BOTSWANA TOURISM

Contact details, directions to botswana tourism, directions from botswana tourism, business categories:.

- Travel & Tourism: All : Botswana

Your details incorrect?

- IOL Business

- Advertise with us

- Privacy & Legal

- Accommodation

- Conferencing

- Tour Operators/GSA's

- Air Charter

- Airport Info

- Associations

- Bank / Credit Card Authorisations

- Chauffeur & Transfers

- Coach Charter

- Country Guides

- Cruise Destinations

- Forex & Insurance

- Game Lodges

- Hotel Groups

- Rail Destinations

- Rail / Intercity

- Ski Destinations

- Tourism Offices

- Tourist Attractions

- Unique Services

- Visa / Passport / Health

- Competition

- GSA Digimag

- About The GSA

- Advertise with us

- Product Search

- Category Search

GSA Galaxy helps you search faster and find more accurate results. Start typing the name of the listing, city or web reference to bring up the results you are looking for.

Know what you are looking for, but not who you are looking for? Use the category search to jump to a directory list.

Our comprehensive Country Guides contain everything from Visa Information to Tour Operators. Start planning your international holiday by typing the country that you are looking for.

Botswana Tourism Office

Contact details, botswana tourism organisation.

Extremely dramatic, Botswana's landscape features striking salt pans, diamond-rich deserts and fertile flood plains which teem with game. The north, in particular, offers superb wildlife-watching opportunities, making this one of southern Africa's top safari destinations.

For visa and country information visit our Botswana Country Guide .

Accreditations

Connect Socially

BOTSWANA TOURISM BOARD

Contact details, directions to botswana tourism board, directions from botswana tourism board, business categories:.

- Tourism: All : Botswana

Your details incorrect?

- IOL Business

- Advertise with us

- Privacy & Legal

- You are here:

Botswana Tourism Organisation

Social media channels

Primary organisation type

Tourism Organisation

Member number

http://www.botswanatourism.co.bw/

Botswana is well known for having some of the best wilderness and wildlife areas on the African continent. With a full 38 % of its total land area devoted to national parks, reserves and wildlife management areas travel through many parts of the country has the feeling of moving through an immense Nature wonderland. For the most part parks are unfenced, allowing animals to roam wild and free.

Botswana is a rarity in our overpopulated, over-developed world.

Experience the stunning beauty of the world’s largest intact inland Delta – the Okavango; the unimaginable vastness of the world’s second largest game reserve – the Central Kalahari Game Reserve; the isolation and other-worldliness of the Makgadikgadi – uninhabited pans the size of Portugal; and the astoundingly prolific wildlife of the Chobe National Park.

Botswana is the last stronghold for a number of endangered bird and mammal species, including Wild Dog, Cheetah, Brown Hyena, Cape Vulture, Wattled Crane, Kori Bustard, and Pel’s Fishing Owl. This makes your safari experience even more memorable, and at times you will feel simply surrounded by wild animals.

The first – and most lasting impressions – will be of vast expanses of uninhabited wilderness stretching from horizon to horizon, the sensation of limitless space, astoundingly rich wildlife and bird viewing, night skies littered with stars and heavenly bodies of an unimaginable brilliance, and stunning sunsets of unearthly beauty.

As more and more cultural tourism options are offered, you will be charmed by the people of Botswana, visiting their villages and experiencing first-hand their rich cultural heritage. But perhaps most of all, Botswana’s greatest gift is its ability to put us in touch with our natural selves.

Activities offered

- Accommodation

- Mobile Safaris

- Self-Drive Holidays

- Riding Safaris

- Photography

- Safaris - Fixed Camp

- Bird Watching

Where we operate

Where we’re based.

- Cleaning Equipment & Services

- Department Of Tourism

Department Of Tourism - Gaborone

- Verified Listing

- Monday: 07:30 - 16:30

- Tuesday: 07:30 - 16:30

- Wednesday: 07:30 - 16:30

- Thursday: 07:30 - 16:30

- Friday: 07:30 - 16:30

- Saturday: Closed

- Sunday: Closed

Questions & Answers

Verified business, related searches.

- Cleaning Equipment & Services in Gaborone

- General Office Services in Gaborone

- Printing in Gaborone

- Secretarial Services in Gaborone

- Internet Service Providers in Gaborone

- Audit and Accounting in Gaborone

- Air Transport in Gaborone

- Logistics in Gaborone

- Vehicle Services in Gaborone

- Shipping & Port Agent in Gaborone

Botswana Tourism Board Contact details

Find the Botswana Tourism Board Contact Details, Phone Numbers, Email and Postal Address.

Table of Contents

Botswana Tourism Board Contacts details, Directions, Address and Location provided below are undoubtedly useful and convenient for obtaining critical information from remote, off-campus-areas. Continue reading for physical Address, Phone, email, fax, box numbers, and social media presence among other vital contacts to connect with Botswana Tourism Board.

Botswana Tourism Board Contacts details

Headquarters.

Use this page to send us any comments and suggestions you may have about this website as well as make any other enquiries about our products, destinations, activities and so on. A qualified team of people will handle your request and will contact you shortly.

If you would like to visit or call: Botswana Tourism Organisation Plot 50676, Fairgrounds Office Park Block B, Ground Floor Gaborone, Botswana Tel: +267 391 3111 Fax: +267 395 9220

READ ALSO: Jobs in Botswana

Go to our Homepage To Get Relevant Information.

For more information Visit http://www.gov.bw/

Related posts.

- SAIU Courses offered & Admission

- Kearsney College online Application, Courses, fees, Contacts

- Apply & register – Unisa, University of South Africa

- National Microfinance Bank (NMB) Contact, Phone Numbers

- How to resign from a job

- MWECAU Prospectus | Mwenge Catholic University (MWECAU)

Discover Your Next Career Move: – Nafasi za kazi mpya Leo, Ajira Tanzania, Zoom Tanzania | Jobs in Tanzania. Ajira Mpya, Ajira Zetu, Ajira Portal TZ, yako 360, Jobs and Vacancies in Tanzania.

- Post a Tender

Jobs by Categories

- Accounting Jobs

- Administration Jobs

- Banking and Finance Jobs

- Clearing and Forwarding Jobs

- Driver Jobs

- Education and Teaching Jobs

- Embassy Jobs

- Engineering Jobs

- Government Jobs

- Hospitality and Tourism Jobs

- Human Resources jobs

- Information Technology Jobs

- Logistics & Transportation Jobs

- Mining Jobs

- NGO and Social Work Jobs

- Procurement and supply jobs

- Sales and Marketing Jobs

OTHER SERVICES

- CV Writing Service

- ZA-Bursaries

- Scholarships

- Career Guide

- NECTA Results

- Advertise Here

- Call For Interview

- Ajira Portal: Latest Jobs

- Tanzania Jobs

- Jobs in Zambia

- Jobs in Kenya

- Tenders in Tanzania

- Other Countries Jobs

Send to a friend

Botswana - Apply for Tourist Enterprise Licence or Permit (TEL)

- 1 Procedure

- 2 Required Documents

- 3 Office Locations & Contacts

- 4 Eligibility

- 7 Documents to Use

- 8 Sample Documents

- 9 Processing Time

- 10 Related Videos

- 11 Instructions

- 12 Required Information

- 13 Need for the Document

- 14 Information which might help

- 15 Other uses of the Document/Certificate

- 16 External Links

Procedure Edit

Apply In-Person

- The application for Tourist Enterprise Licence or Permit (TEL), shall be made to the Department of Tourism Offices, which is under the Ministry of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation and Tourism. Ministry contact details .

- Applicants are required to collect and complete the Application Form for Tourism Enterprise Licence.Copies of these forms are available for free at any Department of Tourism headquarter or regional Offices, or directly download it using this link; Application Form for Tourism Enterprise Licence Categories A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J & L

- The application form duly completed in all respect, and the supporting documentation should be submitted to the nearest Department of Tourism Regional Office, Licensing and Registration unit.

- If the application is submitted on your behalf by a consultant, the applicant should include a letter naming the consultant as their representative. The applicant should include their postal address, telephone, and fax numbers.

- Upon receipt of the application file, the Licensing and Registration officer will verify if all the necessary information and documentation has been provided and that the applications comply with the selection criteria before registering the file.

- Applicants will be issued with an acknowledgment letter as proof of submission of the application.

- The application file will be forwarded to the Tourism Industry Licensing Committee for evaluation and consideration, which is within 30 days.

- Applicants will then be notified of the outcome of their application by way of a letter.

- If approved the license /permit will be drawn up as directed by the committee, signed and stamped, and made available to be issued to the applicant.

- The applicant will be required to produce a proof of identity document and acknowledgment letter and pay the license fee as mentioned under the “Fees” section of this page while collecting the Tourist Enterprise Licence or Permit (TEL).

Required Documents Edit

- A detailed Business Plan (guidelines provided).

- A certified copy of the Certificate of Incorporation and/or a copy of the Certificate of Registration of the business trading name.

- Certified copies of share certificates.

- Companies Proclamation i.e. Form 2. If the land was acquired for a purpose other than for the tourism project an application for change of use or planning permission from local authorities or land board is required

- Certified copies of valid Omang or passport of the shareholders and for expatriate employees, copies of resident/work permits.

- Title deed or lease agreement/rental agreement- if the land was acquired for a different purpose other than for the project you wish to undertake you should apply for a change of use or planning permission, from your local authorities or Land Board.

- Details of vehicles. i.e. Vehicle Registration and Road Worthiness Certificates (Botswana Registered) for Categories C & E

- Submission of an Environmental Management Plan/Environmental Impact Analysis approved by the Department of Environmental Affairs (Categories A, B, J)

- Occupation Permit (Categories A & B)

- Consent from land authorities for sub-leases and/or rental agreements/transfer of leases/title deeds

- Satisfactory inspection reports of the premises (department of tourism & environmental health)

- Approved technical / building / architectural plans, for a building project such as a Hotel, Guesthouse, lodge, camp, etc. (Categories A & B)

- Curriculum vitae for the shareholders

Please Note :

- The Vetting Committee may request additional documents as they deem necessary

- (Please submit ten (10) copies of all the requirements however only one set of the building plans must be submitted)

Office Locations & Contacts Edit

Ministry of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation, and Tourism Private Bag BO 199 Gaborone, Botswana Address: Plot 13064 Government Enclave Tel: +267 3647900 / +267 391 4955 Fax: +267 3951092 Email: [email protected] Toll-free Number: 0800 600 734 Department of Tourism Address: 2nd floor, Standard House The Main Mall, Queens Road Private Bag 0047 Gaborone Botswana Tel. (+267) 3953024 Fax. (+267) 3908675 Ministry contact details Department of Tourism Offices Regional contacts

- Gaborone: (+267) 3953024

- Maun: (+267) 6860492

- Gantsi: (+267) 6596733

- Tsabong: (+267) 6540833

- Selibe-Phikwe: (+267) 2611023

- Francistown: (+267) 2418192

- Serowe: (+267) 4631161

- Kasane: (+267) 6250357

Opening Hours of Operation: 07:30 – 16:30, Monday to Friday, except on Public Holidays.

Eligibility Edit

The eligibility criteria are as follows; Categories A & B License

- This service is open to both citizens and non-citizens in Botswana EXCEPT for the following tourist enterprises; guesthouses (corporate guest houses and Bed & Breakfast), camp and caravan sites.

Categories C, E & F License

- 100% citizens or wholly-owned citizen companies.

Categories D, G, J, K & L License

- Citizens and non-citizens.

Tourism I License

- Operators based outside the country

- There is no application fee charged. Upon approval the following license fee is chargeable,

- The license fee is BWP 1000 or its equivalent for {categories A/C/D/}

- The license fee is BWP 1500 or its equivalent for {category B}

- The license fee is BWP 500 or its equivalent for {categories E/F/}

- The license fee is BWP 1500 or its equivalent for {categories G/H}

- Category I License fees payable are USD 2000.00 or Botswana Pula (BWP) equivalent.

Validity Edit

- The license is valid for one year from the date of issue and renewable thereafter

Documents to Use Edit

- Application Form for Tourism Enterprise Licence Categories A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J & L

Sample Documents Edit

Processing time edit.

- The time frame for processing the application is within 30 days from the time the application is received by the TILC.

Related Videos Edit

Instructions edit.

Tourism License Categories Tourism operations are divided into ten different categories, each of which requires a separate license:

- A License : Accommodations on a fixed site; such as hotels, motels, guesthouses (including corporate guesthouses), bed and breakfast, self-catering apartments, backpacker tourist accommodation, campsites, outside protected areas; and cultural villages, including timeshare facilities.

- B License : Accommodation on a fixed site; such as photographic/hunting camps and lodges, and public camping sites or caravan sites that offer game drives and other outdoor activities; within wildlife management areas and protected areas, including timeshare facilities.

- C License : Off-site facilities, such as mobile safari operators that receive and transport travelers and guests within protected areas.

- D License : Logistics and travel arrangements for clients without accommodation (whether fixed or not) or other tourist services.

- E License : Transport to tourist attractions, including road transfer activities outside protected areas.

- F License : Motor-boating activities outside of protected areas, private reserves or wildlife management areas.

- G License : Other enterprises (excluding air charter companies and car rentals) that conduct tourism-related activities (e.g., hot-air ballooning, cycling, bungee jumping, etc.)

- H License : Operations that offer mekoro (dugout canoe) activities.

- I License: Foreign-based companies offering tourism-related activities in Botswana. License holders may conduct operations in game reserves or national parks but may hand over to a Botswana licensed operator if entering protected areas.

- J License : Houseboat operations: mobile self-contained accommodation on bodies of water.

(Please refer to wikiprocedure website for full procedure details on how to apply for each license, individually listed above)

Required Information Edit

- Name of Company/Applicant name

- Trading name of the establishment

- Contact details (Postal Address/Physical Address/Telephone No/Fax No/E-mail)

- Company Secretaries and their contact numbers

- Certificate of Incorporation No/ date of issue

- The principal business of the company

- Details of the shareholders of the company: (attach separate sheet if necessary)

- Details of Directors of the Company

- Categories of license you are applying for

- Declaration by the applicant

Need for the Document Edit

- A tourist enterprise license is a permit issued to entities that operate businesses or services that directly deal with tourists e.g. Travel agencies, Tourist Accommodation facilities. Find the description for all the license categories as mentioned under the “Instructions” section above.

Information which might help Edit

- Guidelines for Tourist Related Accommodation

- Guidelines for Licensing of Agro-Tourism Operation

- Guidelines for Domestic Guest House

Other uses of the Document/Certificate Edit

External links edit, others edit.

Embassy of the Republic of

Botswana in Sweden

The Embassy invites you to visit the links below for information on tourism in Botswana. The Botswana Tourism Organisation link provides useful information for tourists. You are welcome to visit the Embassy for some tourist brochures.

- Botswana Tourism Organisation

- This is Botswana

- Discover Botswana

Beautiful Botswana

Botswana is not only a vast country – covering more than 580,000 sq km – but also one of the world’s least densely populated. About 70 per cent of the country is formed by the Kalahari Desert, which extends across Botswana’s central belt. An astonishing 37 per cent of the nation’s total land area – equivalent to a country the size of New Zealand – has been set aside as national parks, wildlife reserves or wildlife management areas.

View the map

The Tourism Organisation

The Botswana Tourism Organisation was set up by the government to market tourist products and grade and classify tourist accommodation as well as to promote investment in the tourism sector. With great success, the organisation is focused on providing high standards and tourism strategies that exceed customer expectations as well as building customer confidence internationally.

Botswana's Official Tourism Website

National Airline

Botswana is an outstanding tourism and business destination. Air Botswana, the national airline, brings visitors to this special part of Africa from Johannesburg, Cape Town, Harare and Lusaka. Passengers arriving on long-haul fl ights in Johannesburg can readily transfer to Air Botswana for onward jet fl ights direct to Maun, on the edge of the Okavango Delta, or direct to Kasane, gateway to Chobe National Park.

Air Botswana Official Website

© Copyright Embassy of Botswana in Stockholm, 2024

Social enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): a means to an end

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Josiah Nii Adu Quaye 1 ,

- Jamie P. Halsall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4555-7470 3 ,

- Ernest Christian Winful 2 ,

- Michael Snowden 3 ,

- Frank Frimpong Opuni 4 ,

- Denis Hyams-Ssekasi 5 ,

- Emelia Ohene Afriyie 6 ,

- Kofi Opoku-Asante 2 ,

- Elikem Chosniel Ocloo 4 &

- Bethany Fairhurst 7

Ghana is regarded as one of the main nations driving social enterprise development in all of Africa, despite the lack of a policy for the social enterprise sub-sector. Regardless of these trailblazing initiatives, the sub-sector is still young and vulnerable. As a result, the time is right for the government to implement policy reforms to expedite the growth of the sub-sector, which offers an alternative business model for the achievement of the social and environmental goals embodied in the global goals. All nations are urged to take immediate action in response to the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which offer a global framework for achieving global development while balancing social, economic, and environmental sustainability. The methodology adopted is qualitative in nature, whereby focus group discussions were held, bringing together key stakeholders from the social enterprise sector, industry, academia, and civil society organisations (CSOs) to provide insights into how social enterprises will contribute to SDG achievement. This paper aims to generate new insights into how social enterprises can provide a solution to the UN’s SDGs from the Ghanaian perspective. Our findings reveal a strong link between solving social problems through social businesses and achieving the SDGs, and that social enterprises represent an ideal business model for achieving the SDGs. Their mission-driven approach, innovative solutions, focus on empowerment and inclusion, utilisation of market mechanisms, collaboration and partnership, and understanding and knowledge of local contexts collectively position social enterprises as powerful catalysts for sustainable development.

Explore related subjects

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is generally accepted that social enterprises have a role to play in driving the delivery of the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as illustrated by the assertions of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015, and reiterated by Kumi ( 2019 ), Mediavilla and Garcia-Arias ( 2019 ), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) ( 2018 ). However, the importance of this role has received significant attention recently, as expressed by the recent and historic resolution adopted unopposed by the UN General Assembly (2023), which was unequivocal in its support for social enterprises and encourages member states to promote and support them as a distinct strategy to achieve the UN’s SDGs.

Given the universal and multifaceted nature of the SDGs, collaboration among governments, the business sector, academia, civil society organisations (CSOs), and philanthropic institutions has become imperative (Agenda, 2015 ). Consequently, stakeholders have engaged in discussions to formulate strategies for implementing the SDGs. The 17 SDGs were officially adopted with the aim of eradicating poverty and hunger, preserving the environment, and promoting prosperity by 2030. However, with only 8 years remaining until the deadline set by the UN General Assembly, many African nations continue to face challenges in achieving all 17 goals. As a result, there has been increased interest and inquiries regarding the role of social enterprises as key stakeholders in SDG implementation at both global and national levels (Arhin, 2016 ; Salamon & Haddock, 2015 ).

Over time, various entities such as the UN, private, public, and third sectors have recognised social enterprise as a platform for fostering interconnectedness. Social Enterprise is now documented to have emerged from Europe and the United States of America concurrently in 1990, and is suggested to relate to a new entrepreneurial focus for achieving social objectives. Rahman and Sultana ( 2020 ) record it as a hybrid business model that responds to the failure of government policies and philanthropic efforts to provide sustainable solutions to social and environmental problems. (Rahman & Sultana, 2020 ) further describe it as a social objective-driven or cause-driven model utilising both philanthropic and business principles to produce goods and services while ensuring productive and commercial viability.

Social enterprise concepts have gained popularity among policymakers, practitioners, and researchers. Since 1990 when the concept gained traction, there have been varied conceptions of the enterprise model with two views dominating the discourse – the Anglo-Saxon and the European model (Chaves Ávila & Monzón Campos, 2018 ; Defourny & Nyssens, 2017 ). Each model exhibits a different attribute with four general models – (1) the commercial non-profit; (2) the social mission-oriented enterprise, which focuses on social issues and objectives; (3) the social entrepreneur model interested in social innovation; and (4) the European model, which relates to a private non-profit organisation.

Social enterprise, at its core, offers solutions to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues of today (Halsall et al., 2020 , 2022 ; Oberoi et al., 2020 , 2022 ; Opuni et al., 2022 ; Winful et al., 2022 ). However, limited scientific research exists on the specific role of social entrepreneurship in promoting the SDGs, with much of the existing literature relying on secondary sources or anecdotal evidence (e.g. Callias et al., 2017 ; OECD, 2018 ; UNDP, 2017 ). Furthermore, there is a knowledge gap regarding the social enterprise sector in Ghana, despite the country’s rich history of investing in social issues. To expedite progress towards achieving the SDGs, this article seeks to examine the challenges faced by social entrepreneurs in Ghana and their contributions to SDG attainment.

2 Problem statement

The pursuit of sustainable development has become an urgent priority for nations worldwide as they confront pressing social, economic, and environmental challenges. In this context, the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have emerged as a comprehensive framework guiding global efforts towards a more equitable and sustainable future. As countries navigate the path towards achieving these goals, the role of social enterprises is garnering increasing attention and recognition.

Social enterprises, with their distinctive blend of social and business objectives, have emerged as powerful agents of change. These purpose-driven organisations leverage market-driven approaches to address social and environmental issues, making them an appealing solution for fostering inclusive economic growth and sustainable development. Through innovative business models, social enterprises strive to tackle complex problems such as poverty, inequality, climate change, and access to education and healthcare (Boyer et al., 2023 ; Lutz, 2019 ; Maduro et al., 2018 ; Muñoz et al., 2022 ).

The intersection between social enterprise and the SDGs presents a compelling opportunity for synergistic progress. The SDGs provide a roadmap for global development, encompassing 17 interconnected goals that span diverse social, economic, and environmental dimensions. Social enterprises, with their inherent focus on addressing societal challenges, are well-positioned to contribute to the achievement of these goals. Their unique ability to generate social impact while maintaining financial sustainability offers a promising avenue for addressing systemic issues and driving transformative change (Snowden et al., 2021 ).

In the context of Ghana, many companies have downsized their operations, leading to job insecurity. Given the economic repercussions of COVID-19 and the subsequent recession, adopting business models that promote environmental sustainability and alleviate economic hardships is essential. However, the bureaucratic nature of the educational system poses challenges to its agility and ability to keep up with current trends and effectively address societal issues. A recent World Bank report titled “Youth employment programs in Ghana: Options for effective policy making and implementation” identifies significant industries with potential for generating employment opportunities for Ghanaian youth, including agriculture, entrepreneurship, apprenticeships, construction, tourism, and sports (Dadzie et al., 2020 ). Unfortunately, few universities in the country provide social enterprise training.

Social economists have recently emphasised their responsibility for managing the planet’s physical environment (Novkovic & Webb, 2014 ; Ridley-Duff & Wren, 2018 ). This acknowledgement has been driven by institutional support for sustainable development from the government, cooperatives, and the business sector (Brakman Reiser, 2011 ; Mills & Davies, 2013 ). Recognising personal, societal, and environmental responsibilities necessitates a shift in business models.

As reflected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights ( 1948 ), every individual has the right to a secure and sheltered home, clean drinking water, fresh air, and access to nutritious food (natural resources), as well as the ability to engage in various activities (manufactured wealth). Businesses striving to improve public health and wellbeing and to provide universal access to desired goods or services contribute to the creation of public goods. In the past three decades, several governments have transitioned from directly producing to commissioning these goods through public service social enterprises (PSSEs), which are companies directly or indirectly owned, financed, and governed by the government (Hood, 1995 ; Ridley-Duff & Wren, 2018 ; Sepulveda, 2015 ). Recently, social enterprises have evolved from government control to increased involvement from the private sector. The social enterprise sub-sector primarily develops innovative approaches to address social, health, and environmental challenges by employing appropriate technologies. These technologies, applied in agriculture, ecology, and healthcare, create employment opportunities.

The European Social Enterprise Monitor Report 2020–2021 uncovered a significant gap in impact assessment within social enterprises (Dupain et al., 2021 ). Less than 60% of these enterprises assess their impact targets, and a mere 40% consider the SDGs in their analysis (Diaz-Sarachaga & Ariza-Montes, 2022 ). This is a crucial issue to address due to the lack of comprehensive information on the social enterprise sub-sector, including its scope, market potential, needs, and capacity to tackle the substantial societal challenges faced by Ghana and other African nations. Furthermore, governments face formidable obstacles in finding long-term solutions to challenges presented. The potential solutions offered by social enterprises justify the need to promote awareness campaigns, provide social entrepreneur training, capacity building, and the integration of social entrepreneurship into secondary, further, and higher education frameworks. These efforts will enhance the sustainability of national development goals, and the urgency of the COVID-19 pandemic underscores the importance of fostering partnerships between corporations and social enterprises, with a focus on community-centered approaches.

Anaya et al. ( 2023 ) discuss the positive effect of community interventions in teaching social entrepreneurship to provide sustainable solutions to social problems; however, they do not explicitly link social enterprise as a model for achieving the SDGs. Bausch et al. ( 2023 ), in contrast, explore the transformational potential of social enterprises and view social enterprise as a viable way of achieving the SDGs. (Ilchenko, 2023 ) positions social entrepreneurship as an innovative model with the capacity to solve social problems, emphasising the ability of social enterprises to introduce social, economic, and innovative solutions to social problems.

The scope of the UN SDGs is broad, encompassing human rights, environmental movements, employment, education, population, the fight against poverty, and the promotion of peace (Mirza, 2016 ). Moreover, the 17 SDGs and their 169 targets are at the core of the 2030 Agenda, and their scope and ambition have been strengthened in relation to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) adopted in 2000 (Laveuve, 2022 ). The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987 , p. 41). This concept has been carried forward into the present day and the future via the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and this agenda’s constitutive SDGs (Chowa et al., 2023 ), which are underpinned by five key foci: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership.

The status of regional sustainable development is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires multidimensional attention. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognises the importance of the regional dimension in implementing and reviewing sustainable development (Medina-Hernández et al., 2023 ). The bottom-up approach, which involves solving social problems from within the local community, has been recommended by researchers as an ideal way of achieving regional SDGs. Various approaches to regional development have been explored, with an emphasis on the bottom-up approach and the involvement of local communities in decision making. Sustainable development is seen as a continuous and irreversible process that involves balancing social, economic, environmental, and spatial factors (Veckalne & Tambovceva, 2022 ). Anyshchenko et al. ( 2022 ) amplify the importance of creating national development plans that utilise a regional approach and benefit not only the economy and environment but also the inhabitants of the regions.

The purpose of this article is to examine the role of social enterprise in advancing the SDGs, specifically in the context of Ghana. The authors seek to outline and emphasise social enterprise as an efficient and effective way to integrate social solutions into the national development plan of Ghana. This is intended to provide the foundation and serve as a catalyst for adopting social enterprise in achieving the SDGs in the African subregion. Ghana serves as an illustrative case due to its vibrant social enterprise sector and strong commitment to sustainable development. By exploring the experiences, contributions, and challenges faced by social enterprises in Ghana, the authors aim to highlight their potential as catalysts for sustainable development, and to identify strategies to unlock their full potential (Adeleye et al., 2020 ; Appah, 2020 ; Arhin, 2016 ; Mutuku et al., 2020 ; Zadra & Pesce, 2019 ). The contribution of this paper is to:

Provide a valuable insight into leveraging social enterprises for achieving the SDGs in the Ghanaian context. This is one of the first papers to explore the interlocking relationships of SDGs and social enterprise in a Ghana public policy setting.

Update the current models for the SDGs and social enterprise framework. The authors present two updated models (Figs. 1 and 2 ) that can be utilised by public policy makers.

Demonstrate how social enterprise can act as a positive catalyst for Ghana’s economic development, from a social development perspective. This third contribution enhances the current thinking from the Government of Ghana’s vision of “Building a sustainable entrepreneurial nation: Fiscal consolidation and job creation”, which was presented to parliament in November 2021 (Ofori-Atta, 2021 ).

Challenges in Formulating and Implementing SDGs in Ghana.(Adapted from: Ministry of Environment Science and Technology, 2012)

Characteristics of social enterprises

3 Literature review and related work

3.1 social enterprise in ghana.

Social enterprise is intricately connected to the political, social, and economic systems of sovereign states, and Ghana’s social entrepreneurship sector is no exception (Oduro et al., 2022 ). The socioeconomic inequality prevalent in Ghana significantly affects the life prospects of its young population. Despite a national unemployment rate of 5%, youth unemployment (ages 15–35) is much higher, standing at 12%, with an additional 28% classified as discouraged workers. In the absence of unemployment benefits, the informal economy becomes the primary source of livelihood for many young individuals, many of whom face hazardous working conditions. Approximately 230,000 Ghanaians attempt to enter the labour market annually; however, the formal economy can only absorb about 2% of this figure, leaving 225,000 individuals without employment opportunities (Dadzie et al., 2020 ). Moreover, about 50% of those employed are underemployed or lack the necessary entrepreneurial skills to be self-employed. In the first three quarters of 2022, the average employment rate reached nearly 11 million individuals, while the third quarter saw 1.76 million persons unemployed, with female unemployment twice that of males (GSS, 2022 ).

The existing infrastructure poses significant barriers to startups and small to medium-scale enterprises, hindering socioeconomic growth and further exacerbated by the socioeconomic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Considering the global economic downturn, it is imperative to develop new strategies for equipping the workforce with essential employability skills. Communities must be proactive in responding to the challenges posed by the pandemic and work towards long-term solutions. The World Bank has identified agribusiness, entrepreneurship, apprenticeships, construction, tourism, and sports as key sectors that can enhance youth employment prospects in Ghana (Dadzie et al., 2020 ). However, Ghanaian universities have failed to incorporate societal skill development in these areas, particularly in providing career guidance, work-based learning opportunities, entrepreneurship training, coaching, and mentorship to equip young people with the skills aligned with the global skills framework. The higher education sector must reassess its programmes, teaching approaches, and coaching methods to effectively address these challenges.

In Ghana, social enterprises predominantly operate in the education and agriculture sectors. Education-focused social enterprises are primarily concentrated in Accra, while agricultural social enterprises are more prevalent in the northern regions. The growth of Ghana’s social enterprise sector can be attributed to international NGO programmes and remittances from the diaspora. According to research by the British Council ( 2015 ), Ghana could potentially have up to 26,000 social enterprises. Although the concept of social entrepreneurship is relatively new to Ghana, the country has a long history of activities that align with the principles of social enterprise. Therefore, it is crucial for Ghana to establish a clear definition of social enterprise, which will serve as the foundation for the classification, legal, and regulatory frameworks necessary for its development and growth.

3.2 The current accomplishment of SDGs in Ghana

To assist the implementation of the SDG agenda, Ghana has made progress in developing institutions and putting in place policies and plans, as well as coordinating and collaborating on structures and other pertinent activities. These institutions, however, are frail and have not been able to produce the desired effects. There is still much work to be done to strengthen them, particularly regarding the elimination of environmental bias and addressing the SDGs’ various components in a comprehensive and integrated way.

Planning for national development has a long history in Ghana. In 1919, the Guggisberg Plan, which was the first development strategy, was created and put into action (Birmingham et al., 1966 ). The Economic Recovery Program (ERP)/Structural Adjustment Programs (1983–1999), which were followed by the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs), made up the longest sequence of medium-term stabilisation programmes (Nowak, 1996 ). The Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper was the first PRSP (2000–2002). The others were the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA) (2010–2013), the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda II (GSGDA, 2014–2017), the National Development Plan for Ghana (2017), and the Growth and Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (GPRS II) (2006–2009). Ghana has incorporated the SDGs into its national development plans, including the national budget and government flagship programmes like the “One District, One Factory” initiative, Free Senior High School education policy, “One Village, One Dam” initiative, and Planting for Food and Jobs, among others. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) align with Africa’s Agenda 2063, and its achievement in terms of environmental, human and climate gains and benefits to national, regional, and global peace, prosperity, and stability (Government of Ghana, 2019 ). The integration of SDGs into Ghana’s development agenda is reflected in the nation’s Coordinated Programme of Economic and Social Development Policies (CPESDP), 2017–2024.

The SDGs are the successors to the MDGs, which were established in 2000 (Jayasooria & Yi, 2023 ) to mobilise political and financial support for addressing some of the most pressing issues facing the world, including poverty, hunger, gender inequality, standards of educational provision, diseases, and environmental degradation (Karver et al., 2012 ; Sachs, 2012 ). The Government of Ghana, in its Voluntary National Review Report in June 2019, recognised the role of philanthropic foundations, both locally and globally, in Ghana’s SDG processes. These foundations support the prototyping of innovative solutions for, and the implementation of, the SDGs at various levels through the provision of social financing and catalytic grants. Innovative prototypes have also received support from philanthropic organisations through various partners who provide catalytic grants with the aim of improving outcomes and ensuring the utmost impact. An example of this philanthropic support is the Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors and the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation through the SDG Philanthropy Platform (SDGPP), coordinated by UNDP, which provide grants to social enterprises and NGOs for scalable, innovative and impactful solutions to bringing safe water to communities classified as “hard-to-reach” (Government of Ghana, 2019 ).

Despite the government’s recognition of the important role social enterprise play there is a lack of a clear strategy for the social enterprise sub-sector, even though Ghana is regarded as one of the top nations driving the growth of social enterprise in Africa. Despite these trailblazing initiatives, the subsector is still young and vulnerable. As a result, the time is right for the government to implement legislative changes to hasten the growth of the sub-sector, which offers an alternative business model for the achievement of the social and environmental goals embodied in the global goals. All nations are urged to take immediate action in response to the SDGs, which offer a global framework for achieving global development while balancing social, economic, and environmental sustainability. All societal members, including academics and professionals who are aware of the unique significance of enterprises, are addressed by the SDGs. Organisations can use the 17 SDGs to promote growth, manage risk, draw in funding, and center their efforts on a specific goal. According to the Business & Sustainable Development Commission, by 2030, sustainable business models could provide up to $12 trillion in potential economic output and 380 million new employment opportunities. Fundamentally, the SDGs offer businesses a historic chance to use societal challenges as stepping stones for long-term growth and competitiveness. Social enterprises are crucial to achieving the UN’s new SDGs, according to recent research by Social Enterprise UK. The SDGs are an international call to action to eradicate poverty, safeguard the environment, and guarantee that everyone lives in peace and prosperity by the year 2030. The 17 SDGs recognise the need to balance social, economic, and environmental sustainability in development, and that actions in one area can have an impact on results in other areas. Social enterprise is suggested as an option by the UNDP ( 2020 ).

The COVID-19 pandemic required communities to be responsive and to strive toward developing sustainable solutions, as emphasised by the United Nations ( 2022 ) and the proposal that universities have a key role to play in this process: first, by embedding enterprise initiatives within curricula and developing social enterprise skills, and second, to support social enterprises by providing a pool of expertise for social enterprises to draw upon. Ghana, one of Africa’s most developed and stable economies, is up against several challenges in achieving its SDGs, a scenario compounded by the ongoing COVID-19 conflict. Ghana’s overall costs for attaining the SDGs are anticipated to be $522.3 billion by 2030, with an annual average of $52.2 billion.

3.3 A wider social development context

Africa as a continent has been bounded up in social development democratic public policy frameworks in the postwar period (Daunton, 2023 ; Larrain, 1989 ; Reader, 1997 ). This has been driven by a postwar consensus whereby there was a real call for development to be a social policy initiative to improve citizens’ lives in terms of social, economic, health and environmental status. There have been several studies in the recent past that have investigated social development in the African region. For example, in South Africa, Plagerson et al. (2019) have examined the trajectory of social policy in addressing the recent social development challenges, whilst recent work carried out by Ciambotti et al. ( 2023 ) demonstrates how social enterprises in Kenya and Uganda can have a real social impact in reference to fair trade to provide sustainable and equitable trade relationships. In the case of Zambia, Chilufya et al. ( 2023 ) observe that social enterprise in the Copperbelt province region is an economic tool that is a social value creator that has greatly enhanced citizens’ employability, health, food security, and enriched support for other family members. At the epicenter of these public policy debates on social development is the agreement that, in an African context, entrepreneurship and innovation are fundamental tools that drive up economic growth and prosperity (Au et al., 2023 ; Daya, 2014 ; Littlewood & Holt, 2017 ).

3.4 Social enterprise and the SDGs

The SDGs were formulated by a UN-established Open Working Group in January 2013, which engaged various stakeholders including governments, civil society organisations, the scientific community, and representatives from the business sector. In terms of business engagement, the focus primarily revolved around large-scale business associations such as the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (Kolk, 2016 ; Littlewood & Holt, 2018 ). However, this process has been criticised for its narrow focus on multinational corporations (MNCs), its emphasis on size, and its failure to recognise the significant potential of micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in contributing to the achievement of the SDGs (Social Enterprise UK, 2015 ). Critics have also pointed out that the SDGs do not adequately acknowledge the important role that businesses – including responsible trading, social entrepreneurship, and social enterprises – need to play in their realisation (Social Enterprise UK, 2015 ).

Academic literature exploring the relationship between the SDGs and social enterprises/social entrepreneurship is still limited, given the recent introduction of the SDGs. Nevertheless, several relevant cases can be found. For example, Buzinde et al. ( 2017 ) discuss how social entrepreneurship in tourism can contribute to the achievement of the SDGs, while Sheldon et al. ( 2017 ) examine the SDGs in relation to advancing the research agenda for social entrepreneurship and tourism. Gicheru ( 2016 ) and Wanyama ( 2016 ) explore the role of cooperatives in achieving the SDGs, particularly the goal of decent work. Ramani et al. ( 2017 ) investigate the value of social entrepreneurship in attaining SDG 6, focusing on sustainable water and sanitation management, particularly in India. Finally, Rahdari et al. ( 2016 ) propose a framework for SDG achievement from a Schumpeterian perspective, highlighting social enterprises and social entrepreneurs as key actors.

Research conducted by Leagnavar et al. ( 2016 ) for Business Call to Action and the UNDP suggests that traditional businesses can contribute to the achievement of the SDGs through their core operations, philanthropy, or public-private partnerships. Social enterprises, on the other hand, have distinct ways of supporting the SDGs compared to traditional corporations. Holt and Littlewood ( 2015 ) argue that social enterprises can generate positive social and environmental impact throughout their value chains. This can be accomplished through various means, such as ethically sourcing inputs, providing goods and services that address social needs (e.g. solar lights, affordable sanitary pads), distributing revenues or surpluses to members (e.g. cooperatives), or implementing direct programmes and interventions like educational outreach or water infrastructure development. Littlewood and Holt ( 2018 ) further suggest that social enterprises can contribute to the achievement of the SDGs by creating social value along their value chains. Building upon the work of Holt and Littlewood ( 2015 ), they classify social enterprises into four basic categories: “focused contributors”, focused integrated contributors”, “wide contributors”, and “broad, integrated contributors” (see Fig. 3 ).

Social enterprises’ contribution to the SDGs.(Adapted from: Littlewood & Holt, 2018 )

Social enterprises have the potential to expand their contribution to the SDGs by developing new programmes and activities. Social entrepreneurs can opt to restructure their value chain activities to enhance their impact on the SDGs. Whether they are integrated or not, focused contributor social enterprises can exert significant influence on one or more SDGs. On the other hand, broad contributors, regardless of their nature, can only have a minimal impact on numerous SDGs. It is worth noting that social enterprises that contribute to the achievement of the SDGs can also generate substantial social benefits in areas that may not be explicitly covered by the SDGs (Littlewood & Holt, 2018 ).

4 Research methodology

This study, exploring perceptions and experiences of critical actors in the social enterprise sub-sector, employed a qualitative approach to address the key questions formulated for this investigation. Each question was constructed following the recommendations of Robson and McCartin ( 2017 ) who proposed that questions should arise from a comprehensive review of the available literature and those prevailing issues congruent with the overall aim of the research. Adopting this approach enabled a clear and accurate representation of the research problem and the development of a research strategy that responds to the how, what, and why nature of the issues presented in the study:

How do social enterprises align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations?

What are examples of social enterprises that are actively working towards achieving specific SDGs?

What ways can social enterprises contribute to the attainment of the SDGs more effectively than traditional businesses or government initiatives?

What are the challenges that social enterprises face when integrating the SDGs into their operations and strategies and how can these challenges be overcome?

How do social enterprises measure and track their impact in relation to the SDGs?

Using purposive sampling, 80 potential participants were invited to take part in this study; in total, 60 participants accepted the invitation. This sample included social entrepreneurs, and actors from industry and civil society organisations (CSOs). In total, five focus group discussions (including 60 participants) and 20 in-depth interviews were conducted with each interview and focus group discussion conducted in person and recorded by digital voice recorder. To promote transparency and contribute to credibility, as suggested by Braun and Clark ( 2006 ), an anonymous overview of the interviews and focus group participants (see Appendix 1) is provided.

Interview data was analysed using thematic analysis, a method of analysing qualitative data that involves identifying, organising, and interpreting patterns of meaning (or themes) within the data. Thematic analysis is a valuable tool that can be used to analyse data that explores people’s views, opinions, experiences, or values from data found in interview transcripts that examine how topics and concepts are constructed or represented in the data collected (Robson & McCartin, 2017 ). Whilst there are several ways of conducting thematic analysis, for the purpose of this study Braun and Clarke’s ( 2006 ) six-step process was used as it proves to be more flexible than traditional inductive or deductive strategies. This is a widely used and flexible method of thematic analysis that involves: familiarisation, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing these up. This approach can also take on an essentialist or realist perspective, aiming to report the experiences, meanings, and realities of participants. Alternatively, it can adopt a constructionist stance, which delves into the ways in which events, realities, meanings, and experiences are shaped by various discourses operating within society. This approach was therefore selected as it reflected the pragmatic social realist nature of the phenomena under investigation. Consequently, five resultant themes were derived from the data:

Nature of social enterprises in Ghana.

Where Social Enterprises Have a Big Impact – Three Examples.

Social entrepreneurship: Evaluation approaches and frameworks.

Social enterprise financing.

Social enterprise and SDGs.

5 Discussion Of findings and results

This section presents the key findings of the thematic analysis and presents the key themes and a number of sub themes arising from the data.

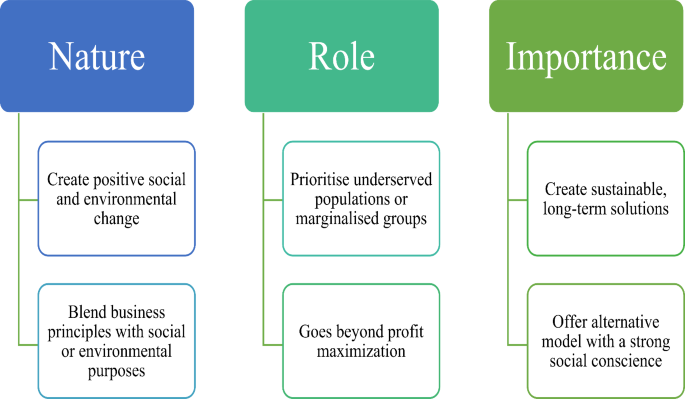

5.1 Nature of social enterprises in Ghana

Participants from both the individual interviews and focus groups provided similar insights into the nature, role, and importance of social enterprises in Ghana. In terms of their nature, 60% of participants perceived social enterprises to be organisations that pursue both social and economic objectives. These enterprises are driven by a mission to create positive social and environmental change while generating revenue through the sale of goods and services. Social enterprises were recognised for their innovative approaches to addressing social issues, blending business principles with social or environmental purposes.

Regarding their role, 80% of participants described social enterprises as entities that go beyond profit maximisation. They actively aim to tackle societal challenges such as poverty, inequality, environmental degradation, and access to education or healthcare. Social enterprises typically operate in sectors like fair trade, renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, education, healthcare, and community development. They prioritise underserved populations or marginalised groups, seeking to empower them and enhance their quality of life.

During the focus group discussion on the importance of social enterprises in addressing the global climate change problem, 60% of participants highlighted their ability to create sustainable, long-term solutions to social issues. Additionally, 50% acknowledged that social enterprises offer an alternative model that combines the benefits of traditional businesses with a strong social conscience. Furthermore, 70% emphasised the contribution of social enterprises to economic development through job creation, innovation, and the stimulation of local economies. They inspire and mobilise individuals, communities, and other businesses to engage in social change and promote responsible business practices. Figure 2 offers a snapshot of social enterprise characteristics based on the findings from the focus groups with participants. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the main themes, sub-themes, and supporting details of the social enterprise attributes in Ghana.

By acting entrepreneurially and embracing various business models, social enterprises pursue social, environmental, and inclusive objectives as their core mission while striving to generate significant revenue. These enterprises operate independently from the government and other public administrations, adopting for-profit or non-profit structures with measurable and managed impacts. They can take the form of cooperatives, mutual organisations, or charity organisations. The focus group participants agreed that social enterprises exist across various sectors of Ghana’s economy, including Climate-Smart Agribusiness, Inclusive Financial Services, Clean Technology, Health, Education, Justice, Water, and Sanitation. Of the social enterprise participants, 90% recognised a strong correlation between the outputs of social enterprises and the achievement of specific SDGs, notably Goal 1: No poverty, Goal 2: Zero Hunger, Goal 3: Good Health and Wellbeing, Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, and Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth. Participants believed that social enterprises with business models providing environmental solutions offer an effective means of attaining the SDGs.

In the focus group discussions, 70% of industry players acknowledged that social enterprises exert influence in three ways: by raising possibilities, desirability, and acceptability. They serve as sustainable business examples, inspiring other companies and introducing replicable models. Social enterprises contribute to the development of sustainable businesses, consumers, and employees by challenging what is considered socially acceptable.

Participants also mentioned the challenges faced by social entrepreneurs, including navigating regulatory landscapes and limited access to markets and consumers in Ghana, Africa, and globally. The interviews conducted during the social enterprise convention organised by STAR-Ghana Foundation in partnership with Social Enterprise Ghana provided insights from industry experts and participants. Among the participants, 90% of industry players in the social enterprise sub-sector highlighted the employment opportunities their enterprises create for young people and women, ultimately helping to reduce poverty in the communities they operate in.

Although participants provided various descriptions of social enterprises, there was a general consensus regarding their scope, nature, role and importance. In summary, this study provides a four-dimensional definition for social enterprises as shown in Table 2 .

After the four focus groups and a series of interviews, the authors’ objective was to determine where social entrepreneurs fall within the economic ecosystem and their role in the context of national development. In Fig. 4 , the sectors of the economy are categorised into two distinct classifications – Private Sector Goods and Public Sector Goods – in terms of the provision of goods and services.

Economic sectors for social enterprises

The private sector is made up of private entrepreneurs who provide goods and services to consumers with the aim of making profit. These entrepreneurs mobilise resources from both equity and debt sources to establish and sustain their businesses, aiming to yield returns sufficient to compensate equity and debtholders. The orientation reflects a pronounced profit motive, characterised by a notably aggressive pursuit for financial gains.

From insights gained through interviews and focus groups, there emerged a consensus that social entrepreneurs predominantly contribute to the provision of public goods. Participants overwhelmingly supported this perspective, citing the innovative approaches employed by most social enterprises to address complex challenges such as poverty, social exclusion, and environmental issues. These entities achieve financial sustainability through market-based revenue generation.

The question arose as to the type of public goods offered by social entrepreneurs. Public goods traditionally fall under the purview of the political class through governmental programmes, policies, and intervention. However, social enterprises play a distinctive role in providing public goods independently of government initiatives, filling the void left unattended by official programmes and policies. The unique feature of their contribution is their environmental consciousness, coupled with the sustained viability of their business operations achieved through reinvesting profit from the minimal margins charged on goods and services they offer.

Figure 4 visually depicts the strategic position of social enterprise within the economy, emphasising that public sector goods emanate from both the political class and the non-political class. Public or civil servants act in the political space, while social entrepreneurs act in the non-political space to deliver public goods.

5.2 Where social enterprises have a big impact – three examples.

5.2.1 trashy bags project.

Trashy Bags is an environmentally responsible company in Ghana that turns recycled plastic waste into attractive handbags, briefcases, backpacks, and gifts. The core of Trashy Bags’ business strategy is hiring Africans, because they believe that sustainable development, not charity, enables Africans to support themselves. Customers are urged to purchase bags and presents online to support this ethical business and the expansion of the West African economy. The business model for Trashy Bags contributes to the achievement of Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation, as their activities reduce pollution caused by plastic bags. The reduction in the volume of plastic rubbish also goes a long way toward ensuring the good health and wellbeing of the populace, consistent with Goal 3: Good Health and Wellbeing. Furthermore, their activities create ongoing youth employment opportunities, in line with Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth.

5.2.2 Strangers with hope foundation

A non-profit community-based organisation called Strangers with Hope Foundation works in Ghana’s central region to enhance civil society, health, education, and economic development in both rural and urban communities. The Strangers with Hope Foundation wants to make the general public the driving force behind growth. Through practical and comprehensive initiatives that address social and economic concerns, the foundation promotes sustainable development in partnership with local, national, and worldwide partners. In its catchment area, the foundation is fully active in 45 rural and urban areas. The organisation started its operation in the village of Aberful in 2008, with interventions on malaria, tuberculosis, family planning, maternal and child health, and subsidised agriculture extension services, all of which contribute to the achievement of Goal 3: Good Health and Wellbeing.

5.2.3 The KARIBS foundation

Based in Accra in Ghana, the KARIBS Foundation is a Pan-African development and research organisation. It is a non-profit, non-governmental, people-centered civil society organisation that focuses on five operational thematic areas: education, livelihood, protection, environment, and advocacy. The KARIBS Foundation is a legally recognised national organisation that operates all over the nation with a global satellite working team, five administrative employees, and ten regional working coordinators in each of the country’s ten regions. The foundation has previously worked on the Poverty Reduction Strategy Programs and the MDGs, and is currently working to achieve the SDGs by giving opportunities to volunteers, interns, and research workers around the globe in order to have a long-lasting impact on the lives of women, children, and young people in underserved communities.

5.3 Social entrepreneurship: evaluation approaches and frameworks

Social innovation encompasses innovative activities and services conducted by enterprises with a social aim (Halberstadt et al., 2021 ), engaging people who benefit from social good (Phillips et al., 2015 ). Social entrepreneurship is considered a catalyst for change, driving an ongoing process of innovation to tackle societal challenges (Segarra-Ona et al., 2017 ). This approach emphasises the proactive nature of social enterprises that seek rapid and effective transformations (Kuratko et al., 2017 ) and strive to become leaders in addressing specific social issues (Dees, 2012 ). During our focus group discussions, participants were asked to share thoughts on examples of social businesses in Ghana aligned with the achievement of the SDGs. Examples given were Farmerline (Goal 2: Zero Hunger and Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth), Clean Team Ghana (Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation and Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities), Solar Light for Africa (Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy and Goal 13: Climate Action), Development Action Association (DAA) (Goal 5: Gender Equality and Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth), and Trashy Bags (Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production and Goal 14: Life Below Water).

The connection between social entrepreneurship and sustainable development is often examined through the measurement of social impact (Haldar, 2019 ), using various methods and tools (Kraus et al., 2017 ). The Social Return on Investment model calculates the ratio between the enterprise’s return on investment and the value of its initiatives in promoting social good (Moody et al., 2015 ; Walk et al., 2015 ). Other models focus on costs, such as cost-benefit analysis, cost-effective analysis, and cost per impact analysis. The Balanced Scorecard approach assesses enterprises from different perspectives (mission and vision, financial, stakeholder management, internal organisation, etc.) to determine their operational effectiveness (Kaplan & Norton, 1996 ). Later, the Social Enterprise Balanced Scorecard was developed to align with the aims and achievements of social enterprises (Kaplan & Norton, 2001 ).

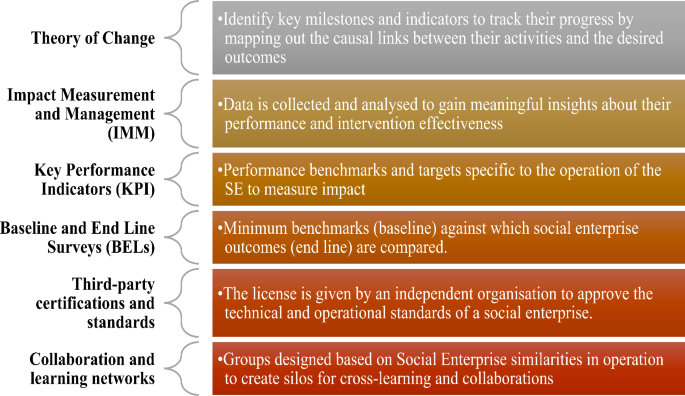

In light of this, focus group participants were tasked to brainstorm ideas on how social enterprises measure and track their impact in relation to the SDGs and whether there are any established frameworks or methodologies these social enterprises can use for evaluation. After brainstorming ideas, participants in Tamale in the northern region of Ghana cited Theory of Change (ToC) and Impact Measurement and Management (IMM) frameworks as approaches social enterprises use for evaluation. Participants explained that ToC can help social enterprises articulate their long-term goals and the pathways to achieve those goals. By mapping out the causal links between their activities and the desired outcomes, social enterprises can identify the key milestones and indicators to track their progress and measure their impact. In terms of the IMM framework, participants noted that social enterprises can collect relevant data, analyse it, and derive meaningful insights about their performance and the effectiveness of their interventions. Participants further shared their views on how IMM frameworks allow social enterprises to go beyond just measuring outputs and activities; they help them to understand the broader outcomes and impacts they are making on individuals, communities, and the environment. By adopting these frameworks, social enterprises can continuously improve their strategies and programmes based on evidence-based insights. Table 3 presents participant viewpoints on entrepreneurship and innovation as an evaluation framework.

Participants in Accra used examples to explain how some social enterprises in Ghana adopt the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and Baseline and End Line Surveys (BELs) to measure their impact (see Fig. 5 ). Focus group one reflected as follows:

“One example is the social enterprise called Farmerline. They use KPIs to measure their impact on smallholder farmers in rural areas. Their KPIs include the number of farmers reached with their agricultural advisory services , the increase in farmers’ crop yields , and the improvement in farmers’ income levels”. “Another social enterprise that utilises KPIs is Clean Team Ghana. They provide sanitation solutions in low-income communities. Their KPIs include the number of households with access to clean toilets , the reduction in waterborne diseases , and the improvement in overall community hygiene. These indicators enable Clean Team Ghana to evaluate their impact and make data-driven decisions”.

Social enterprise evaluation models from the key findings

Ashesi University Foundation, a social enterprise working in the education sector, conducts BELS to assess the impact of their scholarship programmes on students’ educational outcomes. These surveys capture data on enrollment rates, academic performance, and career progression. By comparing the baseline and end-line data, Ashesi University Foundation can measure the effectiveness of their scholarships in improving access to quality education (Focus Group 2).

Finally, the focus group discussions held in Koforidua saw participants contributing in diverse ways. Similar to earlier focus groups, the Koforidua focus group also engaged participants to share ideas on how social enterprises in Ghana can evaluate their impact. The group came up with two frameworks: (1) Third-party certifications and standards and (2) Collaboration and learning networks (see Fig. 5 ). Participants cited Fairtrade Africa and Global Mamas as social enterprises that use this methodology for evaluation. Fairtrade Africa is a social enterprise that promotes fair trade practices in agriculture by adhering to the Fairtrade Certification, which guarantees that their products meet social, economic, and environmental standards. This certification not only validates their commitment to ethical practices but also serves as a tool for evaluation and transparency (Focus Group Discussion 1). Another example is Global Mamas, a social enterprise that empowers women artisans. They have obtained various certifications, such as the World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO) certification and the B Corporation certification. These certifications provide credibility and assurance to customers while also serving as evaluation mechanisms for the social and environmental impact of their operations.

5.4 The state of social enterprise in Ghana

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) recognise and prioritise the domestic resources of organisations as a tool and strategy for the sustainable financing of development. They also prioritise the private sector as a critical actor and contributor to social and economic development financing. The focus groups helped the researchers to define social enterprises as businesses that contribute to addressing social problems through funding or resourcing from their profits. In collaboration with Social Enterprise Ghana, the British Council, and USAG, the Ministry of Trade and Industry have developed a social enterprise policy for Ghana to provide an administrative, regulatory, and institutional framework for social enterprise in Ghana. This policy is still in draft.

Fighting poverty and inequality and promoting good governance have been tasks primarily linked to social enterprises. Funding for social enterprises has traditionally come from donors. The Ghana Beyond Aid Policy Document notes the waning of aid and recognises sectors like health and education as the highest aid beneficiary. The changes in the external environment, especially throughout COVID-19, have impacted funding. Furthermore, the changing priorities of donors and what they choose to invest their money in, and the geographic and thematic areas they prioritise, have also impacted funding. This has resulted in the overall reduction of funding. Nevertheless, social enterprise has been identified as a sustainable tool and strategy in fighting poverty and exclusion.

Young people and women heavily dominate social enterprises in Ghana where they are more prevalent than in other sectors. Young people between the ages of 25 and 34 create Ghanaian social enterprises; these are usually individual social enterprises set up by graduates or people who are unemployed or unhappy with their roles, or those seeking something they are passionate about. Smaller and eco based social enterprises are dominated by women entrepreneurs and frequently encounter challenges in terms of equity of space and reach. Social enterprise in Ghana is a sub-sector of the Micro and Small-Medium Scale Enterprise (MSME) sector and covers many more start-ups and micro and small-medium scale businesses that might not necessarily be for social growth. The social enterprise sub-sector covers businesses set up to solve social problems. The core vision of the social enterprise sub-sector in Ghana is to solve social problems and use social enterprises as the vehicle for achieving the SDGs.

5.5 Social enterprise financing

Sustainable financing is critical in the realisation of the SDGs. Continuously aligning global goals to the national budget and interlocking innovation, social entrepreneurship, private enterprise, and research will help bridge the financing gap. At present the private sector provides support for social enterprises through their corporate social responsibility, but the benefit of corporate philanthropy still remains unutilised. Corporate philanthropies possess the capacity to provide finance for national and community level projects relieving pressure off the shoulders of the central government. Some SDG philanthropies have created platforms for optimising funding support by leveraging wider participation like crowdfunding, online funding and venture philanthropy for most social enterprises.

Ghanaian CSOs have recently used social enterprise and social impact investments as a financial diversification strategy due to the decline in donor inflows (Arhin et al., 2018 ). While the growth of social enterprises in Ghana is still in its infancy, impact investing, which involves making financial investments with the intention of enhancing social and environmental conditions, is gaining popularity. In Ghana, 32 active impact investors made direct investments totalling over US$1.7 billion between 2005 and 2015, while another US$430 million was pledged indirectly through funds and intermediaries, according to the Global Impact Investment Network (2015, p. 9). Indeed, as Hailey and Salway ( 2016 ) argue, the growth of impact investment is aided by innovative crowd-funding platforms and peer-to-peer lending. Impact investing is exemplified by The Acumen Fund, which uses its charitable funds to launch social entrepreneurs in Ghana. For instance, The Acumen Fund contributed US$1 million to Medeem Ghana Limited in 2011 (Acumen, 2012 ). Two more are the Venture Capital Trust Fund, established in 2004 to provide investment for small and medium-sized firms, and Slice Buz, a diaspora fund that invests in Ghanaian start-ups.

Social enterprises serve as prime examples of a hybrid philanthropy model because they are driven by the desire for self-help and mutual aid and hence depend on funding from external donors as well as community support to function. However, a number of NGO employees voiced concern that the absence of a regulatory and legal framework would cause investors to become financially driven at the expense of their humanitarian and environmental objectives. Conversely, some interviewees asserted the following:

“NGOs that participate in the social enterprise will have no impact on our advocacy and service delivery duties. We’ll find a balance by focusing on those living in poverty so that our social venture doesn’t become overly profit-driven.” (STAR-Ghana Foundation staff, 25th January 2022).

The study’s conclusions support the UNDP’s ( 2017 ) claim that Ghana has a social business policy, though it is still in the draft stage. Despite the existence of a draft policy, according to Social Enterprise Ghana authorities, it has not yet been put into effect. This contradicts the conclusions of Darko and Koranteng ( 2015 ), who found that Ghana lacks strong social business policies, which has made it difficult to build the foundation and provide incentives for impact investing.

5.6 Social enterprise and SDGs

During our focus group discussions, participants shared their insights on how social enterprises can contribute to the attainment of the SDGs more effectively, compared to traditional businesses or government initiatives. The key points raised, along with the percentage of participants who supported each suggestion, were as follows:

Mission-driven approach: 85% of participants emphasised the importance of social enterprises’ mission-driven approach. They highlighted that social enterprises have a clear purpose to address social and environmental challenges, making them more focused and committed to achieving the SDGs.

Innovative and adaptive solutions: 90% of participants acknowledged the innovative and adaptive nature of social enterprises. They appreciated how social enterprises continuously seek new and creative solutions to complex societal problems, adapting to changing circumstances and finding unconventional approaches to tackle the SDGs.

Empowerment and inclusion: 80% of participants recognised the role of social enterprises in empowering and including marginalised communities. They noted that social enterprises prioritise providing opportunities for skills development, training, and employment, enabling individuals and communities to actively contribute to the SDGs and improve their quality of life.

Leveraging market mechanisms: 75% of participants emphasised the importance of social enterprises leveraging market mechanisms. They highlighted how social enterprises create sustainable business models that generate revenue while addressing social and environmental challenges, reducing their dependence on external funding sources and enabling long-term impact.