- International

Israel wages war on Hamas

1947 - 2024

O.J. Simpson dead

India-Pakistan: Latest news on Kashmir crisis

By Euan McKirdy , Bianca Britton and Eliza Mackintosh , CNN

Why does Kashmir mean so much to both India and Pakistan?

From CNN's Jack Guy, Katie Hunt and Nikhil Kumar

India and Pakistan have been locked in a struggle over Kashmir for more than 70 years, and the restive region is back in the news again this week.

So why does the mountainous region mean so much to the two countries?

Kashmir initially remained independent and was free to accede to either nation. When the Hindu king of Kashmir chose to join India in exchange for military protection, Jammu and Kashmir state became the only Muslim-majority state in the country.

Jammu and Kashmir covers around 45% of Kashmir, in the south and east of the region, while Pakistan controls Azad Kashmir, Gilgit and Baltistan -- which cover around 35% of the total territory in the north and west. Both countries claim complete ownership of Kashmir; also in the picture is China, which controls around 20% of Kashmir territory known as Aksai Chin.

The issue is also one of the oldest items on the agenda at the United Nations, where India and Pakistan took their dispute soon after independence.

Both countries agreed to a plebiscite in principle, to allow Kashmiris to decide their own future, but it has never been held because it was predicated on the withdrawal of all military forces from the region, which has not happened even decades on.

Indian authorities wanted to show that they could guarantee the rights of Muslims in a secular state, but Kashmir is also key to Pakistani identity as a homeland for Muslims after partition in 1947, said Simona Vittorini, a specialist in South Asian politics at SOAS University of London.

Read more on that here .

Pakistan says four civilians killed by Indian shelling

From CNN’s Swati Gupta in Delhi and Adeel Raja in Islamabad

Pakistan’s military says four of its civilians are dead and two others injured as a result of cross-border fire from India, a spokesperson told CNN.

Pakistan says it retaliated in response to India’s "deliberate firing on civilians." The most recent shelling by Pakistani artillery was in the Pani district of Pakistan-controlled Kashmir.

In a statement on cross border violence Thursday, Indian’s army accused Pakistan of initiating the attacks earlier this morning. The Indian statement said Pakistan fired mortars and small arms over the Line of Control and into the Krishna Ghati sector of Indian-controlled Kashmir.

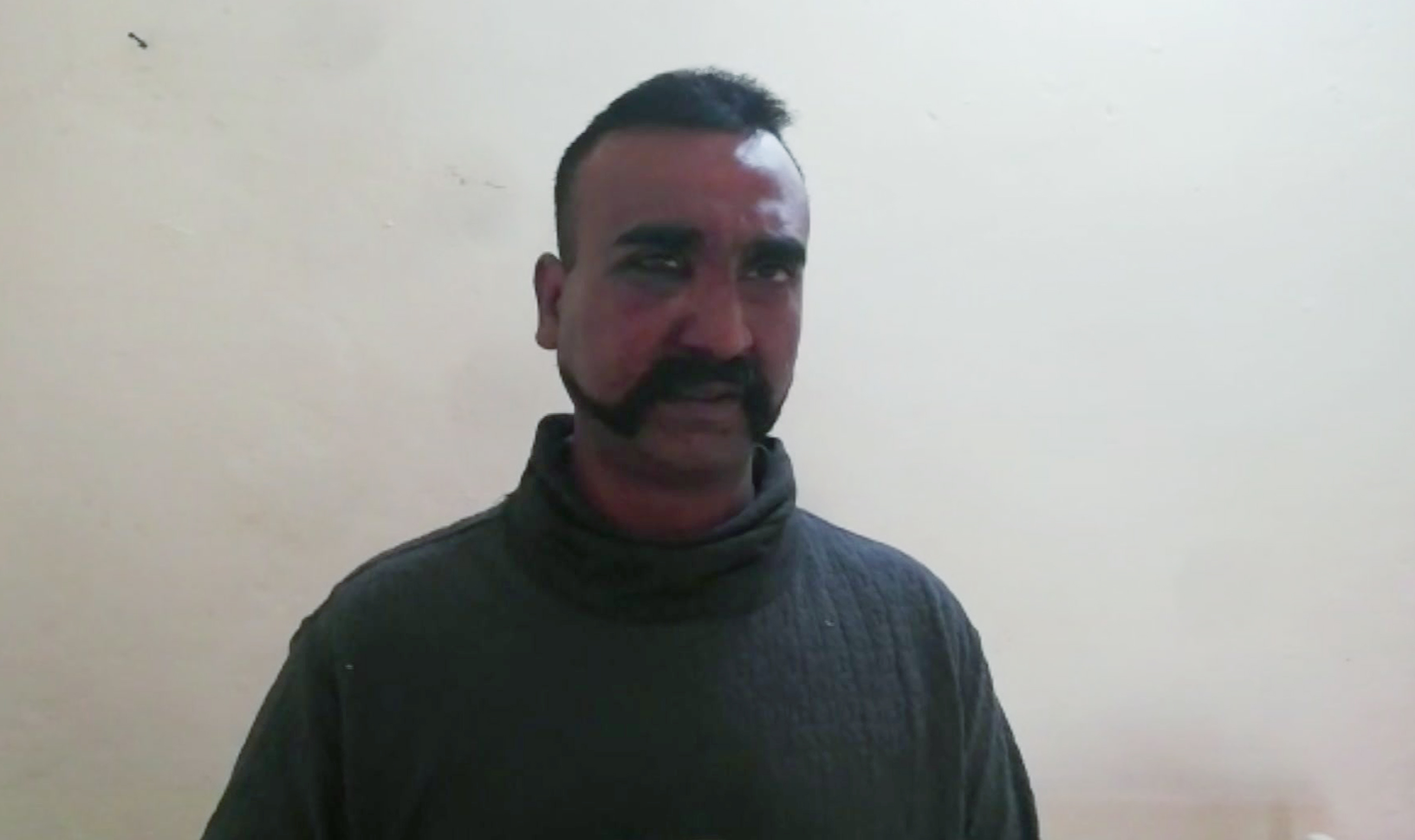

Pakistan to release detained Indian pilot

From Adeel Raja in Islamabad

Pakistan said that on Friday it would release the Indian pilot who has been in Pakistani custody since his plane was shot down on Wednesday.

“We are releasing the Indian pilot tomorrow as a gesture for peace,” Prime Minister Imran Khan said in a televised address Thursday.

What's the latest on Kashmir?

From CNN's Helen Regan

Just joining us? Here's what you missed.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made his first public comments since an Indian pilot was detained by Pakistan. Modi did not talk specifically about Pakistan or the pilot, instead, the prime minister spoke in general terms about trusting in the "army's capabilities" and working hard for the "prosperity of the country."

Meanwhile, hot off the heels of his summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, US President Donald Trump addressed the crisis in Kashmir and alluded to possible US attempts to deescalate the situation.

"They've been going at it, and we've been involved in trying to have them stop. And we have some reasonably decent news, hopefully that's going to be coming to an end," said Trump.

Pakistan's Finance Minister Asad Umar said that the country is "at the cross road of history" as tensions between the nuclear armed neighbors become increasingly fraught. While the Indian Minister of State for External Affairs, General Vijay Kumar Singh called for the release of the pilot who was taken into custody in Pakistan. Identifying him as Wing Commander Abhinandan, Singh described him as the “embodiment of a mentally tough, selfless & courageous soldier."

And there were severe disruptions to thousands of flights around the world as Pakistan closed its airspace for the second straight day. All international and domestic commercial flights in and out of Pakistan were canceled "until further notice" and Thai Airways announced that all its European routes were suspended. The airline later reopened its routes to Europe but Thai Airways flights to Pakistan remain canceled.

For more on the border crisis between India and Pakistan, here's analysis from CNN's Nic Robertson and Euan McKirdy .

Kashmir crisis is in the hands of two populist leaders with political agendas

By CNN's Nic Robertson

When two populists go to war, there is every chance their people will suffer more than they will.

These are the stakes that face both the recently-elected Imran Khan in Pakistan and Narendra Modi, of the Hindu Nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India, who is soon to face the electorate again.

To avoid escalating their current confrontation, the two prime ministers will have to face down the powerful pull of historic rivalries and mistrust, coupled with the more immediate needs of their own political careers.

Both countries say they don't want war.

Since they became nuclear powers, every time India and Pakistan have gotten to the point of toe-touching, eye-staring aggression the international pressure on them to step back from the brink has ratcheted up.

It's no different now, with the US, UK and even China imploring both countries to back off in the past 48 hours.

Read more analysis from CNN's Nic Robertson here.

With India tensions simmering, is Imran Khan ready for his first big political test as Pakistan’s Prime Minister?

Analysis by Euan McKirdy

During Pakistan’s general election last year, Imran Khan was dismissed by detractors as a political lightweight and foreign policy novice who relied on populism and deference to the country’s influential military for support.

Now, just over six months into his role as Prime Minister, those claims are being tested as Khan finds his country closer to war with its nuclear-armed neighbor, India, than at any point in the past 20 years.

Michael Kugelman, a South Asia expert at the US-based Wilson Center, said the crisis will likely give Khan’s popularity a boost.

“In Pakistan there’s nothing like aggression from India to rally the people,” he told CNN. “The fact that Pakistan had India come into the country to stage these airstrikes, it’s an embarrassment for the military. But the entire country will rally round Imran Kahn to support him.”

However, Kugelman said this is a political test for Khan, who formed his own party 23 years ago.

“He certainly is a neophyte, he has no experience as a national leader, he’s been a politician for a number of years but hasn’t been in a position of national power,” he added.

Read more analysis from CNN's Euan McKirdy here.

US President Trump addresses Kashmir, says situation 'coming to an end'

From CNN's Steve George

US President Donald Trump has addressed the crisis in Kashmir during a press conference in Hanoi.

"We have, I think, reasonably attractive news from Pakistan and India," said Trump, alluding to possible US attempts to deescalate the situation.

"That's been going on for a long time. Decades and decades. There's a lot of dislike, unfortunately, so we've been in the middle trying to help them both out, and see if we can get some organization and some peace, and I think, uh, probably that's going to be happening."

Indian PM makes speech but doesn't mention Pakistan

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said "the entire country is one and is standing with our soldiers."

Speaking in a video conference with campaign workers from his ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Modi did not talk specifically about Pakistan or the pilot who was shot down and is currently in custody in Pakistan. Instead, the prime minister spoke in general terms about trusting in the "army's capabilities" and working hard for the "prosperity of the country."

"The world is watching our collective will. We trust our army’s capability and because of this, it is extremely necessary that nothing should happen that harms their morale or that our enemies should get a chance to raise a finger against us," he said.

"When our enemy tries to destabilize the country, when terrorists attack – one of their goals is that our progress should stop, our country should stop moving ahead. To stand up against this aim of theirs, each Indian should stand like a wall or a rock. We have to show them that neither will this country stop, nor will the country’s progress slow down."

“India will live as one, India will work as one, India will grow as one, India will fight as one, India will win as one," he said.

Pakistan 'at the crossroad of history'

Pakistan's Finance Minister Asad Umar said that the country is "at the cross road of history" as tensions between nuclear armed neighbors India and Pakistan become increasingly fraught.

"Leadership of India & Pak need to decide if we want to lead our nations towards peace & prosperity or conflict," he said in a post on his official Twitter account Thursday.

He added that Pakistan "remained committed to peace while resolute in defense of our sovereignty."

Please enable JavaScript for a better experience.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

India and Pakistan at 75

For kashmiris, resolution to decades of conflict remains a distant dream.

Raksha Kumar

An Indian army soldier collects Indian national flags after a rally marking Indian independence in Sopore district, Baramulla, in Jammu and Kashmir, on Aug. 11. Nasir Kachroo/NurPhoto via Getty Images hide caption

An Indian army soldier collects Indian national flags after a rally marking Indian independence in Sopore district, Baramulla, in Jammu and Kashmir, on Aug. 11.

SRINAGAR, India — Kashmiri poet Zareef Ahmad, 80, has unmatchable energy. He talks animatedly and feels passionately about his past. His study is filled floor to ceiling with books in Urdu, English and Farsi — some of which he has authored.

Ahmad won India's highest award for literature. But one of his most prized books is a small notebook filled with handwritten notes in Urdu.

Carefully cataloged are exact dates and locations of the hundreds of chinar trees he has planted in various parts of Kashmir for over 30 years. "I have planted them in police stations, government offices and universities, where they can use its shade to cool off tensions," he says.

Zareef Ahmad looks at his notebook of tree notations in his home in Srinagar on May 11, 2022. He has planted hundreds of chinar trees over the years. "I have planted them in police stations, government offices and universities, where they can use its shade to cool off tensions," he says. Raksha Kumar /NPR hide caption

Zareef Ahmad looks at his notebook of tree notations in his home in Srinagar on May 11, 2022. He has planted hundreds of chinar trees over the years. "I have planted them in police stations, government offices and universities, where they can use its shade to cool off tensions," he says.

The Himalayan region he calls home — hailed for its picturesque alpine beauty — has been roiled by conflict for decades, with both India and Pakistan staking claim to it. When Indians mark 75 years of independence this month, Ahmad and others in Kashmir may feel there's not much to celebrate.

A painful history

Pakistan was created as a homeland for the Subcontinent's Muslims when it and India emerged independent from British-ruled India in August 1947. But Kashmir's Hindu maharaja decided his Muslim-majority princely state would join India after armed tribesman from Pakistan invaded the region in October 1947.

In this Nov. 9, 1947, file photo, Indian Sikh troops take up roadside positions on the Baramula Road to help force armed invaders from Pakistan further away from Srinagar in Kashmir. India and Pakistan fought a yearlong war over control of Muslim-majority Kashmir. The war ended with a U.N.-brokered cease-fire leaving Kashmir divided between the two young nations. Max Desfor/AP hide caption

In this Nov. 9, 1947, file photo, Indian Sikh troops take up roadside positions on the Baramula Road to help force armed invaders from Pakistan further away from Srinagar in Kashmir. India and Pakistan fought a yearlong war over control of Muslim-majority Kashmir. The war ended with a U.N.-brokered cease-fire leaving Kashmir divided between the two young nations.

A United Nations-brokered cease-fire ended those hostilities in 1949. But over the decades, the two nuclear-armed neighbors have fought other wars over Kashmir and there have been more crises. Today, both India and Pakistan administer some parts of the territory. In India, it's called Jammu and Kashmir, and in Pakistan, it's known as Azad (Free) Kashmir.

In India, Kashmir has become emblematic of the country's recent authoritarian slide under a Hindu nationalist-led government. In August 2019, India revoked Jammu and Kashmir's constitutionally guaranteed special status, canceling its partial autonomy. Indian troops poured into the streets, the internet in Jammu and Kashmir was shut down for an extended period into the following year, phone service was cut and the media were severely restricted.

Today, there is an uneasy calm in the valley. People fear speaking out in public, press freedoms have been limited and local politics is dysfunctional and unresponsive to Kashmiris' everyday needs.

"While Indians celebrate their independence from [British] subjugation, they must also introspect as to what kind of union gets created by force," says Mirza Saaib Beg, a Kashmiri human rights lawyer. "And whether such forced unions merit celebration."

Opportunities have faded for diplomatic solutions

Zareef Ahmad's generation, born before India's Partition, remembers a time when a resolution to the Kashmir conflict seemed to be within reach. They hoped to see a return to self-rule.

"Kashmir is a nationality of its own, a civilization of its own, with more than 5,000 years of history," Ahmad says.

He lives in the older part of Srinagar, the largest city in Indian-administered Kashmir. His home is in an area surrounded by a Sufi shrine, a Hindu temple and a gurudwara, a Sikh place of worship.

A houseboat on Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir, photographed sometime in the years between 1915 and 1919. Peter Charlesworth/LightRocket via Getty Images hide caption

A houseboat on Dal Lake in Srinagar, Kashmir, photographed sometime in the years between 1915 and 1919.

"Kashmir's was always a composite culture, until India and Pakistan were divided on religious lines. We saw religion become a huge part of our division only after the countries were born," says Ahmad.

He and his generation expected a resolution to come from diplomacy and dialogue. The newly created United Nations got involved. India and Pakistan were initially led by statesmen like Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan. Kashmiris had their own leaders who exuded promise.

But in successive decades, the opportunities for a diplomatic resolution died a slow, painful death.

Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (right) talks with Kashmir Prime Minister Sheikh Mohamed Abdullah, in New Delhi, India, in 1951. AP hide caption

Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (right) talks with Kashmir Prime Minister Sheikh Mohamed Abdullah, in New Delhi, India, in 1951.

in 1953, India dismissed and then jailed the most charismatic Kashmiri leader, Sheikh Abdullah , as Kashmir's prime minister. "We felt betrayed," says Ahmed.

A hoped-for referendum to decide Kashmir's future never came.

"We extended a hand of friendship to India, but it cut our palm," says Ahmad.

Insurgency and army response

These days, Ahmad considers himself lucky to live with his son and grandsons.

"Not many Kashmiris have the joy of seeing their offspring alive — let alone live under the same roof," he explains. Violence and bloodshed have claimed the lives of many younger Kashmiris.

In the late 1980s, Kashmir exploded because the central government rigged elections in the region, argues writer and senior researcher Alpana Kishore . "The chief minister had been summarily dismissed, a puppet regime had been put in his place," she says.

Indian security forces beat Muslim protesters at a demonstration during a curfew in Srinagar, Kashmir, in 1993. Demonstrators were protesting against the encirclement of the Hazratbal mosque by Indian soldiers. Doug Curran/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Indian security forces beat Muslim protesters at a demonstration during a curfew in Srinagar, Kashmir, in 1993. Demonstrators were protesting against the encirclement of the Hazratbal mosque by Indian soldiers.

Kashmiris lost faith in a secular, democratic India bit by bit, she says. The 1990s were arguably Kashmir's bloodiest years. According to official government figures, more than 1,700 were killed between 1990 and 2021 by armed guerilla fighters who are fighting the Indian state.

More than 150,000 people fled the area and resettled in other parts of India. While there are no official public figures on the number of people killed by India's security forces, Sweden's Uppsala Conflict Data Program puts the figure at around 19,000 for the same period.

"There have been so many bad memories in our schooldays, because those days, the violence was at its peak," said Shafkat Raina, Ahmad's godson, a documentary filmmaker who is 45 and grew up in Kashmir's restive Anantnag district.

He recalls ducking under the benches in his classroom as firing broke out between militants and the Indian army outside.

"Tension was not only in school, this tension followed us our whole life — whether it is married life or social life. It disturbed us, everywhere," he says.

As the militancy took on a religious color, most members of Kashmir's small Hindu population fled the region altogether, leaving behind jobs and property.

In light of the previous decades' diplomatic failures, many Muslim Kashmiris of Raina's generation believed for a time that a resolution to the Kashmir conflict could come from insurgency against India, with help from Pakistan.

Kashmiri youth illegally crossed de facto border, known as the Line of Control, into Pakistan to acquire weapons and to learn how to use them against the Indian military, which became a familiar presence in Jammu and Kashmir starting in 1990.

Militants "were praised. They were looked at like heroes," says Raina.

His neighborhood had two houses that militants occupied. "They used to come play cricket with us," he recalls.

"In the 1990s, there was great interest in Pakistan as a savior," says Kishore. "What happened [after the 1990s] is that [Kashmiris] understood that Pakistan is not going to go to war with India over Kashmir."

An uneasy "integration" with India

Those born in the 1990s or later are habituated with violence and conflict.

As India increased its military presence in Jammu and Kashmir, observers recorded an increase in torture and other human rights violations by security forces.

Indian paramilitary soldiers frisk a Kashmiri during a surprise check operation in Srinagar, on Jan. 18, 2022. Dar Yasin/AP hide caption

Indian paramilitary soldiers frisk a Kashmiri during a surprise check operation in Srinagar, on Jan. 18, 2022.

"Hundreds of civilians, including women and children, have been extrajudicially executed... Such killings and hundreds of deaths in custody — by far the highest in any Indian state — are facilitated by laws that provide the security forces with virtual immunity from prosecution," Amnesty International reported in 1995 .

Today, it's difficult to know how many Indian security forces are stationed in Kashmir. The Indian government doesn't publish numbers. But troops are visible on most streets and public squares.

Danish Rajab Jhat (left) and Insha Mushtaq Malik (right), both pictured here in Sedow, Kashmir, in 2016, each lost the vision in one of their eyes after they were hit by shotgun pellets fired by the Indian military. Thousands of Kashmiris have lost eyesight due to pellet attacks by the Indian military. Bernat Armangue/AP hide caption

Danish Rajab Jhat (left) and Insha Mushtaq Malik (right), both pictured here in Sedow, Kashmir, in 2016, each lost the vision in one of their eyes after they were hit by shotgun pellets fired by the Indian military. Thousands of Kashmiris have lost eyesight due to pellet attacks by the Indian military.

In a 2015 report , the Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society estimated that there were between 650,000 and 750,000 Indian soldiers in the region. It's one of the most recent estimates available, as leaders of JKCCS have since been arrested.

Reaching the Pulwama district, in southern Kashmir, from Srinagar means crossing dozens of army checkpoints and barricades.

"Imagine being stopped many times and being asked for identification before reaching your own home," says Aamir Ahmad Bund, 25, a law student and president of the Association of Pellet Survivors, an organization for Kashmiris who have rubber bullets lodged in their bodies. He is among thousands who have lost their eyes due to attacks by India's military.

Bund was protesting in his village in Pulwama in 2016 when security forces fired rubber bullets, he says. The bullet that hit his right eye blinded him in that eye.

"There are several [rubber bullets] still lodged in my body," he says, pointing at his arms, torso and legs.

"No one even asks us what we think is a resolution to this conflict," he says.

With Jammu and Kashmir's limited autonomy broken in 2019, the government declared that the conflict was resolved and the region's integration with the rest of India was complete.

But for many Kashmiris, it has come at too high a price.

" When God asks me what I have, I will say I only have the trees I planted," says Ahmad, the poet. "Everything else is transient."

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

In Pakistan-Held Kashmir, Growing Calls for Independence

By Maria Abi-Habib , Jalaluddin Mughal and Salman Masood

- Sept. 19, 2019

MUZAFFARABAD, Kashmir — In Pakistan-controlled Azad Jammu and Kashmir, the simple fact of the region’s name — with azad meaning free — is a declaration that Kashmiris here enjoy a liberty denied to their kin across the border, in the Indian-held portion of the disputed territory.

But even in Pakistan-held Kashmir, the message has been clear, residents say: No talk of independence will be allowed.

As an Indian crackdown on the other side of Kashmir has led to massive civil unrest and new calls for a Kashmir free from either India or Pakistan, local activists and officials say a parallel security operation is being pushed inside Pakistan.

Pakistan has long prided itself on being a champion for Kashmiris, who are predominantly Muslim. And the government has chastised India for suppressing calls for freedom in the portion of Kashmir that New Delhi controls.

But New York Times journalists who were granted rare access to Azad Jammu and Kashmir in recent days found a toughening Pakistani security response to a growing independence movement here.

Residents say the upwelling is rooted in fears that their ability to reunify has been slowly slipping away ever since India increased its control of the divided territory and Pakistan did little to stop it other than to offer negotiations that India refused.

The Pakistani crackdown also has another focus, locals say: As outrage over India’s move to end Kashmiri autonomy last month has galvanized militants, Pakistani officials fear they could face international sanctions if they don’t rein in the armed groups.

On both sides of the border, Kashmiris are expressing frustration that no one is on their side.

“Both countries have gone to war over Kashmir. But Kashmiris have never had a voice in any of these disputes,” said Abdul Hakeem Kashmiri, a prominent journalist in Muzaffarabad, the capital of Pakistani-held Kashmir.

“We love the Pakistani Army and the Pakistani people, but we have our own culture. And people know what the unspoken red line is: independence,” Mr. Kashmiri said.

Pro-independence demonstrations that once attracted dozens of protesters are now attracting thousands, residents say. In one case this month, some 5,000 Kashmiris tried to march to the Indian border in Poonch district in Azad Jammu and Kashmir, local police officials said. Protesters charged at Pakistani security officers while chanting, “We want freedom on this side and we want freedom on the other side,” and “Foreign oppressors, leave us alone.”

Police batons cracked into the protesters, halting their advance and leading to scuffles that left 18 demonstrators and seven Pakistani police officers wounded, officials said. The protests were barely covered in Pakistani media, and mobile phone and internet were cut off for awhile in the area. One military general dismissed the demonstrators as “Indian agents.”

Despite appeals from the political leadership of Pakistan-held Kashmir to stop marching to the border area, Kashmiris say they plan to press on. They have called for massive protests on the border with India on Saturday and in early October that are expected to be the biggest demonstrations yet.

“The independence struggle on both sides of the border is being suppressed,” said Anam Zakaria, the author of “Between the Great Divide: A Journey Into Pakistan-Administered Kashmir.”

“There is a frustration that they have been on the front line of the conflict and are pawns in this greater game between India and Pakistan,” she said.

Last month, India stripped the autonomy from the portion of Kashmir it holds and strengthened New Delhi’s hold on the territory, detaining local politicians and activists and imposing a curfew and communications blockade that has entered its second month.

The protests are channeling civilian anger at the “line of control,” the de facto border that splits Kashmir between India and Pakistan , slicing through valleys dotted with wildflowers and pine trees, down the middle of rivers and through entire towns.

Sheep graze over the heavily mined boundary. Shepherds accidentally cross it, oblivious to its contours, only to be shelled by Indian or Pakistani soldiers, or detained.

The line demarcates the point where, in 1947, Indian forces repelled invading Pashtun tribal fighters that Pakistan drew from its border area with Afghanistan — the beginning of a longstanding Pakistani strategy to use militant proxies to weaken its neighboring rivals.

Originally, the line of control was meant to be temporary, with plans for a referendum that would allow Kashmiris to choose whether to join India or Pakistan. That vote never happened, and now, after decades of fighting, many Kashmiris fear that the temporary boundary will become a hard border, dividing the territory permanently.

“Kashmiris are trying to take their fate in their own hands. We realize that we can only rely on ourselves,” said Haris Qadeer, a young Kashmiri who joined the protests and whose newspaper in Muzaffarabad was shut down in 2017 for its pro-independence stance.

“The line of control is what separates us, it is what makes us refugees in our own country,” Mr. Qadeer said.

The police force used against protesters this month was a “preventive measure,” said the president of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Masood Khan, saying that the police response was restrained compared with that used by Indian forces on the other side of the line, who he said at times open fire on protesters trying to cross the border, resulting in serious injuries.

“There is a high degree of tolerance for dissent. There is an overwhelming pro-Pakistan sentiment in Azad Kashmir and Indian-occupied Kashmir,” Mr. Khan added.

But Kashmiri nationalists are forbidden in government. Elected officials like Mr. Khan must sign a declaration before they can run for office stating that they “believe in the ideology of Pakistan” and in Kashmir’s eventually accession to become a formal part of that country.

Some here say that Pakistan’s response is also rooted in the fear that militants the Pakistani security forces once mobilized to fight India in Kashmir are gearing up again right as Pakistan faces the threat of international sanctions if it does not crack down on terrorist groups .

One former Kashmiri militant said he was angry at what he saw as a hypocritical betrayal by Pakistani officials, who recently shut down the border after pushing various militants to cross it in the 1990s.

The militant, who spoke on condition of anonymity out of fear of reprisal by the authorities, said Pakistan’s military had “polluted” the Kashmiri cause by using the issue as a rallying cry for various terrorist groups in Pakistan to fight India, including Lashkar-e-Taiba, which took part in later attacks against India’s parliament in 2001 and in Mumbai in 2008.

“We were freedom fighters, made up from the Kashmiri people. But then Pakistan pushed groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba on our movement. People began to confuse our struggle for freedom with a desire for terrorism,” the former militant said.

Under heavy international pressure to cut links to militants , Pakistan is squeezing the jihadists who once operated freely in Muzaffarabad city, a nerve center for anti-Indian groups, locals say.

In Muzaffarabad, the local office of Hizbul Mujahedeen, a leading faction in the deadly insurgency that wracked Indian-held Kashmir in the 1990s, has been shuttered by officials since May.

“Jihad had once become a way of living,” said Manzoor Gilani, the former chief justice of Azad Jammu and Kashmir.

Now, “not every Tom, Dick and Harry can stand up and say they will go for jihad,” Mr. Gilani added. “The jihadists are now styled as terrorists. They served the interests of Pakistan at one time, but now Pakistan feels it was a bad way of doing business.”

But with India moving unilaterally to finalize its grip on Kashmir, some residents say Pakistan has chosen the worst time to shift gears.

Abdul Rashid Turabi, the former head of Jamaat-e-Islami, believed to be the political arm of the militants Hizbul Mujahedeen, insisted that his group still hoped for peace. “That and dialogue are the priorities,” he said in an interview.

But he added that time was running out for a diplomatic solution to the crisism, and that many here were unwilling to hold back.

“Narendra Modi is driving people to jihad, not me,” he said, referring to India’s prime minister.

Other residents were less restrained.

“The only solution is war,” said Muhammad Arshad Abbasi, a shopkeeper in Chakothi, one of the last border towns before the line of control. “It has been 70 years, and what has talking with India achieved? There is no way other than jihad.”

Zia ur-Rehman contributed reporting from Karachi, Pakistan.

Maria Abi-Habib is a South Asia correspondent for The New York Times. She can be found on Twitter here: @Abihabib

Kashmiris are living a long nightmare of Indian colonialism

Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology, University of Warwick

Disclosure statement

Goldie Osuri does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Warwick provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

India’s decision to revoke the special status of Jammu and Kashmir in early August, and the repression and communications blackout that followed, is another step in India’s long history of colonising Kashmir.

Narendra Modi’s administration effectively annexed Kashmir by abrogating Article 370 of the Indian constitution, adopted in 1954 to guarantee Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status. But this semi-autonomy has been a hollow shell which has allowed India to engage in torture , extrajudicial killings and mass disappearances .

Scholars of Kashmir have called this process a constitutional occupation , and see the repeal of Article 370 as a “ decades-long plan ” to annex Kashmir.

Though not unexpected, the annexation was shocking. At midnight on August 4, ten days before the 73rd anniversary of its independence, India intensified its military grip over the people of Kashmir. It deployed thousands of extra troops in Kashmir, in addition to the half a million already present.

Since then, there has been a widespread communications blackout , with internet, mobiles phones, landlines, television and radio cut. Harsh curfews were imposed on Kashmiris, the local police were disarmed and at least 4,000 people were arrested , including Kashmir’s political leadership and civil society.

Read more: India’s colossal blunder in Kashmir

On August 14, a four-person fact-finding mission to Kashmir collated reports of night raids, abduction of young boys, sexual assault of women, torture, and a lack of access to food and medicine. Kavita Krishnan, a rights activist who was part of the team, stated : “Frankly, it looks like occupied Iraq or occupied Palestine.”

Some restrictions on movement eased on August 19, but Kashmiris remain in a state of siege.

Pursuit of self-determination

Kashmiris have been living with widespread and systematic human rights violations for the past three decades, most recently highlighted in reports by the UN Office of the High Commissioner in 2018 and 2019 . These reports address the situation on both sides of the Pakistani and Indian line of control in Kashmir, though India’s brutalisation of Kashmiris is striking.

While Kashmir is considered an international territorial dispute between Pakistan and India, for Kashmiris their struggle is one of self-determination .

At the Partition of British India in 1947, Kashmir’s independent princely ruler, Maharajah Hari Singh, signed an Instrument of Accession with India. He was under pressure from a Kashmiri rebellion against his unpopular rule, but did not ask his people what they wanted. The accession was based on the promise that Kashmiris would have a plebiscite or referendum to decide their political future.

Between 1948 and 1957, following a war between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, UN resolutions reaffirmed the right of Kashmiris for a free and fair referendum. But they have never been granted one. Now India’s revocation of Article 370 is an attempt to transform Kashmir’s unresolved international status into a domestic issue.

To find out more about the history of Kashmir, listen to episode 3 of India Tomorrow , a special podcast series from The Conversation’s podcast, The Anthill.

Post-colonial colonialism

The case of Kashmir is immensely significant for scholars of colonialism in all its forms. In my own research , I’ve argued that India’s colonialism of Kashmir demands a recalibration of one of the central tenets of these studies: the division of the world into the Europe that colonised, and the non-Europe that was colonised.

This doesn’t mean ignoring the legacy of European colonialism. Major colonialists such as the British, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Dutch and Belgian powers changed the world forever through conquest of territory, slavery and dispossession of non-European peoples. We continue to inhabit a world whose knowledge, political and legal systems are structured by these colonial legacies.

Post-colonial nation-states such as India continue to use British colonial laws to crush any dissent for rights or justice. Modi’s current Hindu nationalist government draws on these laws and extends them as it undermines the rights of tribal people , religious minorities , Dalits and women . The Hindutva, or Hindu nationalist , ideology which Modi’s BJP party espouses was born in the matrix of British colonialism and inspired by European fascism in the early 20th century.

But the case of Kashmir demonstrates India’s own long history of colonialism. India’s latest move also abolished Article 35a of the Jammu and Kashmir state constitution, meaning non-Kashmiris are now allowed to buy land, hold jobs and further colonise Kashmir’s rich resources. As historian Hafsa Kanjwal argues, the influx of Indian settlers is designed to change Kashmir’s demography and may lead to ethnic cleansing, inaugurating India as a settler-colonialist state in Kashmir.

India is already part of an unwritten alliance with other settler-colonial states, such as Israel and the US, based on a destructive arms trade . Both states were created through a history of massacres and violent dispossession of Indigenous and Palestinian peoples.

In explaining its decision to revoke Articles 370 and 35a, India has used the language of counter-terrorism that has become so common since 9/11, coupled with the promise of corporate development . These are two classic colonial justifications reframed for a 21st-century lexicon.

Research and resources about India’s colonial occupation of Kashmir, and Kashmiri resistance to it, are now available at #TheKashmirSyllabus , while updates about the current military blockade are available from the Kashmir Scholars Consultative and Action Network .

The full consequences of the geopolitical tinderbox created by India’s move are still emerging. While the international community urges restraint and bilateral dialogue between India and Pakistan, Kashmir’s right to self-determination must now take centre stage. Kashmiris continue to experience an unbearably suffocating state of siege , and they speak of resistance , come what may.

- Colonialism

- Narendra Modi

- Global perspectives

- Kashmir Valley

- Article 370

Research Fellow – Beyond The Resource Curse

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

The Economic Times daily newspaper is available online now.

Kashmiri youths travelling to pakistan on valid visas sneak back in with terrorists; 17 killed so far.

Recently, the University Grants Commission and the All Indian Council for Technical Education, the higher and technical education regulators of the country, had issued a statement, advising students not to travel to Pakistan for pursuing higher education.

Read More News on

Download The Economic Times News App to get Daily Market Updates & Live Business News.

Subscribe to The Economic Times Prime and read the ET ePaper online.

Will your flight be on time? This should help.

A Supreme Court judgement shines the spotlight on Delhi Metro and Anil Ambani

Is this the opportunity small real estate investors have been waiting for?

Five reasons why metal stocks are hot this April

Dimon says US stock exchanges have too few companies. India has a different problem

Meesho is taking a road less travelled to keep up in its fight with Amazon, Flipkart

Find this comment offensive?

Choose your reason below and click on the Report button. This will alert our moderators to take action

Reason for reporting:

Your Reason has been Reported to the admin.

To post this comment you must

Log In/Connect with:

Fill in your details:

Will be displayed

Will not be displayed

Share this Comment:

Stories you might be interested in

India’s Modi visits Kashmir: How has the region changed since 2019?

Here’s a look at Narendra Modi’s government policies and how they have affected Kashmir since the region’s semi-autonomous status was taken away.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Thursday made his first visit to Kashmir since his government’s controversial 2019 decision to scrap the region’s special semi-autonomous status.

Addressing a crowd at a football stadium in the region’s largest city, Srinagar, Modi claimed that the removal of Article 370, which granted a measure of autonomy to Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir, had ushered in development and peace.

Keep reading

Where ‘love transcends language’: kashmir’s silent village, ahead of election, tension brews in kashmir over tribal caste quotas, kashmir journalist released after five years, rearrested days later, india’s modi visits srinagar, first since kashmir autonomy removed in 2019.

“I am working hard to win your hearts, and my attempt to keep winning your hearts will continue,” Modi said even as the region was placed under a security blanket, with thousands of soldiers and paramilitary forces deployed and new checkpoints set up.

The 2019 decision was hailed by the Hindu nationalist movement that Modi represents, but was met with anger in Kashmir – one of India’s only two Muslim-majority regions – which has seen a decades-long armed rebellion against Indian rule.

Since then, Modi has visited Hindu-majority Jammu region , but has stayed away from Kashmir, until now, on the eve of the 2024 national elections.

Modi and his government have claimed that the scrapping of Article 370, and their subsequent policies in Kashmir, have helped transform the region for the better.

Here’s a look at key changes brought to Kashmir by Modi’s government since 2019:

Special status under Article 370 removed

Article 370 , which was enshrined in India’s constitution signifying Kashmir’s unique relationship with New Delhi, granted the Himalayan region a large measure of autonomy: Kashmir had its own constitution and flag, it could make its own laws in all matters except finance, defence, foreign affairs and communications.

Until 1965, the Indian-administered region had its own prime minister under whom property and domicile laws were passed to protect the interests and territorial rights of the region’s Indigenous people.

However, successive Indian governments watered down the autonomy, leaving the region, in some cases, with fewer powers than other states in India’s federal structure. The region had become heavily militarised after armed rebellion erupted in the late 1980s.

The 2019 revocation of Article 370 resulted in the loss of Kashmir’s flag, criminal code and constitutional guarantees. Several Indian states have laws in place to protect the tribal and Indigenous populations. Kashmir no longer does.

In December 2023, the Indian Supreme Court upheld the 2019 decision. Kashmir has been a major source of conflict between India and its neighbour, Pakistan, for more than 75 years. Both countries claim Kashmir in its entirety but govern only a portion of it.

Indian-administrated Kashmir bifurcated into two

Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir was bifurcated into two regions – Jammu and Kashmir in the west and Ladakh in the east. Neither region has statehood any more, as a consequence of the Modi government’s 2019 decisions.

Both are governed directly from New Delhi.

But people have expressed their grievances against their lack of democratic rights, with Ladakh too seeing frequent protests for more political rights and authority in local governance.

No elections for state legislature

The two new regions – Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh – have been without a state legislature since 2019. The last state elections were held in 2014 – the year Modi first came to power.

In December 2020, the first local elections took place to elect 280 members of District Development Councils (DDC) across Indian-administered Kashmir’s 20 districts. The DDC members, however, do not have the power to amend or introduce laws.

There have also been elections to fill seats in the village councils, also called panchayat, and municipal bodies, but they have very limited power, with the region ruled by New Delhi’s representative and bureaucrats.

India’s Supreme Court in December ordered the government to hold local elections by September 30, 2024.

Kashmir’s pro-India political parties have been demanding that elections be held in the region.

Modi and his government, however, have not indicated when they will hold the elections.

Clampdown on free speech

In the wake of the 2019 decision, New Delhi cracked down on rights activists and local politicians, imposed sweeping restrictions on free speech and shutting down the internet for months. Authorities used “antiterror” laws to arrest Kashmiri activists and journalists.

Human rights groups, including United Nations agencies , have criticised New Delhi for its rights violations in Kashmir.

On Friday, Kashmiri journalist Aasif Sultan was rearrested under an “antiterror” law days after his release from prison after five years. Sultan, the former editor of the now defunct Kashmir Narrator magazine, was arrested in 2018 for “harbouring militants”. His family has denied the allegations.

In November 2021, prominent Kashmiri activist, Khurram Parvez was arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). Kashmiri journalist Irfan Mehraj , who was previously associated with Parvez’s human rights organisation, was also arrested. UN experts and Amnesty International have condemned the arrest of Parvez and called for his release.

Journalist Fahad Shah , the editor of independent news portal Kashmir Walla, was released in November 2023 after more than 600 days of confinement under the “antiterror” law.

Journalist Sajad Gul was arrested in January 2022 under the stringent Public Safety Act (PSA), which allows the detention of an individual without trial for six months.

A global report on internet censorship in 2022 found that Kashmir experienced more internet shutdowns and restrictions than any other region in the world.

Lack of protection for local communities

The Indian government also removed Article 35A of the Indian Constitution, which barred outsiders from permanently settling, buying land and holding local government jobs in the Muslim-majority region.

Other Indian states such as Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand and Odisha continue to safeguard the property rights of local residents, mostly tribal or Indigenous people.

Non-Kashmiris can now buy property in the region. This has prompted fears that the Modi government is trying to engineer a demographic shift in the Muslim-majority region.

These fears were further fuelled by a new domicile law for Indian citizens that the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs introduced in April 2020.

Under the domicile law, those who have lived in the Indian-administered region for 15 years, or have studied for seven years and appeared in secondary or high school-leaving examinations in educational institutions located in the region, are eligible to become permanent residents. Children of government officials who have served for 10 years in the region are also granted domicile status.

This law too has made Kashmiris fearful of permanent settlement by outsiders, including the family members of Indian security forces. Leaders from Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party have rejected that there are attempts to alter the demographics of the region.

Indigenous communities in Kashmir, and Ladakh are also affected by environmental damage and an influx of tourists. Kashmir’s Dal Lake is choked with sewage and its farmers suffer as a result of illegal river mining , and Ladakh is struggling to mitigate flooding and landslides.

Attempt at delimitation in Kashmir

The New Delhi-run local authorities have also redrawn assembly constituencies that many Kashmiris fear are aimed at the democratic marginalisation of Muslims.

A delimitation commission is assigning more legislative seats to the Hindu-majority Jammu region – where the BJP has wide support – than Kashmir Valley, despite the latter having a higher population. The total seats from Jammu region are expected to rise to 43 from 37, but only by one in Kashmir – to 47 from the existing 46, in effect changing the balance of power within the legislature.

Armed attacks continue in Indian-administered Kashmir

Modi’s ruling BJP government has said that Article 370 was abrogated to wipe out “terrorism” in the region and it has claimed that its policies have improved the security of the region.

However, armed attacks have continued in the region, causing deaths among civilians, security forces and rebels. Since 2021, attacks against Indian soldiers in districts like Rajouri and Poonch in the Jammu region have increased.

Ajai Sahni, the executive director of the Institute for Conflict Management in New Delhi told Al Jazeera in December 2023 that most of the recent killings of security forces took place in army-initiated operations. “I don’t believe that normalcy has returned after Article 370 abrogation,” said Sahni.

The South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) reported that the incidence of killing in the Indian-administered Kashmir went from 135 in 2019 to 140 in 2020 and further rose to 153 in 2021. While the number of incidents dropped to 72 in 2023, 33 security forces were killed in the year compared with 30 in 2022, where 151 incidents took place.

clock This article was published more than 4 years ago

Young Kashmiris think India and Pakistan can resolve their differences over Kashmir

Our recent survey suggests they also welcome u.s. diplomatic intervention..

President Trump visited India last week — and it was a trip marked by both spectacle and violence . More than 100,000 people wearing “Namaste, Trump” caps greeted the U.S. president at the world’s largest cricket stadium. But violence erupted in New Delhi over a restrictive new citizenship law , and anti-Trump demonstrations took place in several cities.

So what did Trump say about the situation in Kashmir , which remains largely under lockdown after the Indian government rescinded Kashmir’s autonomous status last August? Trump again offered to help mediate — but described Kashmir as a “ thorn in lot of people’s sides ” and “a big problem between India and Pakistan.”

In India, Hindus, Muslims and police are fighting in the streets. Here’s what’s behind the violence.

India insists that the Kashmir conflict is a bilateral dispute, rejecting third-party intervention . Pakistan’s foreign office spokeswoman, on the other hand, expressed hope that Trump’s recent trip to India would yield “some concrete practical steps” toward U.S. mediation of the conflict.

If President Trump had met with young Kashmiris during his visit, what might he have learned about what they want? Our research suggests that people in Kashmir would have welcomed his efforts to mediate the Kashmir crisis, but also would have pushed to include the Kashmiri people in the process.

How we conducted our research

Between October and December 2019, while Kashmir was in lockdown mode, we surveyed 593 college and university students to study the effects of militarization on political attitudes. We conducted our surveys in Srinagar, Kashmir’s summer capital and most populous city, and surveyed students using the time-space sampling technique at randomly selected locations on university and college campuses and surrounding areas.

Why study the opinions of university students? We wanted to focus on the “ generation of rage ” and the new activism that played a leading role in the 2016-2017 uprisings. At the time, widespread student protests in the Kashmir Valley left hundreds of students injured in clashes with India’s armed forces, and there were many student arrests.

India pulled Jammu and Kashmir’s autonomy. Here’s why that is a big deal for this contested region.

Kashmir’s students remain optimistic

Articles 370 and 35-A of India’s constitution gave Kashmir special protections against Indian immigration and property ownership. The August 2019 revocation of these measures bifurcated Kashmir, which India will now administer as a “ Union Territory .” This means the central government could veto local government decisions. The move to end Kashmir’s autonomy also effectively cut 7 million people in Kashmir off from the outside world — India restored partial Internet access only a few weeks ago.

We conducted our survey at a time when the vast majority of Kashmiris likely felt disaffected and angry toward India. Yet when we asked what it would take to bring long-lasting peace to Kashmir, our survey respondents expressed hope, rather than rage.

Most of the students we surveyed were optimistic about a number of different options. Two-thirds of the respondents believed that peace negotiations between India and Pakistan could be effective. The number skyrocketed to 83 percent when our survey question included the participation of Kashmiri representatives in these negotiations.

Is it worth requesting help from Pakistan? On this question, there was some disagreement. Roughly 64 percent of respondents considered this move potentially effective. A greater share (79 percent) believed that the conflict could be resolved if Western countries considered the Kashmiri people as a legitimate party in the conflict, with a right to have a say in the outcome.

At India’s behest , U.S. policymakers tend to treat the Kashmir conflict as a bilateral issue between India and Pakistan. This narrative deems Pakistan-sponsored terrorism , not Kashmir’s political situation, to be the real cause of unrest in the region.

The Kashmir attack could prompt a crisis in South Asia. Here’s why.

What will resolve the tensions in Kashmir?

Among our survey respondents, the preferred route to resolving the Kashmir conflict was a plebiscite in which Kashmiri people vote to determine the future of their region. Fully 91 percent of our survey respondents were optimistic about this option — with 81 percent deeming this approach very effective.

The plebiscite option has deep historical roots. When India and Pakistan first fought over Kashmir in 1947-1948, after the two countries became independent from the United Kingdom, the United Nations imposed an immediate cease-fire . A subsequent U.N. resolution called on Pakistan to withdraw its troops and India to reduce its forces to a minimum, and asked both countries to “reaffirm their wish that the future status of the State of Jammu and Kashmir shall be determined in accordance with the will of the people.”

Our survey respondents also favored nonviolent resistance to Indian rule. An overwhelming majority (92 percent) considered nonviolent methods effective — but 64 percent considered the continuation of militancy and violence as useful for bringing about long-lasting peace in the region.

Most of our survey respondents want to see a complete withdrawal (91 percent) of Indian troops, or at least a decrease in India’s military presence (92 percent). Kashmir is perhaps the most densely militarized zone in the world. Before the August crackdown, it had roughly one soldier for every 10 civilians .

Is there a way forward?

We asked respondents about three proposals for peace: the “four-point formula,” the National Conference’s “regional autonomy” proposal, and the People’s Democratic Party’s “self-rule” proposal. All three call for the Line of Control, which separates Pakistani- and Indian-controlled territories, to become a porous international border. Where they differ is in the degree to which Kashmir is to gain autonomy and become demilitarized. The four-point plan calls for maximum autonomy and demilitarization, while the self-rule proposal also emphasizes economic integration.

The majority of our survey respondents were optimistic about all three proposals, though the four-point formula was slightly more popular. Under this scenario, the Line of Control would have transit points for people-to-people exchanges, free trade and other economic opportunities. Kashmiris would have special rights to move and trade freely on both sides of the border.

What did we learn from our study of the political views of Kashmir’s younger generation? First, young Kashmiris are open to a variety of approaches to resolving the conflict, from India-Pakistan bilateral negotiations to foreign diplomatic intervention. And a second key takeaway is that despite the crackdown and communications blockade, Kashmir’s young people remain optimistic about the efficacy of peaceful solutions.

Don’t miss anything! Sign up to get TMC’s smart analysis in your inbox, three days a week.

Samir Ahmad is an assistant professor of governance and politics at the Central University of Kashmir. His research focuses on human rights, militarization and India-Pakistan relations.

Yelena Biberman is an assistant professor of political science at Skidmore College, nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and author of “ Gambling with Violence: State Outsourcing of War in Pakistan and India ” (Oxford University Press, 2019). This research was funded by a Skidmore College Faculty Development Grant.

Hafsa Kanjwal is an Assistant Professor of South Asian history at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania, where she has taught courses covering the history of the modern world, South Asian history, and Islam in the modern context. Most recently, Kanjwal authored a book titled “Colonizing Kashmir: State-building under Indian Occupation.” In a conversation with JURIST’s Deputy Managing Editor for Interviews, Pitasanna Shanmugathas, Professor Kanjwal delves into the profound themes explored in her book, focusing on the persistent dynamics of the colonial occupation of Kashmir.

JURIST: Professor Kanjwal, to the readers of JURIST who might be unaware, can you give a brief history of the territory of Kashmir, including how it came to be occupied and bitterly contested by two regional powers — India and Pakistan?

Hafsa Kanjwal: Kashmir has historically been an independent kingdom, and starting in the 16 th century would come to be ruled as a province by the Mughals, Afghans, and Sikh empires. During British colonial rule, the region was sold by the British to the Dogras after the Anglo-Sikh wars. The Dogras, Hindu chiefs from the region of Jammu, had been allied with the British during these wars. The cobbled-together territory that the Dogras obtained or conquered, which included the Kashmir Valley, Jammu, and Ladakh, formed the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir from 1846-1947. As a princely state, the Dogras were Hindu, while over three-quarters of the population was Muslim, many of whom were peasants and artisans that faced high taxation and repression. An anti-Dogra freedom movement emerged in the 1930s and 1940s, parallel to the independence movement in British India. After Partition, the fate of Kashmir remained undecided. A local Muslim uprising in the region of Jammu was quashed brutally by the Dogra Maharaja, in what became known (and erased in history) as the Jammu Massacre. After Pathan Muslims from northwest Pakistan joined their co-religionists in the uprising, the Dogra ruler signed a contentious treaty of accession with the Indian government, which sent its army into Kashmir in late October 1947. India and Pakistan subsequently went to war, and India took the Kashmir issue to the United Nations in 1948. The UN called for a plebiscite to be held in the region (with the options being India or Pakistan), and the region was divided into Indian and Pakistan controlled Kashmir.

Within the part of Kashmir that came under Indian control, the Indian government put in power client regimes that were promised autonomy, or greater self-rule within the Indian union. This was enshrined in Article 370 of the Indian constitution. Yet, India continued to erode the promised autonomy, and denied the people of the region their self-determination. Kashmiris initially resisted through peaceful means to demand a plebiscite, and eventually in the late 1980s regional and international events led to an armed rebellion against Indian rule. This was when Kashmir became immensely militarized (it is still the most militarized region in the world). The Indian army has complete impunity to commit a number of human rights violations such as enforced disappearances, torture, sexual violence, and extrajudicial killings. Daily life under Indian occupation has resulted in immense suffering, and given India’s strategic position in geopolitics and the global economy, Kashmiris have little recourse to the “international community” to have their voices heard.

JURIST: On August 5, 2019, the Indian government unilaterally changed the legal status of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. What did the change in legal status entail, and what was the Indian government’s motive to enact the policy?

Kanjwal: I mentioned in the previous response that the Indian government granted Kashmir’s client regimes autonomy through Article 370 of the Indian constitution in 1949. India was supposed to be responsible for the state’s defense, foreign affairs, and communication, with the Kashmir state government responsible for everything else. Yet, within a few years, India began to violate the restricted mandate and ousted Kashmir’s first prime minister, Sheikh Abdullah, for resisting these moves. Over the years, India has used Presidential Orders to further reduce the region’s autonomy. However, another article — Article 35A — was still largely in place. This allowed permanent residency rights of buying land or property, or gaining state employment, to be restricted to Kashmir state subjects. This was something Kashmir’s earlier client regimes had insisted on in order to protect the region’s demography from an onslaught of Indians.

Hindu nationalists in India have always been unhappy with the kind of “autonomy” that parties like the Indian National Congress have given Kashmir. They have sought to remove Article 370 and fully annex Kashmir. And so, once Prime Minister Narendra Modi was up for reelection in 2019, removing Article 370 was one of his campaign promises, and incredibly popular with his base, given the amount of hyper-nationalist consensus around “claiming Kashmir” in India. With the change in legal status, Indian citizens and corporations can come in, buy land, claim domicile, and settle in Kashmir. The army is able to grab land more easily. Kashmiri Muslims face dispossession of their land and resources, and the threat of being made into a “minority.” Although the settler-colonial framework was evident in Kashmir before the revocation, it became a lot more pronounced since 2019.

JURIST: In what ways has the Indian government’s unilateral action to change the legal status of Jammu and Kashmir affected the lives of Kashmiris, and in what ways has it been stifling democratic voices advocating for self-determination?

Kanjwal: There has always been repression of dissident voices in Kashmir, yet since 2019, this repression has reached new heights. All possible modes of dissent – from journalism to human rights organizations- have been completely, and clinically decimated. India leads the world in internet shutdowns — most of which occur in Kashmir. For decades, journalists in Kashmir played an important role in documenting and sharing the news of what was happening in Kashmir to outside observers. Most of them have either been silenced, arrested, or made into government stenographers. Human rights defenders also have been arrested, and their work has been forced to a standstill. The leaders and workers of the major pro-freedom or resistance political parties have either been killed or detained. The government has taken over academic institutions — no research that challenges state narratives on Kashmir is allowed. Social media cites are widely surveilled so you will rarely see Kashmiris saying or posting anything online; if they do, they will get harassed or removed from their jobs. The Indian government has created a new category called “white collar terrorists” – basically anyone who contests its narrative of sovereignty. Anti-terror legislation is used against any type of expression — from cheering for the Pakistan cricket team to demanding the body of a slain relative. People are scared of losing their livelihoods, so they resort to self-censorship. With the legal changes as well, many live in fear of losing their land or property.

JURIST: The stifling of speech expressing support for the self-determination of Kashmir also seems to extend to the citizens of India. For instance, it was recently announced that critically acclaimed writer Arundhati Roy will likely face prosecution on sedition charges over a speech she made in 2010 where she said Kashmir is not an integral part of India. Your thoughts.

Kanjwal: Kashmir has always been the litmus test of Indian democracy. To speak of Kashmir’s desire for freedom from India is rare, and so it is not surprising to me that the state would want to make an “example” out of those that do, like Arundhati Roy. Before, there may have been others who would speak on Kashmir from a “human rights” angle (which itself is a flawed and restrictive framework) but now, even the space for that has diminished significantly.

JURIST: How have foreign nations, as you assert, made “Kashmir a site of global extraction and environmental destruction” and talk about how all of this is happening through the lens of neoliberalism.

Kanjwal: The removal of Article 370 and 35A has permitted Indian and foreign companies to invest in Kashmir. For example, the United Arab Emirates has signed a series of memorandums of agreement with the Indian government to build shopping complexes and real estate. Israel has made deals with the Indian government to develop agricultural projects (which contribute to the greenwashing of both occupations as well as a move away from indigenous forms of agriculture). Foreign investment ensures that India is going to have supporters as it enacts its settler-colonial project, who will be invested in it then, too.

India has long stolen Kashmir’s natural resources, including water, for its own purposes. Even as Kashmir faces massive electricity scarcity, especially during the cold winter months, India is selling Kashmir’s hydro-electric power to Indian states like Rajasthan. Kashmiris have no rights to determine what happens with their natural resources; Indian colonial rule determines how it gets used and gains the profit from it, too.

Climate experts have long been warning about how Kashmir has a fragile ecology prone to the disastrous effects of climate change and global warming, exacerbated by decades of military occupation. Since 2019, the Indian government has given mining rights to Indian corporations to mine for minerals — including lithium, which was recently “discovered” in the Reasi district of Jammu. These corporations do not adhere to any environmental regulations, and have no knowledge of the local ecology, making the region further vulnerable.

JURIST: Prof. Kanjwal, you have asserted that India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru wanted India to “bind Kashmiris in golden chains” — talk about what Nehru meant by that and how have successive Indian leaders accomplished this goal.

Kanjwal: Nehru is reported to have told this to Sheikh Abdullah, the first prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir. Part of what I examine in my book is how the Indian state and Kashmir’s client regimes saw the Kashmir issue as one that could be won over through development, empowerment, and progress — the “golden chains” Nehru is referring to, or what I call the politics of life. Indian and Kashmiri client leaders felt that if Kashmiris could see for themselves the benefits of Indian rule, they would accept Indian sovereignty. This entailed giving the Kashmir state a lot of benefits and grants that were not given to Indian states. Over the decades, the internal contradictions of this approach became evident, and more brute force or militarization was used to bind Kashmiris. However, even today, we see remnants of the “golden chains” as the Indian state continues to propagate development and progress as part of its settler-colonial rule.

JURIST: India has often cited its control over Kashmir, a Muslim-majority region, as an example of its secularism. Talk about how this notion is problematic and how secularism has been used to entrench Kashmir’s occupation.

Kanjwal: Indian leaders like Nehru basically would say that India’s secular ideals are exemplified through its only Muslim-majority state — Jammu and Kashmir. My book shows how producing a good Kashmiri secular subject was deployed as a mechanism to entrench India’s colonial occupation and criminalize Muslim political aspirations or visions of sovereignty. Kashmiri Muslims were politically useful for India’s “secular politics of inclusion”; but this forcible inclusion is aligned with assimilationist settler-colonial narratives about Kashmir’s history and recent past. The secular was used to both erase and tame Muslim histories of Kashmir. For example, I examine how in film and tourism discourses, Kashmir was presented as a Hindu space and the heart of Indian civilization form the ancient to present times. Kashmir’s Muslim histories or identity were either erased or relegated to stories of “invaders.” Thus, I show how Hindu geographies, imaginaries, and histories were central to these secular discourses, revealing the close relationship between secularism, settler-colonialism, and Hindu majoritarianism.

JURIST: India accuses Pakistan of illegally occupying parts of Kashmir and interfering in its internal affairs. This might be a case of the pot calling the kettle black but to what extent does Pakistan occupy and exercise influence in Kashmir?

Kanjwal: Pakistan’s official state position has always been that it supports the UN resolutions on Kashmir, including the right of the entirety of the J&K princely state (this includes the parts that Pakistan controls) to be able to exercise its self-determination. The issue has always been an international dispute between the two countries, so the language of “internal affairs” really doesn’t apply here.

This is not to say that everything is perfect in the part of Kashmir (Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan) that Pakistan controls, but to draw an equivalence to Indian occupied Kashmir is a fallacy.

Many Kashmiri political formations have sought merger with Pakistan, and so, they have sought Pakistan’s political, military, and diplomatic support. Even the JKLF, a group that seeks Kashmir’s independence, turned to Pakistan for assistance. This is no different from many other anti-colonial struggles around the world, that reach out to states that would be sympathetic to their cause. At times, given the political situation within Pakistan, that support is more forthcoming, while at other times, it is not.

JURIST: Many have suggested that if Kashmir was allowed an independent referendum to determine whether they want to be part of India or Pakistan, Kashmiris would vote overwhelmingly to join Pakistan, and that this is why reason India opposes such a referendum. Do you agree with that characterization of the situation?

Kanjwal: This is certainly why India opposed a referendum in the subsequent years following the UN resolution calling for a plebiscite. However, the Indian government used other reasons to justify their opposition to a referendum, declaring, for example, that Pakistan had not removed its soldiers from Kashmir as part of the UN resolution, or that local elections to the J&K Constituent Assembly in 1951 served as a referendum, and because it had voted to affirm Kashmir’s accession to India, people had accepted Indian rule. With the first justification, both countries were called to remove their troops, but were not able to come to an agreement about the manner and number of troop removal and the authority that would oversee the plebiscite.

With the second, even the UN declared at the time that local elections were not a substitute for a plebiscite. In addition, “local elections” were not actually an exercise in democracy. The 1951 election itself was rigged as the pro-accession National Conference ran unopposed in 73 out of the 75 seats that they “won” at the time. Groups that did not support Kashmir’s accession to India were disqualified from running. This is also why the emphasis on “Pakistan’s troop removal” was a deflection from the Indian government, given that it was already working to entrench Indian rule in Kashmir through its client regimes.

Since then, there have also been political movements in Kashmir seeking a third option — independence — especially from the 1970s and onwards. Given the immense amount of repression in Kashmir today, as well as the decimation of Kashmiri political life, it is difficult to project what would happen in case of a referendum. But, that immense repression itself is a sign that Kashmiris overwhelmingly do not favor India.

JURIST: What would you like readers to take away from your recently released book, Colonizing Kashmir: State-building under Indian Occupation ?

Kanjwal: I hope, first and foremost, that readers will begin to think more critically about the binaries between colonialism and postcolonialism, and also about the decolonial moment. In particular, I hope that readers will see how a formerly colonized nation like India, whose anti-colonial movement is idealized, or which was seen as the leader of the “third world,” can also be colonial. I hope that readers will learn to challenge the narratives that nation-states tell about themselves and their histories. I also hope that they will come to a better understanding of the 5 — not just through violence or dispossession, but also through things that have a positive valence, like democracy, secularism, state-building, and development. I hope they will also come to an understanding of how communities amongst the colonized come to be on a spectrum of resistance and collaboration, and some of the political, economic, or historical reasons for this.

JURIST: What steps do you believe need to be taken so that meaningful pressure, through organized resistance, can be exerted onto superpowers like the United States and the United Kingdom to compel India to end its occupation of Kashmir and support a referendum?

Kanjwal: For the longest time, Kashmiris have tried to appeal to the international community — the United Nations, human rights organizations, and governments in the West. While limited lip service was given to human rights concerns, no meaningful steps were taken to center Kashmiri aspirations, especially as India emerged as an important economic power for many countries.

The Israeli genocide of Gaza in the past few months has revealed, fundamentally, the failures of the Western-led international order. I am not sure what possibility occupied and colonized nations like the Palestinians or the Kashmiris have within this order; in fact, they face further subjugation. I think we need to fundamentally rethink global solidarities and organized resistance, as the movement for Palestine is showing us so clearly in this moment.

The US and the UK will not be able to compel India; they are part and parcel of the subjugation of colonized and occupied peoples. I think pressure can only come from regional actors and regional pressures, as well as continued Kashmiri resistance. It will also be interesting to see what happens within India over the next few years, as the Hindu nationalists continue to impose their vision across the country, including in regions that may not buckle so easily to it. The best that those on the outside can do is to hammer away at the immense soft power that India continues to have by educating themselves and their communities, and take actions whenever possible to reject the narrative of normalcy that India projects. It is also important to identify the people and institutions that are tied to the Indian state project or nationalist narrative where ever you are, and organize against them. Even small symbolic actions make a difference—India certainly gets rattled by it — and can provide solace to a people that feel completely abandoned.

Eichmann trial begins in Israel

On April 11, 1961, the trial of former-Nazi Karl Adolf Eichmann began in Jerusalem, Israel. During the Holocaust, Eichmann was responsible for coordinating the deportation of Jews from Germany and occupied Europe to concentration and extermination camps in Eastern Europe. In 1961, he was captured in Argentina by Israeli commandos and brought to Jerusalem for trial . A panel of three Israel judges found Eichmann guilty on 15 counts, including crimes against humanity, crimes against the Jewish people, and membership in an illegal organization under Israel's Nazi and Nazi Collaborators Law . He was executed by hanging on May 31, 1962. Learn more about the trial of Adolf Eichmann from the Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team.

Lyndon Johnson signed housing rights act

On April 11, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (often refered to as the Fair Housing Act ), an amendment to the landmark 1964 Act prohibiting discrimination based on race, religion or national origin in the sale, rental, financing or advertising of housing. Learn more about Fair Housing Laws and Presidential Executive Orders from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Kashmiris on both sides of the Line of Control and world over will observe the Accession to Pakistan Day tomorrow with a renewed pledge to continue the struggle for Jammu and Kashmir’s liberation from Indian occupation and its complete merger with Pakistan.

It was on 19th July in 1947 that the genuine representatives of the Kashmiris unanimously passed the resolution of Kashmir’s Accession to Pakistan during a meeting of the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference at the residence of Sardar Muhammad Ibrahim Khan in Srinagar.

The historic resolution called for the accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir to Pakistan in view of its religious, geographical, cultural and economic proximity to Pakistan and the aspirations of millions of Kashmiri Muslims.