The Impact of ‘TRIPS-Plus’ Rules on the Use of TRIPS Flexibilities: Dealing with the Implementation Challenges

- Conference paper

- Open Access

- First Online: 28 October 2021

- Cite this conference paper

You have full access to this open access conference paper

- Mohammed El Said 3

14k Accesses

3 Citations

Improving the health and well-being of society is a priority to many governments. One essential element within this debate focuses on the accessibility and affordability of medicines for patients. Although interest in this area has persisted for decades, the recent shift in this field is manifested by this now being treated as a global concern, rather than as a regional or a national one. Patients in both developed and developing countries alike are facing the same challenges and are under an increased pressure to access and afford treatment. The recently published UN High Level Panel for Access to Medicines Report explicitly stated its view of ‘access to medicines, vaccines, diagnostics and related health technologies as a serious, multidimensional global problem, with challenges that affect all people and all countries.…the High-Level Panel recognizes that the costs of health technologies are rising globally and are being felt by individuals and by public and private insurance schemes in both wealthy and resource-constrained countries alike’ (UN Secretary General High Level Panel, ‘The United Nations Secretary-General High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines Report: Promoting Innovation and Access to Health Technologies’, (September 2016), 12. https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23068en/s23068en.pdf .). This thinking represents a fundamental departure from the previous approach which classified the problem related to access to medicines as one mainly attributed to developing and least developed nations. It is within this debate that the role of intellectual property protection in general and by way of the rise of TRIPS-Plus agreements and their impact on accessibility and affordability of medicines takes centre stage.

The author would like to thank Professor Graham Dutfield for his valuable feedback and insights on this chapter. The usual disclaimer applies.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Between Regional Recommendations and National Implementation: An Analysis of the East African Community Partner States’ Legislative Responses to TRIPS Obligations

Olugbenga A. Olatunji

Equitable Access to Medicines, Vaccines, and Medical Devices

Policy approaches to improve availability and affordability of medicines in mexico – an example of a middle income country.

Daniela Moye-Holz, Jitse P van Dijk, … Hans V. Hogerzeil

1 Introduction

There are many factors which impacts the access to medicines debate. Government policy, industrial development, demography, manufacturing capabilities, market conditions and procurement and tax regimes are some factors. However, for some time, the role of intellectual property monopolies especially patents granted to innovator drug companies to protect their research and development (R&D) investments and provide market exclusivity by restricting competition became an integral part of this debate. Footnote 1 This chapter will look at various factors affecting the accessibility and affordability debate and will focus on the role of intellectual property protection in that process. It will provide useful examples of the positive impact arising from the use of the TRIPS flexibilities and on the other hand will explain the dangers affiliated with adopting TRIPS-Plus regimes in this regard. It will also provide examples of practises and strategies which would limit the impact of TRIPS-Plus commitments under national laws.

2 Expensive Medicines: National Implications and Global Challenges

The price of medicines has been on a steady increase for some years. In the US, prices for branded prescription drugs doubled in five years between the period of 2011–2016. Footnote 2 Further, it was projected that the prices of medicines in the US will increase on average 5.8% in 2020. Footnote 3 More than 13% of Americans—about 34 million people—say a friend or family member recently passed away in the last five years after being unable to afford treatment for a condition while 58 million adults report inability to pay for needed drugs in the past year, according to a new poll from Gallup and West Health. Footnote 4 A recent study in the UK found that total National Health Service (NHS) spending on medicines in England has grown from £13 billion in 2010/11 to £17.4 billion in 2016/17—an average growth of around 5% a year. The same study concludes, ‘These figures are uncertain due to gaps in data, but the rate of increase is substantially faster than for the total NHS budget over the same period’. Footnote 5 With the prevalance of the COVID 19 pandamic, pressure on national health providers have reached unprecedented levels.

The year 2019 was phenomenal in terms of setting new high records in medicines prices. In March 2019, the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) approved the most expensive medicine in history up to date called Zolgensma (priced at $2.125 million), a medicine used for a rare disorder that destroys a baby’s muscle control and kills nearly all of those with the most common type of the disease within a couple of years. Other more commonly used medicines’ prices have also been notably high. For example, a 2018 WHO report on cancer medicines concluded that ‘in the absence of insurance coverage, cancer treatment is unaffordable for many patients. A course of standard treatment for early stage HER2 positive breast cancer (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, trastuzumab) would cost about 10 years of average annual wages in India and South Africa and 1.7 years in the United States of America. The costs associated with other medical care and interventions (such as surgical interventions and radiotherapy) and supportive care (such as anti-emetics and haematopoietic growth factors) would make overall care even more unaffordable. Even with insurance coverage, patients living with cancer in many countries have reported financial stress, to the extent that they may lower the treatment dose, partially fill prescriptions or even forego treatment altogether’. Footnote 6 In France, in December 2015, the Ligue contre le cancer—which spends around €38 million ($43 million) a year on cancer research, making it the largest French non-governmental funder of cancer R&D—condemned cancer drug prices as ‘exorbitant, unfair and unbearable’ and warned that if unabated, price inflation for new drugs posed a direct threat to the French medical system Footnote 7 while others have expressed that “economic considerations significantly influence and, in some instances, take precedence over the scientific evidence” with relation to French Guidelines on antiretroviral therapy treatment. Footnote 8

Newly developed hepatitis C drugs’ prices have also raised eyebrows. The efficient drug Sovaldi was launched at a list price of $84,000 for a standard twelve-week treatment course, or about $1000 a pill. At the most recent average net price of $45,000 per patient for all sofosbuvir-based products in the US, it would cost $135 billion dollars to treat the estimated three million people with chronic hepatitis C in the US—over one third of total annual spending on all prescription drugs in the US. Footnote 9 In the UK, the list price for a 12-week course of sofosbuvir was nearly £35,000 (excluding VAT) and double that for a 24-week course. Footnote 10 Notwithstanding the high price, in early 2015 sofosbuvir was recommended for funding based on its cost effectiveness. However, because of the budget impact of the treatment, in the following months the NHS England delayed consistent provision of sofosbuvir, instead phasing introduction through the use of quotas and prioritising patients with the most severe need. Footnote 11 From 2012 to 2019, the average price of AbbVie’s rheumatoid-arthritis drug Humira climbed from $19,000 a year to $60,000 a year. Footnote 12

The effects of this are felt in both developed and developing countries. Greater number of patients are now unable to afford medicines while governmental health budgets are struggling to cater for the needs of its citizens, a situation made worse during the COVID 19 pandamic. Henceforth, patients in the developing countries are lacking essential medicines and lifesaving treatments, diabetics have died in the US due to high price of insulin while the Dutch government has had to suspend its acquisition of the immune-oncology drug Keytruda (despite the fact that it helped in its development) because it was too expensive. Footnote 13 The NHS in the UK—a wealthy country which, unlike the United States, has a publicly funded and all-inclusive health service with considerable bargaining power—is having to ration the supply of cancer drugs due to financial restrictions on treatment Footnote 14 while waiting times for those actually offered the treatment are far too lengthy. Footnote 15

3 Unequal Investment and More Monopoly

The problem which high prices of medicines poses should not be viewed in isolation of other contributing factors engulfing this debate. One issue which ranks high within this context is the challenge of inadequate funding for diseases primarily affecting the financially underprivileged or for which the opportunities to make large and long-term profits are considered by the industry to be limited.

Growing criticism has been made regarding the deficiency of the global regime in finding solutions to long standing diseases (or as some refer to as neglected diseases) or the unequal distrbution of COVID 19 vaccines as an example. One visible area of concern is that related to the development of new antibiotics, an issue the WHO have classified as a global challenge in recent years. According to WHO, “No major new class of antibiotics has been discovered since 1987 and too few antibacterial agents are in development to meet the challenge of multidrug resistance.” Footnote 16 One of the main issues related to lack of investment and R&D in this field is attributed to the industry’s fear that resistance to these drugs would develop eventually hence eliminate the usefulness of the drug rapidly which may explain why most major pharmaceutical companies have stopped research in this area, a situation that has been described as a “serious market failure” and “a particular cause for concern”. Footnote 17

In a recently published two reports, the WHO warned about the adverse effects of the declining private investment and lack of innovation in the development of new antibiotics. The WHO further highlighted how this is also undermining efforts to combat drug-resistant infections and diseases. The WHO reports found that the 60 products currently in development (50 antibiotics and 10 biologics) bring little benefit over existing treatments and very few target the most critical resistant bacteria (Gram-negative bacteria). Footnote 18 The Chairman of the UK Review on Antimicrobial Resistance warned recently that, if left unaddressed, drug-resistant infections could be responsible for the deaths of some ten million people a year by 2050, and $100 trillion in economic damage. Footnote 19

Other neglected diseases also share similar challenges and evident lack of investment and innovation. For example, a 2002 analysis of new chemical entities developed between 1975 and 1999 found that only 1.1% were actually treatments devoted to tuberculosis (TB) and tropical diseases, despite them causing 11.4% of the global disease burden. Footnote 20 Although the years between 2000 and 2011 witnessed some improvement whereby of the 850 new therapeutic products registered, 4.4% were for neglected diseases. Footnote 21 However, according to the same study, only 4 of the 336 new chemical entities brought to the market during the same period were for neglected diseases (including malaria)—just 1.2% of the total.

TB which is the biggest infectious disease killer in the world today is another case in point, whereby the death toll alone in 2014 was 1.5 million lives. Until very recently, no new drug was introduced for nearly 50 years . Footnote 22 Furthermore, the last treatment—largely inadequate due to its side effects—developed for Chagas disease (leading cause of infectious heart disease in Latin America) was over 40 years ago.

Ebola also placed the global treatment regime under security. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) who often operates within the disease-stricken countries further states that the ‘fact that MSF frontline health workers lacked a treatment or a vaccine for Ebola virus as the outbreak engulfed Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia in 2014 is a poignant illustration of this problem. But the problem of inadequate or non-existent treatments and vaccines was a challenge for MSF long before 2014’. Footnote 23 Notably, it was only in late 2019, it was announced that a new vaccine was approved in the US and EU for Ebola. Footnote 24

4 The Double Taxation of Society

One of the strongest criticisms against pharmaceutical companies is the way they engage in business activities and R&D operations. It is vital to acknowledge that innovator pharmaceutical companies need incentives to protect their investments. Yet to what extent that should be sought at the expense of public health policy concerns is questionable. The high prices of medicines does not only have a negative effect regarding accessibility, but have also attracted criticism due to the fact that a vast number of medicine discoveries and some of the subsequent drug development, or indeed much of it in some cases, was funded by tax payers. The situation is made worse by anticompetitive behaviour of some of these companies.

It is no secret that the governmental levels of financial and technical support for biomedical innovations are considerable. The public sector makes substantial contributions to research and development upfront, through grants, subsidies and tax credits. In fact, some studies suggest that 30% of the estimated $240 billion yearly total global investment across all health R&D comes from the public sector. Footnote 25

Several cases illustrate this, including Truvada. The drug was initially developed and patented by the US government after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received $50 million in federal grants in addition to $7 million from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in 2015. However, the government did not receive any income and no improvement in terms of accessibility rates was observed (it is believed that less than 10 percent of the 1.1 million people who should be on treatment are receiving it) despite the fact that Gilead Sciences the maker of the drug earned $3 billion in sales in 2018 prompting the US government to initiate legal action against Gilead. Footnote 26

Moreover, a study found that during the past four decades, 153 new FDA-approved drugs, vaccines, or new indications for existing drugs were discovered through research carried out in public sector research institutions (PSRIs). It was reported that these drugs included 93 small-molecule drugs, 36 biologic agents, 15 vaccines, 8 in vivo diagnostic materials, and 1 over-the-counter drug. More than half of these drugs have been used in the treatment or prevention of cancer or infectious diseases. Footnote 27

Similar trends are observed elsewhere outside the US. In 2017, campaigners in the UK claimed that the NHS spent more than £1 billion on drugs developed from publicly funded research in 2016. A report published by campaign groups Global Justice Now and Stop Aids claimed that UK tax payers and patients worldwide are being denied the medicines they need, despite the public sector playing a pivotal role in the discovery of new medicines. It concluded that ‘In many cases, the UK taxpayer effectively pays twice for medicines: first through investing in R&D, and then by paying high prices for the resulting medicine once ownership has been transferred to a private company.’ Footnote 28 The report cites several examples of drugs which received public funding but now are out of the reach of majority of patients. For example, the report explains how Alemtuzumab was originally developed at Cambridge University and first approved for the treatment of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (B-CLL). Cambridge scientists then led further investigations of its usefulness, at a smaller dosage, in treating multiple sclerosis (MS). Sanofi Genzyme, who had acquired the rights to the drug, removed it from the market as a B-CLL medicine and re-launched it as a medicine for MS. The Report verifies that ‘At the time of withdrawal there was speculation that the exercise was motivated by commercial reasons. When it was used off-label (i.e. used for a non-licenced purpose) for MS prior to being withdrawn from the market, the price in the UK was around £2,500 per MS treatment course in 2012’. In 2017, it costs was £56,000 per treatment course—a 22-fold increase. Footnote 29

On the other hand, several anticompetitive practises have had a far-reaching impact on prices. Even when there are opportunities to reduce prices, we find that this is not taken advantage of (and even intentionally delayed). A recent study found that of the more than 1600 generic drugs approved by the FDA since January 2017, more than 700—or 43 per cent—are not for sale in the US. Footnote 30

Delaying tactics have also incurred huge costs on society. One study estimates that the American health system is poised to incur $55 billion during the next 15 years on three drugs (related cancer and hepatitis C treatment) alone due to patents blocking and delaying the entry of generic competition on these drugs only. Product lifecycle management, whereby branded companies obtain unmerited patents to delay competition, Footnote 31 is the primary strategy identified and evaluated by this study. The study also highlights that another related strategy is “pay-for-delay” whereby branded companies pay generics to stay off the market for some time. Footnote 32

5 More Pharmaceutical Patents, Weaker Innovation

An equally troubling development which has contributed to the increase in medicines prices and extended monopoly patent terms in recent years is the increase in the number of drug patents granted, particularly those ‘inventions’ which are of a low and inferior quality, or as may be referred to as frivolous/trivial patents. This process is leading to what is referred to as the ‘evergreening’ of drugs. Footnote 33

This development may be explained by looking at some national statistics in this regard. For example, it was found that between the years 2006 and 2016, the number of drug patents granted in the US doubled. The granted patents were mainly dedicated to accumulating patents not for new medicines but rather for small changes to existing ones, which allows them to build and extend monopolies, block competition and drive prices up. Footnote 34 Moreover, on the 12 best-selling drugs in the US, drug makers have filed an average of 125 patent applications and have been granted an average of 71 patents for each. Footnote 35 Another study found that 74 applications have been filed on Lantus (it is a man-made form of a hormone (insulin) that is produced in the body which works by lowering levels of glucose (sugar) in the blood) only in the US, which have the potential to delay competition for 37 years. Footnote 36 This kind of “over patenting” blocks competition and enables pharmaceutical companies more freedom to regulate the pricing market of medicines. Footnote 37

Elsewhere the findings are similar. A study in Australia found an average of 49 secondary patents granted for each of the 15 highest-cost drugs over a 20-year period. One-quarter of these secondary patents were believed to be evergreening patents. Footnote 38 The Office of Patented Medicines and Liaison at the Therapeutic Products Directorate of Health Canada estimates that 44% of the 419 medicines on the Patent Register are covered by more than one patent. Footnote 39

Moreover, an EU investigation concluded in 2008 that out of the 219 molecules in the sample under the investigation, originator and generic companies identified at least 1300 patent-related out of court contacts and disputes concerning the launch of generic products in the period 2000 to 2007. The vast majority of disputes were initiated by the originator companies, which most often invoked their primary patents, e.g. by sending warning letters. In this respect the inquiry finds that individual medicines are protected by up to nearly 100 product-specific patent families, which can lead to up to 1300 patents and/or pending patent applications across the Member States. Despite the lower number of underlying patent families based on European Patent Office (EPO) applications, looking from a commercial perspective, ‘a challenger may, in the absence of a European Community patent, need to analyse and possibly confront the sum of all existing patents and pending patent applications in those Member States in which the generic company wishes to enter’. Footnote 40

Elsewhere, another analysis found of the 1015 new drugs and indications approved in France between 2004 and 2013, only 6.3% offered a clear therapeutic advantage, almost none were considered breakthroughs, and the majority (69.3%) offered no clear therapeutic benefit or were prematurely approved even though their clinical evaluation showed them to be more harmful than beneficial. Footnote 41 A second analysis found that 85 to 90% of new products approved over the last four decades have provided only limited benefits. Footnote 42 A third study that looked not just at registered products, but specifically at new chemical entities and new biologics, found that the majority of those launched in the UK between 2001 and 2012 were only “slightly innovative” and only a quarter (26%) were believed to be “highly innovative”. Footnote 43

Rather than using the patent regime as an incentive to innovate and recoup investment for worthy inventions, ‘evergreening’ tactics and practises are in fact blocking accessibility and weakening innovation capabilities by undermining the true foundations of the patent regime and turning it into monopoly creator with no positive contribution to society’s needs. Footnote 44

6 Increased IP Standards: From TRIPS-Minus to TRIPS-Plus

The global regulation of intellectual property rights is a relatively modern concept. Prior to the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1996, countries had considerable policy space and full discretion in designing their national intellectual property legal regimes in accordance with their development stage and national priorities. Footnote 45 As such, a large number of countries did not award legal protection to patents related to drugs and pharmaceutical products. Footnote 46

This was no longer the case with the creation of the WTO. The Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (the TRIPS Agreement) Footnote 47 obligated member states to provide legal protection for inventions in all technological fields including pharmaceutical products. This was an important development whereby for the first time in history, countries lost the ability to regulate their national intellectual property regimes freely and in accordance with their national development plans.

Reaching consensus regarding the TRIPS agreement was not a simple act. The intellectual property negotiations during the Uruguay Round of Trade Negotiations were amongst the most contentious and complex. As such and in order to strike a balance between the rights of users and intellectual property holders on the one hand, and the society on the other, several ‘flexibilities’ were introduced within TRIPS in order to curtail the negative impact which may arise from excessive intellectual property protection and at the same time to enable countries to deal with their public health challenges and emergencies.

6.1 The Flexibilities Explained

The TRIPS ‘flexibilities’ may best be explained as options available to member states allowing them to comply with the TRIPS Agreement requirements and at the same time maximise the implementation space available to them in accordance with their priorities. Footnote 48 Following are some examples of the health-related flexibilities available under the agreement to member states:

Transitional periods. According to the WTO, least developed countries (LDCs) are given an extended transition period to protect intellectual property under the WTO’s TRIPS Agreement. This is in recognition of their special requirements and status, their economic, financial and administrative constraints, and the need for flexibility so that they can create a viable technological base. Several extensions of the transition period were provided by the TRIPS Council. The last 6th of November 2016 Council decision extends until January 2033 the period during which key provisions of the WTO’s intellectual property agreement, the TRIPS Agreement, do not apply to pharmaceutical products in LDCs. Footnote 49 This means LDCs can choose whether or not to protect pharmaceutical patents and clinical trial data before 2033. The decision also keeps open the option for further extensions beyond that date. Footnote 50

Compulsory licensing. A tool through which the state authorizes a third party to exploit patented inventions, generally against a specified royalty paid to the patent holder provided that several conditions set under the TRIPS Agreement (Article 31) are complied with. The objective behind this is to curtail anti-competitive behaviour and ensure the transfer of technology and dissemination of knowledge. Footnote 51

Government use exceptions. A tool which grants the state the right to use the patent without obtaining the consent of the patent holder for the purpose of public interest, including public health necessities. Although government use conditions are similar to compulsory licensing, government use exceptions provide an added advantage by fast-tracking the process, through granting the government the right to use the pharmaceutical patent without the need for prior negotiations with the owner.

Parallel importation. This tool gives the option to member states to obtain patented products when they are lawfully available in a foreign market at a lower price, thus enabling countries to shop for cheaper patented products. This requires as a prerequisite that a country adopt an exhaustion regime suitable to its needs and priorities. Footnote 52

Exceptions to patents rights. Article 30 of TRIPS provides that members “may provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent, provided that such exceptions do not unreasonably conflict with a normal exploitation of the patent and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the patent owner, taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties.” Footnote 53 However, the above provision does not define the scope of the permissible exceptions thus awarding member countries some considerable discretion to operate. Examples of these exceptions include the Bolar exception Footnote 54 and the research and experimental use exception.

Standards of patentability. Under TRIPS, patent protection must be granted for products and processes which are new , involve an inventive step and are industrially applicable . Footnote 55 However, each of these are not defined and can be interpreted and applied by member states in accordance with their national priorities and objectives. For example, TRIPS do not specify the patenting of new uses of known products, including pharmaceutical drugs, thus allowing member countries the possibility of rejecting these new uses for lack of novelty, inventive step or industrial applicability.

Other procedural flexibilities . Another identified policy tool that may be used to improve the quality of granted patents and limits “evergreening” is pre-grant and post-grant patent oppositions, in addition to patent revocation proceedings. These methods have been used at different times in a wide range of developed and developing countries. Such proceedings enable interested parties to bring claims before the patent office on the basis that a particular patent does not meet local requirements.

6.2 Putting the Flexibilities into Use

We now have a considerable body of literature and empirical research dedicated to the benefits of utilising the TRIPS Agreement’s flexibilities under national laws. Despite this, some would still argue that the use ‘of the TRIPS flexibilities has been sporadic and limited’ Footnote 56 and that more could still be achieved in this regard. Footnote 57

A much widely affiliated issue with the use of the flexibilities is the issue related to the impact of generic drugs entry into the market and the savings achieved as a result. In many cases, this is enabled by the flexibilities effect in curtailing ‘evergreening’ and in opposing low quality patents. As such, it is common to see medicine prices dropping substantially (ranging between 30–90 percent in some cases) when generic medicines enter a market following the expiry of a patent. Footnote 58

Compulsory licensing is the most used flexibility in this regard. Footnote 59 There is no scarcity of evidence with relation to the positive impact compulsory licensing has had upon improving access to medicines. Malaysia was one of the latest countries to issue a “government use” compulsory license to obtain much cheaper version of a generic version of the famously known hepatitis C medicine Sofosbuvir in September 2017. It is believed that compulsory license issuance have enabled treatment cost at RM1000 to RM1200 ($240–$285) for 12 weeks course, compared to RM300,000 (approx. $72,000) which was the cost of treatment with the patented version and prior to issuance of the license. Footnote 60 Moreover, it was reported that between 2013 and 2017, the Ecuadorian Institute of Intellectual Property (IEPI) issued ten compulsory licences for various medications including antiretroviral drugs. Footnote 61 According to health officials in Ecuador, the compulsory licenses granted between 2013 and 2014, generated the potential for savings of 23 per cent to 99 per cent. Footnote 62 Similar findings may also be found in the case of other compulsory licenses issued by Thailand, India, Indonesia, Brazil and Columbia. Footnote 63

One of the other important flexibilities available to countries is related to the issue of patentability standards. As highlighted, member countries have a wide discretion and freedom to apply and define the patentability criteria of an invention under their national regime. As such, India has applied a strict patentability criteria aimed towards limiting the number of frivolous or secondary pharmaceutical patents granted. Footnote 64 Although we cannot measures the direct price impact this will have on medicines nevertheless it is believed that the utilisation of this flexibility have a substantial impact in preventing patent abuses and the granting of low quality patents (anti-evergreening strategy). Footnote 65 Other countries such as China and Philippines are following a similar approach to the Indian one in this regard. Footnote 66

Egypt provides an interesting case as well. The country is home to the highest rate of HCV infections in the world. The Egyptian’s Patent Office practise won praise couple of year ago when it rejected one of Sofosbuvir patent applications through its application of a strict patentability criteria. This allowed a local generic producer to produce the drug for less than $200 per 12-week treatment. Footnote 67

Parallel importation is another flexibility already used by several countries with positive results. For example, six African countries (Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe) have incorporated an international exhaustion regime in their laws, allowing parallel imports from anywhere in the world. More specifically, Kenya has actively and effectively used parallel importation to improve access to antiretroviral medications. Footnote 68

Opposition procedures have been applied usefully and efficiently in several countries. This issue is posed to gain more importance due to the increased volume of pharmaceutical patents granted worldwide. To give a glimpse, it is believed that current estimates suggests that at least 27% of current patents would be found invalid by US courts due to low quality. Footnote 69

There are many more examples of the use of the flexibilities by both developed and developing countries which this chapter will not delve into. However, a number of observations could be made about the efficient and successful use and implementation of these flexibilities under national regimes. First, the need for a proactive national legislature is fundamental for the success of this process. Although these flexibilities are available under the international intellectual property regime, their implementation would not take place directly without legislating—in details—them under national laws and regulations. Second, awareness about the existence of these flexibilities is vital for their utilisation. Thirdly, the need for an engaged public, national entities and active civil society is essential for the success of this process as demonstrated by many thus far. Lastly, independent and highly trained judiciary is vital in the process of implementation and interpretation of these flexibilities under national legal frameworks.

6.3 The Shift Towards TRIPS-Plus

The TRIPS Agreement was subsequently used as a platform for further regulation of intellectual property rights globally. Although the initial understanding of developing countries was that TRIPS would put an end to unilateralism and coercion in the regulation and enforcement of intellectual property by developed countries particularly the United States, that vision turned out to be misguided. Within a short period of time following the creation of the TRIPS Agreement, a new generation of bilateral and regional Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) started to emerge, with a far-reaching WTO-Plus agenda.

With relation to intellectual property, FTAs often contained dedicated chapters incorporating extensive intellectual property provisions which often include TRIPS-Plus obligations going beyond those required by the TRIPS Agreement. These TRIPS-Plus obligations restricted the available policy space of member states and gradually eliminated the options and flexibilities available to them under the TRIPS Agreement. Footnote 70 Although the full impact of these TRIPS-Plus agreements is yet to materialise, we already have a considerable and rather frightening understanding—as will be explained in the next part of this chapter—about the negative impact these agreements have on affordability and accessibility to medicines.

6.4 Impact and Examples of TRIPS-Plus Obligations

Before looking into the negative impact of TRIPS-Plus, it would be helpful to understand how do FTAs increase intellectual property protection levels beyond the TRIPS standards? An important objective of TRIPS-Plus obligations is to limit the use of the flexibilities available under the international intellectual property regime thus making it more difficult to utilise such flexibilities. There are a number of areas where this may take place with relevance to patents and public health. These include the following examples:

Expanding the scope of pharmaceutical patents and creating new drug monopolies: this is achieved through a number of ways such as:

lowering the patentability standards,

requiring patents be available for surgical and treatment methods,

minor variations on old medicines, new and second uses, and Footnote 71

Further extension of protection to biological products which include vaccines, blood and blood components, and gene therapies in addition to other forms of protection.

Extension of monopolies by extending patent terms if review at the patent office or regulatory authority failed completion within a certain period of time.

Risk facilitating patent abuse by requiring countries to condition marketing approval on patent status (patent linkage).

Protection and Extension of “data exclusivity”: by providing at least 5 years exclusivity for information related to new products and 3 more in cases of new uses for old medicines—even when that information is disclosed and available in the public domain. More recent FTAs have also provided 10 years of “effective market protection” for biologics. Footnote 72

Prohibition/restriction pre-grant oppositions —forbid challenges to weak or invalid patents until after they have been granted.

Regulate the decisions to reimburse new drugs: this gives drug companies new rights to challenge decisions on reimbursements if not favourable as currently proposed under the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

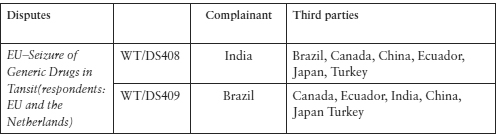

Require new forms of intellectual property enforcement–grant: customs authorities detaining shipments, including in-transit shipments, suspected of non-criminal trademark/copyright/patent infringements; require mandatory injunctions for alleged intellectual property infringements; raise damages amounts, etc.

Introducing Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) procedures: this leads to bypassing the WTO’s multilateral dispute settlement procedure and opting for a more pro-investment one. This development has been highly controversial as this grant private investors considerable power, especially big multinational corporations, to claim high amounts of money of compensation from investor sympathetic tribunals. Indirectly, this questions the impact of these claims on states’ power to regulate in the public interest, in order to safeguard public health priorities. Other flaws of the ISDS system include the lack of consistency in decision making and the huge costs incurred. There is now growing evidence that the threat of using these ISDS procedure is enough to obligate countries to change their policies. Footnote 73

The undisputed recommendation in this regard from a public health perspective remains that countries should avoid entering into arrangements which obligates them to apply TRIPS-Plus standards under national law. As states by UNDP and UNAIDS: Footnote 74

Countries at minimum should avoid entering into FTAs that contain TRIPS-plus obligations that can impact on pharmaceuticals price or availability. Where countries have undertaken TRIPS-plus commitments, all efforts should be made to mitigate the negative impact of these commitments on access to treatment by using to the fullest extent possible, remaining public health related flexibilities available.

The thus far realised impact of TRIPS-Plus obligations on public health and access to medicines is frightening upon both developed and developing nations. Footnote 75 In one of the first studies ever conducted on the impact of TRIPS-Plus obligations, a 2007 Oxfam study on the effect of the US-Jordan FTA found that since 2001 (which is the year the FTA was signed with the US), the prices of medicines in Jordan have increased by 20% (this led to price increases between two and ten-fold for key medicines to treat cardiovascular disease and cancer), and data protection provisions has resulted in delaying generic drugs entry for 79% of medicines newly launched between the years 2002 and 2006. Footnote 76 The study estimates that the availability of generic equivalents would have reduced Jordan’s expenditure on medicines by $6.3 and $22 million between mid-2002 and 2006. Footnote 77 The study also shows that no real know-how transfer has occurred in the country despite the rhetoric that FTAs would in fact encourage the flow of know-how and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI).

Although the 2007 Oxfam study was conducted under less than 5 years of the FTA implementation, we came a long way since then in terms of assessing and understanding the impact of FTAs on accessibility and affordability of medicines. More and more studies are affirming and exposing the negative impact of these obligations on public health and access to medicines.

Amin and Keselheim conducted a study on the impact of ‘evergreening’ resulting from the granting of secondary patents. The authors concluded that secondary patents could extend market exclusivity and thus delay generic competition from entering the market for many years. The study identified 108 patents related to two HIV medicines (ritonavir (Norvir) and lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra)) which impact could delay generic competition until at least 2028. This is a twelve years additional period after the expiration of the patents on the drugs’ base compounds and thirty-nine years after the first patents on ritonavir were filed. Footnote 78

For instance, research by Lexchin concluded that extension of legal protection in data protection for biologics have resulted in increase in spending in drug expenditure in Canada. He estimated the lost savings from data protection extension to range from $0 to $305.8 million. Footnote 79 Another study in Australia found: Footnote 80

At the time that the EOT [extension of the term] was introduced, the annual cost to the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS) was estimated to grow from $6 million in 2001-02 to $160 million in 2005-06. This cost arises because there is a delayed entry to the PBS of cheaper generic drugs. The estimate for 2012-13 is around $240 million in the medium term and, in today’s dollars, around $480 million in the longer term. The total cost of the EOT to Australia is actually about 20 per cent more than this, because the PBS is only one source of revenue for the industry.

Another study conducted by the Australian Generic Medicines Industry Association analysed the costs to the health system for 39 PBS-listed medicines for which generic competition was delayed after the patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient expired, as a result of secondary patenting found that in the 12 months to November 2012, the cost of delayed generic launch was calculated at $37.8–$48.4 million. Footnote 81 This estimate does not include subsequent price reductions due to price disclosure. Another study estimated the costs of patent extensions to the PBS in 2012–13 at about $240 million in the medium term and about $480 million in the longer term. Footnote 82 It was also found that data protection had no impact on the levels of pharmaceutical investment in the country as highlighted with the case of the US FTA with Jordan.

There has been much more work conducted recently in terms of alerting to the negative impact of the highly controversial Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) agreement in this regard. Footnote 83 The TPPA which is widely promoted as a “model for 21st century trade agreements” is a comprehensive trade and investment deal covering many areas including trade, investment, labour and intellectual property rights in in addition to its investor-state dispute settlement procedure. Footnote 84 Brook concludes that ‘Provisions in the Intellectual Property (IP) Chapter of TPP lengthen, broaden, and strengthen patent-related monopolies on medicine and erect new monopoly protections on regulatory data as well. IP Chapter enforcement provisions also mandate injunctions preventing medicines sales, increase damage awards, and expand confiscation of medicines at the border’. Footnote 85

In comparing the TPPA with similar agreements, a study found that the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s (USMCA) intellectual property chapter is closely based on the corresponding chapter of the TPPA, but includes 10 years of “effective market protection” for biologics in addition to including a broader definition of biologics, potentially expanding the array of drugs which will be eligible for this longer period of exclusivity, longer than the period negotiated in the TPPA. Footnote 86 For Canada, this will increase the period of market protection for biologics by 2 years; two studies of the potential impact on pharmaceutical expenditure (using different methods and based on different assumptions) have estimated the savings foregone at between CDN$0 and $305.8 and up to CDN$169 by 2029. Footnote 87

7 What Could Be Done and What Is Done?

As explained, we have a considerable wealth of empirical research about the positive impact of TRIPS flexibilities use and the negative impact of TRIPS-Plus obligations on the health care and access to medicines regimes in several developed and developing countries. However, it has been more difficult to observe how countries with TRIPS-Plus regimes have in fact attempted to utilise the remaining policy space available to them in order to mitigate the negative impact these TRIPS-Plus rules have on their national health care regimes. This is so primarily due to the difficulty in observing national practises and the lack of international jurisprudence arising from disputes about the implementation of these obligations (or rather about if such an implementation was in line with international norms or otherwise) under national frameworks.

In addition, it should be realised from the outset that the effect of TRIPS-Plus commitments will vary from each country and will depend on many factors, including market side, pharmaceutical protection capacity, development of legal regime, judiciary and so forth.

Nevertheless, and despite the above-mentioned difficulties, by looking into several cases, we have been able to observe some important contributions in this regard. The important aspect in this case is to continue applying and implementing a nationally creative thinking and interpretive policy aimed towards limiting the negative impact of the committed TRIPS-Plus rules. Following are examples of a number of national experiences of how countries attempted to limit the negative impact arising from TRIPS-Plus obligations.

7.1 Australia

One of the countries which have taken several serious steps in this field is Australia. This is because the country has agreed to a TRIPS-Plus obligations regime arising from the US-Australia FTA Footnote 88 which had a huge cost on the national health budget and the accessibility and affordability of medicines. Accordingly, in 2013, Footnote 89 the Australian legislator (following national consultation) introduced a number of reforms aimed towards mitigating the effects of the ‘evergreening’ of patents starting with applying a stricter patentability criteria by removing any geographical limitation upon the common general knowledge and by removing the requirement for a prior art document to be “ascertained”. Footnote 90 The effect of this is to require a higher and more consistent inventive step standard for Australian patents granted in the country.

Another area tackled by the Australian legislator is the issue of patent term extension granted in order to compensate for the delays during marketing approval as dictated under the FTA with the US. Footnote 91 To start with, the 2013 Patent Law reform attempted to limit the possibilities of allowing patent term extension by further confining such type of extensions to certain and specific categories of products related to patents claiming new active ingredients or formulations only. Footnote 92

Moreover, the Australian 2013 Patent Law reform imposes additional substantive conditions specifically applicable for the extension of patent duration for “pharmaceutical substances.” Based on this, the extension of the term is possible only if either or both of the following conditions are satisfied: Footnote 93

one or more pharmaceutical substances per se must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification;

one or more pharmaceutical substances when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, must in substance be disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance fall within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

In addition, both of the following conditions must be satisfied in relation to at least one of those pharmaceutical substances:

goods containing, or consisting of, the substance must be included in the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods;

the period beginning on the date of the patent and ending on the first regulatory approval date for the substance must be at least 5 years.

(4) The term of the patent must not have been previously extended under this Part. Meaning of first regulatory approval date.

More reforms were introduced with relation to opposition procedures as well. As such, detailed and expansive opposition grounds against patent term extension procedures were included under the 2013 Patent Law reform. Accordingly, Article 78 of the Patent Law states:

If the Commissioner grants an extension of the term of a standard patent, the exclusive rights of the patentee during the term of the extension are not infringed:

by a person exploiting:

a pharmaceutical substance per se that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification; or

a pharmaceutical substance when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification; for a purpose other than therapeutic use; or

by a person exploiting any form of the invention other than:

a pharmaceutical substance when produced by a process that involves the use of recombinant DNA technology, that is in substance disclosed in the complete specification of the patent and in substance falls within the scope of the claim or claims of that specification.

Patent linkage is another TRIPS-Plus issue whereby Australia’s approach may provide some valuable lessons for others. Article 17.10.4 (in the Intellectual Property chapter) of the US-AUS FTA provides for an attenuated or ‘weak’ form of patent linkage with relation to two aspects as explained by Son et al: Footnote 94

measures in the marketing approval process to prevent a third party from marketing a product during the term of a patent without the consent of the patent owner; and

no provision for the owner to be notified of a marketing approval request made during the term of a patent. This wording provided scope for Australia to implement a patent linkage mechanism in a very different way to the United States.

In addition, the Australian regime excludes from protection patents covering (1) the drug substance, (2) the drug product including composition and formulation, and (3) the approved use from the patent linkage mechanism. Footnote 95 Penalties for providing false or misleading information, however, are disproportionately higher for a patent holder certificate than for a generic producer certificate. Moreover, Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS) imposes automatic and irreversible price cuts on medicines as soon as competing versions enter the market, this often incentivise generic companies to launch faster at risk, and innovator companies must pursue preliminary injunctions in order to resolve patent disputes. Footnote 96 At the same time, since 2012, Australia’s Department of Health has pursued market-sized pecuniary damages (on top of those sought by the generic company) aimed at compensating for a delay in the PBS price reduction that would have been applied to a patented medicine during the period of a provisional enforcement measure. Footnote 97 However, there is no corresponding mechanism for the government to compensate innovators for the aforementioned losses if an infringing product is launched prematurely. Footnote 98

Although such reforms are vital, they should not be viewed as the only solutions to the accessibility of medicines challange and therefore the intellectual property regime should be viewed as one of several components and government strategies—one element of an eco-system—in this regard which would improve accessibility and affordability of medicines. For an example, in February 2019, the Australian government signed a five-year deal with pharmaceutical companies, involving a lump sum payment of about $ 766 million for an unlimited five-year supply of the most advanced Hepatitis C (HCV) drugs. Footnote 99 This innovative approach which has been called the “subscription” or “Netflix” model, have reduced the per-patient costs of these cutting-edge treatments by roughly 85% in the country. Footnote 100

Chile also proved an interesting case of a developing country which adopted a TRIPS-Plus regime as a result of signing an FTA with the US in 2006 (the US-Chile FTA). Following a rigorous national debate with relation to the negative effect of data exclusivity and patent linkage included under the FTA, the Chilean government amended the patent law by limiting the availability of data protection under its national law to those pharmaceutical products that have been marketed in the national territory in the year after the grant of marketing approval and therefore if the drug was not marketed within a year, the test data submitted for approval purposes will not be protected. Footnote 101 The rationale behind such a requirement is to encourage early registration of drugs after first registration abroad, so that the period of protection for the pharmaceutical test data starts early.

In addition, the law excluded several elements from the scope of protection. Accordingly, article 91 of the Chilean law states:

The protection of this Paragraph shall not apply when:

The owner of the test data referred to in Article 89 has engaged in forms of conduct or practices declared as contrary to free competition in direct relation to the use or exploitation of that information, according to the final decision of the free competition court.

For reasons of public health, national security, non-commercial public use, national emergency or other circumstances of extreme urgency declared by the competent authority, ending the protection referred to in Article 89 shall be justified.

The pharmaceutical or chemical-agricultural product is the subject of a compulsory license, according to what is established in this Law.

The pharmaceutical or chemical-agricultural product has not been marketed in the national territory after 12 months from the health certificate or clearance granted in Chile.

The pharmaceutical or chemical-agricultural product has a health certificate

Furthermore, Chile implemented the linkage obligation established by the US-Chile FTA through the provision of information to the patent owner about a third party intending to commercialize a product with similar characteristics to one that is already patented. Footnote 102

The aim of these measures is to explore whatever policy space remains available to the country in order to restrict the application of data exclusivity.

7.3 What Others Are Doing and How They Are Doing It?

There are many examples of interpretations and flexibility use taking place regularly in different parts of the globe. Footnote 103 These developments are either legislative, administrative or judicial in nature. Calls are made for countries to take advantage of the remaining policy space in this regard and share their experiences with others. Following are some non-exhaustive recommendations.

Several recommendations were made more with connection to data exclusivity obligations. As a result, it is advisable for those regimes’ committing to TRIPS-Plus data exclusivity provisions not to grant protection unless a specific application is made (within a specific period—no more than 6 months—of time after the first approval in the world of a medicine) and where certain conditions are met. Countries may also charge for these applications and require annual maintenance fee (such as those applicable to trademarks). In addition, detailing when protection will terminate is recommended. Correa suggests the following situations as examples: Footnote 104

When the right-holder or a person authorised by him does not commercialise the approved product in a manner sufficient to supply the demand within a period (e.g. twelve months) from the date of approval for commercialisation or when the commercialisation is interrupted, for more than x consecutive months (e.g. six months), except in cases of force majeure or government’s acts that prevent such commercialisation.

For public interest reasons such as national security, emergency or circumstances of extreme urgency that justify the termination of the period of exclusivity.

When, as a result of administrative or judicial procedures, it is determined that the right-holder has abused his rights, for example, through practices declared as anticompetitive.

Keeping health out of the FTA agenda is one right step in this regard. We can observe some positive steps taken in this area. The recently concluded FTA between Australia and Peru have explicitly excluded public health measures and/or specific health programs from its scope. Article 8. 16 of the FTA states: Footnote 105

Nothing in this Chapter shall be construed to prevent a Party from adopting, maintaining or enforcing any measure otherwise consistent with this Chapter that it considers appropriate to ensure that investment activity in its territory is undertaken in a manner sensitive to environmental, health or other regulatory objectives.

Compulsory licensing in TRIPS agreements is stated with ambiguous wording such as ‘national emergency’, ‘other circumstances of extreme urgency’, and ‘public non-commercial use’. To deal with this ambiguity, active interpretations of these terms should be persued. In this context, the Thai experience is noteworthy. The legislator there defined public non-commercial use as ‘nutrition and public health service’ and ‘protection of natural resources and environment’. Also, the legislater interpreted the non-use of a patent as ‘insufficient use of a patent due to the high price’ and ‘severe shortage of food and drugs’. Footnote 106

It is worth noting that the above referred to examples should not emanate from separate national initiatives but rather as a part of a more comprehensive approach dealing with public health challenges within these countries. As seen, several developed countries acknowledge today the negative consequences to TRIPS-Plus rules on public health and have taken steps to rectify the situation. Developing countries should follow suit and take serious notice of such implications.

8 Final Thoughts

The world is at a crossroads. At the time of completion of this chapter, the world was struggling in confronting the outbreak pandemic of the Corona virus (Covid-19). Although several vaccines are available today, the daily loss of life is having grave ramifications for the global economic and public health regimes. These outbreaks are not new, however how we deal with them will depend on our ability to access and grant funding for those working around the clock to find a cure. The intellectual property regime needs reorientation to become truly an incentive rather than an impediment to accessibility and treatment.

Some final thoughts could be made here with relation to supressing the impact of TRIPS-Plus conditions on access to medicines within the framework of trade and investment agreements. First, comprehensive assessment of the health impact of FTAs and TRIPS-Plus commitments should be undertaken by policy makers and negotiators. This should take place before an agreement is entered into. Second, public and stakeholder engagement and collaboration is needed and should be a priority. A national intellectual property committee with authorities and mandates should be tasked with implementing a balanced national intellectual property Agenda. Alternative and new business models for research and development are needed to achieve better pricing of medicines. Push, pull and pooling strategies should be given more thought and experimented with in this regard. Footnote 107 Finally, transparency in drug pricing is pivotal to ensure that (i fair compensation is granted to those who invest in finding medical solutions to diseases, and (ii affordable drug prices are applied so that patients can afford them. The 2019 World Health Assembly’s resolution supporting greater public disclosure of prices for medicines and other health products is a step in the right direction. Footnote 108

The legal recommendation stands today the same as before; governments should resist accepting and introducing TRIPS-Plus obligations even if others do so. At the same time, those who committed to such obligations should undertake a thorough review in order to identify areas where they can still utilise the TRIPS Flexibilities. We may not be able to stop the spread of TRIPS-Plus commitments around the globe; however, we should try and do our best to slow down the process of eroding the remaining policy space.

It should be highlighted that there are also other regulatory regimes and intellectual property exclusivities—apart from patents—aimed towards extending protection including those protecting use of test data, various regulatory linkages, and also trademarks covering not just names but also shapes and colours.

MSF ( 2016 ). http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s23020en/s23020en.pdf .

In 2019 more than 50 companies raised the prices on hundreds of drugs in the US by an average of more than 6%, according to the analysis. Hopkins explains that the price of rheumatoid arthritis treatment Humira, the world’s top-selling drug, was raised by 7.4%. Similarly, heparin products—which are generic blood thinners typically administered in hospitals—prices rose by 15%. For more see Hopkins ( 2020 ) < https://www.marketwatch.com/story/drug-prices-rise-58-on-average-in-2020-2020-01-02 >.

Gallup and West Health ( 2019 ). https://news.gallup.com/poll/268094/millions-lost-someone-couldn-afford-treatment.aspx?version=print .

The King’s Fund ( 2018 ) https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-04/Rising-cost-of-medicines.pdf .

WHO ( 2018 ), p. xi https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/277190/9789241515115-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y .

Sciences Avenir with AFP ( 2015 ). http://www.sciencesetavenir.fr/sante/cancer/20151216.OBS1499/la-ligue-contre-le-cancer-denonce-les-prixexorbitants-des-medicaments-innovants.html .

Raffi and Reynes ( 2014 ), p. 1158.

I-MAK ( 2017 ).

Boseley ( 2015 ) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/jan/16/sofosbuvir-hepatitis-c-drug-nhs .

Gornall et al. ( 2016 ), p. 4117.

Entis ( 2019 ).

The Economist ( 2019 ).

Donnelly ( 2015 ). The article further identifies that in total, 17 cancer drugs for 25 different indications will no longer be paid for in future in the UK.

According to January 2019 NHS England data, almost 25% of cancer patients didn’t start treatment on time despite an urgent referral by their primary care doctor. This represents the worst performance since records began in 2009. For more see Pipes ( 2019 ). https://www.forbes.com/sites/sallypipes/2019/04/01/britains-version-of-medicare-for-all-is-collapsing/#4c6ebeb736b8 .

WHO ( 2015 ), p. 5 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/193736/1/9789241509763_eng.pdf . However, it was announced in late 2019 that a new antibiotic for drug-resistant tuberculosis—pretomanid was finally approved by the FDA. Interestingly, the drug was developed by the non-profit TB Alliance rather than the industry. For more see Dearment ( 2019 ) https://medcitynews.com/2019/08/new-antibiotic-for-drug-resistant-tuberculosis-scores-fda-approval/ .

The two WHO reports cited below also found that research and development for antibiotics is primarily driven by small- or medium-sized enterprises with large pharmaceutical companies continuing to exit the field. For more see WHO ( 2017 ) https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258965/WHO-EMP-IAU-2017.11-eng.pdf?sequence=1 , and WHO ( 2019 ) https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/330290/WHO-EMP-IAU-2019.12-eng.pdf .

O’Neill ( 2015 ).

Trouiller et al. ( 2002 ), p. 2188.

Pedrique et al. ( 2013 ), p. 371.

See MSF ( 2016 ).

See MSF ( 2016 ), p. 8.

For more see Herder et al. ( 2020 ), pp. 1–14.

Røttingen et al. ( 2013 ), p. 1286, also see MSF ( 2016 ).

Rowland ( 2019 ).

Stevens et al. ( 2011 ), p. 535.

Global Justice Now and Stop AIDS ( 2017 ), p. 7. https://www.globaljustice.org.uk/sites/default/files/files/resources/pills-and-profits-report-web.pdf .

Ibid at 10.

Mole ( 2019 ) https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/02/drug-companies-are-sitting-on-generics-43-of-recently-approved-arent-for-sale/ .

It should be noted that the product lifecycle management starts at the development and regulatory approval stages and extends beyond the expiry of the granted patent. Notably, drug manufacturers do not only rely on patent protection when devising their lifecycle strategies. For example, reliance on trademark protection and branding is also vital in providing effective means to secure and maintain a strong market position. For more on this see Dutfield ( 2020 ). file:///C:/Users/melsaid/Downloads/Not_Just_Patents_and_Data_Exclusivity_Th.pdf.

I-MAK identifies the following three multi-billion-dollar drugs as having questionable patents that are providing excess exclusivity periods:

Revlimid® (lenalidomide): Unmerited patents enable a minimum exclusivity period from 2019 through 2028. Payers are projected to spend $45 billion in excess costs for the drug within this period, prior to the first generic product entering the market.

Sovaldi® (sofosbuvir): Unmerited patents will prevent competition from now through 2034, when final patents held by Gilead Sciences expire on the drug. Payers are projected to incur $10 billion in excess costs.

Gleevec® (imatinib): In the one-year period from 2015–16, approximately $700 million dollars in excess costs were passed onto payers as a result of a pay-for-delay deal cut by Novartis to a generic company in exchange for delaying the entry of generic imatinib.

For more see I-MAK ( 2017 ).

The majority of these patents focuses on developing so-called ‘me-too’ drugs—medicines which have only small clinical advantages over existing drugs, but which can be patented and bring substantial profits. The effects of evergreening vary but the primary impact would be to extend the monopoly term granted to patents. For more see Kesselheim et al. ( 2006 ), p. 1637.

Amin and Kesselheim ( 2012 ), p. 2286.

I-MAK ( 2018a ) http://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/I-MAK-Overpatented-Overpriced-Report.pdf .

I-MAK ( 2018b ). http://www.i-mak.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/I-MAK-Lantus-Report-2018-10-30F.pdf .

Amin and Kesselheim examined patents granted for two HIV drugs (ritonavir and lopinavir/ritonavir) and found that Abbott owned 82 secondary patents and had a further 26 pending applications in the US, all of which involved small variations on the original patents for these drugs. They found that these evergreening patents could delay generic competition for 19 years beyond the date from which generic entry would have been anticipated. For more see Amin and Kesselheim ( 2012 ).

Christie et al. ( 2013 ), p. e60812.

Office of Patented Medicines and Liaison ( 2005 ).

EU Commission ( 2008 ), p. 10. https://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/pharmaceuticals/inquiry/communication_en.pdf .

Prescrire International ( 2005 ), pp. 68, 71.

Light and Warburton ( 2016 ), p. 34.

Ward et al. ( 2014 ), p. 6235.

Drahos ( 2010 ).

See generally Machlup and Penrose ( 1950 ), p. 1.

See El Said ( 2010 ).

See the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Apr. 15, 1994, Marrakesh Agreement Establish the World Trade Organization, Annex 1C, 1869 U.N.T.S. 299 [hereinafter TRIPS Agreement] (listing the limitations on use of intellectual property by third parties authorized by the government).

There is a general differentiation in the literature between expressly provided safeguards, limitations/exceptions and countervailing legal principles and objectives on the one hand, and vague terminology on the other hand where there are provisions and omissions whose scope is subject to a wide range of interpretations in accordance with national and international legal regimes. For more see El Said ( 2010 ).

See the Council for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Extension of the Transition Period under Article 66.1 of the TRIPS Agreement for Least Developed Country Members for Certain Obligations with Respect to Pharmaceutical Products, Decision of the Council for TRIPS of 6 November 2015.

In 2019, Uganda notified the African Regional Intellectual Property Organisation (ARIPO) that it is exercising its right as a least-developed country by stating that pharmaceutical inventions are not eligible for patent protection in the country. See ‘t Hoen ( 2019 ). https://medicineslawandpolicy.org/2019/10/uganda-tells-aripo-no-more-patents-for-pharmaceuticals/ .

The special compulsory licensing system in the amended TRIPS Agreement, and the earlier 2003 waiver decision, (sometimes called the “Paragraph 6 System” because it refers to paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration) only deals with compulsory licences to produce medicines expressly for export purposes.

See TRIPS Agreement, Article 6.

See TRIPS Agreement, Art. 30.

This important exception facilitates the production and introduction of generic medicines into the market on the date of patent expiry. Accordingly, this exception permits the use of an invention for the purpose of obtaining approval of a generic product before the patent actually expires and without having to obtain the patentee’s approval. The WTO ruled that the use of this exception is TRIPS-compliant. For more see the WTO ( 2000 ).

See TRIPS Agreement, Art. 27.

‘t Hoen et al. ( 2018 ), pp. 185–193.

For more see El Said ( 2014 ), p. 60.

See number of compulsory licenses issued in ‘t Hoen et al. ( 2018 ), p. 188. However, it should be kept in mind that the ability to use compulsory licensing is not an available option to all countries equally but is rather more relevant to those which possess manufacturing capabilities.

For more see Ling ( 2019 ). http://english.astroawani.com/malaysia-news/using-compulsory-licence-affordable-medicines-200558 .

The issued compulsory license were for three ARV medicines namely Ritonavir+Lopinavir and Lamivudine+Abacavir, for Etoricoxib (Arcoxia® for the treatment of diseases with acute pains); Mycophenolate Sodium (MYFORTIC) used in the treatment of reception of kidney transplants; sunitinib, an anticancer drug used for the treatment of carcinoma renal cells (CRC) and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs); and finally Certolizumab, used to counteract rheumatoid arthritis. See Correa and Velásquez ( 2019 ), p. 16. https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/RP85_Access-to-Medicines-Experiences-with-Compulsory-Licenses-and-Government-Use-The-Case-of-Hepatitis-C_EN-1.pdf .

For more see El Said ( 2016 ), p. 374.

See Chatterjee ( 2013 ). https://www.ip-watch.org/2013/04/01/novartis-loses-patent-bid-lessons-from-indias-3d-experience/ .

See Sampat and Shadlen ( 2017 ), p. 693.

Other countries are increasingly following India’s patentability path. The Philippines patent law, as amended in 2008, introduced a section similar to the Indian 3(d) section (although less stringent than India’s Patent Act).177

China has reformed its Patent Act in 2008 and 178. See Patent Law (promulgated by the Standing Comm. Nat’l People’s Cong., Mar. 12, 1984, rev’d Dec. 27, 2008 ), art. 22. For more see El Said ( 2016 ).

Velasquez ( 2019 ), p. 108.

UNAIDS ( 2011 ), p. 15. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2260_DOHA%2B10TRIPS_en_0.pdf .

Miller ( 2012 ). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2029263 .

See Drahos ( 2001 ), p. 791 and El Said ( 2005 ), pp. 53–66.

For more on this from an EU perspective please see Dutfield ( 2017 ), p. 453.

Ney ( 2019 ). https://www.centerforbiosimilars.com/contributor/joshua-ney/2019/08/exclusivity-for-biologic-products-under-the-usmca-what-is-changing-and-what-happens-next .

For instance, in 2016; and Ukraine de-registered a generic hepatitis C medicine after Gilead indicated that it would pursue arbitration. For more see Gleeson et al. ( 2019 ), p. 78.

UNDP and UNAIDS ( 2012 ) https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2349_Issue_Brief_Free-TradeAgreements_en_0.pdf .

Oxfam ( 2007 ), p. 5 https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/114080/bp102-all-costs-no-benefits-trips-210307-en.pdf%3Bjsessionid%3D089750820CF675173F0C3204C369D63F%3Fsequence%3D1 . Also see El Said ( 2006 ), p. 501.

Oxfam, Ibid.

See Amin and Kesselheim ( 2012 ).

Lexchin ( 2019 ), p. 10.

Harris et al. ( 2013 ), p. vi https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2013-05-27_ppr_final_report.pdf?acsf_files_redirect . The Report found that about 58% of new molecules listed on the PBS from 2003 to 2010 received extensions of term. Of the term extensions granted since 1999, 47% received the full 5 years.18 The cost of these extensions to the PBS in 2012–13 was estimated at about $240 million in the medium term and about $480 million in the longer term.

Gleeson et al. ( 2015 ), p. 306.

Harris et al. ( 2013 ).

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) issued a letter in 2019 to signatories of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement that the United States has formally withdrawn from the agreement.

The TPP is the first trade agreement to include provisions on pharmaceuticals that are, or contain, biologics, compounds produced through biological processes and which are used primarily for treating cancer and immune conditions.

Baker ( 2016 ), p. e1001970.

Swanson ( 2019 ). https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/21/us/politics/nafta-drug-prices.html .

Gleeson et al. ( 2015 ).

The US-Australia Free Trade Agreement (US-AUS FTA) signed in 2004.

Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 No. 35, 2012 as amended. Start date15 April 2013, hereafter the 2013 Patent Law.

Dixon ( 2017 ).

See US-AUS FTA, Art.17.9.8(b) states:

[E]ach Party shall make available an adjustment of the patent term to compensate the patent owner for unreasonable curtailment of the effective patent term as a result of the marketing approval process.

See El Said ( 2016 ).

See Patents Act 1990 (Cth) ch 6 pt 3 s 70 sub-divs (2)-(3) (Austl).

Son et al. ( 2018 ), p. 101.

GIPC ( 2019 ). https://www.theglobalipcenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/GIPC-Linkage-Zoom-In-Report.pdf .

Australian Government Department of Health ( 2016 ). http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/pricing/price-disclosure-spd/price-disclosure-operational-guidelines-06-2016.pdf .

GIPC ( 2019 ).

The government also announced an investment of more than 1 Billion USD to enable universal access to HVC treatment. See Velásquez ( 2017 ). https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/RP77_Access-to-Hepatitis-C-Treatment-A-Global-Problem_EN-2.pdf .

Moon and Erickson ( 2019 ), p. 607. Furthermore, the State of Louisiana announced in January 2019 that it was pursuing a similar approach for HCV. For more see Crisp ( 2019 ) https://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/politics/article_614e4f42-1523-11e9-8c90-4fcb305d17e8.html .

Law No. 19,039 art. 90, September 30, 1991 (modified on December 1, 2005 by Law 19,996, which classifies active ingredients as new chemical entities if they have not been marketed in the country prior to the health registration or authorization application). See also Biadgleng and Maur ( 2011 ), p. 20.

Correa remarks that on September 2nd, 2002 the Quinta Sala from the I Corte de Apelaciones (I Court of Appeals, Fifth Chamber) of Chile ruled that the Instituto de Salud Publica, which issues sanitary registries, ‘had no power whatsoever to either deny a marketing approval or to acknowledge rights derived from a patent’. See Correa ( 2017 ). https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/RP74_Mitigating-the-Regulatory-Constraints-Imposed-by-Intellectual-Property-Rules-under-Free-Trade-Agreements_EN-1.pdf . See also Chandler ( 2010 ), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1602883 .

See Correa ( 2017 ).

Correa ( 2017 ).

See the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Chapter 8: Investment. Peru-Australia Free Trade Agreement. https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/pafta/Pages/peru-australia-fta.aspx .

Kuanpoth ( 2006 ), p. 149.

See Suleman et al. ( 2020 ), p. 368. See also more generally the UN Secretary General High-Level Panel (n 1).

Fletcher ( 2019 ). https://www.healthpolicy-watch.org/world-health-assembly-approves-milestone-resolution-on-price-transparency/ .

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Apr. 15, 1994, Marrakesh Agreement Establish the World Trade Organization, Annex 1C, 1869 U.N.T.S. 299

Google Scholar

Amin T, Kesselheim A (2012) Secondary patenting of branded pharmaceuticals: a case study of how patents on two HIV drugs could be extended for decades. Health Aff 31(10):2286

Article Google Scholar

Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Chapter 8: Investment. Peru-Australia Free Trade Agreement. https://www.dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/in-force/pafta/Pages/peru-australia-fta.aspx . Accessed 3 Mar 2021

Australian Government Department of Health (2016) Pharmaceutical benefits scheme price disclosure arrangements: procedural and operational guidelines. http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/pricing/price-disclosure-spd/price-disclosure-operational-guidelines-06-2016.pdf . Accessed 3 Mar 2021

Baker B (2016) Trans-pacific partnership provisions in intellectual property, transparency, and investment chapters threaten access to medicines in the US and elsewhere. PLoS Med 13(3):e1001970