Important note about COVID Red Settings:

At Orange our libraries are open with face masks required. Vaccine passes are no longer required. Please stay home if you are unwell. Learn more about visiting our branches at Orange .

Service update:

Miramar Library will reopen at 2pm — maintenance related to last night's stormy weather is now complete. Thank you for your patience.

Service note:

Wadestown Library will close early on Thursday 12 August at 5:30pm for a community meeting.

Wellington City Libraries

Te matapihi ki te ao nui, te haerenga a ngā piringa pāka ki aotearoa i te tau 1981 the 1981 springbok tour of new zealand.

Other heritage topics

- Architecture |

- The sinking of the Wahine |

- Wellington waterfront |

- Earthquakes in Wellington |

- More heritage resources

The rivalry between the Springboks and the All Blacks is one of the longest and most enduring between two sporting nations. In the past, generations of rugby players and enthusiasts from both countries viewed a series victory over the other nation as being the pinnacle of achievement in the sport. Alongside the history of fierce competition went a tradition of hospitality towards the visiting side.

In 1956 and 1965 when the South African rugby team toured New Zealand, they were showered with warmth and generosity wherever they went. Yet 25 years later, the 1981 Springbok tour became one of the most divisive events in New Zealand history.

Its impact went far beyond the rugby ground as communities and families divided and tensions spilled out onto the streets and into the living rooms of the nation. What were the events that made this tour so significant? What motivated ordinary Kiwis to take such extraordinary action against one another?

Although things had been far from perfect between my parents, the Springbok tour caused such tension and stress that we could not live together in the same house and function as a family unit. An example of the increase was when we, as a family, watched the evening news. Often one side would raise their voices in abuse and offensive name calling towards public figures. Later the abuse was turned in an indirect way on individual family members. This was done by blaming the chaos and disruption to rugby games in individual family members, their friends and associations. As the tour went on and the turmoil increased, the negative feelings intensified to such as degree that feelings of dislike, anger and incomprehension dominated our home. It's Just a Game (anon), in, The New Zealand Experience : 100 Vignettes, collected by B. Shaw & K. Broadley, 1985 .

From Digital NZ

Central library closure — collection availability.

Unfortunately much of our heritage collection is currently not available through our online catalogue — because of the closure of the Central Library, much of this collection is in storage. We hope to make it available again soon, but in the meantime, we suggest visiting the National Library of New Zealand in Thorndon (Corner Molesworth & Aitken St) to access these book titles and newspaper resources.

- Visiting the National Library

- Using the National Library Catalogue

Newspaper articles

Unfortunately, contemporary newspaper accounts of the Springbok Tour from 1981 fall into a time period where newspapers are generally not even indexed for searching, let alone available in full text online — see our finding historical Wellington newspaper articles resource.

That being said, information about (and sometimes the full text of) many anniversary accounts (10 years, 20 years later etc.), can be found online (see Online databases below) — and contemporary accounts can be accessed on microfilm if you know approximate dates (we've provided a table of key dates below).

Finding Historical Wellington Newspapers

Tip: Remember that many reports will not appear in newspapers until the following day.

Magazines — online databases

Our online databases can also be used to access a large number of articles about the tour which have previously been published in magazines . Though the databases do not go back as far as 1981, they do contain many retrospective articles written since then.

- Magazine databases

- New Zealand databases

- Newspaper databases

To access contemporary accounts of the Springbok Tour in magazines, we recommend visiting the National Library on Molesworth Street (see collection note above).

To find magazine titles of interest, have a read of the article below:

Story — Magazines and periodicals in New Zealand

Heritage Links (Local History)

'Both countries learnt a lot' – Springbok remembers 1981 tour 40 years on

The third Test of the 1981 capped two months of civil unrest and division that left its mark on this country and South Africa.

Eden Park, regarded as the All Blacks' fortress for their dominant record there, actually looked like one on September 12, 1981. Flares smoked out the sidelines and flour bombs fell from a light plane buzzing the ground.

The third Test capped two months of civil unrest and division over the controversial Springbok rugby tour from apartheid South Africa.

The former Springbok captain Wynand Claassen remembers the game well. "That was bizarre. When you ran on to the field and that small plane circling, you know, I don't know how many times, somebody said about 110 times," Claassen said from his home in Pretoria.

But this was the series decider and the Springboks had a job to do.

"We couldn't bother about the plane because the All Blacks are a handful, so we've got to worry about the All Blacks and trying to win the Test," he said.

Keith Quinn commentated on the series. He said he found the Auckland match distressing as he watched the plane buzz the ground from the commentary box.

"My voice in the commentary is downbeat. It's not an upbeat commentary voice because I was anxious, if not scared, in some parts of that game," he said.

He also didn't agree with the tour going ahead and said so at the time. Consequently, the sports commentator was called "the enemy of rugby" by a top New Zealand rugby official. "I had been to South Africa in the 1976 tour and when I came home, I went on TV and said I would never go back to that place again."

Senior All Blacks from the 1981 tour declined or weren't available for interviews, not unlike 40 years ago. "We didn't hear much from the All Blacks on that tour. They were well looked after and there was a distance created," Quinn said.

He said he's since spoken to some All Blacks about 1981. "I think most of them were in favour of the tour."

The final match was narrowly won by the All Blacks, but it was overshadowed by the violence on the streets outside Eden Park.

It was the climax of weeks of demonstrations involving 150,000 people across 28 centres. Claassen said the Boks were not prepared for that level of opposition to the tour.

He recalled a news conference in Gisborne where he and other South African rugby officials got “hammered” with "not one rugby question". He said he thought they should have handled it differently. "We should have been open about South Africa and the problems we had," he said.

The protests also highlighted problems in New Zealand. Donna Awatere Huata was a member of the Patu squad, an anti-tour group led by Māori activists that aimed to put the spotlight on racism at home.

"And to that end we were partly successful. Not totally but we did make some gains," said Awatere Huata. She said gains were made shortly after the tour in education and the police, but "by and large they were very small”.

"The legacy of the tour is that we have a long way to go. We made a minor dent in the colonial attitudes but what we are left with now is still a colonial bureaucracy, a colonial government that still hasn't made the changes that need to be made to honour the Treaty," she said.

In South Africa, the 1981 protests put the pressure on for political change. Claassen said it marked the "beginning of the end" of apartheid.

He sees the tour as a part of history. “It’s a strange way of looking at it, but we were. Both teams, both countries… I think both countries learnt a lot from each other.”

More Stories

Newsmakers: John Minto looks back at 1981 Springbok tour protests

Minto helped plan demonstrations that saw 150,000 people take to the streets around Aotearoa.

Sat, Apr 13

Education Ministry staff anxious over 'uncertainty' of job cuts

RNZ understands some people at the Ministry of Education have already been told they are affected by the cuts.

'Corrosive obsession with a person's race': David Seymour on Māori Wards

Fri, Apr 12

'I know how that feels' - Minister tears up during campaign launch

Trans woman Paipera Hayes on being a lead actress

Govt reveals targets — including 50k people off benefit by 2030

More farmers' cows in Taranaki grazier's care go missing

Sydney cop rushed to Bondi mall, learnt fiancée was a victim

'Out of character': Bondi killer's mum speaks, apologises to public

Aus political official raped colleague, loses defamation case — judge

'Loving a monster': Bondi killer's dad speaks out

Jenny-May Clarkson reveals her moko kauae: 'This is still me'

Sunday 1:45pm

First look: NZ’s first large-scale dam built in the last 30 years

Singapore PM steps down after Luxon meeting, PM pays tribute

Middle East casts shadow over Luxon's trade trip to SE Asia

Trump hush money trial to start tomorrow with jury selection

Online watchdog urges public not to share images of Bondi attack

Renowned Kiwis open up about their personal mental health in new series

Sponsored by AIA NZ

More from Entertainment

Ne-Yo to play one-off show in New Zealand

The Grammy award-winning singer has announced he's bringing his Champagne and Roses tour to New Zealand.

'Most magical place on earth': SZA praises NZ at sold-out show

The 34-year-old is in New Zealand for three shows on her SOS tour.

Sunday 4:00pm

'I love this country' - Momoa pays tribute to NZ as filming wraps

Netflix show drives tourists to stunning Italian village

Taylor Swift back on TikTok in time for new album's release

Splore festival to take 2025 off after 'challenging' season

- Home Kāinga

- Our Story Ngā Kōrero

- Our Tours Ngā Haerenga

- Wellington Museum Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Space Place Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Nairn Street Cottage

- Cable Car Museum

- Careers Umanga

- What’s On Ngā Kaupapa Whakatairanga

- Museum Blog

- Our Venues Ngā Wāhi

- Venues at Wellington Museum Ngā Wāhi i Te Waka Huia o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Ara Whānui ki te Rangi

- Birthday Parties Ngā Pāti Rā Whānau

- Recommended Caterers Ētahi Kaitaka Kai

- Education Blog Rangitaki Mātauranga

- Space Place

- Wellington Museum

- Space Place Wāhi Haumaru

- Venues at Space Place Ngā Wāhi i Te Wāhi Haumaru

- Support Us Tautoko

- Museum Blog Te Kāpata Te Curio

Remembering the 81′ Springbok Tour

40 years on, we look back and talk to two Wellington residents who remember those turbulent times.

“All for the sake of a Rugby game. Doesn’t make sense does it?” – Liz Roberts

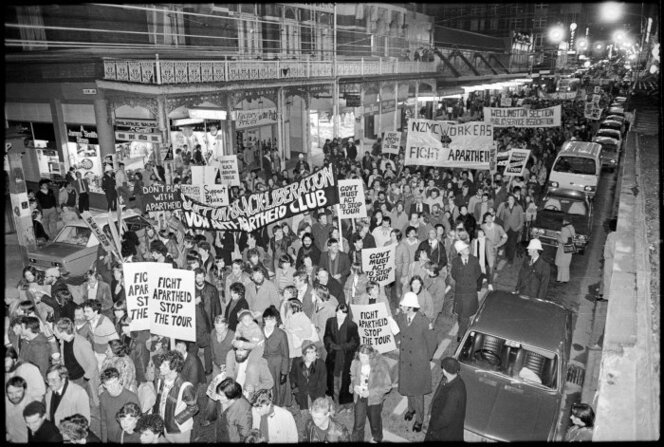

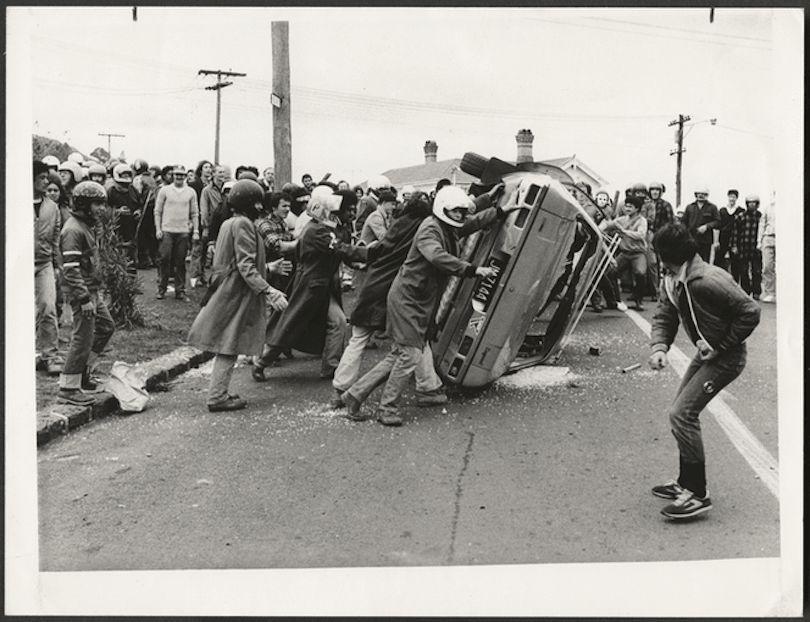

During the winter of 1981, violent clashes between rugby supporters, protesters and the police erupted all over Aotearoa in one of our country’s most tumultuous periods. The Springbok rugby tour brought us to the brink of civil war, as many protested the racial segregation of Apartheid South Africa and made links to racism at home.

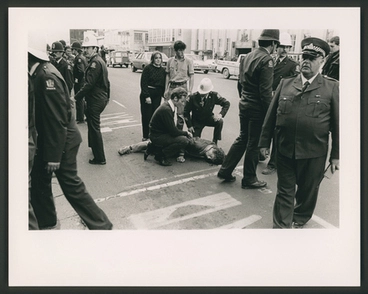

On the 29th of July, 1981, protesters opposing the Springbok Tour were met by baton-wielding police trying to stop them marching up Molesworth St to the home of South Africa’s Consul to New Zealand.

This was the first time police had used batons against protestors, and the violence horrified many New Zealanders. Former Prime Minister Norman Kirk’s prediction eight years earlier that a tour would result in the ‘greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known’ seemed to ring true.

Wearing helmets like this one, 7000 protesters gathered in central Wellington and around Athletic Park on 29th of August 1981 to stop pro-tour supporters from gaining access to the second test match. Once again the police intervened, this time using long batons, with many protesters injured as a result. This helmet was worn by Anne Bogle during other anti-tour protests.

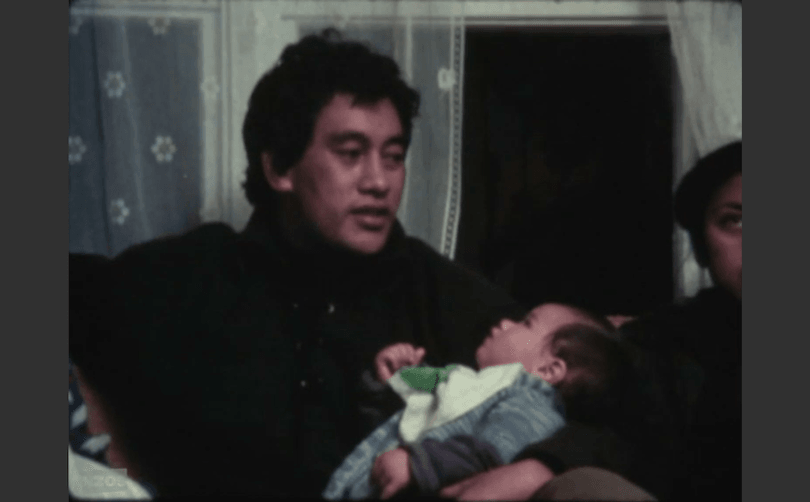

The Merata Mita Estate permitted us to use the Wellington footage from PATU! (1983) – the powerful documentary directed by Merata Mita which shows the harrowing events of the 1981 Springbok Tour.

Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision meticulously restored and preserved the original documentary for the 40th anniversary. With their approval, we were able to use their newly restored and remastered version for these videos.

Liz Roberts lived on Te Wharepōuri Street in Berhampore, close to Athletic Park, and recalls the events of the 2nd Test on August 29th, 1981, where she saw protesters clash with Police on her street.

Anne Bogle was a young Victoria University student studying Law and History in 1981 – and attended a number of Anti-Tour protests in Wellington – she took part in the protest group that blocked the Wellington Motorway on July 25th and the infamous Molesworth Street incident a few days later on July 29th. The protester helmet she used during the anti-tour demonstrations is currently displayed at Wellington Museum.

Thank you to the Merata Mita Estate for their permission to use parts of the film and also to Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision for their great mahi on the preservation and restoration of this important piece of film taonga .

Also thank you to Anne Bogle and Liz Roberts for sharing their stories.

Pin It on Pinterest

Springbok tour protest at Hamilton, 25 July 1981

A DigitalNZ Story by Zokoroa

On 25 July 1981, anti-tour protesters led to the Springbok - Waikato rugby game being halted in Hamilton

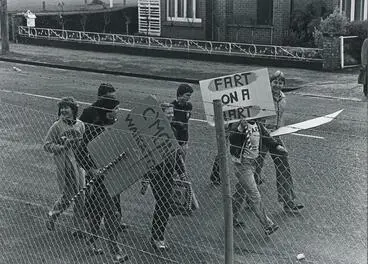

Rugby , Sport , Springbok , Springboks , Hamilton , Anti-tour , Protests. Apartheid , Anti-apartheid , Racism , Anti-racism , HART , Politics

In 1981 the Springbok rugby team toured New Zealand which led to public protests. Those against the tour objected to South Africa's apartheid policies, whilst those supportive of the tour thought politics and sport shouldn't mix. The game against Waikato at Hamilton's Rugby Park on 25 July was called off when several hundred anti-tour demonstrators invaded the field. During the clashes between pro-tour and anti-tour supporters, over fifty arrests were made. The tour also led to debate about racism and the place of Māori in New Zealand.

Two members of St John's College run onto Rugby Park, Hamilton, while two supporters of Springbok Rugby Tour try to stop them, 1981

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

"Confrontation on Centre Field" - 1981 Springbok Tour

Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato

Protesters in Hamilton during a demonstration against the 1981 Springbok tour - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Alexander Turnbull Library

National protests

Protest badges - 1981 Springbok tour

Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Stop the tour

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

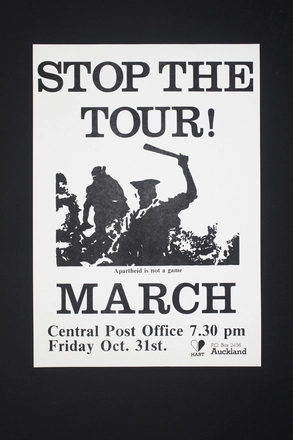

Springbok Tour protest programme

Poster was published by HART (Halt All Racist Tours) and handed out to anti-apartheid activists

Poster, 'The 50 Guilty People'

'No Tour' T-shirt

July petition to PM Robert Muldoon calling for the Springbok rugby team to be refused entry into NZ

Petition Cards to Robert Muldoon

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

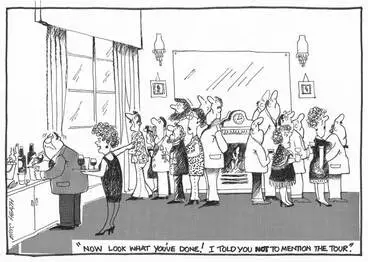

'Don't mention the tour'

Waikato stadium, hamilton: 25 july 1981.

Hamilton's rugby wars - Roadside Stories

Demonstrators Handbook

Protestors lined up across road. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Photograph - 1981 Springbok Tour

Members of St John's College before march to Rugby Park against Springbok Rugby Tour, Hamilton, 25 July 1981

![[Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre] Image: [Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2Fcb169b4cfd2233f12df791c5af4ba06bc4470a1d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Christian protesters sing in an outdoor shopping centre]

Photograph – Springbok tour protest

Protesters hold anti-apartheid and anti-racism signs

Fence, Hamilton

Group of protestors middle of rugby field with spectators behind. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Group of protestors including Geoff Chapple in middle of rugby field. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

![[Protesters occupy a rugby pitch] Image: [Protesters occupy a rugby pitch]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F12c490904f98340761e6a8bf5f035e791d6df33d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Protesters occupy a rugby pitch]

Policemen in riot helmets standing on Rugby Park, Hamilton, during the Springbok rugby tour - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

"Rev. George Armstrong (St. Johns College, Auckland) pleading with Riot Squad" - 1981 Springbok Tour

Line of police confronting protestors. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

"Riot Squad on rugby field" - 1981 Springbok Tour

![[A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton] Image: [A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F40cb0fdb2ef59bfbe1b9e1a93fd27d5ebf48b618%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[A police line and protesters face off on the rugby pitch at Rugby Park, Hamilton]

Police and tour protesters on Rugby Park, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Baton used by two special police squads formed as security escorts for Springboks

PR 24 baton

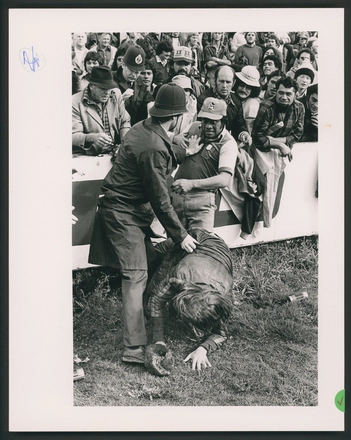

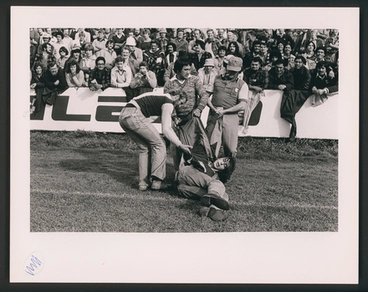

Protestors and police officers at Rugby Park, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Phil Reid

Hamilton, 25 July

Police confronting protestors on rugby field. Anti Springbok Tour protest march, Hamilton

Police separating demonstrators & rugby Fans Hamilton.

Police struggle with demonstrators, Hamilton - Photograph taken by Ian Mackley

Rugby supporters hand a demonstrator off the Field, Hamilton.

A demonstrator lies bloody unconscious in Victoria St, Hamilton.

![[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton] Image: [Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F850aa51c4f15738b036acfa8730c91ebbc69b21d%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]

![[Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton] Image: [Proof sheet - Springbok tour protest Hamilton]](https://thumbnailer.digitalnz.org/?resize=770x&src=https%3A%2F%2Fmedia.api.aucklandmuseum.com%2Fid%2Fmedia%2Fp%2F92d515aa64923b96854a7fdfe70fcdde07a4a9d3%3Frendering%3Dstandard.jpg&resize=368%253E)

This calendar was produced in 1982 to raise legal funds for protesters who had been arrested during Springbok tour

Days of Rage calendar

Reaction in south africa.

The Waikato game was the first being televised live back to South Africa, so viewers there saw the NZ opposition to the tour and apartheid.

Try Revolution

NZ On Screen

Bromhead, Peter, 1933- :'Right Jan...you on the vickers..and the other nineteen pick up the bodies...' Auckland Star, 28 July 1981.

1981 springbok captain recalls impact of pitch invasion.

Radio New Zealand

Personal accounts

After the tour, English Department of University of Canterbury placed adverts to gather people's comments & experiences

Springbok Tour Archive [Pro]: Hamilton group on democracy versus communism.

University of Canterbury Library

John Minto, national organiser of Halt All Racist Tours (HART), looks back on the 1981 Springbok tour

John Minto - 1981 Springbok tour

Blazey discussing the 1981 springbok tour, stories told about violence : hamilton during the 1981 springbok tour / by nikita prinsloo.

National Library of New Zealand

Springbok Tour Archive [Anti]: Hamilton woman's note on experience and feelings during the tour.

Springbok tour archive [anti]: coromandells housewife's account of trip to hamilton and repercussions., springbok tour archive [pro]: hamilton person, 60. nz freedoms, protest activity, anti-authority elements., springbok tour archive [anti]: christchurch middle-aged man discussing maoris and racism., springbok tour archive [pro]: a northland woman's views on communism, professional 'stirring', hamilton match, violent protest etc., video / audio.

1981 - A Country at War

Waikato game stopped, 1981

The game that never was

Film: game cancelled in hamilton, 1981 springbok tour, hamilton's rugby wars - roadside stories, report on protests at rugby park.

Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

Anti-Springbok-tour veterans on the power of HART

Books / articles.

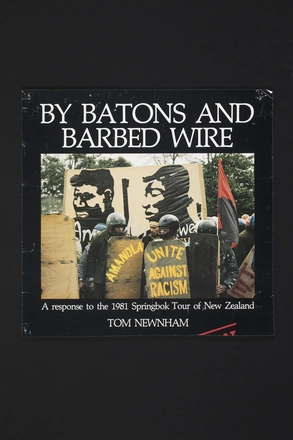

By batons and barbed wire

Roadside stories: hamilton's rugby wars, anti-springbok protesters block hamilton match.

(This DigitalNZ Story was compiled in 2020)

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour

Coverage of the game and the protest actions

Collection items

The vault - 1981 springbok rugby tour.

Flour bombs, flares and leaflets were dropped from a low flying Cessna plane which buzzed the third and final game of the 1981 Springbok Tour - dramatic Radio New Zealand coverage of the game and the… Audio

- Download as Ogg

- Download as MP3

- Play Ogg in browser

- Play MP3 in browser

Access All Areas: A Country Divided

The winter of 1981 saw the Springboks rugby team tour New Zealand, and Kiwis divided. Recent Maori attempts to reclaim ownership of government requisitioned land at Bastion Point had focused attention… Audio

This audio is not downloadable due to copyright restrictions.

Anti-tour protestor reflects on thirty years since first game

Thirty years since the first game in the 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand. Audio

Brian Morris remembers the 1981 Springbok Tour

Ngāti Kahungunu Rongowhakaata Brian Morris was a Hawkes-Bay-representative-rugby-playing-school-teacher in 1981 when he made a stand against apartheid and the Springbok tour. He talks about that… Audio

Tom Scott: Rage

Tom Scott is a cartoonist, satirist, author and playwright. His latest project is a television docu-drama centred on the controversial 1981 Sprinkbok tour of New Zealand. Rage is the story of two… Audio

Springbok Tour put NZ Commonwealth Games in danger

Confidential Australian cabinet papers from 30 years ago, which have just been made public, reveal that concern about the 1981 Springbok tour was so high, it jeopardised New Zealand's participation at… Audio

New Zealand As It Might Have Been: Bob Gregory

What would have happened if New Zealand had lost the last test against the Springboks during the troubled tour of 1981? Bob Gregory, a professor of politics at Victoria University of Wellington… Audio

External Links

- The tour on NZ History Online

- The 1981 Springbok tour at Te Papa

- Patu! : Merata Mita’s documentary about the winter of 1981 on NZ On Screen

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Rugby, racism and the battle for the soul of Aotearoa New Zealand

The Springboks’ tour and the protests that ensued 40 years ago helped set the fight for Māori rights on a stronger path

The 1981 Springbok rugby tour of New Zealand will always have a special place in any narrative about the international fight against apartheid in South Africa.

The protests against the Springboks reverberated around the world – delivering a savage psychological blow to South Africa’s white regime while giving a resounding boost to the oppressed majority.

This weekend marks the 40th anniversary of the first rugby Test of the Springboks’ tour of New Zealand in Christchurch, but well before that game was played, the political significance of the visit had eclipsed any results on the field.

Three weeks before the first Test, the second game of the tour was to be played in Hamilton, and white South Africans in their droves got out of bed in the middle of the night to watch the first ever live telecast of a rugby game in the country.

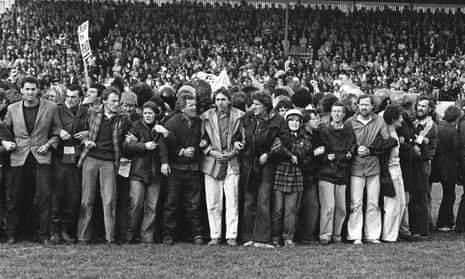

It was to be a special moment in South Africa, but not as expected. Instead of the Springboks vs Waikato game, fans saw 300 protesters linking arms in the middle of Hamilton’s Rugby Park – declaring they would not leave till the tour had been called off.

The anger that swept through white South Africa was nearly as palpable, if not as physical, as the anger expressed on Hamilton’s streets in the ensuing hours.

On South Africa’s Robben Island, Nelson Mandela was spending his 18th year in jail. He said when the prisoners learned that an anti-apartheid protest had stopped the game, they were jubilant. They grabbed the bars of their cell doors and rattled them around the prison; he said it was like the sun came out.

Here in Aotearoa New Zealand, the tour protests also had a profound impact, although this took longer to play out. It was the closest we had come to civil war since the 19th century land wars, but more importantly the tour shone a harsh spotlight on racism in this country. Māori activists asked how could we be concerned about racism 10,000km away and ignore it in our own backyard? Fair question.

In the aftermath of the tour, racism took centre stage with an intense public debate that helped set Aotearoa New Zealand on a new path.

A decade earlier, Māori activist groups like Ngā Tamatoa (the young warriors) had challenged the Pākehā (European) majority about patronising attitudes and lazy racism that meant Māori were in effect second-class citizens.

Politicians are slow followers of public opinion, but four years after the tour and the wide discussion and debate it helped spur, the Waitangi Tribunal was given the responsibility to investigate historic breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi – previously the tribunal had only been mandated to look at possible future breaches. And so began its investigations into our history of racism and oppression and the injustices of colonisation, which continue to resonate for Māori in the present.

Since then numerous positive developments have given a stronger political voice to Māori.

In our most recent budget, the health minister, Andrew Little, announced the formation of a national Māori health authority that will have the power to contract health services for Indigenous New Zealanders where the state system has served them poorly. “By Māori, for Māori” is seen as a way to enhance our democracy with a turn away from the “tyranny of the majority”, under which they have fared poorly.

It’s not all plain sailing though, and recent debate about Māori rights to representation on local councils has met hostile, albeit minority, opposition.

But the direction continues to be forward and work is under way to incorporate the history of colonisation in these South Pacific islands into the school curriculum.

The irony in these positive developments is that the overall situation for most Māori is getting worse, with New Zealand’s Indigenous people disproportionately affected by poverty and inequality, which continues to grow relentlessly with the pandemic.

The civil disruption from the tour and the debate that followed benefited both New Zealand and South Africa in ways that we didn’t see at the time. We are a better country for it.

John Minto was national organiser of Halt All Racist Tours (HART) in 1981 and is currently the national chair of Palestine Solidarity Network Aotearoa.

- New Zealand

- Asia Pacific

- Rugby union

Most viewed

- Access Statement

- Community Archive

- Family History

Sir Michael Fowler

- Molesworth Street

- Related Items (9)

- Related Items (5)

- Related Items

- Property Search

- Archives online user guide

"I hope that common sense will prevail." – Sir Michael Fowler, Mayor of Wellington, 28th August 1981 From 22 July – 12 September 1981 the South African Rugby Union team (known as the Springboks) toured New Zealand playing 14 games. Due to the South African governments policy of apartheid, the tour was marred by protests and police violence. The All Blacks and the Springboks had been fierce rivals since their first face-off at Athletic Park in 1928, and rugby had since become New Zealand’s national identity. But at the same time, South Africa’s system of racial apartheid had grown unacceptable to many people in New Zealand and overseas. Wellington was a focal point for much of the anti-tour movement during 1981 tour. The Mayor and many of the City Councillors came out against the tour, and several attempts were made by Council to prevent a test match in the City. Protesters clashed with police during a protest on Molesworth Street leaving many battered and bloody. When they next met outside Athletic Park on the day of the test, the protesters came prepared with helmets and shields. The Springboks left New Zealand following their final game in Auckland and would not return until 1994 and the dismantling of apartheid. Linked below are photos of anti-tour posters and pamphlets taken by the City Photographer, as well as a considerable amount of correspondence to and from Mayor Fowler via the Town Clerk's Department. The featured minute book contains City Council meetings related to the tour on pages 207-208 (images 286-287) and 221-222 (images 300-301).

Copy: Abortion, Apartheid, Unions, Nuclear (posters, handouts, protests)

Notice of motion: Springbok Rugby Tour, REDACTED

Volume 102, REDACTED, Minutes of meetings of the Wellington City Council 5 Jun 1981 to 11 Nov 1981

The Spinoff

Ātea December 28, 2021

Three things you didn’t know about the 1981 springboks tour.

- Share Story

Summer read: This year marked the 40th anniversary of the rugby tour that divided a nation. While countless books and articles have been written about that time, some important details have faded with age. Leonie Hayden looks back at three of them.

First published July 22, 2021

Merata Mita’s documentary Patu! opens with a group collecting signatures on the street in Auckland to petition the government to stop the upcoming Springboks’ tour of New Zealand. A young passer-by starts arguing with the organisers, asking how would they feel if a group of “wogs” or “Blacks” came over here. One group member explains that she’s married to a Black South African man. Undeterred, the man continues his tirade about what would happen if “they” were in charge.

It’s 1981 and Mita’s grainy film footage captures one of those most divisive periods in our history since the New Zealand Wars. It was a battle that played out on the rugby field, in the streets, within the halls of parliament and at kitchen tables all over the country. But the fight for New Zealand to take a stand against South Africa’s apartheid regime was far from new.

The New Zealand Rugby Football Union had left rugby legend George Nēpia and other giants of the game at home in 1928 to conform with South Africa’s segregation laws. In 1959, the Citizens’ All Black Tour Association had tried to demand “No Maoris, no tour” when Māori players were excluded from the team’s 1960 visit. They weren’t successful then, but Māori players would go on to tour South Africa as “honorary whites” in 1970 and then in 1976 – the same year as the Soweto uprising that saw hundreds of children and student protestors murdered by police.

While Robert Muldoon campaigned on sports and politics being kept separate, deftly side-stepping the Commonwealth members’ Gleneagles agreement , the world had very much decided the two were connected. Black African nations boycotted the 1976 Montreal Olympics in protest of our ongoing engagement with South Africa. New Zealand was becoming a pariah.

And so when the 1981 tour was announced, anti-apartheid groups such as Halt All Racist Tours (HART), Citizens Association for Racial Equality (CARE) and the Patu Squad (led by Hone Harawira, Donna Awatere, Josie Keelan and Ripeka Evans) began a national campaign to stop it in its tracks.

Ultimately, the demonstrations and petitions to Muldoon’s government – plus a national poll showing only 46% public support for the tour – fell on deaf ears and the South African team were officially welcomed to New Zealand at Te Poho-o-Rawiri marae in Gisborne on July 19, 1981.

Tā Graham Latimer’s wero

It was a pōwhiri with teeth.

The welcome for the Springboks took place at the same time as Māori activists were spreading glass across Gisborne’s Rugby Park ahead of the first game. The speakers that evening comprised Te Poho-o-Rawiri kaumātua, dignitaries of the Tairāwhiti Māori council, and the president of the New Zealand Māori Council, the late Sir Graham Latimer .

To many the welcome would have looked like a sign of a generational divide – conservative assimilationists on the marae versus activists on the field – but Latimer ensured the pōwhiri wasn’t an occasion that ignored or played down what was at stake. In fact, he very politely told Springboks captain Wynand Claassen and his team they wouldn’t be welcome again while apartheid remained in South Africa.

Per tradition, it was Latimer’s role as the New Zealand Māori Council president to extend a greeting to any international group being welcomed onto a marae. The speaker before him, Tom Fox, had emphasised with some pride, and to much applause, that the Tairāwhiti branch was the only Māori council that actively supported the tour.

Latimer, however, was less effusive. “I am fully conscious of the fact that I do not have a complete mandate to make this welcome,” he began. “Seven out of the nine district councils that make up the New Zealand Māori council are opposed to the tour, and one is undecided.” A long pause, silence from the crowd.

“Fifty-four per cent of the general public of New Zealand has expressed opposition to your tour. That’s in a poll. The last time such a tour was mooted, only 16% were against the tour. That you have come has been seen by some as a major victory but it must be recognised that if there were only another 6% against the tour, there would be neither a political party not a rugby union game enough to extend an invitation to you.”

He continued: “There can be no doubt in my mind that we will not be making another such welcome on a Māori marae – I emphasise that point – unless your government can show it is prepared to change its policies on apartheid. We hope we can look forward to a time in the not too distant future when you could be welcomed on any marae. It would be a pity if this could be looked upon as the last international tour by South Africa.”

Latimer finished by giving an especially warm mihi to Errol Tobias, the first player of colour to tour with the Springboks. “I believe he represents hope for 18 million South Africans, for whom there appears to be little hope.”

The genius of Latimer’s challenge was in its statesmanlike delivery. While much of his speech was received with (presumably) shocked silence, he was still rewarded with a huge round of applause at its conclusion, even though he had just told those gathered they would not be welcome in future under the same circumstances. The extraordinary recording of that evening, housed in the Ngā Taonga archive , captures a mild-mannered assassin executing an entire squad with diplomacy.

Naturally we have no way of measuring the effects of that speech on either the Springboks or apartheid. But it may have been the last time the issue was discussed politely.

Police violence was far worse than they’d like you to remember

Nicknamed the Day of Shame, July 22 saw the Springboks’ opener against Poverty Bay. Three hundred protestors marched to Rugby Park in Gisborne via a nearby golf course and attempted to breach a fence. Rugby fans jumped into action and a brawl broke out between the two groups. Police arrived to break up the fighting, and only two men managed to run onto the field. Thirteen were arrested and many were hurt in the resulting brawl, but it was nothing compared to the violence that was to come.

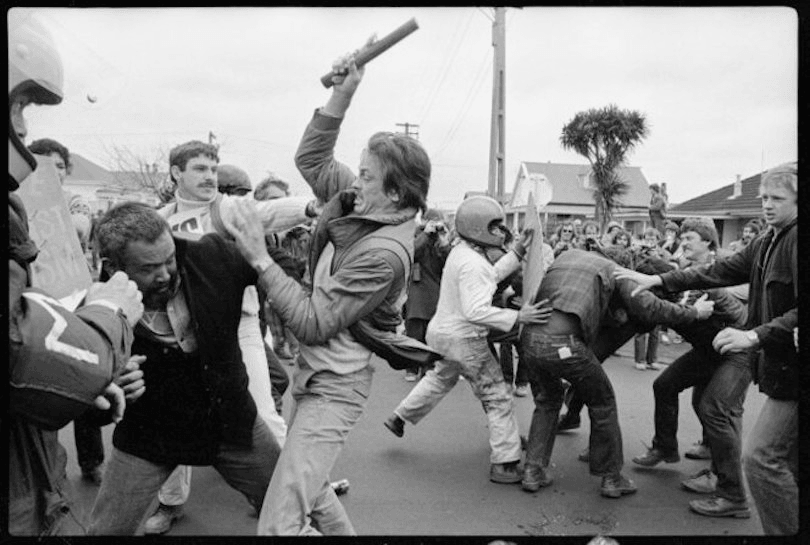

Over the course of the next two months, police, in particular the infamous Red and Blue riot control squads, would become more and more comfortable with using extreme violence against unarmed protestors, causing serious and sometimes permanent injuries. Pro-tour rugby fans were also brutal in their retaliation.

Singer and journalist Moana Maniapoto, then a first-year law student at the University of Auckland, remembers when the fence came down at the second game in Hamilton on July 25. “Everyone’s leaning on it, pushing and pushing it, and then the next minute the fence came down and you just heard this ‘Run!’ You’re just swept along. So then I’m in the middle thinking, ‘what am I doing here? They’re gonna kill us!'”

She recalls looking up at thousands of angry faces in the stands. “They were totally rabid. Screaming, yelling and throwing cans of beer at us.

“The police arrived, just the ordinary cops, not the Red Squad, and I actually thought, ‘oh this is good, surely they’re not gonna let us get murdered’. Then the commissioner came on and said the match has been called off and there was this huge roar from the crowd. At first it was like, ‘yay!’ and then ‘oh my god. How the hell are we gonna get out of here?’”

Maniapoto, along with land protector Eva Rickard and another friend, managed to escape into the surrounding streets. “The cops were sporadically placed so you had to make a run for it to the gate. Then the cops recognised Eva and they were abusing the shit out of her. But we got out, and we were very lucky, my friend’s father heard on the radio that the match had been cancelled and he circled until he found us. A lot of people got attacked.”

Marx Jones and Grant Cole flour bomb Eden Park in a hired Cessna.

She would go on to attend protests in Rotorua and at the third test in Auckland – the latter resulting in a violent clash between police, protestors and rugby fans on the streets of Mount Eden. “Red Squad came out of nowhere and nutted off at everyone. I was with the least militant bunch when they charged. We were just standing there. Couldn’t believe it. I was batoned, kicked by heavy police boots while on the ground. Shock for a young freshie like me. They just smashed into us and left people lying on the ground in their wake.”

For further proof you need only watch the violence through Mita’s lens. The dull thud of police batons hitting flesh and human skull, and the wails of the injured, some of them young teenagers, is the haunting soundtrack for nearly half the film.

Maniapoto scoffs at the selective memory that it was “New Zealand” who took a stand against apartheid. “It’s held out as a landmark, framing New Zealand as a global social justice advocate. It wasn’t New Zealand; it was people power. It was activists, people from across all walks of life, and there were far fewer of us than there were in the stands.”

She talks abut the Nelson Mandela exhibition hosted at Eden Park in 2019 – a strange venue considering the violence that played out on the surrounding streets 38 years earlier. She says at the launch none of the speakers from the New Zealand Rugby Union came close to admitting they’d been wrong, or offering an apology. Instead everybody spoke proudly about the stand taken by the protestors. Says Maniapoto: “They’re starting to rewrite the history!”

The good bishop saves the Patu Squad

It was at the last test at Eden Park on September 12 that a young Hone Harawira, one of the leaders of the predominantly Māori and Pasifika Patu Squad, was finally caught.

Harawira and a handful of others had been arrested at Waitangi earlier in the year, and although they had been denied bail, they were turfed out of the cells for causing a ruckus and told when to attend their court date. They didn’t show up.

The group had outstanding warrants for their arrest before the tour even began.

“It must have got out to the police that we were all going to be involved in the tour, and one by one we were all picked up. One of the brothers, they got him before it started! So he spent the whole of the tour in Mt Eden,” Harawira chuckles.

Harawira says he was caught early on after the test that ended with Marx Jones’ aerial flour bomb attack , so hadn’t been involved in the upturning of a cop car, or the violence that erupted on an unprecedented scale outside Eden Park. Nevertheless, Harawira was charged with the assault of a police officer who’d had both collar bones broken.

“It wasn’t me but they wanted someone to pin it on so they pinned it on me.”

He says he had seven charges against him. “They were serious charges. Three charges of participating in a riot and four charges of assault with intent to cause grievous bodily harm. Which all carried a total of something like 98 years.”

Justice being neither blind nor in a hurry, Harawira wouldn’t stand trial for another two years, alongside many others who he notes were mostly brown, despite the vast majority of protestors being Pākehā. “Most of them were members of the Patu Squad.”

As he had many times before, Harawira planned to defend himself in court. He’d had University of Auckland law lecturers Jane Kelsey and David Williams to rely on for advice, but this time he wasn’t sure it going to be enough.

“The day before my court date, I’m sitting out the back in the cells thinking ‘jeez, what am I gonna do?’ Then the brain wave came to me. Bishop Desmond Tutu had been invited over by the Anglican church to come and do a speaking tour. Interest was still very high in apartheid South Africa. My mum knew George and Jocelyn Armstrong, who were part of the organisation that brought him over.

“So I rang my mum and said look, I want Bishop Tutu as a witness. She said, ‘He wasn’t there!’. I said, ‘that doesn’t matter! I want him for my witness’. So she said ‘OK when is it?’ And I said ‘Tomorrow! I’m gonna need him by about 10.30.’”

The next day Harawira and 10 others prepared to stand trial.

When the time came for him to give his defence, his star witness wasn’t there. “I read my statement. I’d come to the very end and I was dragging it out. I didn’t want to get out of the dock ‘cos I knew it hadn’t been enough to get me off. Then the door burst open, and someone looked at me with a big smile and just nodded and I knew then. So I asked the judge: ‘Can you please call my witness?’”

Harawira still laughs at the memory of the stunned faces of the judge, prosecution and jury as as the now-Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in his signature dark suit and purple cleric’s shirt, walked into the courtroom.

“And then I’m thinking, ‘What the fuck, now what do I do?’

“So he takes the stand and I go, ‘Could you please tell the court your name?’ And then I said, ‘Can you please tell the court your address?’ And he gave an address in Soweto. Instantly, if the room wasn’t already charged, everyone was completely wide-eyed now.

“And then I said, ‘Can you please explain to the court what apartheid is?’. And away he went. He must have spoken for 20 minutes. It was absolutely stunning. You could have heard a pin drop.”

He says that after Tutu had finished, neither he nor the prosecution could think of any more questions.

“As Bishop Tutu stepped out of the dock, all 11 defendants, we all stood up. Then our lawyers stood up, then the public, the screws from Mount Eden, the police stood up, then the jury stood up. Half of them were in tears. If was one of those moments. I knew right then and there we were gonna get off.” He crows in delight at the memory.

The group were acquitted of all charges.

“It’s kind of hard to believe but it’s all true. Meeting Nelson Mandela himself and going to his tangi, that’s another story.”

We are here thanks to you. The Spinoff’s journalism is funded by its members – click here to learn more about how you can support us from as little as $1.

- New Zealand Heritage List

- Nominate and submit

- Explore the List

- Rainbow List Project

- Lost heritage

- National Historic Landmarks

- Turnbull House Project

- Visit Heritage

- Our properties

- Collections

- Tohu Whenua

- Conserving Māori Heritage

- Marae built heritage

- Māori heritage on the List

- Archaeology

- Archaeological authorities

- Digital Library

- Declaring an archaeological site

- Publications

- Sustainable management guides

- Disaster recovery

- Podcasts & digital resources

- Conservation plans

- Māori Heritage Council

- Senior Staff

- Covid-19 response

- Corporate documents

1981 Springboks vs Waikato

By Niki Partsch

Winter weather had little to do with the famous cancellation of a Springboks vs Waikato rugby match 42 years ago.

Before the digital era, an international game of rugby anywhere involving the All Blacks would empty shops, businesses and roadways, and for a golden hour and 30 minutes our country would look almost deserted as all eyes and ears turned towards TV screens and radios.

Despite the presence of 535 police officers at the 1981 Hamilton game, a throng of everyday New Zealanders opposed to the tour, managed to get onto the rugby pitch to prevent the game taking place and forcing the now historic cancellation. This caused annoyance and anger amongst the many other everyday New Zealanders who wanted to watch the game. The ensuing ruckus which unfortunately deteriorated to violence created further divisions amongst New Zealanders.

At the heart of the issue was the policy of apartheid in the home country of the touring team, South Africa.

Apartheid, which translates to ‘apartness’ in Afrikaans was a racist system of legislation crafted to uphold the segregation of non-white citizens in South Africa. All citizens were sorted by racial categories of white, black, coloured, or Indian/Asian. With white South Africans effectively holding power at the expense of all others, this legislation was unsurprisingly unpopular amongst non-whites. As the anti-apartheid movement there grew, so did support from many New Zealanders. That support included protests of the 1981 Springboks tour.

"I’m glad I went and believe I played a part in undermining apartheid in South Africa by being Māori and not signing on as an 'honorary white'"—Billy Bush (1976)

Amid this highly contentious 1981 test series and tour of New Zealand, communication between groups was often poor. Many took a firm stance about not mixing sport with politics, for others it was simply unconscionable to invite representatives of a racist regime over for a tour, a situation exacerbated by knowing that only white players would be included in the team.

The fallout was widespread across communities, families and businesses. Sides were taken and relationships significantly challenged. While some agreed to disagree, feelings often ran deep and so divisions grew. Bizarrely, some people who previously agreed on nothing at all, were suddenly brothers in arms. Families and work colleagues divided themselves into for and against factions and some couples filed for divorce.

Bill Bush (Ngāti Hineuru and Te Whānau ā Apanui) was equally hailed and reviled for taking part in the earlier 1976 All Blacks tour of South Africa. His reasons for going were not well known at the time, but he later wrote in his book, Billy Bush: A Front Row View on Life written by Bill Bush with Phil Gifford. “At the time I was selected for the 1976 All Blacks tour of South Africa I found the whole idea of apartheid abhorrent, but I wasn’t fully aware of what was going on there, so even though I suspected our tour would be a disturbing and unsettling experience in many ways, I still wanted to go.”

He indeed had many unsettling experiences during the tour and was the recipient of strong criticism from home but also wrote, “I have no regrets, even though the Springboks won the series 3–1. I’m glad I went and believe I played a part in undermining apartheid in South Africa by being Māori and not signing on as an ‘honorary white’ as All Blacks in 1970 had to.”

Related articles

Stay up to date with Heritage this month

1981 Springbok Tour

First major demonstration, springboks arrived in new zealand, first rugby test.

Protesters attack Rugby Park in Hamilton

Hamilton Game Cancelled

Anti-tour protest in molesworth street in wellington.

First Test in Christchurch

Second Test in Wellington

"Flour-bomb" test in Eden park in Auckland

Springboks leave new zealand.

New Zealanders protest against Springbok rugby tour, 1981

Time period, location description, methods in 1st segment, methods in 2nd segment, methods in 3rd segment, methods in 4th segment, methods in 5th segment, methods in 6th segment, additional methods (timing unknown), segment length, external allies, involvement of social elites, nonviolent responses of opponent, campaigner violence, repressive violence, classification, group characterization, groups in 1st segment, success in achieving specific demands/goals, total points, notes on outcomes, database narrative.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART) was organized in New Zealand in 1969 to protest rugby tours to and from South Africa. Their first protest, in 1970, was intended to prevent the All Blacks, New Zealand’s flagship rugby squad, from playing in South Africa, unless the Apartheid regime would accept a mixed-race team. South Africa relented, and an integrated All Black team toured the country.

Two years later, the Springboks arranged a tour of New Zealand. HART held intensive planning meetings, and, after laying out their nonviolent protest strategies to the New Zealand security director, he was forced to recommend to the government that the Springboks not be allowed in the country. Prime Minister Kirk, though he had promised not to interfere with the tour during his election campaign, canceled the Springbok’s visit, citing what he predicted would be the “greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known.”

HART remained active in the anti-apartheid community, continuing to protest the Springboks, and helping to organize a boycott of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. The International Olympic Committee had not banned New Zealand after the All Blacks had toured South Africa, and many African countries saw this failure as a tacit endorsement of Apartheid. In 1980, New Zealand again attempted to bring the Springboks to New Zealand.

The Springboks arrived on July 19, 1981. Though they were officially welcomed by the New Zealand government, there was a sense of dread and anticipation that surrounded their arrival – perhaps, some thought, the 1981 tour should have been cancelled like the tour in 1972 was. The government officials could not anticipate, however, that the country was about to fall into “near-civil war.” In response to HART, pro-rugby groups like Stop Politics in Rugby (SPIR) organized in an effort to help the Springbok’s tour succeed. Both sides tended to be easily identified by armbands that made their affiliation clear. In particular, HART activists wore their armbands for the entire length of the tour, subjecting themselves to constant ridicule and the threat of violence, despite their commitment to nonviolent protest only.

The Springboks played their first game on July 22 in Gisborne. An anti-Springbok rally took place that day, near the rugby pitch. When the campaigners arrived at the arena, they were confronted by pro-rugby demonstrators. Because Gisborne, like most cities in New Zealand, was close-knit, demonstrators on both sides knew each other, and were not afraid to call each other out for supporting the wrong side, whichever they believed that was. The pro-rugby demonstrators did not restrict themselves to words, even throwing stones at the other side. The anti-Springbok protesters could not stop the match that day. Though they were able to break through the perimeter fence, and engage the pro-tour demonstrators face to face, they were prevented from occupying the field. Though both sides reported that they were uneasy with the clashes between fellow New Zealanders, neither side was easily swayed.

Three days later, the Springboks were scheduled to play in Hamilton. Anti-Springbok planners had circulated a strategy that would hopefully allow them to tear down the fence, invade the field, and disrupt the match. Protesters had also secured more than 200 official tickets to the match, to make sure that their presence was felt, even in the event that they could not storm the pitch. Despite the presence of more than 500 police officers and a sizable pro-rugby contingent, the anti-Springbok march would prove unstoppable. 5000 anti-Springbok protesters descended upon the Hamilton pitch, and more than 300 made it onto the field, forcing a match cancellation. Protesters chanted that the whole world was watching. Many of the demonstrators were arrested, and those on the pitch endured a constant bombardment of bottles and other objects from rugby fans in the stands. This entire situation was captured on live TV and shown around the world.

With tensions in New Zealand reaching astronomical proportions, the Springboks were next scheduled to play four days later, on July 29. The anti-Springbok protesters were largely absent from the match, but had instead planned a march on the South African consulate in Wellington, New Zealand. Despite police declaring that a march was not permitted, the protesters marched right up to the police line on Molesworth Street. The police began to stop the marchers with their batons, violently forcing them away from the consulate building. The marchers, stunned and bloodied, turned towards the police station, chanting “Shame, shame, shame.” When they arrived, the accosted marchers pressed assault charges on the police that had attacked them. Though the charges were dismissed, the policing of the tour protests had taken a turn for the worse. From this point on, protesters were careful to carry shields and wear crash helmets in order to protect themselves from attacks.

Protests would continue for the entire length of the Springbok’s stay in New Zealand. Only one more match was cancelled, in Timaru. However, there were a few more notable encounters. In Christchurch, on August 15, protesters failed to occupy the pitch in time for the game to be cancelled. The police cordon around the arena held, and several observers believe that the police saved the lives of many protesters. The attacks of rugby supporters were growing more and more violent, The Christchurch incident was characterized by flying blocks of cement and full beer bottles. Had the anti-Bok protesters succeeded in reaching the field, the attacks would certainly have been even more dangerous.

The final match of the tour was in Auckland on September 12. Not only was the match important as a final chance for protesters to demonstrate their opposition to the Springboks, it was the deciding third meeting between the Springboks and the All Blacks. Doug Rollerson of the 1981 All Blacks recalled that it seemed very important for the All Blacks to win the match, to show that a mixed team was superior to the segregated Springbok side. When the All Blacks won, the sense of victory in New Zealand was similar to the US victory over the Soviet Union in 1980 – the triumph of righteousness over the evil empire. However, for most observers around the world, the off-field events were far more important. Though the protesters were generally non-violent, there were many others that joined in the marches – HART characterized them as opportunists that simply wanted to fight with police. Though eruptions of violence had taken place throughout the campaign, they were largely viewed by the protesters as third-party actions, and HART consistently distanced themselves from violent attacks. More memorably, Max Jones and Grant Cole commandeered a prop plane, and proceeded to drop flares and flour bombs on the pitch during play in an attempt to stop the game. Though the game continued, the actions of the protesters were again the primary news story in New Zealand and throughout the world.

Though the anti-Springbok protests were largely unsuccessful in that the vast majority of the planned contests took place, they were able to raise an incredible amount of awareness for the anti-Apartheid movement. Nelson Mandela recalled that when the game in Hamilton was cancelled, it was “as if the sun had come out.” HART would continue protesting until the fall of the Apartheid regime.

Influenced and influenced by anti-Springbok protests in other countries like Australia, Britain (see "Australians campaign against South African rugby tour in protest of apartheid, 1971" and "British Citizens Protest South African Sports Tours (Stop the Seventy Tour), 1969-1970") (1,2).

This campaign was also influenced by the New Zealand Waterfront Strike (1951) (1).

Additional Notes

Name of researcher, and date dd/mm/yyyy.

True Crime New Zealand (NZ)

A nz crime podcast, history iv: 1981 springbok rugby tour (part i).

Apartheid even extended to sport. Leagues were established in all sports, separated by race. For instance, football (soccer) was divided into the white South African Football Association , the African Indian Football Association , the South African African Football Association , the South African Bantu Football Association , and the South African Coloured Football Association .

This led to many countries boycotting international play of various sports with South Africa. The International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) banned South Africa from international games.

However, the world governing body for the sport of rugby union, the International Rugby Board (now called World Rugby ) did not suspend South Africa from international games, and South Africa remained a member throughout the apartheid era.

Visit www.truecrimenz.com for more information on this case including sources and credits.

Hosted by Jessica Rust

Written and edited by Sirius Rust

Music sourced from:

Day of Chaos by Kevin MacLeod Link: https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song/3620-day-of-chaos License: https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Organic Meditations Two by Kevin MacLeod Link: https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song/4179-organic-meditations-two License: https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Leaving Home by Kevin MacLeod Link: https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song/4708-leaving-home License: https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

Clean Soul by Kevin MacLeod Link: https://incompetech.filmmusic.io/song/3514-clean-soul License: https://filmmusic.io/standard-license

HISTORY IV: 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour (PART I)

Chapter i: apartness, introduction to apartheid.

In 1909, the British colonies of the Cape of Good Hope , Natal , Orange River Colony and Transvaal were granted self-government under the South Africa Act of 1909 . The Act united the colonies under the banner of the Union of South Africa .

The Act also enfranchised white Africans , removing the right of black Africans to sit in parliament; giving complete political control over all other racial groups. Even though, blacks made up approx. 80% of the population of South Africa .

This power extended as the government introduced other legislation, including the Representation of Natives Act of 1913 which removed blacks from the voters’ roll, the Urban Areas Act of 1923 which introduced residential segregation, and the Asiatic Land Tenure Bill of 1946 which banned land sales to Indians and people of Indian descent.

In 1948, a new Government came to power, the Reunited National Party (changed later to simply the National Party ) , led by Prime Minister Daniel Francosis Malan . It was at this time that Apartheid was introduced. Apartheid, which is an Afrikaans word that translates in English to ‘apartness’ , was an ideology introduced which called for the separate development of the different racial groups.

In the years after this ideology was brought in, many Apartheid laws were introduced. Including the Population Registration Act of 1950 which mandated that the population of South Africa register under a specific racial group (either white, black or coloured) , the Group Areas Act of 1950 which mandated physical separation of different races, the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 which banned marriages of two different races, the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act of 1953 which reserved separate beaches, buses, trains, hospitals, schools and universities for different racial groups, and the Immorality Amendment Act of 1950 which forbid unmarried sexual intercourse between whites and any other race.

Apartheid had many critics. None is more famous than the South African anti-apartheid revolutionary and political leader Nelson Mandela . In 1943 , Nelson joined the anti-colonial political group, the African National Congress (ANC) . After apartheid began, Nelson Mandela and the ANC shifted their focus to overthrowing the white-only government.

In 1956, Nelson was arrested for seditious activity and successfully tried for treason by the South African government. Nelson Mandela spent the next 27 years in prison.

APARTHEID IN SPORT

Chapter ii: a fine disregard for the rules of football.

The origins of the sport of Rugby are somewhat unknown. The most widely told theory was that it was created in 1823 at Rugby School , in the market town of Rugby in Warwickshire, England . The legend goes that a pupil of the school William Webb Ellis , whilst playing the traditional game of football (soccer) caught the ball in his hands and ran with it. Thus creating the game as we know it today, changing the game from a kicking game to a handling game .

The legend reportedly comes from a former student of Rugby School, Matthew Bloxam , who wrote a letter to the Rugby School magazine, The Meteor , in 1876 (the year William Webb Ellis died) who told the story of the young boy catching the football and running forward. Matthew wasn’t there that day, claiming he was told the ‘running forward story’ by an unknown source.

Nevertheless, Matthew repeated this story four years later, once again to The Meteor, on the 22nd of December 1880 , “A boy of the name Ellis – William Webb Ellis – a town boy and a foundationer, … whilst playing Bigside at football in that half-year [ 1823 ], caught the ball in his arms. This being so, according to the then rules, he ought to have retired back as far as he pleased, without parting with the ball, for the combatants on the opposite side could only advance to the spot where he had caught the ball, and were unable to rush forward till he had either punted it or had placed it for someone else to kick, for it was by means of these placed kicks that most of the goals were in those days kicked, but the moment the ball touched the ground the opposite side might rush on. Ellis, for the first time, disregarded this rule, and on catching the ball, instead of retiring backwards, rushed forwards with the ball in his hands towards the opposite goal, with what result as to the game I know not, neither do I know how this infringement of a well-known rule was followed up, or when it became, as it is now, a standing rule.”

This story is largely disregarded as an urban legend as other students who were there that day at Rugby School deny this ever happened.

Nevertheless, Rugby School believes the story to be true, as it erected a plaque to commemorate the event that reads: “This stone commemorates the exploit of William Webb Ellis who with a fine disregard for the rules of football as played in his time first took the ball in his arms and ran with it, thus originating the distinctive feature of the rugby game A.D. 1823”.

The Rugby World Cup is also known as the Webb Ellis trophy to honour the event.

RUGBY IN NZ

Rugby was first introduced in New Zealand in 1870 by Charles John Monro , the son of then-Speaker of the House of Representatives , David Monro . Charles had encountered the game while he was studying at Christ’s College Finchley in London, England .

The first rugby match was played on the 14th of May 1870 at Nelson College (Nelson Rugby Club vs. Nelson College) . Later that year, Charles Monro organised a match in Wellington (Nelson vs. Wellington) . From here, rugby spread quickly throughout the colony, with games being played in Whanganui, Auckland and Hamilton.

The first international game took place in 1882 when the Australian team, the New South Wales Waratahs, visited both of NZ’s islands; playing games against the many provincial teams. In 1884 , a New Zealand team (wearing a blue jersey with a golden fern) visited New South Wales for a tour.

In 1892 the New Zealand Rugby Football Union was created, a national governing body for rugby in Aotearoa . The first official tour took place in 1893 when the NZ team visited Australia for a ten-game tour.

In 1888, an NZ rugby team toured further than Australia for the first time, venturing to Britain . The team was dubbed The Natives due to being predominantly made up of Maori players (although five Pakeha players also toured with the team) . It was during this tour that a haka (a Maori ceremonial war dance) was performed before each game. The haka, Ka Mate , was composed by Te Rauparaha , a Maori chief in 1820 . Ka Mate is a celebration of life after Te Rauparaha was hidden by another friendly Maori chief Te Wharerangi from his pursuing enemies:

Ka mate, ka mate! ka ora! ka ora! Ka mate! ka mate! ka ora! ka ora! Tēnei te tangata pūhuruhuru Nāna nei i tiki mai whakawhiti te rā Ā, upane! ka upane! Ā, upane, ka upane, whiti te rā!

Which translates in English to:

‘Tis death! ’tis death! ‘Tis life! ’tis life! ‘Tis death! ’tis death! ‘Tis life! ’tis life! This is the hairy man Who summons the sun and makes it shine A step upward, another step upward! A step upward, another… the Sun shines!

In 1905, a New Zealand team toured the British Isles . The legend goes that a London Newspaper wrote about the players, saying that the team played like they were “all backs” . However, in subsequent references to the team, in an apparent typo, ‘all backs’ became ‘all blacks’ . This is again a myth that originated from one of the NZ players, Billy Wallace . It was more likely they were already called the All Blacks before they left NZ due to their all-black uniform.

The 1905 NZ rugby team is now known as The Originals (or the Original All Blacks ) and they won 34 out of 35 of their games throughout the British Isles .

In 1924, the All Blacks toured the British Isles once more. This time the team was dubbed “The Invincibles” as they won every game of the tour.

During the 1900s, Rugby became New Zealand’s national sport, something that is built into the culture of Aotearoa, similar to football in England or hockey in Canada . The official New Zealand tourism website 100% Pure New Zealand (or, newzealand.com ) describes NZ’s infatuation with the game as, “Rugby in New Zealand is more than just a game, it forms the sporting backbone of the nation. From grassroots to international super-teams, rugby is supported by passionate kiwi fans. Rugby is the national obsession of New Zealand and a huge determining influence on New Zealand life and culture. Rising from cities, small towns and country paddocks, no part of New Zealand’s landscape is quite complete without a set of Rugby goal posts. There are signs of the sport at every corner, whether it’s a young boy perfecting his kick at the park or a proud supporter wearing his team’s shirt to the mall, you can’t help but be captivated by the game.”

HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ALL BLACKS

In 1949 (a year after Apartheid was implemented) , an all-white All Blacks toured South Africa, losing all four games. The team was forced to play without their Maori players due to Apartheid (the All Blacks refused to do a haka in South Africa in protest of this) .

The Maori players stayed in NZ and played games against Australia for the Bledisloe Cup . Losing both games and awarding the Bledisloe Cup to Australia.

In 1960, the All Blacks toured South Africa once more. Once again, Maori and Samoan players were banned by the South African government. This led to the New Zealand Rugby Union forbidding any more tours of South Africa.

In 1969, the Halt All Racist Tours (HART) protest group was established in New Zealand. Their goal was to stop all tours of South Africa until apartheid was dismantled.

The ban on NZ’s tours of South Africa lasted until 1970 when the All Blacks toured South Africa once more. This was only on the condition that New Zealand players of all racial backgrounds were allowed to play. The South African government conceded and allowed Maori and Samoan players under the status of “Honorary Whites” for the duration of the tour.

In 1972, in the run-up to the general election, Labour opposition leader, Norman Kirk promised the public that a Labour government would not interfere with the upcoming Springbok tour .

Labour was brought into power in late 1972 , however by 1973 (the year of the proposed tour) , Norman Kirk claimed that the potential for civil unrest was too high and postponed the upcoming Springbok tour on the 10th of April 1973 . Labour’s ‘flip-flop’ on this issue raised a lot of criticism from NZ folk that believed sport and politics shouldn’t mix, but Norman Kirk defended the government’s decision by saying that he would be failing in his duty as Prime Minister if he didn’t “accept the criticism and do what [he] believed to be right” .

The decision was also made on the advice of the Police that if the Springbok tour did proceed, it would “engender the greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known” . It is also believed that the decision was made due to Christchurch hosting the 1974 Commonwealth Games , which black African nations would boycott if the tour went ahead.

Labour lost the 1975 election by, what was dubbed, ‘a landslide’ , bringing a National government back into power, led by Robert Muldoon . Muldoon gave his blessing for a new Springbok tour in New Zealand, “even if there were threats of violence and civil strife”. Many believe it was this issue that led to National’s overwhelming victory.

In 1976, the All Blacks toured South Africa once more under the same conditions as the last tour. Five Maori players were given honorary white status; along with one ethnic Samoan. Twenty-five African nations protested against the tour by boycotting the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, Canada . They saw the All Blacks tour as the NZ government giving their tacit support to the apartheid regime.

The New Zealand All Blacks had lost all three of the last tours of South Africa. However, political unrest in NZ was growing around the continued tours of South Africa. This set the stage for five years later when the South African rugby team (the Springbok ) were set to tour New Zealand.

Protests organised by HART and other groups were gaining momentum. Calls to ban the tour reached Prime Minister Robert Muldoon. Protesters argued that Robert Muldoon signed the 1 977 Gleneagles Agreement , signed by all Commonwealth Presidents and Prime Ministers as a show of support against apartheid, and allowing South Africa to enter NZ to play rugby would contradict this agreement. The Gleneagles Agreement even specifically referenced opposition to participating in sport with South Africa, “the urgent duty of each of their Governments vigorously to combat the evil of apartheid by withholding any form of support for, and by taking every practical step to discourage contact or competition by their nationals with sporting organisations, teams or sportsmen from South Africa or from any other country where sports are organised on the basis of race, colour or ethnic origin”.

However, NZ Prime Minister Robert Muldoon argued against this, stating, “politics should stay out of sport” . And, with that, the Springbok rugby tour was set for July 1981 .

CHAPTER III: WE DON’T WANT YOUR RACIST TOUR

Lead up to the tour.

In the lead up to the 1981 Springbok tour protests throughout the country were planned to show their outrage at the rugby tour going ahead. Although the protesters were committed to non-violent civil disobedience, two special police riot squads were created; Red and Blue Squads.

Second in charge of the Red Squad was then 32-year-old policeman Ross Meurant. He told the New Zealand Herald on the 9th of July 2011 for the article ‘The rugby tour that split us into two nations’ that the police were put in a tough situation, and used as a political chess piece, “Personally, I believe [Prime Minister Sir Rob] Muldoon unashamedly used the police in a cynical political initiative of dividing the nation over rugby to gain a marginal win at the polls on the support of conservative, rugby-loving provincial electorates”.

However, he added that the police had no choice but to defend civil order, stuck between a rock and a hard place, “ To this day I still defend that police action. We had no choice. We were the meat in the sandwich – fail and the institutions of the State would have been emasculated by a competing brute force. But the police were cynically used for a political objective.”

The New Zealand Security Intelligence Service (NZSIS) was also concerned about these upcoming protests; evidenced by a declassified document dated the 11th of July 1981 . The document outlines that the NZSIS were concerned with ‘subversive’ groups, especially the Workers Communist League (WCL) ; the document reads in part, “The Workers Communist League in Wellington is a radical group and involved in COST (Citizens Opposed to the Springbok Tour). COST can be viewed as a WCL ‘front’ hence coming within the Service’s CS area of interest but there are no indications of violent activity emanating from this quarter. The Service has some peripheral coverage of this group.”

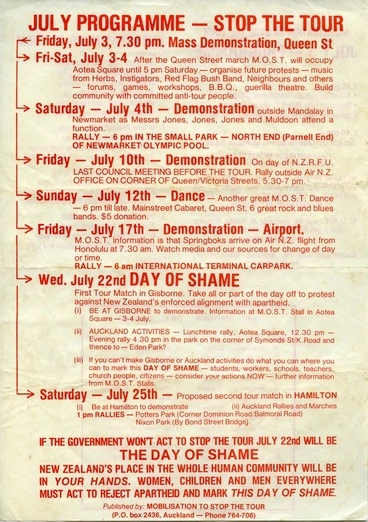

A schedule of protest activities was published by Mobilisation to Stop the Tour (MOST). MOST dubbed the day the tour was to kick off as ‘The Day of Shame’ , “If the government won’t act to stop the tour July 22nd will be the day of shame. New Zealand’s place in the whole human community will be in your hands. Women, children and men everywhere must act to reject apartheid and mark this day of shame”.

The protesters even had an Anti-Apartheid Anthem to sing at the protests that were printed on the reverse of the schedule pamphlet produced by MOST:

In New Zealand, we are taught To play fair and decent sport That’s why we’re marching here tonight You can’t play games with APARTHEID

We don’t want your racist sport Apartheid kills and it must be fought The multinationals don’t count the dead They count the profits they grab instead

Don’t want racists in our land Apartheid’s killers with bloody hands Working people the whole worldwide Against oppression, we’ll stand and fight

We don’t want your racist tour It is freedom we’re fighting for We don’t want your racist tour It’s liberation we’re fighting for

CONNECTING TISSUE

The Springbok rugby team arrived from South Africa on the 19th of July 1981. The first game of the tour was set for the 22nd of July 1981 in Gisborne . New Zealand was unprepared for what was to unfold in the succeeding 56 days, the division between regular New Zealanders, those for the tour and those against, sometimes even within one’s own family.

This is evidenced by an anonymous contributor to the book The New Zealand Experience: 100 Vignettes by Kathy Broadley and Brian Shaw . In the book, the contributor describes living within a family divided by the Springbok tour, “Although things had been far from perfect between my parents, the Springbok tour caused such tension and stress that we could not live together in the same house and function as a family unit. An example of the increase was when we, as a family, watched the evening news. Often one side would raise their voices in abuse and offensive name-calling toward public figures. Later the abuse was turned in an indirect way on individual family members. This was done by blaming the chaos and disruption to rugby games [on] individual family members, their friends and associations. As the tour went on and the turmoil increased, the negative feelings intensified to such a degree that feelings of dislike, anger and incomprehension dominated our home.”

Over the next 56 days, 150,000 people in over 200 demonstrations in 28 centres around the country would show their displeasure at the tour going ahead. The anti-apartheid protesters were met with counter-protests, usually by folk just showing up to see the games; left vs. right, protester vs. anti-protester, New Zealander vs. New Zealander.

New Zealand was about to experience something she had never experienced before, near civil war.

[END OF PART I]

CHAPTER I Wikipedia, Nelson Mandela, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nelson_Mandela Wikipedia, Herenigde Nasionale Party, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herenigde_Nasionale_Party Wikipedia, Apartheid, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apartheid Wikipedia, South Africa Act 1909, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Africa_Act_1909 Wikipedia, 1948 South African general election, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1948_South_African_general_election South African History Online, A history of Apartheid in South Africa, https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/history-apartheid-south-africa