20th century travel

Location & hours.

Suggest an edit

Via Cassia, 638

Recommended Reviews

- 1 star rating Not good

- 2 star rating Could’ve been better

- 3 star rating OK

- 4 star rating Good

- 5 star rating Great

Select your rating

Overall rating

People Also Viewed

I Viaggi di Mafalda

Sonic Travel and Tours

Agenzia Viaggi Nomentano

Glitter Travel

Touring Express

Breeze Travel

Scire’ Viaggi

Touch & GO Viaggi e Turismo

Other Agenzie di viaggio Nearby

Find more Agenzie di viaggio near 20th century travel

Related Cost Guides

Town Car Service

20th Century Travel

Seven sites of art, history and culture just one hour from Rome

A tour at Rocca di Papa, a small town where over the centuries various legends have arisen

The Necropolises of Tarquinia and Cerveteri

The 'great beauty' of Palazzo Sacchetti, in the heart of Rome, set of the Oscar-winning film by Paolo Sorrentino

Rome is the perfect destination for sustainable tourism

Rome's Historic Cafes

The historical centre of Rome with all its beauty.

At MAXXI in Rome, data becomes matter

The works by Caravaggio in Rome

The most beautiful fashion locations to see in Rome during Fashion Week

Exclusive aperitifs in Rome's most evocative locations

The MAXXI Museum in Rome

The Vatican Museums and the Sistine Chapel, wonders second to none in the world

St. Peter's Basilica and the Vatican Museums

Rome in 7 stages: on the sets of the TV series Skam Italia, the everyday life of people in Rome

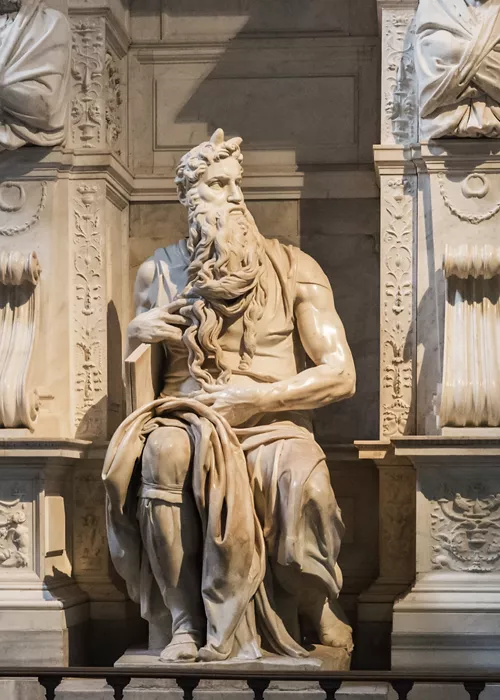

Michelangelo's Moses at San Pietro in Vincoli

5 unusual things to see in Rome, sacred and profane

The Catacombs of Rome

Rome: The Imperial Fora

2 days in Rome: the itinerary

Rock in Roma 2024

Golden Gala

2024 ITTF WORLD MASTERS TABLE TENNIS CHAMPIONSHIPS

The unique feast of Santa Rosa in Viterbo

Save your favorite places.

Create an account or log in to save your wishlist

Do you already have an account? Sign in

A Magical 3 Days in Rome Itinerary

*FYI - this post may contain affiliate links, which means we earn a commission at no extra cost to you if you purchase from them. Also, as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. Check out our Privacy Policy and Disclosure. for more info.

While three days in Rome may not sound like much, I can speak from personal experience that it’s plenty of time to eat spaghetti until you forgetti your regretti…

While doing some of that sightseeing stuff as well, I suppose.

I’ve explained before in my Rome travel tips post that you should dedicate at least four days to exploring Rome properly, but hey – I’m a big fan of challenges, and that’s how this three day Rome itinerary came to be.

Forged from the wisdom of three visits, I’ve designed this itinerary for spending three days in Rome with efficiency in mind, ensuring you see all of Rome’s top highlights, alongside some lesser known gems along the way.

So, if you’re spending three days in Rome in the near future, feel free to copy this itinerary, filled with fun facts, restaurant recommendations and a do-able plan of attack.

Save this 3 days in Rome itinerary for later!

You’ll be very glad you did.

Things to Book in Advance for Your Three Days in Rome

When in Rome….. get ready to plan ahead.

Honestly, one of my top Rome travel tips is to book everything in advance, from big attractions to popular restaurants. It’ll save you a ton of headaches (and often moola) in the long run.

If you are following my itinerary for three days in Rome, here are some bookings to make in advance:

- Colosseum Tour : I would advise booking for the early morning of your 2nd day, or a night tour like this one if you really want a unique experience without crowds

- Vatican Museum: If you wish to see it, book tickets for the Vatican Museum in late afternoon of the 3rd day, or splurge on a night-time tour like this one to avoid crowds

- Museum Tickets: I’d advise pre-booking tickets for any museums you want to visit (e.g. the Galleria Borghese ), although with only three days in Rome, I wouldn’t advise visiting too many museums as this can take up a lot of time

- A nice experience: I highly recommend booking a nice experience at some point like a street food tour , cooking class , or Vespa tour to make this trip truly unforgettable!

My Efficient Rome in 3 Days Itinerary at a Glance

Below, you’ll find my detailed 3 day Rome itinerary, where I’ll liberally blab about the context/history behind each attraction.

For your convenience and sanity however, here is a quick breakdown of each day:

Day 1 – Centro Storico, Jewish Ghetto and Trastavere

- Spanish Steps, Piazza di Spagna & Piazza Mignanelli

- Rinascente Roma Tritone (Optional)

Trevi Fountain

Galleria sciarra, chiesa di sant ignazio di loyola.

- Elephant and Obelisk

- Pantheon & Piazza della Rotonda

Piazza Navona

Chiesa di sant’ivo alla sapienza.

- Campo de’ Fiori & Passetto del Biscione (Optional)

- Largo di Torre Argentina

- Piazza Venezia & Il Vittoriano

Piazza del Campidoglio

- Teatro Marcello, Fontana delle Tartarughe (Turtle Fountain) & Tempio Maggiore (The Great Synagogue)

- Tiber Island

Day 2 – Ancient Rome & Aventine Hill

- Sunrise at the Roman Forum (Optional)

Colosseum Tour

- The Roman Forum & Palatine Hill

Circo Maximo (Circus Maximus)

Santa maria in cosmedin.

- Giardino degli Aranci

Day 3 – Vatican City, Castel Sant Angelo & Villa Borghese

- Vatican City

Castel St’Angelo

- Villa Borghese

- Terrazza del Pincio

Day 1 – Centro Storico, the Jewish Ghetto & Trastavere

We’re kicking off our three days in Rome with a whirlwind tour of the city’s most famous monuments in the Centro Storico, along with a visit to the Jewish Ghetto, and an evening in romantic Trastavere. The goal of Day 1 is to have you fall hopelessly in love with Rome…

So, get ready to rome-anticize your day.

The starting point of our Rome 3 Day Itinerary is the Spanish Steps , but before embarking on our epic journey of sightseeing, it’s important we address a vital need: coffee.

In Italy, coffee is most often slurped down at the bar for about a euro a piece, with a plain caffè (espresso) as the norm, although cappuccinos in the morning (usually about €1.30), paired with a cornetto, are a popular way to start the day.

In the vicinity of the Spanish Steps, you have a lot of fancy and historic options for coffee. Most coffee bars will give you a pretty consistently tasty and affordable coffee, but here are two unique options:

IMPORTANT: Make sure to have your coffee at the bar to avoid exorbitant sit-down prices.

- Antico Caffè Greco is the oldest coffee bar in Rome, dating back to 1760 with countless big names who have enjoyed coffee there over the years, from Goethe and Hans Christian Andersen to Princess Diana. Again, sit-down prices can be as much as 9 euros for a coffee, so make sure you order and drink yours at the bar.

- Atelier Canova Tadolin is a workshop turned restaurant/cafe that is packed with sculptures and plaster models, creating one of the most unique atmospheres for any caffeine hit in Rome… Just make sure you have your coffee at the bar, rather than sitting down.

Scalinata di Trinità dei Monti (Spanish Steps)

After you’ve hit your first of many espresso hits, it’s time to begin our three days in Rome with one of the most iconic sights of the city: the Spanish Steps!

These famous Baroque steps were designed by Francesco de Sanctis in the 1720s, who actually snagged the gig thanks to a competition held by a French diplomat turned financier, Étienne Gueffier.

The competition’s goal was to prettify the hilly terrain connecting Piazza di Spagna and Piazza Trinità dei Monti above, and props to Gueffier – I’m sure the thousands of tourists who photograph it daily would agree – mission accomplished!

PS: In case you’re wondering how many steps there are top to bottom, the answer is a steep 135, which means you’re definitely earning your gelato! That is, unless you decide to drive down like this drunk Colombian guy back in 2007 . Don’t worry though, no one was hurt!

Piazza di Spagna

Now, time to explore a bit more of the square – Piazza di Spagna , a square famous for a number of reasons (only one of which is the Spanish Steps!)

Firstly, famous English poet John Keats spent the final days of his life here, at 26 Piazza di Spagna which is today home to the Keats-Shelley House .

Standing in this square also puts you steps away from some of the top shopping streets in Rome, the most famous of which are Via dei Condotti (packed with luxurious brand names) and Via del Corso (packed with all the usual suspects of any High Street like Zara and the Disney Store).

As for the fountain at the foot of the steps, this often overlooked beauty is called Fontana della Barcaccia, AKA Fountain of the Boat.

It may be tough to see if there are (as usual) a bunch of tourists sat around it.

It depicts a half-sunken ship and was designed by none other than Pietro Bernini, father of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, whose works you’ll find all over the city.

Piazza Mignanelli

After capturing all your photos, it’s time to move onto the next stop: Piazza Mignanelli, home to the Column of the Immaculate Conception.

As you walk towards this column, you’ll pass by the Spanish embassy for the Vatican, said to be the oldest embassy in the world! Little wonder why it’s usually guarded at all hours by military in full camo.

The column itself dates back to Dec 8, 1857, exactly three years after Pope Pius IX published the Ineffabilis Deus , the decree which officially defined the dogma of the Immaulate Conception.

In other words, this was the decree that (after centuries of controversy) cemented the Catholic Church’s belief that the Virgin Mary conceived Jesus “free from all stain of original sin”.

… And that’s what this column (topped by a statue of the Virgin Mary herself) commemorates.

Every year on Dec 8 (the Feast of the Immaculate Consumption), they even host a ceremony here (usually attended by the Pope) during which local firefighters place a floral wreath on the statue’s right arm, a nod to the fact that it was firefighters who helped erect the statue all those years ago.

Optional Stop: Rinascente Roma Tritone

From Piazza Mignanelli to the Trevi Fountain, it’s only a 7 minute walk, but if you’re willing to make a short detour, then you can admire one of the lesser known ‘hidden gems’ in this tourist-heavy slice of Rome.

At Rome’s Rinacscente flagship location on Via del Tritone, you’ll find a department store where you can marvel at wonders from Gucci, Prada, Versace and…. perhaps most wonderfully, a piece of Acqua Virgo, a 2000 year viaduct that, at its peak, would provide up to 100,000 cubic metres of water to the city a day.

This part of the Acqua Virgo was only uncovered recently when restoration work began on the palazzo, and is part of the reason why the store was under construction for 11 years, delaying its opening date many times until it finally opened its doors in 2017.

Today, the “Acqua Vergine” viaduct (a successor to the ancient Acqua Virgo) continues to supply fresh water to Rome’s many fountains, including famous names like the Trevi Fountain… which is conveniently our next stop!

Next, let’s move onto the Trevi Fountain, perhaps one of the most famous fountains in the world and one of the most beautiful sights in Rome… especially after its gleaming new makeover in 2015 funded by fashion giant, Fendi!

Situated at the end of the famous Acqua Vergine Viaduct, its name comes from its location at the crossroads of three streets (tre vie). At 65 feet wide, this monumental fountain is best known for its impressive marble sculptures and of course its dreamy blue hues.

Today, millions of tourists come for a chance to ogle the fountain and partake in the classic tourist ritual of throwing a coin (or three) over their left shoulder… The 1st to ensure a return to Rome, the 2nd for romance, and the 3rd for marriage. So hey, maybe you should too. It’s cheesy, but “when in Rome”…

From the Trevi Fountain, it’s time to escape the crowds and take a quick 2 minute walk over to one of the prettiest hidden courtyards in Rome: Galleria Sciarra.

This unassuming walkway (tucked behind a McDonalds, no less) is a lovely hidden gem full of beautiful frescoes and artwork to admire, with a gorgeous glass and iron ceiling that makes the space feel impossibly grand.

… Especially when you consider that it’s simply home to offices these days!

Snap away, and let’s keep moving.

After you’ve had your fill of art nouveau eye candy, a 5 minute walk will take you from Galleria Sciarra to the Chiesa di Sant Ignazio di Loyola, a Jesuit church where another wonderful neck workout awaits.

This church is home to one of the most extravagant frescoes in Rome, and best of all – they’re free to admire and with a tiny sliver of the crowds that you might find at the Sistine Chapel.

These delightfully deceptive trompe l’oeil frescoes are the work of Andrea Pozzo, a master of Baroque (and a Jesuit brother) who painted the illusion in the late 17th century.

Want to make the most of the church’s unique optical illusions? Keep an eye out for marble disk markers on the floor that show you the best spots to stand.

Elephant and Obelisk

A 5 minute walk from the church will bring you to the smallest of Rome’s ancient obelisks, perched upon an elephant designed by Bernini.

Why the curious combo? Well, as a Latin inscription on the base of the pedestal notes “Let any beholder of the carved images of the wisdom of Egypt on the obelisk carried by the elephant, the strongest of beasts, realize that it takes a robust mind to carry solid wisdom”.

So yes, all in all, the monument is an homage to wisdom.

Pantheon

Now, onwards to Rome’s iconic Pantheon, which is only a 2 minute walk away.

Of all the buildings that remain from Ancient Rome, the Pantheon is by far the best-preserved, dazzling visitors even 2000 years after it was originally constructed.

And there’s a lot of reasons to visit – after all, the Pantheon houses tombs for some of Rome’s most famous figures, including Italy’s 1st King, King Vittorio Emanuele II and Ninja Turtle namesake, the famous painter Raphael.

The Pantheon’s dome is also the largest unsupported concrete dome in the world.

At the apex of this dome is the 27 feet wide oculus, which floods a bright ray of light into the Pantheon… and rain when the weather feels moody. That’s why you’ll find 22 manholes on the Pantheon’s floor – to filter said rain when it pours.

Piazza della Rotonda

Once you’ve had your fill of the Pantheon’s epicness (truly, visiting is one of my favourite things to do in Rome!), step outside and let’s admire this bad boy’s exterior from Piazza della Rotonda, so-named for the Pantheon’s lesser known title as the church of “ Santa Maria Rotonda ”.

While standing in front of this impressive 2000 year old tourist magnet, take note of the 16 giant granite columns that hold up Rome’s swankiest front porch.

Believe it or not, these columns were actually brought here all the way from Eastern Egypt – a pretty remarkable feat considering their epic size.

As for the inscription on the front facade of the building, that reads “M. Agrippa L. F. Cos. Tertium fecit”, which translates to “It was built by Marco Agrippa, son of Lucio, in the year of his third consulate”.

This is a nod to the original Pantheon’s designer, Marco Agrippa. Today’s version is actually the Pantheon’s 3rd iteration though, after the first two were destroyed by fire and lightning.

Lunch: Armando al Pantheon

While dining near tourist attractions is usually a rookie mistake in Rome, a notable exception is Armando al Pantheon, which serves excellent food at fair prices, literally steps away from the Pantheon.

I can highly recommend the Spaghetti Carbonara, which was top notch. My friends also spoke highly of their Cacio e Pepe.

Coffee: La Casa Del Caffè Tazza D’oro

If you need a little pick me up after lunch, La Casa Del Caffè Tazza D’oro is just around the corner and has super delicious coffee for a very fair price.

Slurp it up at the bar standing up (the sit-down prices are much higher), and let’s keep moving!

From the Pantheon, it’s only a 5 minute walk to Piazza Navona, one of the grandest Baroque squares in Rome.

The first impression for most visitors here is the oblong shape of the piazza, which stretches lengthways far more than a conventional square.

Well, that can be explained by Piazza Navona’s history.

It stands over top the ancient Domitian Stadium, which was built back in the 1st century to introduce Greek-style athletics and (non-violent) sports to the Roman public, whose main source of entertainment was pretty much watching slaves murder each other with cameos from lions, tigers, and bears.

Unfortunately, Romans far preferred their bloody gladiator games, and over the centuries, the stadium fell into disuse, eventually being pillaged for building materials.

It wasn’t until the 17th century that (under the command of Pope Innocent X), the space was transformed into a gorgeous Baroque piazza, complete with works from big names like Bernini and Borromini.

Today their masterpieces can still be admired in the square, most notably the Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi ( Fountain of the Four Rivers) by Bernini and the Sant’Agnese in Agone which was designed by Borromini alongside father and son duo Girolamo Rainaldi and Carlo Rainaldi.

For more Baroque splendour, you can walk two minutes over to the Chiesa di Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, which sits in a beautiful courtyard now belonging to Rome’s State Archives.

This is a great place to escape from the crowds a bit, and learn more about the pettier side of Rome’s Baroque turf wars. According to popular legend, the church was originally meant to be Bernini’s project, but it was handed over to Borromini when Pope Urban VIII died.

It is said that Borromini sculpted some donkey ears on the construction site to taunt Bernini (who he saw as a bitter rival), and Bernini (who lived next door) sculpted a phallus right back.

Optional Stop: Campo de’ Fiori

Translated literally to “Field of Flowers”, the Campo de’ Fiori is a square found south of Piazza Navona, so-named for the lush meadow that was once found there.

By day, it’s home to a busy market selling produce and flowers. By night, it’s a gathering spot with terraces filled with people eating, drinking, and making merry. In my opinion, it’s not the most beautiful piazza in Rome, but it’s worth checking out during the day if you’re curious to see a Roman market in action.

Most interesting to note here is the statue of Giordano Bruno in the center, which serves as a reminder of the square’s dark past.

Once used for public executions, the Campo de’ Fiori is where Bruno (a philosopher, astronomer, and mathematician) was hung and then burned at the stake for his so-called “heretic” beliefs that ran contrary to the Church.

… But yes, today you can honour his memory by buying vegetables and jam where he was brutally burned to death. Isn’t tourism fun?

Passetto del Biscione

BONUS TIP: From Campo de’ Fiori, walk through the Passetto del Biscione for a fun hidden treasure – a narrow tunnel-esque valley adorned with frescoes.

Here, you’ll find (a copy) of a famous Madonna painting that sent the people of Rome into a spiral of hysteria back in 1796, when it was reported that the painting’s eyes were moving… a miracle that drew countless worshippers to visit for themselves.

Funnily enough, the hidden nature of the passage made the task quite difficult, which inspired the popular Roman saying “ andare a cercare Maria per Roma”, which translates to “looking for Mary in Rome”, a phrase now used to describe the difficulty of finding something.

Largo di Torre Argentina

From the Campo de’ Fiori, you’re about a 6 minute walk from some of the most interesting ruins in Rome, set among an ensemble of modern shops, cafes, and restaurants.

Discovered in the 1920s during city building works, the Largo di Torre Argentina includes ruins from four ancient temples (likely built to commemorate victories), the ancient Theatre of Pompey and, most significantly, the Curia of Pompey, which is where Julius Caesar was famously stabbed to death by traitors in his Senate back in 44 BC.

Of course, despite this (huge) historical significance, the ruins are perhaps best known these days for being home a thriving cat sanctuary, so don’t be surprised if you spot a furry friend or two frolicking around the ancient site.

Piazza Venezia

It’s less than a 10 minute walk from Largo di Torre Argentina to Piazza Venezia, an overwhelmingly large and chaotic square that connects the Centro Storico with some of the best preserved monuments of Ancient Rome.

On the West side of the Square, you’ll find Palazzo Venezia, which has served multiple functions over the years, from its status as a papal residence in the 15th century, a Venetian embassy in the 16th century, and Mussolini’s office in the 20th century.

In fact, it was on the small balcony still seen today on the palazzo’s front facade that Mussolini declared war on France and Britain in 1940.

Today, the building houses the National Museum of Palazzo Venezia.

Il Vittoriano

The focal point of the square however is no doubt the gleaming Neoclassical monument in the center that goes by many names, from the Vittoriano and the Altar of the Fatherland (which refers to the central altar of the monument), or much more whimsically, the “Wedding Cake” or “Typewriter”.

This pristine marble monument was constructed in the late 19th century to commemorate Vittorio Emanuele II, the 1st king of a unified Italy. It was officially inaugurated in 1911, 40 years after unification.

Since 1921, the monument has also housed the “Tomb of the Unknown Soldier”, a shrine dedicated to those who perished and sacrificed their lives during World War I. The tomb is guarded by two eternal flames and two soldiers, who stand there at all hours of the day.

While it’s controversial, this mammoth structure is (to me) a must-see in Rome because It’s completely free to visit, with only an additional fee for the elevator ride up the terrace if you so choose. I’d highly recommend checking it out!

Our next stop is Piazza del Campidoglio, the last remaining Renaissance Square in Rome, designed by Michelangelo.

You know the phrase “all roads lead to Rome”? It’s this part of Rome that they were specifically talking about.

Once upon a time, this square is where the roads on Ancient Rome converged, although it looked very, very different back then. It wasn’t until the 16th century that makeover plans began.

Panicked by an impending visit from Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Pope Paul III recruited the help of Michelangelo to beautify the square and (fingers crossed) impress the emperor.

And while the square wasn’t fully completed until a full century after Michelangelo’s death, the efforts paid off, and today Piazza del Campidoglio is truly one of the most beautiful squares in the entire city, lined with elegant palazzos that house important institutions like the Capitoline Museums and Rome’s City Hall.

SCENIC DETOUR: If you follow Via del Campidoglio downhill for a bit from the Piazza del Campidoglio, you reach one of the most beautiful viewpoints in Rome, a glorious vista overlooking the Ancient Roman Forum! Don’t worry – if you follow this 3 days in Rome itinerary, we’ll be visiting this site tomorrow.

Teatro Marcello

From Piazza del Campidoglio, it’s less than 10 minutes on foot to the Teatro Marcello, a Colosseum mini-me that once served as an open air theatre for musical and dramatic performances.

While it’s only possible to admire it from the outside, it’s nonetheless an interesting monument that predates even the famous Colosseum, and one that was commissioned by Julius Caesar himself.

The Teatro Marcello is sometimes referred to as the Jewish Colosseum, thanks to its location in Rome’s Jewish Ghetto, so-named for its centuries-long stint as a walled neighbourhood in which Roman Jews were forced to live, often in appalling conditions.

It may be difficult to imagine today, given that the Jewish Ghetto is one of the most picturesque neighbourhoods in Rome, but lurking beneath those pastel facades and cobblestone streets is a sad and sinister history, ranging from the establishment of the Ghetto in 1555 all the way to the Nazi occupation of Rome, when over 1000 Jewish residents of the Ghetto were detained by the Gestapo and sent to Auschwitz Concentration Camp.

Today, the Jewish Ghetto is one of the quieter and more peaceful parts of Rome’s city center in terms of tourism, but those who visit are treated to a number of popular bakeries, restaurants, and interesting sights like The Great Synagogue (home to the Jewish Museum of Rome).

If you have some extra time in Rome, exploring the Jewish Ghetto is a great way to get a bit more off the beaten path.

Fontana delle Tartarughe (Turtle Fountain)

A short walk around the neighbourhood will bring you over to the Fontana delle Tartarughe (Turtle Fountain), a pretty Renaissance fountain in Piazza Mattei originally designed by Giacomo della Porta, perhaps made all the more famous by small bronze turtles attributed to Bernini.

The fountain depicts four young adolescent men (known as Ephebes), perched over giant conch shells. The original design had the Ephebes holding up dolphins who spouted water, however water flow issues meant that these needed to be removed.

It wasn’t until a restoration many years later that they decided to fill the empty space left by the removed dolphins with cute little turtles, which give the fountain its name today… although the turtles you see now are copies of the original (which are now safely kept in the Capitoline Museums),

Tempio Maggiore (The Great Synagogue)

Before we leave the Jewish Ghetto, we have a final stop – the Tempio Maggiore, known in English as the Great Synagogue of Rome.

It’s a little known fact that the Jewish community in Rome is actually considered the oldest in Europe, with stories of settlement dating back to 160 BC.

And despite the Ghetto’s dark history, the Great Synagogue stands today as a symbol of the resilient Jewish community that continues to call this neighbourhood home.

Inaugurated in 1904, this synagogue is the largest of the 13 synagogues in Rome, with a striking eclectic design topped with a unique square-shaped dome.

Today, the synagogue complex is also home to the Jewish Museum of Rome.

Cross Ponte Fabricio onto Tiber Island

Now, it’s time to visit the only river island in Rome… and we have a very historical route for getting there.

Two minutes away from the Great Synagogue, you’ll find the Ponte Fabricio – the oldest bridge in Rome that still stands in its original form, which dates back to 62BC!

From the Jewish Ghetto, we can cross this bridge to access Tiber Island, a suitably epic way to enter the birthplace of some of Rome’s proudest citizens (more on this below).

Isola Tiberina (Tiber Island)

Crossing the bridge will bring you over to the Isola Tiberina (Tiber Island), a legendary bite-sized island that has been connected to the Roman ‘mainland’ since the Ancient Times.

Due to its tiny size (less than 300m long and 70m wide), it is considered one of the smallest inhabited islands in the world, home today to a hospital and two churches.

In fact, it is said that those born at the Fatebenefratelli Hospital on Tiber Island use it as a point of pride – claiming that they are true Romans for having been born there.

Much legend and mystery swirls around the island’s millenia-long history, but one consistent theme is that the island has always been a place of of refuge and healing, a legacy that began in the 3rd century BC when a temple to Aesculapius, the Greek god of healing, was constructed.

This spirit of refuge is embodied by my personal favourite story about the island, dating back to 1943, when doctors at Fatebenfratelli Hospital diagnosed Jewish refugees with a fabricated illness known as “Syndrome K” to prevent their deportation.

Today, Tiber Island is a quiet escape from the chaos of the Eternal City, that is unless you visit during the summer, when they host a full program of outdoor movies.

Evening: Trastavere

Crossing the Ponte Cestio, you will arrive at one of my favourite neighbourhoods in Rome – Trastavere, famed for its abundance of restaurants, cafés and beautiful medieval streets, all tied up in a mega-photogenic package.

While some might have considered Trastavere a local secret years ago, such is no longer the case, and the tasty charms of the neighbourhood are now irresistible to both tourists and locals like.

Nonetheless, it’s a must-visit when in Rome to see a different side of the city, relaxed and vibrant, away from the historical center.

This is the ideal place to wrap up a day of sightseeing, because you’ll find no shortage of restaurants and bars here to keep you busy.

Exploring Trastavere without a plan is the way to go. Every street here seems to be filled with flower-entwined balconies, tall golden buildings trailing with ivy, and twinkly lights to create the most romantic possible ambiance.

Unlike the Centro Storico, Trastavere is not a neighborhood filled with must-see landmarks (although the Basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere is quite pretty) – instead, it’s a place to meander without agenda, grab an aperitivo, and unwind a bit after some relentless sightseeing.

Dinner: La Tavernetta 29 da Tony e Andrea

For a tasty, affordable and fun dinner in Trastavere, I can definitely recommend La Tavernetta 29 da Tony e Andrea. The servers here are hilarious, and the whole place has a chaotic ‘crazy family dinner’ sort of energy that completely made our evening.

Of course, the food here was awesome too. I can definitely vouch for the Cacio e Pepe, but the Fried Zucchini Blossoms were also really good.

Otherwise, there’s no shortage of great restaurants in Trastavere. If you’re looking for a to-go option, Trappizzino is a classic street food option that originated in Rome, but now has locations across Italy and even one in New York.

Drinks: VinAllegro

If you’re still not ready to leave Trastavere after dinner, I can recommend checking out VinAllegro, a really cute wine bar that’s covered in ivy.

It’s a little off the main drags of Trastavere so it has a quieter and more romantic atmosphere, plus the drinks are very affordable. I’ve heard the food is nice too, but it’s a great stop even if you’re just having a glass of wine… which would be much deserved after this whirlwind 1st day on our three day Rome itinerary!

Day two of our three day Rome itinerary will tackle some of the most famous sights of Ancient Rome, along with some glorious, unforgettable viewpoints. Make sure our cameras are properly juiced up for this day, because you’ll likely capture entire SD cards’ worth of photos.

Optional: Sunrise at the Roman Forum

I know this sounds like a LOT, but if you’re feeling especially motivated, then I’ve heard seeing sunrise by the Roman Forum is absolutely magical.

As I mention in my Rome travel tips post, particularly in peak season, the best way to avoid crowds and feel like the city is all yours is to get up early… and nothing beats sunrise early, if you can handle it after all those vinos last night in Trastavere.

The best vantage point would definitely be from Via del Campidoglio (downhill for a bit from the Piazza del Campidoglio), a photographer favourite for sunrise shots in Rome.

If you value sleep over snapshots, then there’s zero shame in getting up at a more reasonable hour.

Today’s itinerary is heavy on sights and history, so you’ll need plenty of coffee for this one. I’d recommend pillaging any local coffee bar near your hotel to prepare for the busy day ahead.

NOTE: This requires advanced booking for sure. Try to book the first time slot available (usually 9:30am) or any time before noon to minimize heat in peak season – it can get horrifyingly hot.

Anyways – it’s the most famous monument in Rome, and an enduring symbol of Italy as a whole, so it makes sense to start Day 2 of our three days in Rome at the Colosseum, also known as the Flavian Amphitheatre.

This incredible structure dates back almost 2000 years, and remains the largest standing amphitheatre in the world.

For centuries, it was here that Rome’s infamous gladiator fights and animal hunts took place, often to crowds as large as 80,000. Today, it can receive up to 30,000 visitors a day, making it one of the most visited monuments in the entire world.

And, thanks to a recent development, the Colosseum’s Underground area is open to visitors in full for the first time in its almost 2000 year history, making a visit to the inside an absolute must-do.

A SPLURGEY OPTION : If you don’t mind paying extra for a truly unique experience, you can also book a tour to visit the Colosseum at night when you’ll have it pretty much all to yourself. Click here to check out prices and reviews.

PRO TIP: It can be difficult to get a good photo of the Colosseum due to its ginormous size, but the perfect vantage point for a shot or two is Via Nicola Salvi, where a perfectly photogenic perch awaits

I’d really recommend grabbing lunch before powering through to the Forum, because that’s a lot of sightseeing to do all at once.

If however you want to avoid the worst of the heat, then doing the Forum first might be a good idea.

Regardless, since today is super full-on with sightseeing, I’d recommend a quicker lunch to maximize your time. I can wholeheartedly recommend Pane & Vino on Via Ostilia , which has tons of super tasty sandwiches (the Porchetta is amazing!) for fair prices considering their location.

For a sit-down lunch, I’ve had good experiences twice at Trattoria Luzzi (the prices are a very fair for the area and the food really good!), but I haven’t been there in a few years and more recent reviews are less promising.

The Forum & Palatine Hill

Alright, let’s power through now to The Roman Forum.

It may be hard to imagine, but this giant expanse of ruins was once the epicenter of commercial and government activity in Ancient Rome.

This multi-purpose space would have been used for countless aspects of daily life, from elections and social gatherings to religious ceremonies and criminal trials.

In other words, you are staring directly at the heart of Ancient Rome… or what remains of it, anyway.

To be honest, I find the Forum and Palatine Hill a little bit difficult to enjoy without a guide (or a guidebook) mainly because you don’t have any context as to what you are looking at.

I would highly recommend booking a tour guide for this portion of your three days in Rome itinerary, or at the very least find a free guide online that will teach you more about the sites’ history.

While in the Forum, you can walk right up to Palatine Hill, which yields wonderful views. Many consider this hill to be the birthplace of Rome, since according to Roman legend, it was here that the city’s founders Remus & Romulus were found & saved by a she-wolf (it’s a long story).

For centuries, Palatine Hill was one of the swankiest neighbourhoods in Rome, beloved by emperors and the city’s elite. Sadly, the few ruins that remain make it hard to imagine how glamorous it would have all looked in its hey day, but the views are fantastic.

Exploring the monuments of Ancient Rome is a LOT, and (particularly when the weather is hot), it can take a lot out of you.

Before we soldier on to our next stop, I’d recommend stopping somewhere for a refreshing gelato or drink. You deserve a treat after filling your brain with all that history!

When you’re ready, let’s head to our next stop: the Circus Maximus, one of the world’s first large-scale sporting arenas.

This is where Rome’s famous chariot races would have taken place back in the day, along with plays, gladiator fights, and other athletic displays.

It may be hard to imagine now, but back in its hey day, the Circus would have been able to host over 150,000 spectators. Today, only a few ruins here and there allow you to imagine its grand past, although a new VR experience at the site is hoping to help!

Because so little remains of the Circus, I wouldn’t necessarily class this as a must see in Rome, but it’s a nice stop en route to some beautiful viewpoints, as you’ll soon see.

Moving onto our next stop – let’s go see the Basilica di Santa Maria in Cosmedin.

This is an 8th century church that is home to a legendary lie detector, Rome’s tallest medieval belfry, and the literal heart of Saint Valentine.

The Bocca della Verità (Mouth of Truth) is a famous marble mask that (according to legend) bites off the hands of liars. It first made its way into popular culture through an appearance in Roman Holiday, and has been a check off every tourist’s bucket list ever since.

Sure it’s little more than a cheesy photo opp, but it’s a fun one, especially if you want to watch your travel partners sweat a little… before promptly bringing them over to see the flower crowned skull said to belong to St Valentine himself.

Il Buco della Serratura dell’Ordine di Malta (AKA the Roman Keyhole)

Nearby, you’ll also find another of Rome’s most beloved photo opps – Il Buco della Serratura dell’Ordine di Malta , known more popularly as Rome’s Keyhole.

This famous keyhole can be found at the entrance of the Villa del Priorato di Malta (the Villa of the Priory of the Knights of Malta).

Its claim to fame is the unique view of St Peter’s Basilica that you can access through the keyhole, which is perfectly framed by hedges to create a surreal and dreamy postcard view.

While waiting in line to look through a keyhole does indeed make you feel like an irreprehensibly cheesy tourist, the perspective is indeed very cool, and well worth a quick peek…

Sunset: Giardino degli Aranci

Ahh, with all that sightseeing done, now it’s time to relax and enjoy some amazing views.

The Giardino degli Aranci , also known by its official name, Parco Savello, is a leafy garden on Aventine Hill that is lined with its namesake orange trees, offering some much-needed relief from the sun in peak season.

The garden’s current design by Raffaele De Vico dates back to only 1932, when the scenic viewpoint/terrace was installed to give visitors a better view over the city.

And what a view it is!

This is definitely one of the prettiest panoramic vantage points you can enjoy in the city, with an ultra-romantic atmosphere too. This is a great place to watch sunset before enjoying some well-deserved dinner.

From Giardino degli Aranci, you’re close to both Trastavere and Testaccio, two neighbourhoods filled with a wonderful choice of restaurants.

If you’ve followed this three days in Rome itinerary closely, you’ll have already enjoyed the wonders of Trastavere last night, so consider spending your evening in Testaccio, known as Rome’s ultimate foodie neighbourhood.

Overwhelmed by the choices? I recommend reading some local Roman food blogs like Testaccina for stellar food recommendations.

Day 3 – Vatican City & Castel Sant Angelo

For the final day in our three day Rome itinerary, we are visiting the Vatican, Castel Sant Angelo, Piazza del Popolo and Villa Borghese. Nope, no rest for the wicked. Let’s get moving!

NOTE: Make sure to check the Vatican website to ensure that your visit won’t overlap with a Papal Audience, unless you are wanting to attend one. Otherwise, this will mean huge crowds which is not ideal.

Breakfast: Osteria Café del Monti

Vatican City is not only the smallest country in the world, it’s also one of the most popular sights in Rome, which means tourists and tourist traps galore.

Of course, to conquer this, we need coffee… and to wake up early!

There are a lot of bad cafés and restaurants near the Vatican, so give them a miss and head to Osteria Café del Monti , which has fair bar prices and really tasty pastries.

Consumed at the bar, our cappuccinos and pastries were only 1.50 each, a total bargain for its central location near the Vatican (where you’ll find many foot spots swarming with negative reviews of high prices and scams).

Again, remember that you will be charged double for sit-down service, so treat this as a quick breakfast stop, slurp your coffee at the bar and get back to sightseeing.

Visit St Peter’s and Climb Up the Dome

Arriving early to St Peter’s is key to avoiding the huge crowds that arrive here en masse no matter the season.

After all, this is the largest church in the world, and among the most beautiful. In fact, we can almost look at St Peter’s as a collaborative effort spanning over a century from some of the most famous names in art, from the original architect Donato Bramante to Raphael, Michelangelo and Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Today, stepping into St Peter’s Basilica is a truly breathtaking experience, with its monumental interiors made of marble, bronze, and gilding as far as the eye can see.

In fact, turn immediately right and you’ll see Michelangelo’s Pietà, considered one of the most spectacular sculptures ever carved… although tucked behind bulletproof glass now, after a crazed Hungarian geologist hammered at it back in 1972 .

Of course, the dome of the Basilica is also considered to be the largest dome of its kind in the world, so if you have the time and stamina, I highly recommend the climb (or the elevator ride + climb if you prefer). It’s not possible to book this in advance, so you can just make your choice the day-of.

As I mention in my Rome travel tips post, the ideal way to visit St Peter’s is the following:

- Enter the cathedral, have a quick look around to get a feel of the grandeur of it

- Head down to the papal tombs, and the exit will take you back outside, conveniently where the ticket office is for the climb up the basilica dome

- Climb up the tower (time your visit for the hour mark to hear the bells ringing across Rome!), enjoy the views from above

- Climb back down (the exit will actually bring you back into St Peter’s) and finish your explorations

Send a postcard from the Vatican Post Office

After experiencing the grandeur of St Peter’s Basilica, it’s time to head back out to St Peter’s Square.

If you want to, the Vatican Post Office is strategically placed right by the exit, giving you the unique opportunity of buying/sending a postcard from the world’s smallest country.

Is it a little cheesy? Maybe… it’s definitely a cheap and memorable souvenir.

TIP: Bring a pen for your visit – they charge 1.50 for their cheapest pens (no joke!) and sometimes they even sell out.

Explore some of the interesting secrets of St Peter’s Square

If you haven’t had your fill of Vatican City yet, I’d like to point you towards some often overlooked parts of St Peter’s Square that are worth checking out.

First off, if you head close to the right side screen in the square, you may see a plain marble plaque embedded in the dark cobblestones.

This plaque is engraved with the coat of arms of Pope John Paul II, who survived an assassination attempt on this very spot back in 1981.

And from interesting assassination monuments to interesting architecture, make sure you check out the most unique perspective of the colonnades that St Peter’s Square has to offer.

These two colonnades run 4 columns deep, and were expertly designed by Bernini himself to resemble welcoming arms outstretched for an embrace. But while countless visitors pass through the colonnades every day, many fail to appreciate the coolest vantage point of these columns.

So, don’t make that mistake! When in St Peter’s Square, look for the two iron circles on the ground (halfway between the central Obelisk and the fountain on each side) and look forward.

Those columns that run 4 rows deep will now align perfectly, creating the illusion that there’s only a single row of columns. Pretty wild!

Lunch: Bonci Pizzarium

Okay, after all that sightseeing, you deserve a good feed.

Pizza is an Italian superfood beloved the world over, but if you want to try a Roman style pizza, then Bonci Pizzarium is a great place to visit for Pizza al Taglio, a Roman style of pizza that is served in rectangular slices and sold by weight.

The pizzas here are beautiful and the toppings are unique, plus the entire experience is a little different since you pay by weight and indicate how big you want your slice to be before watching them snip away at it with scissors.

The downsides though are…

- The pizza is more expensive than you’d find elsewhere in the city

- The toppings can be pretty creative, so you might chance upon one you don’t like

- There can be long line-ups and crowds

- There’s nowhere to actually eat the pizza on-site (no tables)

So, if you’re looking for more of a laid back and relaxing lunch, then I have another recommendation – Borgo 36, only a 5 minute walk from St Peter’s Square. The food here is unpretentious, fairly priced, and delicious!

Optional: Vatican Museums

After lunch, you might consider visiting the Vatican Museums. I personally would mark this as a very optional visit, and here’s why.

I may get some flack for this, but I don’t think the Vatican Museums are necessarily a must-do when you’re visiting Rome, especially if you’re trying to make the most of Rome in 3 days.

I get it: it feels like one of those things you MUST do because everyone says it is (akin to the Louvre in Paris ), but I’ve visited twice and am still pretty lukewarm about it, because…

Firstly, it can be SO crowded with large tour groups that you can barely move. Yes the architecture and artwork are fantastic, but the crowds can really take away from the experience.

Secondly, the Sistine Chapel (arguably the museum’s most famous attraction) is very dimly lit, and the atmosphere is incredibly bizarre.

Not only is it crowded in there, guards inside demand utter silence yet ironically have to “SHUSH” tourists super loudly every 5 seconds. Photography is also prohibited, although everybody and their mom’s cousin will still try to sneak a blurry photo.

All in all, yes the frescoes are magnificent, but if you’ve seen them before thanks to infinite references in pop culture, seeing them in real life doesn’t really blow you away.

That’s my personal experience anyway.

If you do still want to visit though, here are some tips I can offer:

- Time your visit for the last entry time. Going before it closes is usually less crowded than the mornings as most tours have left by then

- Book a private after hours tour. This is a VERY pricey option but well worth it if you want the ultimate Vatican Museum experience – this tour takes place only once a week (so you must prebook) but allows you to experience the Vatican Museum and Sistine Chapel with literally no other tourists.

- Book this early morning tour, which gives you entry to the Sistine Chapel before it opens. The downside is you’ll be touring the museums once it’s open to the public, so you won’t be protected from those crowds, but if the Sistine Chapel is your #1 priority, this could be a good middle ground option.

Alright, it’s time to say goodbye to the Vatican and move on to our next stop: Castel St’Angelo.

NOTE : If you can time your visit with sunset (easier in winter months), then absolutely do. The views at this time are spectacular.

The Castel Sant’Angelo is a really special Roman attraction because of its colourful history. Few monuments in Rome have evolved with the city’s history and power struggles as much as this one, which has been around since the 2nd century.

Originally built as a mausoleum for Emperor Hadrian, it was later converted into a castle by the Popes, who from the 14th century onwards began to add their own little flourishes like chapels and statues to glam up the place to their liking.

Luckily they got a lot of use out of it – not only has Castel Sant’Angelo been a fortress and safe haven, it has also been used as a prison, and more recently, even a film set, where it starred as a key location in Angels & Demons and Eat, Pray, Love.

There aren’t many attractions in Rome that quite capture the city’s evolution from the Ancient Roman Empire to its present day pop culture stardom, so this Castel is definitely worth a visit.

Piazza del Popolo

Our next stop is a 20ish minute walk from Castel Sant’Angelo to Piazza del Popolo, or (much quicker) a quick 7 minute taxi ride.

TIP: If you are ever getting a taxi in Rome, I recommend ordering one through an app like FREE NOW to avoid getting scammed.

Translated as “The People’s Square”, Piazza del Popolo is considered one of Rome’s most important (and aesthetically pleasing) squares, housing a number of attractions including the Leonardo da Vinci Museum, the twin churches of Santa Maria in Montesanto and Santa Maria dei Miracoli, and the Basilica di Santa Maria del Popolo.

Where you’re standing now is actually the far northern end of the Aurelian Walls, ancient defensive walls from the 3rd century that still (to this day) serve an important purpose – they use them as a marker for deciding taxi fares from the airport, with any destination within the walls qualifying for a single flat rate.

In fact, the Porta del Popolo (the monumental gate at this end of the walls) served for centuries as a popular entry point for visitors. They also used to love this square for public executions, but that’s another story for another time.

Enjoy Villa Borghese

From Piazza del Popolo, a short walk up some stairs will bring you to Villa Borghese, one of Rome’s prettiest and largest public parks, home to a number of villas and museums, including the Galleria Borghese, one of Rome’s most famous art galleries.

Since we’re nearing the end of our three days in Rome, I wanted to leave this last stop as fairly open-ended and relaxing.

There is a lot to do in Villa Borghese – I can recommend renting a rowboat at the little lake by the Temple of Asclepius – it’s 4 euros per person for twenty minutes (which is more than enough to enjoy a quick paddle around the lake as it’s really small).

This is a really lovely and cheap activity that you’ll remember for years to come.

Alternatively, if you’re big into museums, you can visit the Galleria Borghese.

As one of the more famous attractions in the city, I can recommend visiting just before their last admission time – this way it’s less likely to be heaving with crowds as most groups will have left by then, although they do control the number of visitors here so that shouldn’t be too much of an issue.

OPTIONAL: From the Galleria Borghese, it’s only 15 min on foot to one of the most unique neighbourhoods in Rome – Quartiere Coppedè, which is peppered with spectacular art nouveau buildings that create a sort of fantasy dreamscape unlike anywhere else in Rome.

Sunset at Terrazza del Pincio/Belvedere Terrace

Alright, now are you ready for a true showstopper?

To cap off this jam-packed Rome in 3 days itinerary, let’s finish off with a sunset at the Terrazza del Pincio, widely regarded as one of the most amazing places in Rome to enjoy sunset… all the better if you bring yourself a bottle of wine!

If you aren’t completely exhausted, I think booking a night tour of Rome (whether by E-Bike like this one or Golf Cart like this one ) would be a wonderful way to finish off the trip, especially since you might have missed seeing many of these monuments at night.

Otherwise, head straight to dinner, and treat yourself a little for your final night in Rome!

Or, maybe get the best of both worlds and enjoy a final cooking class like this one where you make your own dinner (and take home some treasured secrets of Roman pasta and tiramisu)… no matter how you choose to celebrate your final evening in Rome, make sure it’s special!

Extra Tips if You Have More Than 3 Days in Rome

The 3 day itinerary for Rome I created above covers most of your bases in terms of the must sees, but if you have additional time to play with, here are some recommendations.

Book a unique experience

Sightseeing non-stop is a great way to enjoy your three days in Rome, but what would make it even better (for those with additional time) is booking an unforgettable experience.

I promise this is the perfect way to round out your trip, whether you’re simply having a nice splurgey dinner, or doing something more hands-on like a cooking class.

Here are some additional ideas for your Rome itinerary:

- A Vespa tour like this one

- A street food tour like this one

- A pasta and tiramisu making class like this one

Explore some of the cool gems around Termini Station

Rome is such a historic city that the 3 day itinerary above barely scrapes the surface in terms of all the cool sights you can find.

Particularly around the Rome Termini Station, you’ll actually find a few interesting sights that are bit more off the typical tourist path, like:

- Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri: A church designed by Michaelangelo in old bath house ruins with a cool Meridian Line

- Fontana dell’Acqua Felice: A unique fountain with a giant Moses statue

- Chiesa di Santa Maria della Vittoria: Home to the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, possibly the most famous of Bernini’s sculptures

- Quattro Fontane: An intersection with four late Rennaissance fountains perched elegantly on each corner

- Basilica di San Pietro in Vincoli: A church home to the chains said to have held St Peter prisoner in Jerusalem, and Michelangelo’s famous Moses statue

Take a day trip to Tivoli

If you have additional days in Rome, I can highly recommend a day trip to Tivoli, which is only 33km away. The gardens at Villa d’Este are truly some of the most beautiful gardens I’ve seen in my entire life.

If you don’t have a car, this is a day trip I recommend doing with a guided tour, because getting between villas is a bit cumbersome with public transport. Here is an affordable option that includes lunch.

Take a day trip to Pompeii

While this is a much lengthier day trip, it’s a must-do for history lovers. After all, how often do you get to ‘time travel’ back to the year 79AD?

This is another experience I recommend booking with a tour guide, because context is SO important with Pompeii.

Here is an option from Rome with 1000+ positive reviews.

Explore some of Rome’s other less famous neighbourhoods

Lastly, while Rome is a great city for tourists, I’ve been told by local birdies that it’s also a wonderful place to live.

So, if you have more than three days in Rome, make sure you pencil in some time to discover the more local side of Rome by exploring neighbourhoods beyond the touristy classics like the Centro Storico and Trastavere.

I’ve heard wonderful things about Testaccio in particular, if you love food as much as I do.

I hope this Rome in 3 Days Itinerary was Helpful!

Let me know in the comments if you have any more questions, or suggestions for my next trip.

My Go-To Travel Favourites:

🧳 Eagle Creek: My favourite packing cubes

💳 Wise: For FREE travel friendly credit cards

🍯 Airalo: My go-to eSIM

🏨 Booking.com: For searching hotels

📷 Sony A7IV: My (amazing) camera

✈️ Google Flights : For finding flight deals

🌎 WorldNomads: For travel insurance

🎉 GetYourGuide: For booking activities

1 thought on “A Magical 3 Days in Rome Itinerary”

This 3 day itinerary looks like a week of sightseeing, taking notes already of all the places I can go. Thank you.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

By using this form you agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website. *

Closed today

Our opening hours are:

Monday – Friday

Call us: 01737 218 807

Search Discover the World Education

20th century history trip to rome italy.

4 Days from £540pp

Based on 40 students travelling with 4 teachers (free places)

All around the vibrant city of Rome, there is still evidence of its turbulent past with the effects of the rise and fall of Mussolini and the Fascist party imprinted on the city.

History students can develop their understanding of remarkable eras throughout Italy’s history with stops at Colosseo Quadrato, Circeo National Park, the Museum of the Liberation of Rome, and much more. As you explore Rome, you will visit key locations lifted straight from the pages of your textbooks to bring learning to life.

Below is an example itinerary showing what your visit to Rome could include. We also provide a fully bespoke service, and our internal Travel Specialists will help you design the perfect trip unique to your school.

What's included

- Return flights to Rome from Gatwick

- Hold luggage for all passengers

- 3 nights' accommodation

- Half board basis (breakfast and evening meals)

- Guide and/or tour assistant where specified

- All activities mentioned in the itinerary

- Our Covid Money-Back Assurance

Ask about our approach to Responsible Travel

We believe the benefits of travel should not be lost for the next generation. In order to protect this world we live in and also inspire a new group of young people to fight for our planet, we are developing an approach to Responsible Travel that is founded in facts, empowers young people to take action and involves suppliers at all levels in minimising negative impacts of travel.

We are committed to finding and implementing maintainable strategies which include developing teaching resources, offsetting carbon emissions, benefitting local economies, protecting local cultures and becoming ‘Plastic Clever’ travellers.

We can’t do it alone. Will you join us?

“Discover the World Education are a fantastic company to use as a full-time teacher when planning a trip. They make everything incredibly simple and totally minimise stress.”

Free time in Rome

Upon arriving in Rome you will immediately get your first taste of the architecture and vibrant mix of culture that makes Rome the iconic urban metropolis it is known for being. You will have free time to get to know the city and perhaps see some of the iconic key sites of Rome.

After some time exploring the city, you will get your first taste of that tasty Italian cuisine before a good night’s sleep ready for your first full day in Rome.

Mussolini‘s fascist vision

Day 2 begins in the EUR district, which is renowned for Fascist-era architecture. This area was initially dreamt up by Mussolini in the 1930s to celebrate 20 years of fascism by opening a grand new city centre. Now, 20th-century history and modern Roman life perfectly combine as alongside the buildings and statues of Mussolini’s imagination and artwork honouring the fascists even after their fall, is a range of high-end restaurants, the headquarters of Italian fashion house Fendi and even a filming location for some of Hollywood’s biggest blockbusters.

One of the star attractions of the district is the Colosseo Quadrato or Square Colosseum. Students will be in awe of this modern building, which is a masterpiece of rationalist architecture with its rows of 216 arches. The building was completed in 1943, just before the fall of the fascist party. For most of its history, the building stood unoccupied. Today, the building is the headquarters of Fendi and regularly hosts contemporary art exhibitions.

Next, you will visit Foro Italico, the renowned sports complex. Built between 1928 and 1938 as the Foro Mussolini (which means Mussolini’s Forum), was intended to be the jewel in fascist Italy’s bid to host the Summer Olympic Games of 1940 in Rome. This vision wouldn’t be carried out until 1960 when Rome did host the Olympics. Nowadays Foro Italico has not lost any of its draw, as it now hosts the Italian Open and Italy national rugby union team.

Here, students will also find Mussolini’s Obelisk. This huge marble structure is not only monumental for its height and weight, but it is also the only public commemoration of Mussolini, as when after the Second World War, all memorabilia of Mussolini was removed, it was impossible to delete the writings on the 36M high memorial.

The final stop of the EUR District, is another icon of the Fascist era, the Basilica of St Peter & Paul. Created for the World Exhibition (that never happened), the building started in 1939, but quickly halted because of the war and was not completed until 1955 and became a parish church three years later.

After a busy day, immersing yourself in the Fascist vision of the EUR District, you will have a chance to enjoy some delicious Italian cuisine!

Circeo National Park

Founded in 1934, Circeo National Park was established by order of Mussolini, to preserve the last area of Pontine Marshes which were being reclaimed during this period. Led by the fascist government, the marshlands were drained and cleared to settle hundreds of families.

Students will learn all about the reclaiming of the marshlands in the Piana delle Orme land reclamation and the agriculture museum in the park. At the museum, the recreation of the building and vehicles set the scene and help to immerse students in their learnings.

One of the outcomes of this marshland being drained was that agriculture now thrives in the area. You will see this first hand at the Casearia Bianca buffalo dairy farm and vineyard tour where you will stop for lunch.

Next, students will get a chance to explore the sandy dunes of the Circeo Beaches, before heading to the coastal town of Sabaudia, a live example of one of the towns built on the reclaimed marshland, just an hour and a half south of Rome. The town features plenty of fascist architecture for students to explore.

It is time for your last taste of a beautiful Italian dinner ahead of your final day in Rome.

Museum of the Liberation of Rome

After a few days of getting to really understand the fascist vision, it is time to see what came next by visiting the Museum of the Liberation of Rome.

That said, the building the museum stands in is also steeped in history. Previously home to the German Embassy’s Cultural Office, the German link does not stop there. In the first half of 1944, the SS used the building to torture members of the Italian Resistance. On 4 June 1944, the day of the Liberation of Rome, the population entered the building and freed the prisoners who remained.

Now, the museum remembers and educates on, not only the turbulent history of the building itself but also the second world war, fascist rule and the effect on the Roman people.

Bid farewell to Rome as you are transferred for your flight home.

Introducing Italy’s ‘Big Three’ Volcanoes…

Italy is one of the most tectonically active areas in Europe and home to world famous volcanoes that have impacted its people, shaped the landscape, influenced economic activities and increased our understanding of volcanoes.

School Trip Planning Hub

We know that the real job of selling a school trip is down to you and your colleagues so we've collated some helpful resources for you to use to make sure you not only get the buy in from your students and their parents, but also that you have all the details you need to ensure a simple planning process.

Get Started!

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

When in Rome: a new era for the city's ancient sites

A walk through the neighbourhoods of Palatino and Campitelli throws up examples of the innovative archaeology taking place city-wide — an approach that’s helping to weave threads from the Eternal City’s ancient past into modern-day life.

I’m used to looking down when I’m at the Colosseum , but not today. Thanks to a new itinerary allowing access to its subterranean chambers, I’m looking up from the underground spaces where gladiators and wild beasts waited before entering the stadium. Walking through dark corridors, you can feel the horror and the drama that once unfurled here: the terror of the animals, the adrenaline of the gladiators about to fight for their lives, the roar of the crowds. Gazing up through the lift shafts at the seating above, suddenly the violence feels real.

Two millennia since its heyday, the Roman Empire is constantly throwing up new surprises. The Domus Aurea, Nero’s former palace, opens new rooms as and when they’re excavated, and digs at the Circus Maximus have unearthed underground shops. In 2019, the Domus Transitoria — Nero’s other home, on the Palatine Hill — opened to the public.

It’s not just the city’s big-name attractions revealing fresh surprises, either. Earlier this summer, it became possible for the first time in centuries to walk the Aurelian Walls, built in the third century and expanded in AD 401. Seemingly impervious to attack, the fortifications were destroyed by 19th-century Romans intent on urban expansion, reducing much of the walls to fragments.

“Lots of cities have walls, but we have the Forum and Colosseum in Rome, so people think ‘walls — meh’”, says archaeological curator Antonella Gallitto. We’re walking a newly opened stretch of the Aurelian Walls at the top of Via Veneto. As we stroll — elegant palazzos one side, the tall pines of the Borghese Gardens the other, she tells stories of the walls: how they saved Rome countless times against invasion, how 19th-century artists set up ateliers in the towers, and how 20th-century squatters tried to buy them for housing. The Aurelian Walls are anything but forgettable.

They’re just one among a flurry of new openings this year. In September, the Horti Lamiani — the gardens of emperors Caligula and Claudius — were revealed beneath an office block in Piazza Vittorio. A painstaking excavation has revealed hints of past decadence — ostrich, bear and lion bones — and some of the 90,000 pieces of painted wall have been reconstructed to form a panel depicting a port scene. “It’s a new approach, integrating the past into the modern city,” says director Mirella Serlorenzi. “We’re not taking [the remains] away to a museum. We’re giving the city back its history.”

A similar project has opened over on the Aventine Hill, home to the Roman aristocracy for two thousand years. Digs have revealed an ancient domus (mansion) below a block of flats, but instead of having the remains removed, the owners of the site donated the basement to the city. Twice-monthly tours now showcase this grand, first-century villa.

But perhaps the year’s biggest opening was the Mausoleum of Augustus , where Rome’s first emperor was buried, along with a number of his successors, including Caligula and Claudius. I meet with Sebastiano La Manna, director of the restoration, to walk around the inner sanctum, in which the emperors were buried. The air sizzles with intrigue. “That’s Tiberius,” he says casually, pointing at a broken slab of marble inscribed with Latin. We also pass the resting place of Augustus’s sister, Octavia Minor, and his prodigy, Marcellus. “It’s emotional,” Sebastiano admits, noticing me well up.

Guided tours of the site weave the strands of history together. We see elegant turn-of-the-century marble staircases, fascist graffiti and Roman vaulting, as perfect today as it was in 29 BC. The Eternal City is constantly changing, and this year, we’re part of it.

How to do it: Private tour guide Agnes Crawford offers three-hour bespoke tours from £258, excluding entrance fees.

Published in the November 2021 issue of National Geographic Traveller (UK)

Follow us on social media

Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

Fuel their curiosity with your gift

Related topics.

- ARCHAEOLOGY

- HISTORIC PRESERVATION

- HISTORIC SITES

- ANCIENT HISTORY

You May Also Like

Inside the secret world of the Hopewell Mounds—our newest World Heritage site

In Tajikistan, discover the ruins of a once mighty Silk Road kingdom

Take a tour of the Maya underworld—if you dare

See these 6 architectural wonders before they disappear

You won’t find these Hawaiian hiking trails in a guidebook

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

History & Culture

- History Magazine

- History & Culture

- Race in America

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Adventures Everywhere

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

20th Century Travel | Viaggia con Noi

Scopri il mondo con 20th Century Travel, un gruppo di agenzie a Roma e Milano pronte a soddisfare ogni tua richiesta e sempre alla...

Is It Legitimate Site?

Protect Your Privacy

Sur.ly Safeguard

Safety status

Server location

Domain Created

15 years ago

Latest check

4 months ago

Child safety

Trustworthiness

MALICIOUS CONTENT INDICATORS

20th.it most likely does not offer any malicious content.

Siteadvisor

SAFEBROWSING

Secure connection support

20th.it provides SSL-encrypted connection.

ADULT CONTENT INDICATORS

20th.it most likely does not offer any adult content.

Popular pages

8 Giorni / 7 Notti Scopri il mondo con 20th Century Travel, un gruppo di agenzia a Roma pronte a soddisfare ogni tua richiesta e sempre alla ricerca delle migliori offerte. Entra anche tu nel mon...

- Things to do

- Museums and Art Galleries

National Gallery of Modern Art

Paul Cezanne, Antonio Canova, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh… Rome’s Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna is one of the best art museums in Italy.

Rome’s Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna (National Gallery of Modern Art) was created in 1883 to hous e the newly unified Italian state’s contemporary works of art . The gallery was originally located in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni until 1915. The collections were then moved to the Palace of Fine Arts, where works of contemporary and modern Italian art are still on display.

Exhibitions

The museum’s collection includes over 5,000 paintings and sculptures , including works of art dating from the neoclassical period to the abstract works from the 1960s .

The permanent exhibitions, housed in enormous halls, are very interesting and include works of art by renowned artists.

The ground floor is dedicated to the nineteenth century, where visitors can find works by Paul Cezanne, Antonio Canova, Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh .

The top floor, on the other hand, is devoted to twentieth century art , including Futurist, Cubist, Dadaist and abstract art movements.

Unlike other contemporary art museums

The Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna offers an impressive collection of Modern Art , with a large number of pieces of art by renowned artists. It is definitely a very interesting museum with a wide range of art movements.

Viale delle Belle Arti, 131.

Tuesday – Sunday: 8:30am – 7:30pm Monday: closed

Permanent collection: Adults: € 10 ( US$ 10.70) EU citizens (ages 18 – 25): € 2 ( US$ 2.10)

Metro station: Flaminio , line A. Buses : 88, 95, 490, and 495.

Nearby places

National Etruscan Museum (378 m) Villa Borghese (575 m) Santa Maria del Popolo (792 m) Piazza del Popolo (872 m) Galleria Borghese (889 m)

You may also be interested in

Crypta balbi.

As one of the four branches of the National Museum of Rome, the Crypta Balbi offers its visitors a historical trip through Rome’s past thanks to the excavations carried out on its site.

Palazzo Barberini

Palazzo Barberini is an imposing Baroque building that houses the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, the National Gallery of Ancient Art. Commissioned by Pope Urban VIII, the mansion was the most elegant and luxurious villa of the period.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti