Brisbane man missing after falling overboard from Quantum of the Seas cruise ship near Hawaii, US Coast Guard confirms

The US Coast Guard said it will resume its search at first light on Friday morning local time, for a Brisbane man who went overboard from a cruise ship off Hawaii on Wednesday night.

Key points:

- Life rings, search vessels, and lights were used overnight to try to locate the missing man

- A fellow passenger described the ordeal as "very traumatic and sad"

- Royal Caribbean staff have been described as "amazing" throughout the process

The ship, the Royal Caribbean's Quantum of the Seas, halted its course after the incident, which took place about 500 nautical miles south of Hawaii's Big Island, and took part in the initial search for about two hours.

The cruise ship has since continued its course.

Aimee West, from Mount Isa, and her partner were on the cruise.

"There was a lot of commotion on the boat. It all started at about 9pm," she told ABC North West.

"There were a few medical emergencies so the loudspeaker was going off quite a lot.

"At about 11pm, midnight, we observed the vessel slowing down and turning around on our maps.

"We saw about five life rings that were floating in the ocean and there were search vessels and lots of lights on the water.

"They broadcast several times that there was a suspected man overboard situation and that the crews were following their procedures.

"They requested all guests return to their cabins and account for all their members and if someone was missing, to call 911 on our emergency systems here if we were missing a passenger.

"We were messaging our friends to make sure they had everyone in their party.

"To be real, for me personally it was very surreal and quite sad. It was quite confronting, we were all out trying to spot anything to help the staff.

"But it was very sad going to bed, that's for sure."

The mood on the ship was quite sombre, Ms West said.

"You can tell the crew is trying to do their best to keep spirits up for everyone else on board for the rest of their trip.

"Everyone kind of realises it's very traumatic and sad and you feel for the families involved.

"We were awake until about 1.30am and they were still searching."

Brad Hardy, from Mount Isa, said he was on deck 14 of the cruise ship when he heard the emergency broadcast.

"All the staff just dropped everything and ran to every possible vantage point on the ship," Mr Hardy said.

"We looked out of the window up on the deck and [saw] a lot of life preservers … the big rings were getting thrown overboard, at least eight or nine of those got thrown overboard.

"The ship slowed right down and then did a hard turn to the left and doubled back.

"The search lights were on from the ship's bridge as well, they rapidly deployed their 'runabout' rescue vessel off the ship and then spent the next couple of hours in the water searching around.

"Probably around 1am we started moving again.

Gayle Doe, from New South Wales, is also on board and described the ordeal as "scary and unsettling".

"We were sitting at the bar at 11 o'clock last night when we heard 'Oscar, Oscar, Oscar' which is the code for man overboard," Ms Doe said.

"There were a lot of announcements, telling us that the ship was being turned around, most people could feel the ship had changed course, it was a bit bumpy in the water.

"The crew went into their training mode, they threw lifebuoys out into the sea and they deployed their … lifesaving boats.

"Of course, it was night-time – it was black, so they had lots of spotlights on the ocean … but weren't successful [in finding the man].

"We've been told the coast guard and helicopters are still out searching in the ocean, in the area where the man went."

She said there was "a lot of sadness" on board the ship on Thursday.

"There are people who have been crying," Ms Doe said.

She said the cruise ship captain had been providing regular updates over the loudspeaker and had just confirmed there would be no further updates.

Cruise staff 'amazing'

Ms West said the Royal Caribbean cruise staff "were amazing" and have kept all passengers updated throughout the ordeal.

"We even witnessed staff when, we were in Tahiti [earlier], practising retrievals in the water," she said.

"The staff were all out on safety posts, there was not a space or inch on the boat where there wasn't a staff member shining a torch in the water."

The Honolulu Command Centre has confirmed that the person missing is an Australian man, but provided no further details.

A Royal Caribbean Cruise Line spokesperson confirmed the Quantum of the Seas departed Brisbane on April 12 and is scheduled to arrive in Honolulu on April 28.

"While on its trans-Pacific sailing, a guest onboard Quantum of the Seas went overboard," the spokesperson said.

"The ship's crew immediately launched a search and rescue operation and is working closely with local authorities."

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Disasters, Accidents and Emergency Incidents

- Maritime Accidents and Incidents

- Missing Person

- Travel Health and Safety

- Travel and Tourism (Lifestyle and Leisure)

- United States

Local news:

Sign up to the 7NEWS newsletters

Australian cruise passenger dies while swimming on mystery island.

Cruise ship returns after passenger's death

A Carnival cruise passenger who died while swimming in Vanuatu was an Australian, it has been revealed.

The passenger died on Mystery Island on May 20, Carnival Australia confirmed to 7NEWS.com.au.

WATCH THE VIDEO ABOVE: Cruise ship returns after passenger’s death.

“Carnival Cruise Line is deeply saddened by the death of a guest on Mystery Island, following what appears to be a medical situation while swimming,” it said.

“Our Care Team are supporting the guest’s family along with other guests during this difficult time.”

A passenger on board told 7NEWS the passenger died while snorkelling.

The Carnival Splendour cruise ship departed Sydney on Monday, May 15 on a 9-day route across the South Pacific.

It arrived back in Sydney on Wednesday morning.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade told 7NEWS.com.au it is “providing consular assistance to the family of an Australian who died in Vanuatu”.

“We offer our deepest condolences to their family and friends,” it said.

New York City is sinking.

Stream free on

- SYDNEY, NSW

- MELBOURNE, VIC

- HOBART, TAS

- BRISBANE, QLD

- ADELAIDE, SA

- CANBERRA, ACT

- Seven youths arrested in Sydney amid terror investigation

Passenger on Australian cruise ship dies while swimming in Vanuatu

Send your stories to [email protected]

Auto news: $400k luxury car recall with 'risk of an accident causing death'.

Top Stories

Seven youths arrested in counter-terrorism raids across south-west Sydney

TODAY IN HISTORY: 'Monsters are real': the cop turned serial killer

The moment that cemented Hill as a cult hero

Family of missing Australian earthquake victims call for rescuers to remain safe

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Carnival Was Negligent in Covid Outbreak on Cruise Ship, Court Rules

An Australian judge found that the cruise company and a subsidiary “breached their duty of care” in handling a coronavirus outbreak on the Ruby Princess in March 2020.

By Michael Levenson

The coronavirus was already devastating parts of the world, bringing illness and death, and the future was uncertain when Henry Karpik, a retired police officer from the Australian suburb of Figtree, and his wife of nearly 50 years, Susan Karpik, began their holiday cruise to New Zealand aboard the Ruby Princess.

It was March 8, 2020. About a week earlier, a passenger on another cruise ship, the Diamond Princess , had become the first Australian to die of Covid-19.

A few days after the Ruby Princess left Sydney, Australia, Mr. Karpik began to feel tired, weak and achy, court records show. By the time the ship returned to Sydney, on March 19, 2020, Ms. Karpik saw that her husband was shaking and barely able to walk or carry his luggage, according to court documents.

Mr. Karpik, who was 72 at the time, spent nearly two months in the hospital, was placed on a ventilator, put into an induced coma and, at one point, given only a few days to live, court records show. He later recovered.

Ms. Karpik, the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit against the cruise company Carnival, which chartered the Ruby Princess, also contracted Covid-19, although her symptoms were milder.

On Wednesday, an Australian court found that Carnival and a subsidiary, Princess Cruise Lines, were negligent and had “breached their duty of care” in their handling of a coronavirus outbreak aboard the ship in the early days of the pandemic.

About 2,670 passengers and 1,146 crew members were aboard the Ruby Princess. About 660 people on board contracted coronavirus, and 28 died, according to court records.

Ms. Karpik, a retired nurse, had sought damages for “personal injuries and distress and disappointment” of more than 360,000 Australian dollars, or about $227,000.

But Justice Angus Stewart of the Federal Court of Australia found that Ms. Karpik’s Covid-19 infection gave rise to “very mild symptoms,” and did not result in long Covid. He awarded her 4,423 Australian dollars, plus interest, or about $2,790, for her out-of-pocket medical expenses.

“I have found that before the embarkation of passengers on the Ruby Princess for the cruise in question, the respondents knew or ought to have known about the heightened risk of coronavirus infection on the vessel, and its potentially lethal consequences, and that their procedures for screening passengers and crew members for the virus were unlikely to screen-out all infectious individuals,” Justice Stewart wrote .

Justice Stewart ruled that Carnival knew of the danger to passengers from outbreaks in February 2020 on other vessels owned and operated by the company, namely the Diamond Princess off Japan and the Grand Princess off California.

“To proceed with the cruise carried a significant risk of a coronavirus outbreak with possible disastrous consequences, yet they proceeded regardless,” Justice Stewart wrote.

Vicky Antzoulatos, Ms. Karpik’s lawyer, said that each passenger would need to prove individual damages unless Carnival settles the lawsuit. All of the passengers who were on the ship are part of the class action, she said.

“Susan’s husband was very catastrophically injured, so we expect that he will have a substantial claim, and that will be the same for a number of the passengers on the ship,” Ms. Antzoulatos said, according to The Associated Press .

Carnival Australia said in a statement: “We have seen the judgment and are considering it in detail. The pandemic was a difficult time in Australia’s history, and we understand how heartbreaking it was for those affected.”

Ms. Karpik said that she was pleased with the judgment and that she hoped it would help other passengers on the Ruby Princess and the families of those who died.

“I hope the finding brings some comfort to them,” she told reporters, according to 9News , “because they’ve all been through the mill and back.”

Michael Levenson joined The Times in December 2019. He was previously a reporter at The Boston Globe, where he covered local, state and national politics and news. More about Michael Levenson

Come Sail Away

Love them or hate them, cruises can provide a unique perspective on travel..

Cruise Ship Surprises: Here are five unexpected features on ships , some of which you hopefully won’t discover on your own.

Icon of the Seas: Our reporter joined thousands of passengers on the inaugural sailing of Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas . The most surprising thing she found? Some actual peace and quiet .

Th ree-Year Cruise, Unraveled: The Life at Sea cruise was supposed to be the ultimate bucket-list experience : 382 port calls over 1,095 days. Here’s why those who signed up are seeking fraud charges instead.

TikTok’s Favorite New ‘Reality Show’: People on social media have turned the unwitting passengers of a nine-month world cruise into “cast members” overnight.

Dipping Their Toes: Younger generations of travelers are venturing onto ships for the first time . Many are saving money.

Cult Cruisers: These devoted cruise fanatics, most of them retirees, have one main goal: to almost never touch dry land .

- Travel Updates

Cruise passengers reject ‘unacceptable’ compensation after ‘cruise from hell’

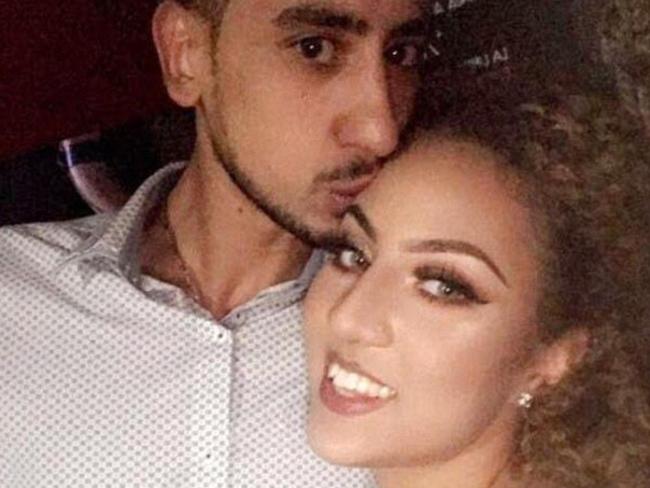

MICHAEL was in the middle of proposing to his girlfriend when all hell broke loose on the Carnival Legend cruise ship.

Disaster at JFK Airport narrowly avoided

‘Taking a dump’: Aussie hidden gem ruined

Horror ‘infection’ leaves woman paralysed

IT WAS meant to be a special moment for this couple, but now it will be one they will never forget - for all the wrong reasons.

In the perfect setting while on a 10-day cruise holiday in the South Pacific, Michael Barsoum was to propose to his partner Mary.

Unfortunately for the pair, it ended up being horrible timing, as it was also the moment when chaos erupted on the cruise ship the Carnival Legend.

Passengers on the ship, which arrived in its home port in Melbourne yesterday, endured three days of violence before a 23-member family was offloaded in an unscheduled stop-off on the NSW South Coast.

“That moment is ruined forever now,’ Mr Barsoum told the Herald Sun of his proposal.

Mr Barsoum, from Cranbourne in Melbourne, said he was forced to halt the proposal to help innocent passengers who were being caught up in the bloodshed.

“Women and children were getting pulled into the fights ... I was punched in the face trying to protect my fiance.”

He is among hundreds now demanding a refund for the “cruise from hell”.

“I want my money back. I want a complete refund,” he said.

‘INSULT TO INJURY’ AFTER CRUISE HELL

“We just disembarked from Carnival Legend in Melbourne. It was the holiday from hell. I would never travel with Carnival again,” Bec Dunn posted on the cruise line’s Facebook page.

Yesterday witnesses said a large family had “picked on Aussies” and “strangled and punched” passengers for three days before Carnival Legend called police and offloaded the relatives.

A bloody clash at 1:30am on Friday forced Carnival to the “unprecedented” eviction of the 26-member family, after calling NSW Police and docking at Eden on the NSW South Coast.

Video footage taken by some passengers on the 10-day South Pacific cruise shows skirmishes on the pool deck in broad daylight in the days leading up to the final, bloody conflict. Video shows young adults fighting with ship’s pursers and other staff on deck.

Women and men push and shove with the Carnival Legend officers dressed in white uniforms.

NSW Police said six men and three teenage boys were removed from the ship at Twofold Bay in Eden. A further 14 passengers, including women and children, then also voluntarily left the ship. No one has been charged following the incident.

As the family was offloaded on to police boats on Friday morning, passengers rained down a barrage of insults from above on deck, yelling “Get off” and “You’re not heroes, you’re deros”.

One of the evicted members of the family held up a derisive finger in response.

The cruise company’s executives later confirmed that one family had been involved in ongoing incidents.

‘I WON’T BE TRAVELLING WITH THEM AGAIN’

In a statement today Carnival Cruise Line announced guests will be offered a 25 per cent Future Cruise Credit as “a goodwill gesture”.

“We sincerely regret that the unruly conduct and actions of the passengers removed from the ship in Eden may have prevented other guests from fully enjoying their cruise on Carnival Legend,” said Jennifer Vandekreeke Vice President Australia Carnival Cruise Line.

Carnival Cruise Line said it was conducting “a full investigation to ensure that a situation such as this never happens again”.

But some passengers slammed the offer as “unacceptable”, AAP reports.

“I won’t be travelling Carnival ever again so a 25 per cent off a future cruise in my eyes is unacceptable,” Mark Morrison said.

“To add insult to injury ... they charged us a $19.54 credit card convenience fee to settle accounts before disembarkation this morning.”

Both Carnival and NSW Police are investigating the incident. In a statement, the cruise line said: “We sincerely apologise to our guests who were impacted by the disruptive behaviour of the group removed from the ship by the NSW Police in Eden.”

FATHER SLAMS CARNIVAL COMMENTS

A distressed father, which had more than 20 members on-board, has broken his silence to slam Carnival Cruise Line.

David Barkho, who was not on the cruise, reacted angrily on Facebook to Carnival’s handling of the situation.

Mr Barkho told news.com.au that he would be seeing his lawyer on Monday about the allegations. “It is in the hands of my lawyer,” he said.

Mr Barkho refused to comment on allegations made by other passengers.

On Facebook, he posted comments about a Carnival Cruise executive’s media conference, describing it as “lots of bulls**t”.

Mr Barkho had earlier told Melbourne radio station 3AW he got a 1am call from his 20-year-old son, saying he had been injured and needed help.

“He said, ‘Please, Dad, please, call the Federal Police’,” Mr Barkho said.

“I could hear a lot of screaming, crying in the background.”

Mr Barkho said George had seen “a lot of people bleeding, a lot of people down on the ground”. A photo supplied to the radio station showed George being treated for an apparent cut on his head.

There is no suggestion George Barkho was violent or engaged in any fighting.

Mr Barkho also claimed security staff deleted images of the violence from George’s phone.

PASSENGERS DESCRIBE CRUISE SHIP ‘BLOODBATH’

Passenger Lisa Bolitho told AAP there has been “very violent ... full-on attacks” before the late night “bloodbath” which saw a group of passengers evicted off the ship on Friday morning.

Ms Bolitho said she and others had “all made several complaints saying kids were scared. “They saw people getting strangled and punched up,” she said.

Ms Bolitho’s son Jarrah was targeted by the family, and had to flee with his mother, the pair locking themselves in their cabin. “I was watching the fight and one guy came up to me and said, ‘Do you want to go too, bro?’” Mr Bolitho said. “My mum had to drag me away from it all. They were trying to pick on any Aussie they could find.”

Ms Bolitho was critical of how the ship’s management handled the family, saying the captain told concerned passengers, “What do you want me to do about it — throw them overboard?”

“We were saying, ‘We want them either locked up or taken off board’,” Ms Bolitho said. “It never happened and there was another four occasions. We dropped them off at Eden yesterday, but that was after three days of violence,” Ms Bolitho said on Saturday.

She said security staff ended up “jumping” the family, and had no choice but to do so. “They deserved everything they got — they were the aggressors,” she said.

The days of fighting on board revealed in videos and passenger accounts, include guests saying they were “scared for their safety” in the eight days leading up to the family’s eviction.

Passenger Naomi told the Herald Sun that said there had been a number of fights on board, including in a nightclub and in an elevator the next day.

“And a big fight on the lido deck, which went on for about 45 minutes,” she said.

“They were loud, alcohol affected and things like that. Last night they attacked one of the security guards.

“Lots of yelling people being threatened. Being called dogs in the smoking area. A pool was full of children, people were pulling their children out of the pool because they were crying and scared.

Passenger Kellie Petersen, who was on the cruise with her husband and their three children, aged 11, 9 and 6, said trouble on board had been “brewing for days”.

“They were looking for trouble from the minute they got on the ship,” she told 3AW.

“My husband said to take it away, because there’s kids here, and five of them surrounded my husband. They told us to watch our backs.”

TROUBLE ON-BOARD BEGAN OVER A THONG

Authorities were told a “fight involving several men took place on board the ship after an argument” in the early hours of Friday morning.

“Security intervened and detained the men before notifying the Marine Area Command,” NSW Police said.

After speaking to passengers and crew for several hours, police removed the extended family. Carnival Cruise Line Australia vice-president Jennifer Vandekreeke said the incident was a first for the company and they had contacted police to meet the ship.

“Disembarking a family from a cruise is an unprecedented incident — it is always our last resort,” she said.

One member of the family known as Zac, told 3AW Radio he had been locked in his room overnight before being removed. He said the trouble started with another group over a thong and his family were being unfairly targeted.

“This is all over a thong, not a foot, a thong being stepped on and being instantly apologised for,” he said.

The Herald Sun reported members of a family had been put under “house arrest” on the ship by security guards.

Passengers described how they locked themselves in their cabins as violence between two large groups broke out on several occasions. They said threats had been made to stab and throw people overboard during what was described as a “cruise from hell”.

“We are so scared after witnessing a traumatic experience with yet again the same offenders. It was a bloodbath,” the passenger told Nine News .

“We will not be leaving our cabins and are truly scared for our safety and what could happen in the next 24 hours.”

In a statement to news.com.au, the Carnival Cruise Line said staff had taken action against a small number of “disruptive guests”.

“Safety is the number one priority for Carnival Cruise Line, we take a zero tolerance approach to excessive behaviour that affects other guests and we have acted accordingly on Carnival Legend,” a spokesman said.

“The ship’s highly trained security staff have taken strong action in relation to a small group of disruptive guests who have been involved in altercations on board.

“The ship’s security team is applying our zero tolerance policy in the interests of the safety and comfort of other guests.

“Carnival Legend is currently on a 10-day South Pacific cruise scheduled to be completed in Melbourne where the ship is currently homeported.”

A communications error nearly led to a catastrophic incident involving four aeroplanes at JFK Airport in New York.

One visitor recalled the moment they saw a fellow tourist “taking a dump” at the popular hotspot all because it’s lacking one thing.

A 23-year-old woman has been left paralysed and fighting for life after a horror infection.

- Sustainability

- Latest News

- News Reports

- Documentaries & Shows

- TV Schedule

- CNA938 Live

- Radio Schedule

- Singapore Parliament

- Mental Health

- Interactives

- Entertainment

- Style & Beauty

- Experiences

- Remarkable Living

- Send us a news tip

- Events & Partnerships

- Business Blueprint

- Health Matters

- The Asian Traveller

Trending Topics

Follow our news, recent searches, woman dies in australia after falling from cruise ship, advertisement.

A file photo showing the Pacific Explorer cruise ship. (Photo: Facebook/P&O Cruises Australia)

ADELAIDE: The body of a 23-year-old woman was found on Wednesday (Dec 14) in the ocean off Australia after she fell overboard from a cruise ship.

Crew members aboard the Pacific Explorer reported the passenger missing at about midnight, when the ship was around 70km out to sea from Cape Jaffa in South Australia state.

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority then launched a rescue plane overnight that was joined by two helicopters at daybreak. Searchers said they found the unnamed woman's body in the water just before 7am.

The cruise ship, which can accommodate about 2,000 guests, left Melbourne on Tuesday bound for Kangaroo Island in South Australia on a four-night return voyage.

Cruise ship company Carnival Australia said it was a tragic outcome.

“We continue to provide care and assistance to the family member this guest was travelling with and extend our deepest condolences to their loved ones,” the company said in a statement.

Carnival Australia said the death also “deeply impacted” other guests and the crew.

“We thank all involved who supported this distressing and challenging search operation,” the company said.

South Australia police said the ship's intended visit to Kangaroo Island was canceled and that Victoria Police would conduct an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death.

Weather conditions overnight were “extremely poor” with strong winds and big seas, Dan Gillis, a duty manager with the safety authority, told the Australian Broadcasting Corp.

Gillis said the woman's body was taken to Adelaide by helicopter, after it had earlier been taken to a nearby hospital for identification.

Related Topics

Also worth reading, this browser is no longer supported.

We know it's a hassle to switch browsers but we want your experience with CNA to be fast, secure and the best it can possibly be.

To continue, upgrade to a supported browser or, for the finest experience, download the mobile app.

Upgraded but still having issues? Contact us

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Covid outbreak on one of first cruise ships allowed to return to Western Australia

WA Health confirms it is managing positive cases onboard the Coral Discoverer, docked at Broome

- Follow our Covid live blog for the latest updates

- Get our free news app ; get our morning email briefing

Western Australian authorities are working to contain a Covid-19 outbreak onboard one of the first cruise ships allowed back in the state .

WA Health has confirmed it is managing an undisclosed number of positive cases on the Coral Discoverer, docked at Broome in the state’s north-west.

Infected passengers and close contacts are isolating and all passengers and crew are being tested.

Small cruise ships carrying no more than 350 passengers and crew have been permitted to enter WA waters since 17 April.

The Coral Discoverer, which departed from Darwin this month, has a capacity of 72 passengers.

Sign up to receive an email with the top stories from Guardian Australia every morning

“Maritime vessels are permitted to allow positive cases to disembark and move to suitable accommodation to complete their isolation/quarantine requirements,” a WA Health spokesperson said. “All precautions will be taken to ensure the Broome community is protected.”

The ship’s operator, Coral Expeditions, has been contacted for comment.

On Monday WA Health reported 5,639 Covid-19 cases and the death of a man in his 80s. There are 240 Covid patients in hospital, including nine in intensive care.

- Western Australia

- Coronavirus

Most viewed

Passenger dies aboard 9-month Royal Caribbean cruise around the world

A guest aboard a nine-month Royal Caribbean cruise around the globe has died, the company said Tuesday.

"A guest sailing on board Serenade of the Seas has sadly passed away," a Royal Caribbean spokesperson said in a statement.

Details about the passenger and the circumstances of the death were not disclosed.

"We are actively providing support and assistance to the guest's loved ones at this time. Out of the privacy of the guest and their family, we have nothing further to share at this time," the spokesperson said.

Serenade of the Seas took off from Miami on Dec. 10 on the Ultimate World Cruise voyage.

The trip takes passengers across the seas over 274 nights to all seven continents, over 60 countries and 11 world wonders, including the Taj Mahal in India and the Christ the Redeemer statue in Brazil.

The ship crossed through Mexico, the Caribbean, Brazil, Peru and Ecuador on its South America leg in January. On Sunday, the Asia Pacific leg of the voyage began; the ship will pass through Hawaii, Polynesia and Australia. From there, it will continue to other major destinations, including South Korea, Japan, India, the United Arab Emirates and Greece.

Serenade of the Seas boasts 13 decks and 1,073 guest rooms, and it can accommodate over 2,100 guests.

The Ultimate World Cruise has piqued the interest of a corner of TikTok , with some users comparing the voyage to a reality TV show experience. Users have pointed out that with so much time at sea, much can happen, including relationships, fights, pregnancy and deaths.

Several passengers on board have been consistently documenting the journey on TikTok, sharing a peek into life at sea.

One creator went so far as to make an "Ultimate World Cruise Bingo card" predicting events that could unfold, including "minor mystery to solve," "stowaway," "2nd COVID outbreak" and "staff dates passenger."

Breaking News Reporter

When a Passenger Dies at Sea: What You Need to Know

People die every day, even on vacation, even on a cruise. Sadly, this happens more often than one might think. According to the Broward County Medical Examiner's Office, which is where any deaths on cruise ships that stop at Fort Lauderdale's Port Everglades must be reported, some 91 people have died on cruise ships that arrived in Fort Lauderdale between 2014 and 2017.

While no cruise line would give Cruise Critic an exact number of deaths per year, one cruise line insider who asked to remain anonymous said, up to three people die per week on cruises worldwide, particularly on lines that typically carry older passengers.

The vast majority of deaths on cruise ships are natural, with most the result of heart attacks. But even when death is not entirely unexpected, such as when someone with advanced-staged cancer chooses to cruise, it's shocking to family and friends, whether they're on the cruise ship or on land.

But what happens when a passenger passes away while at sea or in a foreign port? What happens to the person's body? And what do that passenger's family or friends have to do? Here, we take a closer look.

How Do Cruise Lines Help Family and Friends?

It is impossible for a person to be prepared for a loved one's death but the cruise lines are, and they're quick to step in to help.

"Our crew is proactive," says a spokesperson for Carnival Cruise Line. The line has procedures in place for dealing with these situations, including employees specifically trained to provide emotional and logistical support to grieving loved ones.

Irrespective of cruise line, when a passenger dies on a cruise ship, someone from the company's Guest Care Team is immediately assigned to help the deceased's family and friends.

"Care Team members are trained to deal with grieving people, but they are not grief counselors," the Carnival spokesperson said. "They are trained to help deal with the details of repatriating a body and contact[ing] a funeral home." In addition to helping friends and families work with local authorities, make travel arrangements and deal with insurance, Care Team members will provide free Internet and phone use onboard. They'll drive the deceased person's travel companions to a hotel if they choose to disembark the ship and even stay with them until they can return home. They also do post-cruise follow-up.

How Do You Get Your Loved One Home?

The biggest concern many loved ones face is how to bring the body home from the ship for burial. Whether the body must be immediately repatriated from a foreign port or can stay onboard depends on a number of factors, including where the ship is at the time, which ports it's visiting and what the Flag State of the ship is (i.e., where the ship is registered).

According to the Cruise Lines International Association, the latter two can have requirements that necessitate the off-loading of anyone who's died, or preclude the line from being able to offload a body. Additionally, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention requires that any ship that calls or homeports at a U.S port must immediately report any deaths onboard.

Bodies can be stored in shipboard morgues as needed, though not for much longer than a week. Each oceangoing cruise ship is required to carry body bags and maintain a morgue. Separate from food storage areas, most morgues are small, with room for three to six bodies.

On standard Caribbean sailings, remains are often kept in the cruise ship morgue until the vessel returns to the United States, where a death certificate can be issued by the local medical examiner's office. However, as stated above, port authorities in any of the ports visited by the cruise have the right to require an examination of anyone who's died, as well as the off-loading of the body.

But when the ship is far from its homeport or doesn't have a homeport, the body must be repatriated from somewhere.

It's not always easy. When someone dies on a South Pacific sailing, his body will most likely remain in the ship's morgue until the ship returns to a more major port, as few, if any, of the islands on such an itinerary are equipped to handle repatriation. Likewise, authorities in many small African and Asian ports with third-world infrastructures will often refuse to allow human remains off the ship. However, alternatives can be found, if necessary, such as when a ship won't be visiting a larger port anytime soon.

For example, after a Paul Gauguin passenger died on a small island in the South Pacific, the body was first brought back to the ship but then transported to a local hospital in Raiatea where it was stored until it could be sent to Papeete, Tahiti. From there, the family of the deceased was able to coordinate with the cruise line's port agent to send the body back to the United States.

Generally speaking, the first large port city the ship calls at is where the body will be offloaded, taken to a medical examiner's office and repatriated. But each country has its own rules and regulations about accepting bodies, declaring cause of death and repatriating remains.

That's where consular offices come in handy. U.S. consulates, for instance, will help the family of the deceased in making arrangements with local authorities for preparation and disposition of the remains. They'll even serve as provisional conservator of the person's estate if no one else is able to do it.

Who Pays for Repatriation?

Neither the consulate nor the cruise line pays for anything related to bringing a loved one home; they only help the family make arrangements. And repatriation, with all its necessary paperwork and hassle, is not inexpensive.

Make sure your trip insurance plan includes repatriation as that will cover the bulk of these expenses. Depending on the insurance company, you may also get help sorting through all the paperwork and requirements.

So, while no one wants to talk about the possibility of death during a cruise, if you or someone you're sailing with is ill or in the later years of life, purchasing a travel insurance policy is highly recommended by cruise industry insiders.

© 1995— 2024 , The Independent Traveler, Inc.

Causes of Death, Australia

Statistics on the number of deaths, by sex, selected age groups, and cause of death classified to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)

Key statistics

- The mortality rate remained low in 2021 (507.2 per 100,000 people).

- Ischaemic heart disease was the leading cause of death.

- Suicide was the 15th leading cause of death.

- There were two deaths from Influenza, a record low.

- The rate for Alcohol-induced deaths was the highest in 10 years.

Revised causes of death data now available

Revised cause of death data is now available (as of 14/04/2023) for the following:

- For coroner certified death data for the years 2019-2021, and,

- for Western Australian doctor certified death data for the years 2016-2020.

Changes to cause of death data are outlined in a series of technical notes accessed via the methodology link on this page. Two data cubes (16 and 17) are also available containing this revised data. These can be accessed via the data downloads tab on this page. See Revisions to causes of death for links to these resources.

Articles linked to this topic page including 2021 in Review, Leading causes of death and Intentional self-harm do not incorporate the revised data. The annual Causes of Death, Australia, 2022 publication will incorporate these revisions in full when released in the last quarter of this year.

Crisis support services, 24 hours, 7 days

Some of these statistics may cause distress. Services you can contact are detailed in blue boxes throughout this publication and in the Crisis support services section at the end of the publication.

- Lifeline : 13 11 14

- Suicide Call Back Service : 1300 659 467

- Beyond Blue : 1300 224 636

- MensLine Australia : 1300 789 978

- 13YARN : 13 92 76

- Kids Helpline (for young people aged 5 to 25 years): 1800 551 800

- National Alcohol and Other Drugs Hotline: 1800 250 015

The ABS uses, and supports the use of, the Mindframe guidelines on responsible, accurate and safe reporting on suicide, mental ill-health and alcohol and other drugs. The ABS recommends referring to these guidelines when reporting on statistics in this report.

2021: Mortality during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic

Australia recorded significantly lower than expected mortality during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic with death rates reaching historical lows. Deaths decreased across many causes, but the decrease in respiratory disease deaths was most notable. The experience of Australia was different from that of many other countries, where significant increases in mortality were recorded, due largely to deaths from COVID-19.

As Australia entered the second year of the pandemic, COVID-19 continued to circulate with the Delta variant emerging and triggering public health response measures. The roll out of COVID-19 vaccines began in February 2021. Monitoring patterns of mortality during 2021 remained important, with Provisional Mortality Statistics reports continuing to provide timely insights into the direct and indirect effects of the virus on patterns of death. These reports showed that the mortality rate remained low during 2021 with key causes certified by a doctor being cancers, ischaemic heart diseases and dementia. These provisional reports did not include information on the causes of coroner referred deaths due to the time required to complete coronial investigations.

With the majority of information on 2021 deaths now available, the Causes of Death report is able to provide a more complete picture of deaths registered in 2021, including preliminary cause of death information for coroner referred deaths and other key mortality indicators such as leading causes of death.

2021: Overview of key mortality indicators

2021: all cause mortality by sex.

To show the mortality pattern over the last decade, age-standardised death rates (SDRs) are presented below for males, females and persons.

- The mortality rate remained low at 507.2 deaths per 100,000 people.

- Whilst this was a 3.2% increase on the previous year, the mortality rate in 2020 was at a historical low.

- Mortality rates increased from 2020 by 2.3% for males and 4.1% for females, but remained below 2019 rates.

- Download table as CSV

- Download table as XLSX

- Download graph as PNG image

- Download graph as JPG image

- Download graph as SVG Vector image

- Age-standardised death rate. Death rate per 100,000 estimated resident population as at 30 June (mid year). See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies and Glossary sections of the methodology for further information.

- Deaths registered between 2017-2018 from Victoria that were lodged with the ABS in the 2019 reference year have been presented by registration year to enable more accurate time-series analysis. See Technical note: Victorian additional registrations and time series adjustments in Causes of Death, Australia 2019 methodology for detailed information on this issue.

- All causes of death data from 2006 onward are subject to a revisions process - once data for a reference year are 'final', they are no longer revised. Affected data in this table are: 2012 - 2018 (final), 2019 (revised), 2020 and 2021 (preliminary). See the Data quality section of the methodology and Causes of Death Revisions, 2018 Final Data (Technical Note) and 2019 Revised Data (Technical Note) in Causes of Death, Australia, 2020.

- See the Data quality section of the methodology for further information on specific issues related to interpreting time-series and 2021 data.

2021: All cause mortality by age

Data is presented in the table below as age-specific death rates (ASDRs) for selected age groups. In 2020, age-specific death rates decreased for all age groups. In contrast, 2021 saw an increase in ASDRs for all age groups except those aged 25-44, which continued to decline.

- The death rate for those aged 25-44 was the lowest in the 10-year time series.

- In 2020, the largest proportional rate decrease was for females aged 85 and over (6.9%). The mortality rate for this cohort increased by 5.6% in 2021, signifying a return to expected mortality rates.

- ASDRs for those aged 85 and over were similar to those seen in 2018, which was a year of particularly low influenza and pneumonia mortality.

- Almost all ASDRs remained below 2019 rates, excluding those for females aged 0-24.

- Age-specific death rates reflect the number of deaths for a specific age group, expressed per 100,000 of the estimated resident population as at 30 June (mid year) of that same age group. See the Glossary section of the methodology for further information.

2021: Top five leading causes of death

Leading causes of death give an indication of the health of a population and help to ensure that health resources are directed to where they are needed most.

- The top five leading causes of death remained the same.

- All of the top five leading causes recorded increases in their (crude) mortality rates. This follows a decrease in all of these causes during the first year of the pandemic.

- The rate difference between ischaemic heart diseases and dementia continues to narrow – in 2017 the mortality rate of ischaemic heart disease was approximately 38% higher than deaths due to dementia. In 2021 the rate was approximately 9% higher.

- Excluding 2020, both the number and rate of deaths due to ischaemic heart diseases (IHD) have been decreasing over time. While there was a 4.5% increase in the number of deaths due to IHD in 2021, this follows a 7.4% decrease between 2019 and 2020.

- Crude death rates due to dementia were the highest in the time series.

- All top five leading causes of death are non-communicable diseases (they are not passed from person to person).

- Crude death rate. Death rate per 100,000 estimated resident population as at 30 June (mid year). See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies and Glossary sections of the methodology for further information.

- All causes of death data from 2006 onward are subject to a revisions process - once data for a reference year are 'final', they are no longer revised. Affected data in this table are: 2017 - 2018 (final), 2019 (revised), 2020 and 2021 (preliminary). See the Data quality section of the methodology and Causes of Death Revisions, 2018 Final Data (Technical Note) and 2019 Revised Data (Technical Note) in Causes of Death, Australia, 2020.

2021: Respiratory disease mortality

Respiratory diseases include acute manifestations such as influenza and pneumonia as well as chronic diseases such as emphysema, asthma and interstitial lung disease.

Tracking respiratory diseases through the COVID-19 pandemic has provided valuable insights into the success of public health measures. Many acute respiratory diseases (such as influenza and some types of pneumonia) are transmitted via droplets, so measures put in place to prevent the spread of COVID-19 can also reduce the spread of other communicable diseases. In addition, people with chronic lung diseases can be particularly vulnerable to poor outcomes from contracting infectious diseases such as influenza and COVID-19. Historically, respiratory disease mortality rates have reflected the severity of the annual influenza season, with higher rates observed during years with severe flu seasons such as 2017 and 2019.

- The mortality rate from respiratory diseases remains low at a rate of 39.1 per 100,000 people.

- This is the second lowest mortality rate on record from respiratory diseases (after 2020).

- There was a 3.5% increase in the mortality rate from respiratory diseases from 2020.

- The increase in 2021 was driven by deaths due to chronic respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and interstitial lung disease.

Acute respiratory diseases:

- There were 2 people who died from influenza, which is the lowest number of annual flu deaths on record. This compares to 55 in 2020 and 1,076 in 2019.

- Influenza and pneumonia as a combined group decreased by 12.5% from 2020. This follows a 45.9% decrease in 2020 after a high influenza mortality rate in 2019.

- Pneumonia is a common terminal cause of death, especially for older people who have long term chronic conditions. There was an increase of 2.3% in the rate of influenza and pneumonia as an associated cause of death. However, this remains 28.3% lower than the pre-pandemic rate (2015-2019 average).

- For those who died with pneumonia as a terminal cause, the most common underlying causes of death were dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (14.7%), chronic lower respiratory diseases (13.9%), and COVID-19 (6.1%).

2021: COVID-19 mortality

COVID-19 is a respiratory infection caused by the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. On 11 March 2020 the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic. Mortality data for 2021 largely covers deaths that occurred during the Delta wave of the pandemic, which began in Australia in mid-2021 and continued through to the end of the year. Further information relating to COVID-19 mortality in Australia, including 2022 data, can be found here .

- There were 1,122 deaths due to COVID-19 registered in 2021.

- 98.9% occurred during the Delta wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (July – December 2021). The ABS do not receive information on specific variants of COVID-19, and this information is based on date of death only.

- COVID-19 was the 34th leading cause of death.

- There were a further 31 people who died of other causes (e.g., cancer), with COVID-19 as a contributory cause of death.

The profile of people who died from COVID-19 during the Delta wave differed from those who died during Waves 1 and 2 of the pandemic. Of these Delta wave deaths:

- The median age at death was 79.1. This compares with a median age of 86.9 in 2020.

- Over half were male (660 male deaths, 462 female deaths). In 2020, just over half the people who died from COVID-19 were female.

- Pneumonia was the most common acute disease outcome and was present in 60.0% of COVID-19 deaths in 2021, compared with 31.2% of COVID-19 deaths in 2020.

- Cardiac conditions were the most commonly reported pre-existing conditions (287 deaths). The most commonly reported pre-existing condition in 2020 was dementia including Alzheimer’s disease.

- New South Wales (557 deaths) and Victoria (553 deaths) had the highest number of deaths. In 2020, most deaths occurred during Wave 2 in Victoria.

- COVID-19 is coded to ICD-10 codes U07.1 and U07.2.

- Includes only deaths where COVID-19 was the underlying cause of death.

- Causes of death data for 2021 are preliminary and subject to a revisions process. See Data quality, Revisions process in the methodology for more information.

COVID-19 vaccine-related deaths

2021 also saw the introduction of COVID-19 vaccinations globally. The World Health Organization subsequently issued the ICD-10 emergency code U12.9 (COVID-19 vaccines causing adverse effects in therapeutic use). This code allows COVID-19 vaccine-related deaths to be identified separately from deaths involving adverse reactions to other vaccines and biological substances.

The source of all cause of death data for the ABS is either the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death for doctor certified deaths, or the pathology report or coronial findings for coroner referred deaths (accessed via the National Coronial Information System). This includes deaths which may be caused by the COVID-19 vaccine. Independent analysis and interpretation of deaths data by authorities such as the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) is not conveyed to the ABS or reflected in coding outputs. Due to the scope of the ABS deaths collection, data received and published by the ABS may differ from data collected through the TGA's independent investigations into COVID-19 vaccine-related deaths. The ABS and the TGA have communicated and understand that there are differences in how a death may be categorised as being related to a COVID-19 vaccine. These differences may include scope (as described) and the timing of coding and investigations (the TGA regularly updates data in relation to vaccines, whereas the ABS is reporting on coded data at a point in time). The ABS and the TGA will continue to work together to ensure that datasets remain consistent as possible whilst taking into account the known differences in each agency’s reporting scopes.

- In Australia in 2021, there were 15 deaths for which the information provided to the ABS indicated that COVID-19 vaccination was the underlying cause of death.

- Of these, 13 were certified by a coroner and 2 were certified by a doctor.

- Ten of these deaths involved vaccine-induced thrombocytopaenic conditions.

- The majority of deaths (92.3%) assigned as being due to the COVID-19 vaccine have open coronial cases meaning they are in scope of the ABS revisions process. Additional information will be reviewed by the ABS in relation to these deaths as it is received.

As of October 6 2022, the TGA has identified 14 reports where the cause of death was linked to vaccination. Further details on the TGA’s vaccine safety monitoring process can be found here.

Completeness of coroner referred deaths data in 2021

Deaths that are referred to a coroner can take time to be fully investigated, which subsequently affects the availability of data to the ABS for cause of death coding. Each year, some coroner cases are coded by the ABS before the coronial proceedings are finalised. Coroner cases that have not been closed or had all information made available can impact on data quality as less specific ICD codes often need to be applied.

At the time of coding 2021 data, there was a higher proportion of open coroner cases than at the time of preliminary coding in previous years (67.2% in 2021 versus a 5-year average for 2015-2019 of 56.2%). This is reflected in the 2021 dataset by a higher proportion of deaths due to 'other ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality' (R99). Cases coded to R99 made up 9.8% of the coroner referred deaths dataset in 2021, compared with a historical average of 6.3% for preliminary data. Of the 2021 coroner referred cases, 74.6% are open cases that fall within the scope of the ABS causes of death revisions process.

Causes of death data for 2021 would ordinarily be revised in early 2024. In light of the information detailed above, an early revision of 2021 data will be conducted during the upcoming revisions cycle in 2023. This revision will target open cases currently coded to 'other ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality' (R99), 'exposure to unspecified factor' (X59) and 'unspecified event, undetermined intent' (Y34), with the aim of enhancing the specificity of the codes applied to these cases by capturing additional coronial information made available since initial coding.

Causes of death with a high proportion of coroner referred deaths (e.g. suicide, assault and drug-induced deaths) should be interpreted with caution due to the expectation that these data will change during revisions.

- This graph includes coroner referred deaths data only.

- All causes of death data from 2006 onward are subject to a revisions process. Data in this table reflect codes assigned during preliminary coding only and are not comparable with final (2012 - 2018) and revised (2019) data presented elsewhere in this publication. See Data quality, Revisions process in the methodology for more information.

- This table includes coroner referred deaths data only.

- Data in this table are presented by the state in which the death was registered. Causes of death data by state of usual residence can be found in the Data downloads section of this publication.

2021: Potentially avoidable mortality and selected external causes of death

Support services, 24 hours, 7 days.

- Lifeline : 13 11 14

- 1800RESPECT : 1800 737 732

- National Alcohol and Other Drugs Hotline: 1800 250 015

- Family Drug Support : 1300 368 186

For further information see Crisis support services .

2021: Potentially avoidable mortality

Potentially avoidable deaths are defined as deaths from conditions that are potentially preventable through individualised care and/or treatable through existing primary or hospital care (METeOR, 2021). They include both natural diseases, including many types of cancer, ischaemic heart disease, diabetes and infectious diseases, and external causes of death (e.g. suicide, assault) of people aged under 75.

On average, 40% of potentially avoidable deaths are referred to a coroner (compared with 11-14% of all deaths). The following data is preliminary for 2021 and 2020 - interpretation should take into account that numbers of potentially avoidable deaths will increase when the ABS revisions process is applied. See Completeness of coroner referred deaths data in 2021 for further information.

For people who died from potentially avoidable causes in 2021:

- There were 26,967 people who died from potentially avoidable causes (17,113 males and 9,854 females). This compares to 26,995 deaths in 2020 (17,231 males and 9,764 females).

- The mortality rate is the lowest in the ten year time series for both males and females.

- While the mortality rate has decreased, the sex ratio has remained relatively constant at 1.8 (male to female).

- Potentially avoidable deaths are classified according to the National Healthcare Agreement: PI 16- Potentially Avoidable Deaths, 2021 Classification: https://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/725797 .

- Deaths registered between 2017-2018 from Victoria that were lodged with the ABS in the 2019 reference year have been presented by registration year to enable more accurate time-series analysis. See Technical note: Victorian additional registrations and time series adjustments in Causes of Death, Australia 2019 methodology for detailed information on this issue.

2021: Suicides

The following data is preliminary for 2021 and 2020 - interpretation should take into account that numbers of deaths due to suicide will increase when the ABS revisions process is applied. Revised data for deaths due to suicide in 2021 will be published in early 2023. See Completeness of coroner referred deaths data in 2021 for further information.

For people who died by suicide in 2021:

- There were 3,144 deaths due to suicide (2,358 males and 786 females). This compares to 3,139 suicides in 2020 (2,384 males and 755 females).

- The suicide rate was 12.0 deaths per 100,000 people, similar to that recorded in 2020 (12.1).

- The suicide rate increased for females and decreased for males.

- The median age at death for people who died by suicide was 44.8 (45.8 for males and 42.9 for females).

- Suicide remained the 15th leading cause of death.

- Almost 90% of people who died by suicide had risk factors identified including psychosocial stressors, mental health conditions, chronic diseases, and substance abuse disorders.

- The data presented for intentional self-harm includes ICD-10 codes X60-X84 and Y87.0. Care needs to be taken in interpreting figures relating to intentional self-harm. See the Deaths due to intentional self-harm (suicide) section of the methodology in this publication.

- To best reflect a more accurate time series, deaths due to suicide are presented by registration year. As a result, some totals may not equal the sum of their components and suicide data presented in this publication may not match that previously published by reference year. Care needs to be taken when interpreting data derived from Victorian coroner referred deaths including suicide. See Technical note: Victorian additional registrations (2013-2016) in the methodology for more information.

2021: Motor vehicle accidents

For people who died from a motor vehicle accident in 2021:

- There were 1,206 deaths from motor vehicle accidents (917 males and 289 females). This compares to 1,163 in 2020 (870 males and 293 females).

- The death rate from motor vehicle accidents increased by 2.9% from 2020, but remained 7.0% lower than the 2019 rate.

- The rate increased for males and decreased for females.

- For males, those aged under 25 had the largest numerical increase with 36 more deaths than in 2020.

- For females, the rate decrease was driven by those aged under 35, with 31 fewer deaths in this group than in 2020.

- The data presented for motor vehicle accidents includes ICD-10 codes V00-V79 and V89.2.

2021: Assaults

The following data is preliminary for 2021 and 2020 - interpretation should take into account that numbers of deaths due to assault are expected to increase when the ABS revisions process is applied. Revised data for deaths due to assault in 2021 will be published in early 2023. See Completeness of coroner referred deaths data in 2021 for further information.

For people who died due to assault in 2021:

- There were 213 deaths due to assault (152 males and 61 females). This was lower than the number of deaths in 2020 (241 deaths).

- The rate of assault mortality decreased slightly from 0.9 to 0.8 in 2021. This is the lowest rate seen in the ten-year time series.

- The number and rate of deaths due to assault decreased for both males and females.

- The largest numerical decrease was for males aged between 35 and 44 (16 fewer deaths than in 2020).

- The data presented for assaults includes ICD-10 codes X85-Y09 and Y87.1.

2021: Drug-induced deaths

Drug-induced deaths are those which are directly attributable to drug use. They include deaths due to acute drug toxicity (e.g. overdose) and due to chronic drug use (e.g. drug-induced cardiac conditions).

On average, 97% of drug-induced deaths are certified by a coroner. There are multiple complex factors which need to be considered when a death is certified as drug induced. The timing between the death and toxicology testing can influence the levels and types of drugs detected, making it difficult to determine the true level of a drug at the time of death. Individual tolerance levels may also vary considerably depending on multiple factors, including sex, body mass and a person’s previous exposure to a drug. Contextual factors around the death must also be considered such as pre-existing natural disease and reports from informants (e.g., friends and families) regarding the circumstances surrounding death. For these reasons, the certification of a death as being drug-induced can take significant time to complete, making these deaths particularly sensitive to the revisions process.

The following data is preliminary for 2021 and 2020 - interpretation should take into account that numbers of drug-induced deaths will increase when the ABS revisions process is applied. Revised data for drug-induced deaths in 2021 will be published in early 2023. See Completeness of coroner referred deaths data in 2021 for further information.

For people who died of a drug-induced death in 2021:

- There were 1,704 drug-induced deaths (1,069 males and 635 females). This compares to 1,842 in 2020 (1,187 males and 655 females).

- There was an 8.2% decrease in the rate of drug-induced deaths from 2020.

- Deaths registered in Victoria had the greatest rate decrease since 2020 (16.1%).

- The rate decrease from 2020 was greater for males than females (10.4% and 3.8% respectively).

- Opioids were the most common drug class identified in toxicology for drug-induced deaths.

- The data presented for drug-induced deaths in this publication is based upon a tabulation with both acute and chronic effects of drugs. See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies section of the methodology for the complete tabulation.

np not available for publication

- Data in this table are presented by the state in which the death was registered. Data for drug-induced deaths by state of usual residence can be found in the data downloads section of this publication.

2021: Alcohol-induced deaths

Alcohol-induced deaths are those where the underlying cause can be directly attributed to alcohol use, including acute conditions such as alcohol poisoning or chronic conditions such as alcoholic liver cirrhosis.

On average, 71% of alcohol-induced deaths are certified by a doctor. These deaths are primarily caused by chronic alcohol-induced conditions. As a result, alcohol-induced deaths data are less likely to be impacted by revisions than causes with a higher proportion of coroner referred deaths such as drug-induced deaths and suicides.

For people who died of an alcohol-induced death in 2021:

- There were 1,559 people who died of an alcohol-induced death (1,156 males and 403 females).

- There was a 5.8% increase in the rate of alcohol-induced deaths, with 107 additional deaths since 2020.

- For males, the rate is the highest in the ten year time series at 8.3 deaths per 100,000 people (8.1% increase since 2020).

- The rate for females remained the same as in 2020.

- The rate increase over the last 10 years is largely due to conditions associated with long term alcohol use including liver cirrhosis.

- Alcohol-induced deaths includes ICD-10 codes; E24.4, G31.2, G62.1, G72.1, I42.6, K29.2, K85.2, K86.0, F10, K70, X45, X65, Y15.

Australia's leading causes of death, 2021

- In 2021 there were 171,469 deaths, with an age-standardised death rate of 507.2 deaths per 100,000 people.

- Ischaemic heart disease was the leading cause of death, accounting for 10.1% of all deaths.

- The rank order of the top 5 leading causes has remained the same since 2018.

- Influenza and pneumonia did not appear in the 20 leading causes of death for the first time in the ten year time series.

- There were 1,122 deaths from COVID-19, ranking as the 34th leading cause of death.

Leading causes of death

There were 171,469 deaths registered in Australia in 2021.

In 2021 for people who died:

- 52.1% were male (89,401) and 47.9% were female (82,068).

- Their median age at death was 82.0 years (79.4 for males, 84.8 for females).

- The top five leading causes accounted for more than one-third of all registered deaths.

Identifying and comparing leading causes of death in populations is useful for tracking changes in patterns of mortality and identifying emerging trends. For more information related to the tabulation of leading causes, see the Methodology section of this publication.

- The leading cause of death was Ischaemic heart disease.

- Dementia, including Alzheimer's disease was the second leading cause of death. People who died from dementia had a high median age at death of 89.2.

- Cerebrovascular diseases, lung cancer and chronic lower respiratory diseases rounded out the top five leading causes.

- Deaths from the five leading causes all increased from 2020. This followed a decrease of all of the five leading causes in 2020, with many causes of death recording historical low mortality rates in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The number of influenza and pneumonia deaths remained low in 2021. Influenza and pneumonia was not in the top 20 leading causes in 2021 (ranked 22nd).

- There were only 2 deaths recorded as being due to influenza, the lowest on record.

- Suicide was the 15th leading cause of death. People who died by suicide had a median age at death of 44.8.

- COVID-19 was the 34th leading cause of death, with 1,122 deaths recorded through the civil registration system.

From 2012 to 2021:

- Deaths due to Ischaemic heart diseases and Cerebrovascular diseases decreased by 13.8% and 9.1% respectively.

- Deaths due to Dementia, including Alzheimer's disease increased by 53.8% (5,573 deaths).

- Causes listed are based on the WHO recommended tabulation of leading causes. See Mortality tabulations and methodologies for further information.

- See the Data quality section of the methodology for further information on specific issues related to interpreting time-series and 2021 data.

- All causes of death data from 2006 onward are subject to a revisions process - once data for a reference year are 'final', they are no longer revised. Affected data in this table are: 2012, 2016 (final), 2020 and 2021 (preliminary). See the Data quality section of the methodology and Causes of Death Revisions, 2018 Final Data (Technical Note) and 2019 Revised Data (Technical Note) in Causes of Death, Australia, 2020.

- See the Classifications and Mortality coding sections of the methodology for further information on coding of 2021 data.

- Care needs to be taken in interpreting figures relating to intentional self-harm. See the Deaths due to intentional self-harm (suicide) section of the methodology in this publication.

- Care needs to be taken when interpreting data derived from Victorian coroner referred deaths including suicide. See Technical note: Victorian additional registrations and time series adjustments in Causes of Death, Australia 2019 methodology for detailed information on this issue.

- n/a Not applicable. There are no deaths due to COVID-19 before 2020.

- Deaths due to suicide are presented by registration year throughout this publication. As a result, some totals may not equal the sum of their components and suicide data presented in this publication may not match that previously published by reference year.

Age-standardised death rates

Age-standardised death rates enable the comparison of death rates over time as they account for changes in the size and age structure of the population. Refer to Mortality tabulations and methodologies, Age-standardised death rates (SDRs) in the Methodology section of this publication for more information.

For age-standardised death rates from 2012 to 2021:

- Ischaemic heart diseases decreased by 32.0%.

- The gap between ischaemic heart disease and dementia has narrowed.

- While the number of dementia deaths has increased over the 10 year period, the age-standardised death rate for dementia has been more stable. This reflects the ageing population in Australia.

- Cerebrovascular diseases decreased by 28.9%.

- Malignant neoplasms of trachea, bronchus and lung (lung cancer) and Chronic lower respiratory diseases decreased by 18.0% and 9.5%, respectively.

- Causes listed are based on the WHO recommended tabulation of leading causes. See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies section of the methodology for further information.

Years of potential life lost

Years of potential life lost (YPLL) is a measure of premature mortality which weights age at death to gain an estimate of how many years a person would have lived had they not died prematurely. Causes of death with a median age less than the life expectancy will have a higher number of YPLL. When considered in terms of premature mortality, the leading causes of death have a notably different profile. Refer to Mortality tabulations and methodologies - Years of potential life lost (YPLL) in the Methodology section of this publication for more information.

- Suicide was the leading cause of premature death with 107,068 YPLL. People who died by suicide had a median age at death of 44.8.

- Ischaemic heart disease had the highest number of premature deaths but had the second highest number of YPLL at 70,308 years. People who died from ischaemic heart disease had a median age at death of 84.3.

- People who died from Lung cancer, Motor vehicle crashes and Accidental poisoning had the 3rd, 4th and 5th highest YPLL, with median ages at 74.7, 45.9 and 45.4, respectively.

- For information on WHO leading causes and YPLL see the Mortality tabulations and methodologies section of the methodology.

- See the Classifications and Mortality coding sections of the methodology for further information on coding of 2021 data.

- The data presented for intentional self-harm includes ICD-10 codes X60-X84 and Y87.0. Care needs to be taken in interpreting figures relating to intentional self-harm. See Deaths due to intentional self-harm (suicide) in the methodology for more information.

Leading causes of death by sex - Males

For the 89,401 males who died in 2021:

- Ischaemic heart disease was the leading cause of death (10,371 deaths), remaining considerably higher than the second ranked cause (dementia at 5,664 deaths).

- Prostate cancer was the sixth leading cause of death and second leading cause of cancer deaths.

- Suicide was the 10th leading cause. Three-quarters of people who died by suicide were male.

- COVID-19 was the 33rd leading cause, accounting for 660 male deaths.

Influenza and pneumonia was not in the top 20 leading causes for males in 2021 (ranked 23rd).

For males from 2012 to 2021:

- The age-standardised death rate (SDR) for Ischaemic heart diseases decreased by 29.2%.

- The SDR for Dementia, including Alzheimer's disease increased by 19.6%.

- The SDR for lung cancer decreased by 23.0%.

- For information on WHO leading causes and age-standardised death rates see the Mortality tabulations and methodologies section of the methodology.

- Care needs to be taken in interpreting figures relating to intentional self-harm. See Deaths due to intentional self-harm (suicide) in the methodology for more information.

- Age-standardised death rate. Death rate per 100,000 estimated resident population as at 30 June (mid year). See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies and Glossary sections of the methodology for further information.

Leading causes of death by sex - Females

For the 82,068 females who died in 2021:

- Dementia including Alzheimer's was the leading cause of death (10,276 deaths).

- The death rate for dementia increased by 21.5% over the last decade. Close to two-thirds of people who died from dementia were female.

- Ischaemic heart disease was the second leading cause with 6,960 deaths.

- Breast cancer was the sixth leading cause overall and second leading cause of cancer deaths with 3,129 deaths.

- COVID-19 was the 32nd leading cause, accounting for 462 female deaths.

- Deaths due to falls are the most common external cause of death. Falls were the 12th leading cause of death for females.

Leading causes of death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

In 2021, there were 4,081 deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (2,229 males and 1,852 females). The table below presents for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: numbers of deaths, crude death rates and age-standardised mortality rates for each jurisdiction in 2021. Age-standardised rates enable the comparison of populations with different age structures.

- Ischaemic heart disease was the leading cause of death (411 deaths).

- There were 17 deaths due to COVID-19 in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

- The Northern Territory recorded the highest mortality rate.

- All causes of death data from 2006 onward are subject to a revisions process - once data for a reference year are 'final', they are no longer revised. 2021 data is preliminary. See the Data quality section of the methodology and Causes of Death Revisions, 2018 Final Data (Technical Note) and 2019 Revised Data (Technical Note) in Causes of Death, Australia, 2020 (cat. no. 3303.0).

- Age-standardised death rate. Death rate per 100,000 estimated resident population as at 30 June (mid year). See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies and Glossary sections of the methodology for further information.

- Crude death rate. Death rate per 100,000 estimated resident population as at 30 June (mid year). See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies and Glossary sections of the methodology for further information.

- Rates presented in this table have been calculated using Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population estimates and projections based on the 2016 Census. As a result, these rates may differ from those previously published. See the Mortality tabulations and methodologies section of the methodology for further information.

Leading causes of death for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by five jurisdictions: NSW, Qld, WA, SA, NT

Measures of mortality relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are key inputs into the Closing the Gap strategy. This strategy aims to enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to overcome inequality and achieve life outcomes equal to all Australians across areas such as life expectancy, mortality, education and employment. In July 2020 all Australian governments committed to 17 targets under the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (Australian Government, 2020). Mortality data will continue to be a key indicator to measure progress against these targets.

Methods for reporting on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths: Data reported in the remainder of this article are compiled by jurisdiction of usual residence for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory only. These jurisdictions have been found to have a higher quality of identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin allowing more robust analysis of data. Data for those with a usual residence in Victoria, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory is unsuitable for comparisons of changes over time, and have been excluded in the remainder of article. Data presented in this release may underestimate the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who died.

For further information see Deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Methodology section of this publication.

In 2021 there were 3,696 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who died across the five jurisdictions.

- Their median age was 62.5 years.

- Ischaemic heart disease was the leading cause of death for males.

- Diabetes was the leading cause of death for females for the first time since 2013.

- Those who had a usual residence in the Northern Territory had the highest mortality rate.

Age-standardised death rates over time

To measure changes over time for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, age-standardised death rates for males, females and all persons are presented in the graph below.

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who died between 2012 and 2021:

- The highest age-standardised death rate (SDR) occurred in 2020 at 966.3 deaths per 100,000 people.

- The SDR is consistently higher for males compared to females.

- The rate ratio ranged between 1.2 to 1.3 male deaths for every female death.

- All causes of death data from 2006 onward are subject to a revisions process - once data for a reference year are 'final', they are no longer revised. Affected data in this table are: 2012 - 2018 (final), 2019 (revised), 2020 and 2021 (preliminary). See the Data quality section of the methodology and Causes of Death Revisions, 2018 Final Data (Technical Note) and 2019 Revised Data (Technical Note) in Causes of Death, Australia, 2020 (cat. no. 3303.0).

- Data are reported by jurisdiction of usual residence for NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT only. Data for Victoria, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory as data quality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait identification is not considered to be as robust in these jurisdictions. For further information see Deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the Methodology section of this publication.

- See the Classifications and Mortality coding sections of the methodology for further information on coding of 2021 data.

Top five leading causes of death of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- The five leading causes of death (Ischaemic heart diseases, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases, lung cancer and suicide) accounted for over one-third of all deaths.

- The five leading causes of death have remained the same between 2012-2016 and 2017-2021.