Jerry Goldsmith

Star trek, voyager, television series main title theme, avg duration, description.

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

PDF Playlist

Theme (From "Star Trek: Voyager")

Nic raine , jerry goldsmith , prague philharmonic orchestra.

Follow 1 fan

Jerry Goldsmith

Jerrald King "Jerry" Goldsmith (February 10, 1929 – July 21, 2004) was an American composer and conductor most known for his work in film and television scoring. more »

The easy, fast & fun way to learn how to sing: 30DaySinger.com

become a better singer in only 30 days , with easy video lessons.

Sheet Music PDF Playlist

Written by: Jerrald Goldsmith

Lyrics © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC

Lyrics Licensed & Provided by LyricFind

Discuss the Theme (From "Star Trek: Voyager") Lyrics with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Use the citation below to add these lyrics to your bibliography:

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"Theme (From "Star Trek: Voyager") Lyrics." Lyrics.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 7 Apr. 2024. < https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/2076758/Jerry+Goldsmith/Theme+%28From+%22Star+Trek%3A+Voyager%22%29 >.

Missing lyrics by Jerry Goldsmith?

Know any other songs by jerry goldsmith don't keep it to yourself, image credit, the web's largest resource for, music, songs & lyrics, a member of the stands4 network, browse lyrics.com, our awesome collection of, promoted songs.

Get promoted

Are you a music master?

"ground control to major tom -- take your ______ pills and put your helmet on.", free, no signup required :, add to chrome, add to firefox, on radio right now.

Powered by OnRad.io

Think you know music? Test your MusicIQ here!

- April 6, 2024 | ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Showrunner Explains Why They Reopened A TNG Mystery To Start Season 5

- April 5, 2024 | Roddenberry Archive Expands With Virtual Tours Of Deep Space 9 Station And The USS Discovery

- April 5, 2024 | Podcast: All Access Reviews The First Two Episodes Of ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Season 5

- April 4, 2024 | Recap/Review: ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Embraces Second Chances In “Under The Twin Moons”

- April 4, 2024 | Recap/Review: ‘Star Trek: Discovery’ Returns With New Vitality And A Lore-Fueled Quest In “Red Directive”

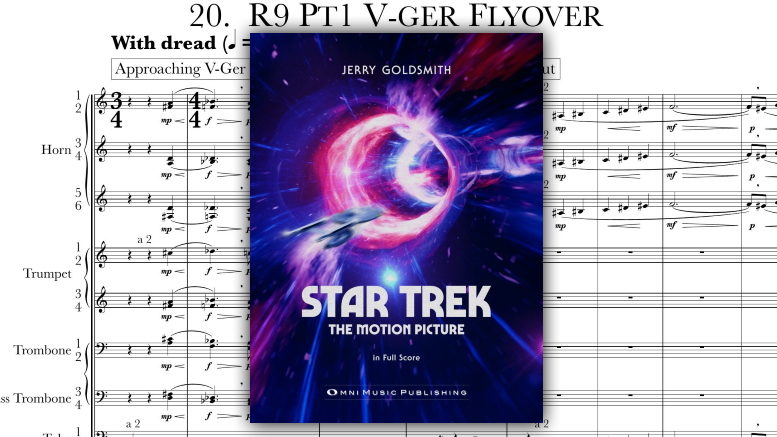

Jerry Goldsmith’s Full Orchestral Score For ‘Star Trek: The Motion Picture’ Published As Book For First Time

| April 14, 2021 | By: Lukas Kendall 12 comments so far

Fans of composer Jerry Goldsmith and Star Trek music now have a new way to celebrate his Oscar-nominated score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture .

Omni Music Publishes Star Trek: The Motion Picture Score Book

Now that dozens of Star Trek soundtrack albums have been released by the specialty CD labels as expanded collector’s editions, Omni Music is opening a new frontier by publishing Jerry Goldsmith’s legendary score to Star Trek: The Motion Picture as a bound book. This is the first full, complete orchestral score released for any Star Trek music from film or television.

This unique book features the written, full orchestrations to Goldsmith’s magnificent score for the first Star Trek feature film. The orchestrations are intended for large symphony orchestra (enhanced by specialty instruments) so this isn’t something you could easily use to play the music at home on your keyboard; in fact, the book is licensed for study only, and not performance. The full printed score corresponds to the 3-CD set of The Motion Picture soundtrack album released by La-La Land Records in 2012 .

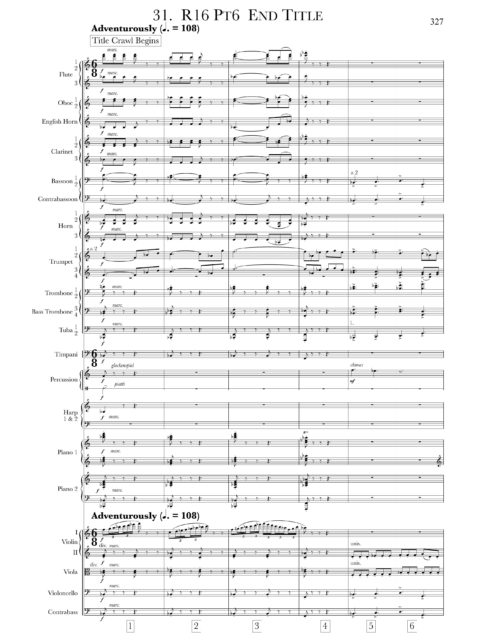

Sample page from Star Trek: The Motion Picture score book (Omni Publishing)

Omni Music Publishing is a specialty book company dedicated to publishing film scores in full, unabridged editions for fans, scholars, and music aficionados. While publishing classical music is pretty straightforward, doing the same for film scores is much more complicated due to dealing with the rights. There is also the archaeology work of locating the handwritten (and often, quite messy) original scores in studio vaults and engraving them (via computer) so that they are clear and legible. Omni has sorted through the red tape and undertaken the painstaking work to bring these treasures officially to the public.

Jerry Goldsmith’s score to Star Trek: The Motion Picture became the signature piece of Star Trek film music, with a main theme repurposed for Star Trek: The Next Generation (at Gene Roddenberry’s request) and also used by Goldsmith himself in his sequel scores for Star Trek V: The Final Frontier , First Contact , Insurrection, and Nemesis . It features a beautiful love theme (“Ilia’s Theme”) and magnificent, ominous passages for the alien V’Ger threat, enhanced by pipe organ and a unique instrument called the blaster beam. The score overflows with melody and orchestral invention.

Because of the film’s troubled postproduction, Goldsmith wrote and recorded a number of alternate cues which were never heard until being presented on La-La Land’s 3CD set. All of them are included in a supplemental section of this book—along with four additional selections which Goldsmith wrote and had orchestrated, but which were never recorded in 1979, for one reason or another.

And the score all comes together in a beautiful 473-page, 9” x 12” bound softcover book. If you can’t read music, this will admittedly be like browsing a book published in a foreign language—but could still a beautiful collectible, with new cover art by Scott Saslow. The Star Trek: The Motion Picture score book can be purchased directly from Omni for $85.00 .

Visit Omni Music Publishing’s website to order and see other books in their catalog, such as The Matrix (Don Davis), Batman (Danny Elfman), Glory (James Horner) and Ghostbusters (Elmer Bernstein).

And if you are a musician looking for Star Trek sheet music to play at home with piano or other instruments, you can find a selection at musicnotes.com .

Bonus: TMP scene with unused “Body Meld” music

As a special treat for TrekMovie readers, composer Joe Kraemer ( Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation , Jack Reacher ) has created a synthesized “mockup” of one of the unrecorded cues, Goldsmith’s original intended version of the climactic “Body Meld” (available in the new printed full score). Judge for yourself if Robert Wise was right to reject it for being “too romantic.”

Lukas Kendall is the founder of Film Score Monthly and has been involved as a producer or consultant on numerous soundtrack album releases of Star Trek music. He is credited as a proofreader in Omni’s book edition of Star Trek: The Motion Picture .

Related Articles

Books , Feature Films (TMP-NEM) , Music

Read: Exclusive Excerpt From ‘The Jerry Goldsmith Companion’ On Scoring ‘Star Trek: The Motion Picture’

Music , Star Trek: Picard

See ‘Star Trek: Picard’ Season 3 Orchestra Pay Homage To Jerry Goldsmith, With Score From New Composer

Awards , Celebrity , Feature Films (TMP-NEM) , Music , Trek on TV

Jerry Goldsmith Finally Gets Star On Hollywood Walk of Fame For Star Trek and Other Work

ENT , Interview , Music , Review , Soundtrack

REVIEW – Star Trek: Enterprise Collection, Volume 2

ooooohhhhh I really like this but, I the original is better suited.

That font! 🥰

Over a long period of time I’ve learnt to appreciate TMP a lot more. It still not one of my absolute favourites but the score most certainly is. I will go out on a limb here and say it’s still the finest Star Trek score of all time. It’s pretty magical. Jerry Goldsmith you still very much missed.

The blaster beam has such a distinctive sound- really sets TMP score apart from the other films.

I bought one, and purchased the big CD release back when it was new. Great companion/set.

The score is all at concert pitch, so if you want to plunk out the parts at your piano, you don’t have to transpose. This also makes it easier to see doublings, etc. As usual, viola parts are in alto clef.

I’ve not seen a film score before, so maybe rendering everything at concert pitch is standard in that industry? (Not so with other music… I’m mostly a choral conductor and composer but have conducted instrumental ensembles a bit, too.)

It depends on the composer. Most of the “old guard” asked their orchestrators to use transposed pitch; ST:TMP (Arthur Morton) was all done transposed. All of John Williams’ orchestrations are transposed. James Horner had his orchestrators use concert pitch (like Prokofiev). I am told that nowadays, concert pitch is much more common for today’s composers who are less likely to be classically trained.

Thanks for the info. Neat to be on this topic with Trek fans… my worlds of interest converge!

Thanks Lukas.

Well this is a super painful story. This is like showing us the ingredients of a cake and we have no access to getting the ingredients or putting it together.

I’m assuming most fans won’t even be able to read the recipes (to stay with your analogy), let alone recreate them. This kind of book probably has a very small target audience.

This reminds me that Star Trek is famous for introducing god-like or very very powerful beings, and then having absolutely zero follow-up. The Organians, Metrons… and THIS–a follow-up somewhere along the way would have been welcome. In fact, the only follow-through we’ve ever had with a god-like being has been Q. And even then, he’s still quite a mystery.

Beautiful music. Amazing how those themes imprint on your memory.

Max Steiner Biographer Breaks Down How the ‘King Kong’ Composer ‘Established the Grammar of Film Music’

By Chris Willman

Chris Willman

Senior Music Writer and Chief Music Critic

- Intuit Dome Books Bruno Mars for Two-Night Grand Opening, as Venue Looks to Stand Out Amid L.A. Concert Arena Scene 2 days ago

- Lucius Signs With Fantasy, Will Release Re-Recorded Version of Seminal ‘Wildewoman’ Allbum 2 days ago

- Toby Keith to Get All-Star Salute on CMT Music Awards Featuring Lainey Wilson, Brooks & Dunn, Lukas Nelson and More (EXCLUSIVE) 3 days ago

Steven C. Smith ’s first book, 1991’s “A Heart at Fire’s Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann,” preceded — and arguably helped precipitate — a huge uptick of interest in that once neglected, now practically deified film composer. Almost three decades later, he’s published his second biography, “Music by Max Steiner: The Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer.” Smith, a scoring historian and Emmy-nominated TV producer, wouldn’t mind prompting a similar surge of consideration for the career of Steiner, whose filmography of nearly 300 films included “ King Kong ,” “ Gone with the Wind ,” “ Casablanca ,” “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” and “The Searchers.” Variety spoke with Smith about his long-aborning second book.

VARIETY: Is there a good case to be made that Steiner’s music for “King Kong” in 1933 is the most important film score of all time?

SMITH: I think there’s no greater way to turn someone off something than to say it’s the greatest or most important. But I will say that on a historic level, “King Kong” is the most influential music score of all time. Because it completely established the grammar of film music in a way that composers ever since, to the present day, still look at and say, “Oh, that’s how you score a film.” A lot of people think “King Kong” is the first film score ever written. It’s not — Steiner himself had been writing for film for about a year at that point — but it’s the first motion picture classic that has a great score.

He’s the one who first put it all together at the dawn of the talkies, this idea of how to write orchestral music under and around dialogue — something that producers and directors really were very suspicious of in the first years of sound film. They didn’t want music in dramatic films. It was okay if it was a musical. And Steiner is the guy who figured out not just how to write music around dialogue, but how to write themes for characters and shape them subtly throughout a film — exactly what John Williams does in a “Star Wars” film, or the composers for a Marvel film do today. There are so many devices that he uses, whether it’s the way he writes a love theme for Ann that becomes a theme of absolute terror for her as the film goes on, or the way that Kong’s theme starts off being about the horror and power of a monster and, by the end, has become an elegy for a fallen antihero.

And Steiner is the one who made film music a medium that did not just simply repeat what we already see but revealed what characters are thinking, which remains one of the most powerful things that film music can do.

Even if the character whose thinking is revealed through the music is… a giant monkey.

If you watch “Kong” and pay attention to the music, you’ll notice that it initially makes us feel the grandeur and force of Kong, but it also gradually takes us inside his mind and shows his feelings for Ann — call them love, call them whatever. It’s the music that really makes that character transition, so that by the time that Kong is captured and taken to New York, he starts to become a figure of pathos, if still a frightening one, especially when he escapes and wreaks havoc. When he falls, the finale is one of the greatest pieces of dramatic music written for film. I had seen “Kong” dozens of times, but it wasn’t till I wrote the book that I realized every little phrase of music in the last two minutes of the film is all based on different little thematic pieces of score he wrote. He’s basically recapping the whole movie for us in this very sad, touching way and pulling it all together.

Does Steiner get his due today?

One of the reasons I wanted to write this book was to show the person who created a whole industry, but who many people have forgotten. … [But] Steven Spielberg’s nickname for John Williams is apparently Max, as an affectionate little nod. And what is the name of Spielberg’s first son? Max. I’m not saying he named him after Max Steiner , but it’s safe to say Spielberg is very appreciative of his place in film music. Danny Elfman has said part of the reason he became a film composer was because of Steiner and “King Kong.” Jerry Goldsmith said, also referring to “King Kong,” “I’m doing what I’m doing because of it.” When “Star Wars” was being put together, among the composers on the temp track before Williams was hired was Steiner; George Lucas has said he wanted a Korngold/Steiner kind of a score. So is Steiner relevant? Well, is “Star Wars” relevant?

You have a story in the book about how disrespected he was the one time he tried to conduct a concert of his film music, which went disastrously.

During his life, film music was held in total contempt by the symphony world. The one time he was invited to conduct, the members of the New York Philharmonic treated him horribly. Max claimed that the lead cellist wouldn’t even take his instrument out of the case during rehearsal. He never tried to conduct a concert again. Now, many symphony orchestras have survived because they play film music, because they either show a film like “Casablanca” with the score played live or they play an evening of film music in suites, and much of it is still Steiner’s. Max didn’t really believe in an afterlife, but I would love to think that somehow he knows his music is heard in these places now.

He was ahead of his time in wanting to pull that off, even if his music wasn’t destined to make it to concert halls until long after his death. Are there other ways in which he was ahead of the curve, on some really practical level?

Since this is Variety , we should say that Max Steiner is one of the reasons that today’s film composers receive the residuals they do. When Max got into film music, ASCAP was not collecting any money for scores, unless it was a song published as sheet music or a record was sold, which was not very often in those days. And Max fought a 27-year battle with ASCAP, and with others, saying that film music is music and film composers should be rewarded for what they do. He united the industry, really — and he did it with many other people; I’m not saying he did it single-handedly. But Max, really starting in 1933, led the battle that is really ultimately the reason why — when composers’ work is shown on television, when it’s streamed, when a single music cue or a whole soundtrack is downloaded onto our phones — why composers get those royalties. So for that alone, we should remember the name Max Steiner.

His scores are known for being extremely accessible — that’s clearly one reason he got so much work — but you bring out the subtlety and brilliance of how he could repeat or transmute themes over the course of a score, in a way that you’d virtually have to be a genius to catch while the film is actually unfolding. And during his lifetime, very few people ever heard his scores twice, to be able to study them in that way.

His music is extremely sophisticated, and also it’s the kind of music that you don’t have to know is sophisticated to just enjoy it. Even Max himself… A friend of mine, John Morgan, would point out to Max, “It’s so interesting how you took Errol Flynn’s theme and then made Olivia de Havilland’s theme is a variation on that, and then this third theme is sort of a combination of those.” And Max would say, “You know, I never thought of that.” Someone wrote an entire book on the score of “Now,” Voyager,” which won Steiner one of his three Oscars, about how all this music subtly intersects and tells us things we wouldn’t know otherwise, and it’s all absolutely valid. And I suspect that Max didn’t think about two-thirds of that. He was very intuitive, and yet beneath that intuition there was incredible subtlety and sophistication, and it was all just pouring out of him.

One of the things he was very conscious about, though, you say in the book, was writing around the tonality of actors’ voices.

He was so concerned that the music not fight the dialogue or sound effects or whatever needed to be heard along with it, that he would determine, say, where Bette Davis’s voice was — if it was a musical note, where it would be on a musical scale — and he would write his music in a key that was above or below her voice. So for someone with a low voice like Orson Welles, whom he scored once, he wrote a little above Welles’ very low baritone. And in the score for “Jezebel,” which is a film that won Bette Davis a best actress Oscar, he writes in his notes to the orchestrator he’ll be handing his score to exactly what the musical pitch of Davis’ voice is, and how he’s writing above and below it. He did that for his whole career. And I think that’s astonishing, how detail-oriented he could be in a situation where there was phenomenal pressure on him to write an enormous amount of music in a very short time with very little sleep.

Your previous biography subject, Herrmann, was clearly a classic sort of tortured artist, right there on the surface. But Steiner joked about his angst. Not just personally, but he literally wrote constant gags into the margins of all his scores, much of which you reproduce. And you also reproduce jokes he told in an unpublished memoir he worked on. This all adds up to “Music by Max Steiner” being a book with a lot of laughs in it — more so than “A Heart at Fire’s Center,” which doesn’t have a lot of personal levity from its subject. But did the fact that Steiner could be personally convivial and lovable, on top of being endlessly prolific, work against his genius being taken as seriously as it should, compared to Herrmann’s?

It’s worth remembering that Max came from Vienna. As a child he knew Johann Strauss Jr., who wrote “The Blue Danube” and these effervescent, romantic, light-as-air but beautiful waltzes. That world at the turn of the century was this amazing time of Strauss music and Gustav Klimt paintings and Freud beginning to develop his theories —there was both a seriousness and a lightness to Vienna at the time. And I think that’s part of what gave Max that wonderful quality of playfulness and a love of life. He wasn’t the handsomest man. He was rather short. He could be wisecracking, and there was always a cigar in his mouth, so you could really picture a kind of Hollywood stereotype. But he was deeply romantic. I mean, think of the music to “Casablanca” — that’s really Max’s soul.

And so one of the things that makes Steiner so fascinating is that he was a funny guy. He was very intense about his music, but he wanted to have fun. Bernard Herrmann, although he had a very wry sense of humor, was a rather tortured man who was in a lot of pain for much of his life. Max was a fun-loving, very well-liked workaholic who was a great artist as well. Knowing that Steiner worked on up to 300 films, that he loved alcohol, cigars and playing cards, that he got married a lot [four times] and told a lot of bad jokes, you might think, “Oh, right, a studio guy — Hollywood hack. He probably farmed out the work to a lot of people. He was about the money.” But he cared deeply. He was an intuitive man who was brilliant in his craft, and kind of like Michael Curtiz, he didn’t advertise it. For decades, Curtiz [the director of “Casablanca”] was kind of written off because he worked on so many different types of films, and now we see him as someone who directed many of the greatest films and did have a voice. It’s much the same with Steiner.

But he was like Herrmann in that he was a very sensitive person, in the good and bad senses of the word. And by that, I mean very empathic to characters and stories, but also very easily hurt and quick to be injured in his own feelings, which many artists are. I think all of that added to why he could be so empathic with Rick Blaine in “Casablanca” or Scarlett O’Hara.

Although he’s sometimes remembered for his jauntier or brassier scores or action pictures, you make the point he might have excelled most at “women’s pictures,” like “Now, Voyager.”

Bette Davis once said, “He was my composer.” She understood what he brought to her films. Now, she probably also said some sharp words about him from time to time, like she did everyone. But I’m fascinated by how this very masculine, wise-cracking as you say, sometimes in private with the guys kind of loose, dirty-joke-telling guy could be so in touch with that very feminine quality of that interior quality of the characters in his films.

He loved beauty, and when he saw Ingrid Bergman in “Casablanca” or Vivien Leigh in “Gone With the Wind,” he was very affected by them — not just on a level of seeing a beautiful woman, but he really fell in love with those characters, and then he stepped back to be them. So as a man, he was very drawn in. He could be Humphrey Bogart, if you will, and feel that intoxicating romance, but then he could also channel — and this is something he certainly never talked about — this incredible feminine side and write the voice of Bette Davis in “Dark Victory” in which she’s dying, or “Now, Voyager,” when she is this repressed woman emerging, and write music that is completely from her soul.

Do you have a Steiner score you think is most underrated?

A great score he wrote for a film that’s really forgotten now is “Johnny Belinda.” That was one of his favorites. It’s a beautiful score for a film that is both very dark and very hopeful. It has very modern music in that it has very dark music that sounds like the kind of scratchy, harsh violin sound that a Jerry Goldsmith might’ve done later in the ’60s or ’70s, for an excruciating rape sequence. But it also has this beautiful theme of childlike lyricism for this woman who can’t speak and who can’t hear. I think when Max was at his best was when he would be given a story about someone with great vulnerability and desperately seeking love and being in pain.

He loved writing for those kinds of films, much more than he liked writing an action movie. The movies he dreaded doing were movies that were wall-to-wall action because in those days, when composers had to physically write every single note with their hands, he would say, only half-kidding, “I will be blind by the end of this film.” And indeed he lost most of his eyesight over his lifetime. But I think what unites his best scores is his empathy for human longing and and desire and romance. “Mildred Pierce” is a great score.

Howard Hawks hired Max specifically for “The Big Sleep,” and I think that’s a sign that he didn’t want it to be a movie that was a mystery, so much. He wanted to play up this kind of almost screwball romance and certainly the romantic intensity between Bogart and Bacall, who were having an affair during the filming of that movieHawks, who had worked with Max once before, knew that Steiner would really bring out the sexiness of the movie.

The book goes into his family psychology a great deal, suggesting that he became a workaholic in part because he wanted to make good on what was lost after his very successful father fell from grace. And then that workaholism causes him to ignore a wife he seemed to at least theoretically want to remain close to, and their young son, with tragic results.

Part of his story is how he wanted to redeem the legacy of his father and grandfather back in Vienna. “Gone With the Wind” is a story ultimately about a character who is trying to restore a lost family dynasty. Take away the dated aspects — the frankly offensive aspects of the film with the Civil War and its racial depictions — put all that aside and you can see how Max saw the film, which is not a movie about the Civil War, but about someone trying to regain a family and ironically losing great love that is close to that person at the same time. That was true of Scarlett O’Hara, and it turned out to be true of Max’s life as well. He reclaimed that family name, but at considerable personal cost.

There is tragedy to go around toward the end of the book, personally. But one of the things that may come as a relief to the reader is that, unlike so many figures from the golden age of Hollywood, his is not a story of a quick rise followed by a long, protracted fall into irrelevance. Thirty years or so into his film career, he produces one of his great scores in “The Searchers,” and then has a fluke pop blockbuster with “Theme from ‘A Summer Place’.”

That’s a gift to a biographer. This is a man who worked with George Gershwin and Jerome Kern, who worked on all these shows that had classic American standards in them; Max was often the conductor conducting the theater orchestra of those great Broadway shows of the ’20s. Then he becomes the musical director of the Astaire/Rogers series for the first three years, so he’s the man conducting “Cheek to Cheek” and all the great songs from “Top Hat,” “Follow the Fleet,” “The Gay Divorcee,” etc. So Max knew all of the great songwriters, and he desperately wanted to have hit songs like an Irving Berlin and a Gershwin. And although certainly Max is one of the great melodists of the 20th century — I mean, if you’ve seen “Gone With the Wind” once, you could probably think of the theme — he didn’t write popular songs the way a Gershwin did. He kept trying and trying, and some of them deserved a better fate, but they just didn’t catch on with people.

He had all but given up when he was hired to score “A Summer Place,” which was considered kind of trashy, even though it was a big Warner Brothers movie with stars and a big budget. It was about teenagers wanting to have sex and their horny parents, things that as the production code was starting to fall were outraging older moviegoers and titillating younger moviegoers. Max, being always aware of the music of his time and listening to the kind of Fats Domino/”Blueberry Hill” triplet that we think of as rock ‘n’ roll in the ’50s… as a friend of his said, as soon as Max had that rhythm, he couldn’t help but write a kind of nice melody over it.

He had stopped trying to write a hit song. Well, that was the one that became a hit record. In one of the great kind of underdog stories or ironies of musical history, a 71-year-old composer from Vienna, born in 1888, had the No. 1 instrumental bestseller of the early rock era. It won record of the year at the Grammys over Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Elvis Presley, Ray Charles. You can certainly debate that choice, but you can’t debate the fact that people loved this song. And it made Max so much money just as he was winning his battle over over royalties in film music. He was set financially at the age of 71 after being broke almost all of his life, after owing the equivalent of well over half a million dollars or more to the government. His accidental pop hit is one of the great “how to succeed without really trying” stories.

More From Our Brands

‘snl’: watch raye perform ‘escapism,’ ‘worth it’, putter’s paradise: the $39 million pebble beach estate wants to help you sharpen your short game, alabama, uconn share analytical mindset—and even used same firm, the best loofahs and body scrubbers, according to dermatologists, snl video: matt damon, paul rudd, ryan gosling and more welcome kristen wiig to the five-timers club, verify it's you, please log in.

- More to Explore

- Series & Movies

Published Sep 15, 2013

The Trek Series With The Best Theme Music Is...

Well, this was just a little unexpected. StarTrek.com asked readers to cast their votes as to which Star Trek series had the best theme music, and The Next Generation won. Now, that's not the surprise. What shocked us was that 25,000 people voted and The Original Series came in dead last. Here are the results:

Here's what some of your fellow fans had to say about the options:

"Jerry Goldsmith is kicking some rear end with the top two places so far for a combined 53%." -- Carl James

"The Enterprise theme song is the best!! At first I thought it was cheesy but now I love it. It reminds me of an awesome power ballad from the 80's." -- Ange Hertz

" TNG , no contest, though most of them had good theme music." -- Cole Whiteley

"I understand people's dislike for Enterprise's theme music - it really was a drastic change from what came before, and, in a way, didn't really 'fit' with the other themes, but I like the song a lot personally, and I think it suits Trek very well in feel - the song is celebrating the need to explore, to wander, and to have confidence in yourself, defying the odds against you. It's a powerful song." -- Matthew B. R. Sims

" Voyager because its song tells the story in itself... "persevere." Next Gen is nice but was a derivative of The Motion Piicture ." -- S. James Chorvat II

"Both Star Trek: the Motion Picture (and the Next Gen theme) and the Voyager theme were written by Jerry Goldsmith. Goldsmith won the Emmy for Voyager 's theme. Every time I hear that climatic high note, then the sound affect of Voyager passing through a planet's ring on the up-beat, I still get warm fuzzies all up and down my spine. Voyager 's theme is a musical, visual, and sound design masterwork." -- Michele Hansen

" DS9 has the best orchestration. Voyager is good, too. TNG is a nice march. TOS is very 1960s, so it's dated. The pop sound and vocals make the Enterprise stand out--love it or hate it. Give me DS9 every time." -- Charles Kufs

"I love the original theme of Star Trek . I like the other Star Trek series, but I love the original better..." -- Curtis Simpkins

"I have always loved DS9 's opening theme. It's majestic." -- Vicki Love

Get Updates By Email

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

Soundtracks

Now, voyager.

- Night and Day (1932) (uncredited) Written by Cole Porter Played offscreen on piano at the pre-concert party

- Symphony No. 6 in B Minor (Pathétique) , Op. 74 (1893) (uncredited) Written by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky First movement (Adagio - Allegro non troppo) played at the concert Also played as part of the score

- Perfidia (1939) (uncredited) Music by Alberto Domínguez Played as dance music in the Rio Club

- Yankee Doodle (ca. 1755) (uncredited) Traditional music of English origin Variation in the score when the Statue of Liberty is onscreen

- In An Old Dutch Garden (By An Old Dutch Mill) (1940) (uncredited) Music by Will Grosz Played in the drugstore where Charlotte takes Tina for ice cream

Contribute to this page

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More from this title

More to explore.

Recently viewed

Screen Rant

Star trek: picard subtly reused voyager’s theme tune perfectly.

A musical homage during an emotional moment between Jean-Luc Picard and Seven Of Nine evoked the epic, soaring Star Trek: Voyager theme song.

Star Trek: Picard honored one of its predecessors, Star Trek: Voyager , by evoking its much loved theme song. Star Trek: Picard has been a surprising well of knowledge for Voyager fans; Seven Of Nine is set to play a prominent role after being introduced in "Stardust City Rag," which also saw the grisly death of a minor character from the series.

After thwarting her attempts to exact murderous vengeance against an intergalactic arms dealer who chopped up her friend for parts, Jean-Luc Picard and Seven Of Nine have a conversation that surely set the hearts of Trek fans aflutter. Picard and Seven are the most prominent ex-Borg characters in all of Star Trek , though they had never met before this episode. They didn't have much time to get acquainted when Seven surprisingly boarded the La Sirena, as Picard hastily enlisted her to help him track down Bruce Maddox , the cyberneticist who created the twin androids Dahj and Soji Asha from bits of the late Lieutenant Commander Data's engrams.

Related: Star Trek: Every Android Brent Spiner Played (& What Happened To Them)

Yet in a quiet moment after all the action, Seven has an uncharacteristically vulnerable moment with Picard. She asks Picard if he felt he had regained his humanity after his assimilation, to which he replied he did. Seven specifies, asking Picard if he felt he'd recovered all of his humanity, which he's forced to admit he does not. It's a tender moment for what seems to be two ships passing in the night, as Seven goes off to pursue her prey and Picard rushes off to the Borg Artifact to save Soji. And as Seven steps atop the La Sirena's transporter pad, a brief section of the Voyager theme song can be heard.

The suitably soaring original theme song was composed by the late Jerry Goldsmith. Goldsmith didn't score Star Trek: The Original Series, yet he's probably composed more memorable Star Trek themes than any other single person. His epic score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture was famously reused as the theme song to Star Trek: The Next Generation , and he would go on to score three of the four TNG films.

Voyager rarely ranks at the top of fans' favorites lists - it suffered from notoriously inconsistent quality and a thin supporting cast over its seven seasons - but the theme song is an all-timer. It seems a sure thing Seven will be crossing Picard's path again; there's no way they could tease a major Borg connection like Seven without a bigger payoff. Yet even if this were the last fans saw of Seven on Star Trek: Picard , her exit sounded suitably mighty.

Next: Star Trek Theory: Romulans Hate Androids Because They Themselves ARE Artificial

Engineers Pinpoint Cause of Voyager 1 Issue, Are Working on Solution

Engineers have confirmed that a small portion of corrupted memory in one of the computers aboard NASA’s Voyager 1 has been causing the spacecraft to send unreadable science and engineering data to Earth since last November. Called the flight data subsystem (FDS), the computer is responsible for packaging the probe’s science and engineering data before the telemetry modulation unit (TMU) and radio transmitter send the data to Earth.

In early March , the team issued a “poke” command to prompt the spacecraft to send back a readout of the FDS memory, which includes the computer’s software code as well as variables (values used in the code that can change based on commands or the spacecraft’s status). Using the readout, the team has confirmed that about 3% of the FDS memory has been corrupted, preventing the computer from carrying out normal operations.

The team suspects that a single chip responsible for storing part of the affected portion of the FDS memory isn’t working. Engineers can’t determine with certainty what caused the issue. Two possibilities are that the chip could have been hit by an energetic particle from space or that it simply may have worn out after 46 years.

Although it may take weeks or months, engineers are optimistic they can find a way for the FDS to operate normally without the unusable memory hardware, which would enable Voyager 1 to begin returning science and engineering data again.

Launched in 1977 , the twin Voyager spacecraft flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune. They are both exploring interstellar space, outside the bubble of particles and magnetic fields created by the Sun, called the heliosphere. Voyager 2 continues to operate normally.

News Media Contact Calla Cofield Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. 626-808-2469 [email protected]

Theme from Star Trek

- View history

The "Theme from Star Trek " (originally scored under the title "Where No Man Has Gone Before" [1] and also known informally as the " Star Trek Fanfare ") is the instrumental theme music composed for Star Trek: The Original Series by Alexander Courage . First recorded in 1964 , it is played in its entirety during the opening title sequences of each episode. It is also played over the closing credits, albeit without its signature opening fanfare.

During the opening credits, the theme's opening fanfare is accompanied by the now-famous "Space: the final frontier" monologue spoken by William Shatner (with the exception of the pilot episodes, " The Cage " and " Where No Man Has Gone Before "). Throughout the opening credits, the theme is punctuated at several points by the USS Enterprise flying towards and past the camera. These "fly-bys" are accompanied by a "whoosh" sound effect created vocally by Courage himself. (Documentary: Music Takes Courage: A Tribute to Alexander Courage )

- 1 Conception and original use

- 2 Vocalization and lyrics

- 3 Later use

- 4 Other recordings and uses

- 5 External link

Conception and original use [ ]

Creator Gene Roddenberry originally approached composer Jerry Goldsmith to write the theme for Star Trek . Goldsmith, however, had other commitments and instead recommended Alexander Courage. ( Star Trek: The Motion Picture (The Director's Edition) commentary)

Courage was not a science fiction fan, referring to the genre as "marvelous malarkey." He thus saw the theme he was writing as "marvelous malarkey music." Courage composed, orchestrated and conducted the theme in one week. He drew inspiration from a Richard A. Whiting song he heard on the radio as a child called "Beyond the Blue Horizon". This song had a drawn-out tune with a steady, fast-paced beat underneath it, which Courage emulated when composing the theme. (Documentary: Music Takes Courage )

The theme used in " The Cage " – the unaired first pilot – featured a wordless melody line by soprano Loulie Jean Norman supported by electronic underpinnings. When a second pilot was ordered and the series was picked up, Norman's vocalizations were dropped from the theme.

The first season of The Original Series used two versions of the theme. On the original NBC and syndicated runs, five episodes – "Where No Man has Gone Before", the second pilot, along with " The Man Trap ", " Charlie X ", " The Naked Time ", and " Mudd's Women " – used a mixed electronic/orchestral arrangement for the opening credits, with the main melody line created electronically and accompanied by more traditional instrumentation, including a flute and an organ for both the opening and closing themes. When the series was remastered for video in the early 1980s, only "Where No Man Has Gone Before" retained this version of the theme over both the opening and closing credits, while the opening was restored to the other four episodes and placed on five others when the series was remastered again for DVD release. The closing credits for the other nine episodes, however, used a version that had only an orchestral arrangement. The mixed arrangement was first heard on " The Corbomite Maneuver " (the tenth episode aired, although it was the second episode produced), after which the show opened with the orchestral-only arrangement.

Vocalization and lyrics [ ]

For the second and third seasons , Loulie Jean Norman's wordless accompaniment was re-added to the theme. However, Norman's voice was made more prominent than it was for "The Cage".

When originally written (and as heard in "The Cage"), Courage had Norman's vocalizations and the various instruments mixed equally to produce a unique sound. According to Courage, however, Gene Roddenberry had it re-recorded with Norman's accompaniment at a higher volume above the instruments, after which Courage felt the theme sounded like a soprano solo. Roddenberry's version can be heard during the opening credits of each episode in the second and third seasons; Courage's version is heard during the closing credits.

Further souring the relationship between Roddenberry and Courage, Roddenberry wrote lyrics to the theme without Courage's knowledge – not in the expectation that they would ever be sung, but in order to claim a 50% share of the music's performance royalties. Although there was never any litigation, Courage commented that he believed Roddenberry's conduct was unethical, to which Roddenberry responded, " Hey, I have to get some money somewhere. I'm sure not going to get it out of the profits of Star Trek . " [2] Although the lyrics were never included on the series, they have been printed in several "TV Theme" songbooks over the years.

Later use [ ]

Portions of the Theme from Star Trek have been used in all 13 Star Trek feature films . Most of the Star Trek films' opening themes start by quoting the opening fanfare from Courage's theme, before seguéing into the film's own theme. However, there are multiple exceptions to this tradition. Star Trek: The Motion Picture did not use the fanfare at all in the opening or closing music, although a subdued version of the Theme from Star Trek was created by Courage at the request of the film's main composer, Jerry Goldsmith . [3] This arrangement of the theme was used for the " Captain's Log " cues. The theme was quoted again in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home , most extensively in the final scenes.

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country , scored by Cliff Eidelman , broke with the tradition again. The Theme from Star Trek did not appear in the opening music, although it was used towards the end. Star Trek Generations , scored by Dennis McCarthy , on the other hand, did use the fanfare in the opening credits (and extensively throughout the score) but it did not appear until the end of the main title music.

The score for Star Trek , composed by Michael Giacchino , again did not use the fanfare in the opening title music: instead, Giacchino subtly quoted the opening notes and various other Star Trek themes from past films throughout his score. For the end credits, a re-arranged version of the Theme from Star Trek , fully orchestrated and with The Page La Studio Voices accompanying the melody line, was used. This version was also used for the end credits of Star Trek Into Darkness and Star Trek Beyond .

The theme's opening fanfare was adapted by Dennis McCarthy as the opening for the Star Trek: The Next Generation theme (the remainder of which was an adaptation of Goldsmith's theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture ). Courage's original theme can also be heard in the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode " Trials and Tribble-ations ", the Star Trek: Voyager episode " Shattered ", and the Star Trek: Enterprise series finale, " These Are the Voyages... "

Courage's theme was re-recorded for the remastered Star Trek episodes , with Elin Carlson emulating Norman's wordless vocalization.

Star Trek: Discovery composer Jeff Russo included Courage's fanfare at the end of the Discovery main titles. The theme returned in full at the end of the Season 1 finale, " Will You Take My Hand? ", playing over the closing credits after the USS Discovery intercepts a distress call from the USS Enterprise .

In the Star Trek: Strange New Worlds episode " Spock Amok ", at least a portion of the theme became diegetic (heard in the fictional universe) when a few notes of the fanfare could be heard on the PADD used to keep track of tasks for " Enterprise bingo ".

Other recordings and uses [ ]

TOS star Nichelle Nichols recorded a disco version of the theme. However, Nichols used different lyrics than those written by Gene Roddenberry. The late jazz musician Maynard Ferguson and his band also recorded a rendition of the song, a fusion version that was released on his 1977 album Conquistador . Ferguson's version was used as the opening theme for The Larry King Show on the Mutual Radio Network. The satirical rock band Tenacious D and the lounge band Love Jones recorded versions of the theme, as well, using Gene Roddenberry's lyrics.

Roy Orbison was a Star Trek fan and often opened his concerts with his band jamming to theme. [4]

The 1992 Paramount Pictures comedy Wayne's World was the first non- Trek film to use Courage's theme. In the film, the character of Garth Algar (played by Dana Carvey ) whistles the theme while he and Wayne Campbell ( Mike Myers ) lie on the hood of Wayne's car, looking up at the stars. When Garth finishes the tune, he tells Wayne, " Sometimes I wish I could boldly go where no one's gone before. But I'll probably just stay in Aurora. " The theme can also be heard in the films Muppets from Space (1999, starring F. Murray Abraham ) and RV (2006, starring Robin Williams and featuring Brian Markinson ).

At the 2005 Primetime Emmy Awards, TOS star William Shatner and opera singer Frederica von Stade performed a live version of the theme, with Shatner reciting the opening monologue and von Stade singing the wordless melody line.

In 2009, the theme was used as the wake-up call for the crew of mission STS-125 aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis .

For the 2021 inauguration of US President Joe Biden , acclaimed cellist Yo-Yo Ma played the fanfare of the theme as a prelude to his performance of another song significant to Star Trek , " Amazing Grace ". [5]

External link [ ]

- Theme from Star Trek at Wikipedia

- 3 USS Antares (32nd century)

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The theme begins with a sense of adventure and exploration, reflecting the core essence of the Star Trek franchise. As Voyager embarks on its treacherous journey through uncharted space, this music becomes a beacon of hope and determination. The uplifting melody symbolizes the resilience of the crew as they face countless challenges and strive ...

Although a theme by Jerry Goldsmith is the basis of the title music for the series Star Trek: The Next Generation, it was not until Star Trek: Voyager that Goldsmith, one of Hollywood's finest and most admired feature film composers, wrote an original theme for one of the Star Trek TV series.. The Voyager theme, which combines qualities of heroism and yearning, was an outstanding aural tag for ...

The following individuals wrote movie scores, theme music, or incidental music for several episodes and/or installments of the Star Trek franchise. Other composers who contributed music to at least one episode include Don Davis, John Debney, Brian Tyler, George Romanis, Sahil Jindal, Andrea Datzman, and Kris Bowers.

The main title theme of Star Trek: Voyager, composed by Jerry Goldsmith.

Dennis McCarthy (born July 3, 1945) is an American composer of television and film scores. His soundtrack credits include several entries in the Star Trek franchise, including underscores for The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, Enterprise, and the 1994 feature film Star Trek Generations. His other television credits include Dynasty, V, MacGyver, Sliders, Dawson's Creek, and Project ...

Jerry Goldsmith (10 February 1929 - 21 July 2004; age 75) was a film and television composer and conductor who wrote the musical scores for five Star Trek films and the main title themes for two Star Trek spin-off series. He was nominated for eighteen Academy Awards, winning one, and also won five Emmy Awards. He was also nominated for the 1980 Saturn Award for "Best Music" for Star Trek ...

Dennis McCarthy (born 3 July 1945; age 78) is a composer who has written many Star Trek-related musical scores, including the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine main title theme and the Star Trek: Enterprise end credits theme. He also composed the music for Star Trek Generations and many episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Star Trek: Voyager and Star Trek ...

Released: 1995. Length: 10:24. Reference (s): GNPD 1405. Star Trek: Voyager - Main Title was a single released by GNP Crescendo Records in 1995. It contained several versions of the title theme from Star Trek: Voyager.

He composed music for three additional movies, as well as wrote the main title theme for Star Trek: Voyager. Whether it was for film or television, where Star Trek was concerned, Goldsmith was omnipresent. Sadly, Jerry Goldsmith passed in 2004.

I really enjoyed the Star Trek Voyager series. The casting of Kate Mulgrew as Captain Janeway was a great choice. I also that the character Seven Of Nine als...

Oh, love like ours is never, ever free (free) We got to pay some agony if we wanna have ecstasy (for the ecstasy), oh. Hey, got to pay some agony. If we wanna have an ecstasy, yeah eah. And we need each other desperately, don't we, baby. And I'll never from you be free, no, no. So you'll have to do the leavin' me, yeah.

A visualization of the theme from the 90s TV show Star Trek: Voyager composed by Jerry Goldsmith.More at https://music.oliverbrown.me.uk

My eyes started to well up when the Voyager theme appeared in 1×10. Definitely getting this soundtrack. ... All 3 of those composers wrote pieces that could cut you to the core and bring out a ...

Jerry Goldsmith's score to Star Trek: The Motion Picture became the signature piece of Star Trek film music, with a main theme repurposed for Star Trek: The Next Generation (at Gene Roddenberry ...

Max Steiner Biographer Breaks Down How the 'King Kong' Composer 'Established the Grammar of Film Music'. Steven C. Smith 's first book, 1991's "A Heart at Fire's Center: The Life ...

Star Trek has featured some of the most iconic theme songs of all time, generally scoring the final frontier with thrilling orchestral marches. From the very beginning, with Star Trek: The Original Series, the music was an important part of the show.And while the types of music used to score the actual episodes has evolved over the years, the theme song remains consistent - in all but one case ...

Every time I hear that climatic high note, then the sound affect of Voyager passing through a planet's ring on the up-beat, I still get warm fuzzies all up and down my spine. Voyager's theme is a musical, visual, and sound design masterwork." -- Michele Hansen "DS9 has the best orchestration. Voyager is good, too. TNG is a nice march.

This is my own arrangement of the theme from the Paramount television series Star Trek: Voyager which aired from 1995-2001. The original composition is by J...

Now, Voyager. Edit. Night and Day (1932) (uncredited) Written by Cole Porter. Played offscreen on piano at the pre-concert party. Symphony No. 6 in B Minor (Pathétique), Op. 74 (1893) (uncredited) Written by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. First movement (Adagio - Allegro non troppo) played at the concert.

Star Trek: Picard honored one of its predecessors, Star Trek: Voyager, by evoking its much loved theme song. Star Trek: Picard has been a surprising well of knowledge for Voyager fans; Seven Of Nine is set to play a prominent role after being introduced in "Stardust City Rag," which also saw the grisly death of a minor character from the series.. After thwarting her attempts to exact murderous ...

Star Trek: Voyager soundtracks have been released by GNP Crescendo Records and La-La Land Records since the series premiered in 1995. Releases [] Title Release date Cover "Caretaker" 1995: Star Trek: Voyager - Main Title: 1995: Star Trek: Voyager Collection: 2017: Star Trek: Voyager Collection, Volume Two:

NASA engineers have traced the Voyager 1 spacecraft's transmitted gibberish to corrupted memory hardware in its flight data system (FDS). "The team suspects that a single chip responsible for storing part of the affected portion of the FDS memory isn't working," NASA wrote in an update. Gizmodo reports: FDS collects data from Voyager's science instruments, as well as engineering data about the ...

Launched in 1977, the twin Voyager spacecraft flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune. They are both exploring interstellar space, outside the bubble of particles and magnetic fields created by the Sun, called the heliosphere. Voyager 2 continues to operate normally. News Media Contact Calla Cofield

The "Theme from Star Trek" (originally scored under the title "Where No Man Has Gone Before" [1] and also known informally as the "Star Trek Fanfare") is the instrumental theme music composed for Star Trek: The Original Series by Alexander Courage. First recorded in 1964, it is played in its entirety during the opening title sequences of each episode. It is also played over the closing credits ...