh is heir’, ‘must give us pause’, ‘mortal coil’, ‘suffer the slings and arrows’, outrageous fortune’, ‘the insolence of office’… the list goes on and on.

Add to this the fact that Shakespeare is dealing with profound concepts, putting complex philosophical ideas into the mouth of a character on a stage, and communicating with an audience with a wide range of educational levels, and you have a selection of reasons as to why this soliloquy is as famous as it is. Just look at how many now phrases

How long is ‘To be or not to be’?

The ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy is 33 lines long, and consists of 262 words. Hamlet, the play in which ‘to be or not to be’ occurs is Shakespeare’s longest play with 4,042 lines. It takes four hours to perform Hamlet on the stage, with the ‘to be or not to be’ soliloquy taking anywhere from two to four minutes.

Why is ‘To be or not to be’ so important?

‘To be or not to be’ is not important in itself but it has gained tremendous significance in that it is perhaps the most famous phrase in all the words of the playwright considered to be the greatest writer in the English language. It is also significant in the play, Hamlet , itself in that it goes directly to the heart of the play’s meaning.

Why does Hamlet say ‘To be or not to be’?

To be or not to be’ is a soliloquy of Hamlet’s – meaning that although he is speaking aloud to the audience none of the other characters can hear him. Soliloquies were a convention of Elizabethan plays where characters spoke their thoughts to the audience. Hamlet says ‘To be or not to be’ because he is questioning the value of life and asking himself whether it’s worthwhile hanging in there. He is extremely depressed at this point and fed up with everything in the world around him, and he is contemplating putting an end to himself.

Is ‘To be or not to be’ a metaphor?

The line ‘To be or not to be’ is very straightforward and direct, and has no metaphorical aspect at all. It’s a simple statement made up of five two-letter words and one of three – it’s so simple that a child in the early stages of learning to read can read it. Together with the sentence that follows it – ‘that is the question – it is a simple question about human existence. The rest of the soliloquy goes on to use a number of metaphors.

What is Shakespeare saying in ‘To be or not to be’?

In the ‘To be or not be to’ soliloquy Shakespeare has his Hamlet character speak theses famous lines. Hamlet is wondering whether he should continue to be, meaning to exist or remain alive, or to not exist – in other words, commit suicide. His thoughts about that develop in the rest of the soliloquy.

Why is ‘To be or not to be’ so memorable?

Ask people to quote a line of Shakespeare and more often than not it’s ‘To be or not to be’ that’s mentioned. So just what is it that makes this line of Shakespeare’s so memorable?

The line is what is known as a chiasmus because of its balance and structure, and that’s what makes it memorable. Look at this chiasmus from John F Kennedy: ‘Do not ask what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.’ Far more complex than Shakespeare’s line but even so, having heard it one could never forget it. The first and second halves mirror each other, the second being an inversion of the first. Winston Churchill’s speeches are full of chiasma. Even when he is joking they flow: ‘All babies look like me, but then I look like all babies.’

Chiasma are always short and snappy and say a lot in their repetition of words and their balance. And so it is with Hamlet’s speech that starts ‘to be or not to be’, arguably Shakespeare’s most memorable line – in the collective conscience centuries after the words were written and performed.

Look at the balance of the line. It has only four words: ‘to,’ ‘be,’ ‘or’ and ‘not.’ The fact is that the language is as simple as language can get but the ideas are extremely profound. ‘To take arms against a sea of troubles,’ for example, and ‘To die, to sleep, no more, but in that sleep of death what dreams may come,’ every word but one monosyllabic, go right to the heart of human existence and the deepest dilemmas of life.

Let’s try reading it again…

If you’re still with us, you should now have a pretty good understanding of the true meaning behind the words of Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’ speech. You may have also watched two fantastic actors speak the immortal words, so should have a much clearer understanding of what messages the soliloquy is trying to convey.

With all of this in mind, why not try reading the words aloud to yourself one more time:

David Tennant speaks Hamlet’s ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy

And that’s all for this take on Hamlet’s immortal lines. Did this page help you? Any information we’re missing that would be useful? Please do let us know in the comments section below!

- Total 1,064

- Twitter 289

- WhatsApp 55

- Pinterest 0

I apologise for the small gripe, but since when did ‘sweating’ and ‘grunting’ become ‘Celtic’ words?

Both words are of Proto-Germanic origin, and Proto-Celt along with Proto-Germanic are considered to be of Indo-European in origin. Which is different than being Latin in origin. I would assume that perhaps they made an error in mentioning they were Celtic in origin instead of Germanic.

I’ve seen a theatrical “King Lear “ recently, and noticed with surprise that there is a soliloquy of “ to be or not to be “ from Hamlet. Is it a free interpretation of the director or is it a real citation from Hamlet? Thank you very much

I appreciate the clear explanation with background you give! Great job!

Thank You. These words remind me that all lives are lived with burdens perceived that don’t always become our realities.At the same time they are encouraging as we move out of shadows into light.

This is where Albert Camus gets the opening lines of “The Myth of Sisyphus.” He writes, The whole question of philosophy is the question of suicide.

Or, as the ancient Greeks had it; ‘ the greatest gift the gods have given to man is that he may end his life when he will’. But I prefer ‘ eat drink and be merry for tomorrow we die’; 91 soon so each day is a bonus. Wouldn’t be dead for quids !

Thank you, it was as much as I wanted and not more than I needed.

I gotta memorize this for AP English and man I HATE IT!!! Hamlet needs to stop being a little crybaby and just DO IT already!!!!!

Not a bad summary but some mistakes. 1) The first line is not a chiasmus: in a chiasmus, as you correctly illustrate, each part has two elements and they swap places. 2) Hamlet is not debating whether HE should continue to be as the speech is completely impersonal. 3) The idea that he is depressed, and indeed that the speech is a soliloquy, are guesses supported only by post-Renaissance sentimental theatrical tradition, which has sentimentalised the character. Neither you nor anyone else has found a clear meaning in the speech, and since we don’t know what he’s saying we don’t know why he says it. Moreover, the utter impersonality and detachment of the speech suggest rather that it is NOT a soliloquy.

I agree with these comments. I am not satisfied with either the analysis of the writer nor with the later comment that Hamlet is a weak ‘cry baby’ It is a reflective speech not one seeking a decision. He is not choosing, he is considering the inherent options, and we can generally agree with them, although in these more secular days it is the obliteration of life and subsequent oblivion that stays our hand at self-slaughter rather than some post mortem reality. An although it is legitimate to infuse a Christian flavour to Shakespeare’s use of the word ‘conscience’, I dont choose to see the use of that word as implying ‘sin’, more an attempt to avoid making an ill informed and incorrect decision, which in fact is the inherent problem Hamlet faces throughout the play. Is his uncle really guilty, is the spirit of his father benign or demonic, and all the other questions he is constantly asking. From the writer’s point of view, these questions are the tactics he chooses to use to delay the outcome. Hamlet after all is a revenge tragedy, and must needs therefore delay the resolution of the problem posed by his father’s death. Those, like one of the above commentators, who see the whole play as a series of vacillations, are also people I am sure who have never had to kill a member of their own family to avenge the murder of another.

With respect, Shakespeare, while complex, is not inscrutable. The idea that nobody knows what this means, and we can’t know what this means – is perhaps not the best way to read Shakespeare, or anything else for that matter. Shakespeare wrote plays that were meant to be seen, experienced, understood and thought deeply about. That every generation since has done this, is why he is loved, and is why he is believed to be the best to ever put pen to paper.

It seems to me that the original author might benefit from another possibility. Namely, that the question for Hamlet is not just contemplating his own life, but whether or not to directly avenge the murder of his father. To be, or not to be, is, “to avenge” or “not to avenge” which Hamlet (perhaps mistakenly) conflates with his life and existence.

If that holds, he feels that if he does not act, then his life and existence are meaningless. Everything, for Hamlet, has reduced to this moment and this singular choice.

In this mindset, the choice becomes framed as a choice to live or not live, because that is how deeply he feels compelled to act. You could argue that he is rationalizing revenge to be an act that his very life and meaningful existence depend on. When put that way, it’s not a choice at all. He must be. He must act.

The problem is, that this isn’t true. He isn’t faced with a real binary choice in this way. He has options. Hamlet could forgive. He could walk away and forge another life in exile. He could build evidence and try to make a case for private, or even public support against the king. He could raise an army and stage a coup. He could live quietly and wait out the king’s eventual mortality. There are lots of other possibilities that could be framed.

Now, those may seem like feckless choices in the face of great injustice. But imagine what would happen to society if everyone made Hamlet’s choice in every situation. If we, took the direct handling of revenge, even arguably just revenge, into our own hands – it is Hatfield and McCoys forever, with blood in our homes and in our streets. It never stops. I would argue that history clearly teaches us that revenge almost always spills outside or our control and ends up hurting people that weren’t initially involved. Hamlet made the wrong choice and it destroyed him, his family and a lot of innocent people.

Shakespeare is brilliant and complex, and my goodness can he write the most trivial detail in the most beautiful and compelling way. But on another level, he is super simple in terms of bigger picture understanding. The question to help us understand Shakespeare (especially in the tragedies) is this: read the basic events like a child would; namely what is the result of the choices made?

Macbeth – a lot of death and chaos. Is that good or bad? Bad. It may be that Shakespeare’s larger message is that MacBeth and Lady MacBeth made wrong choices in handling ambition. Romeo and Juliet – double suicide by teen / pre-teen couple over a misunderstanding. Wrong choices in handling personal romance. Hamlet – literally everyone but a single survivor dies. Wrong choices in handling revenge and societal injustice.

The “to be or not to be” monologue is showing us how Hamlet goads his own thinking into unalterable action and shows us the setting of his will onto a path that will be incredibly destructive.

Our author here, would set this up as a choice to commit suicide (not to be), or not, and the right answer would necessarily be to live (to be). The problem is, this doesn’t fit with the play, or the outcome of the play. Hamlet is not choosing to refuse suicide in a narrative vacuum. Hamlet choosing to live, also results in the death of a lot of other people. In the narrative, his choosing to live is tightly tied to the execution of his revenge. And he dies anyway.

I suppose you could make the argument that Hamlet was justified in his decision for revenge, but it went badly, because life is messy. I would argue that while life is messy, Shakespeare is not, and his clarity of vision and expression are fraught with intentionality.

And that his insight, when apprehended, leads us to see the ripple of truth and the wisdom of his subject in the real world as well, in ways which are useful and virtuous when rightly understood.

My read would be that the right answer, according to Shakespeare, is to “not be”, leaving direct vengeance to God while pursuing justice as best we can through other means.

With respect I think you have said literally nothing in all that. Get specific. If you think 2B is a soliloquy, what does he say that so desperately needs a special channel of communication to the audience and requires us to imagine the Ophelia can’t hear him despite being literally in his way and the spies can’t hear him despite having located themselves precisely in order to do so? Do you not think it’s possible that our failure to pin down what he says is related to our assumption that it’s a soliloquy?

Leave a Reply

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

See All Hamlet Resources

Hamlet | Hamlet summary | Hamlet characters : Claudius , Fortinbras , Horatio , Laertes , Ophelia . Osric , Polonius , Rosencrantz and Guildenstern | Hamlet settings | Hamlet themes | Hamlet in modern English | Hamlet full text | Modern Hamlet ebook | Hamlet for kids ebooks | Hamlet quotes | Hamlet quote translations | Hamlet monologues | Hamlet soliloquies | Hamlet performance history | All about ‘To Be Or Not To Be’

Looking to pay someone who can help with your paper on any Hamlet topic?